The Last Guardian is a 2016 single-player adventure game that follows the relationship between an unnamed young boy and a giant gryphon-like creature, referred to as Trico, as they navigate the ruins of an ancient, apparently technologically-advanced civilization.1 The player controls the boy, who is small and weak—he is incapable of fighting the ghostly suits of armor that he and Trico encounter throughout the game, and he often cannot physically traverse the massive, vertical ruins in which the game takes place without falling or stumbling. Meanwhile, Trico, who accompanies the boy, protects him from danger and is essentially impervious to harm; however, Trico is vulnerable to hunger, distraction, fear, and to the lingering effects of traumas it has apparently suffered at the hands of something in the ruins. The boy and Trico, neither fully able to traverse the space they find themselves in, must work together to locate food, overcome obstacles, and defeat enemies.

Critical and audience responses to The Last Guardian were mixed: though the game was praised for its map design, graphics, and for the emotional resonance of the bond between the boy and Trico, many critics took issue with the game’s controls, particularly as they pertain to Trico. Philip Kollar for Polygon writes, “if the main character annoys because he moves exactly as you’d expect a little boy to, then Trico annoys because it acts exactly as you’d expect a cat to act. […] It makes for a realistic depiction of my favorite house pet, but it’s terrible gameplay.”2 Kollar’s criticism encapsulates an issue expressed by many players online: unlike the vast majority of animal companions in video games, Trico does not always respond in the way that one expects or wants, and this is deeply frustrating. This is amplified by the game’s structure, in which the player can often do nothing but call out to Trico and wait for it to understand and follow their commands—sometimes for long stretches of time.

This troubled reception speaks to a broader tension in video games culture with losing control, being patient and accommodating, and having to wait. The Last Guardian exposes and complicates these tensions by framing them in the context of an intimate human-animal relationship. In this essay, rather than pushing these experiences of frustration to the margins by framing them as failures, I argue that the intimate relationship between the boy and Trico could not have come about without those moments of frustration, slowness, and the inability to move properly. Moreover, I believe that the frustration of Trico and the boy’s relationship exposes something crucial about intimacy that prompts a definition of the term that accounts for these negative sensations. The connection between Trico and the boy is drawn through an affective assemblage consisting of the aesthetic, haptic, proprioceptive, and mechanical elements of the game. Drawing from Lauren Berlant, Gilles Deleuze, Felix Guattari and Aubrey Anable, I define intimacy as an affect and read The Last Guardian for the formal and structural ways it renders an intimacy that stems from frustration, waiting and incapacity.

Affect, Relationality, Intimacy

Intimacy, I argue, is an apt framework to understand the pleasure to be found in games in losing control, vulnerability and precarity. Drawing from Deleuze and Guattari, I locate affects “in the midst of things and relations […] and, then, in the complex assemblages that come to compose bodies and worlds simultaneously.”3 I understand intimacy as an affective weight that a relationship—or any relation within the “complex assemblages” Deleuze and Guattari outline—can take on. In the context of video games, this allows us to examine the forces a game world exerts on the player on a formal level—from the aesthetics of the world to the way characters move within it and with each other—as potentially containing intimate affects. I draw from Aubrey Anable’s call in Playing With Feelings: Video Games and Affect to attend to “the unfinished business of representation in theory” by considering aesthetics and representation (particularly animal representation) as significant elements of this assemblage.4 My work departs from Anable’s, however, in that while she criticizes Deleuzian strains of affect theory that “cleave affect from subjectivity” (8) by presenting affect as a network independent from the individual body, I find the relational structure of the assemblage useful as a way to flatten out considerations of representation, aesthetics, mechanics, temporal structure and bodily sensation. It is not any one element that creates the affect of intimacy in The Last Guardian, but the messy and surprising ways they act together.5

So what comprises an intimate affect? Lauren Berlant, in her introduction to “Intimacy: A Special Issue” of Critical Inquiry, draws attention to the tension between the private—communication “with the sparest of signs and gestures,” with “the quality of eloquence and brevity”—and the public—the ideal of “something shared”—at the heart of intimacy.6 Similarly, Nancy Yousef in Romantic Intimacy notes that intimacy “crystallizes a tension between sharing and enclosing as opposed imaginations of relational possibilities,” considering it as referring “to what is closely held and personal and to what is deeply shared with others.”7 Indeed, intimacy seems to be caught in a moment between the private and the public: to intimate is to reveal a closely-held secret. But just as intimacy is connected to revealing, to nakedness, to the baring of secrets, it cannot be fully public, either. Berlant understands that “intimacy builds worlds; it creates spaces and usurps places meant for other kinds of relation.”8 As both authors note, intimacy can take place between strangers, lovers, or family, but within that relation it establishes a private space in which secrets can be revealed. Yousef describes this as “the phenomenal fact of proximity between persons – whether sustained over time, as in a familial relationship, or in the fleeting immediacy of an encounter with a stranger.”9 Intimacy as these authors discuss it can be figured as a space between the public and private, felt as the sensation of closeness or proximity, and of being seen or of revealing.

But this proximity is never certain—in fact, intimacy is defined by a sense of uncertainty. Berlant understands intimacy as deeply connected to desire and fantasy. She considers intimacy as involving “an aspiration for a narrative about something shared, a story about both oneself and others that will turn out in a particular way” and notes that “its potential failure to stabilize closeness always haunts its persistent activity, making the very attachments deemed to buttress ‘a life’ seem in a state of constant if latent vulnerability.”10 “Unstable closeness” seems an apt way to describe intimacy-as-relation: one may aspire for an intimate relation to last indefinitely, or to “turn out in a particular way,” but one can never know for certain what the other will do with that relation, or when they will decide to leave it. The precarity of the intimate thus forces a focus on the present, on the closeness that might disappear, but for now, lingers. This precarious temporality is another intimate sensation.

With all of this in mind, I understand intimate affects in terms of a precarious, synchronous orientation in the present, made pleasurable and terrifying by the sensation of nakedness or revealing of oneself. It is fragile; the threat of embarrassment or humiliation or disappointment lingers at its edges, so much so that it is sometimes more bearable to end the intimate moment than to remain. Intimacy can be cultivated through gestures or sustained proximity, but one can find oneself thrown into intimacy as well.

Intimacy can also take on different affective valences: the intimacy of an unexpected shared moment with a stranger is quite different from the intimacy of a morning spent with an old friend, but both feel intimate. In The Last Guardian, intimacy is formed through frustration, waiting, and the differently-limited capacities of bodies. Frustration and frustrate come from the Latin term frustra, which means “without effect, to no purpose, without cause, uselessly, in vain, [or] for nothing.”11 Frustration is thus connected both to the incapacity to affect things and to a lack of purpose or teleology—to act for nothing is at once to act with no cause and with no effect. Frustration’s relationship to the capacity to affect also evokes Spinoza’s foundational definition of affect as “the modifications of the body whereby the active power of the said body is increased or diminished, aided or constrained, and also the ideas of such modification.”12 Spinoza endeavors to “consider human actions and desires in exactly the same manner, as though I were concerned with lines, planes, and solids,” and so he is deeply concerned in his descriptions with the concrete ways affects alter the capacity of a body to act.13 This definition, though complicated by recent scholarship, is useful as a framework through which to understand frustration. As such, I consider frustration as an encounter with the inability of one’s body to affect other bodies or be affected, a duration that forces one to stay with that inability. It is with these definitions of frustration and intimacy that we can begin to consider the forms of the boy and Trico: if frustration is located in the inability of a body, then we must begin by understanding how exactly Trico’s and the boy’s bodies frustrate, in what ways they are useless.

The Boy: Controllable Helplessness

From the first moments of The Last Guardian, the unnamed boy controlled by the player seems not to fit in in the world of the game. For one, this is manifested aesthetically. In contrast with the dark blues and greens of the cavern in which he wakes up, his clothes are creamy white and orange. While the world around him is thick with the textures of decay—rust, worn stones, moss and grass—the boy’s skin and hair are smooth and glossy. Though the world has already marked him both physically and mentally—he stumbles drearily in his first moments, his body covered in tattoos apparently given to him here—he stands out from it. Even his face seems out of place: while the rest of the world is rendered with a photorealistic aesthetic, his large, round eyes and small nose are reminiscent of Japanese anime. This sense of not fitting in is similarly rendered by the clumsy way the boy moves through the game space: even when he falls only a short distance he crumples to the ground; when he pulls levers or pushes on objects, he can only do so with great difficulty; when he jumps for distant ledges, he is often only barely able to grasp them.

Even when he climbs atop Trico’s back, the beast’s movements startle him, topple him over and yank him around. When he and Trico encounter enemies in the form of possessed suits of armor that guard the ruins, the boy can do little but push at them ineffectually, while they harm him by grabbing him and dragging him towards a door which causes a game over if walked through.14 In their grip, all the player can do is mash buttons on the controller as the boy flails around, which sometimes—though not often—frees him from them before they get to the door. The enemies, in turn, can shoot runes at the boy, which stun and daze him. When he is hurt or waking up from having fainted, the player’s inputs at first only stir his body or cause him to move very slowly; in fact, the boy faints numerous times throughout the game regardless of what the player does. In short, the boy is defined by an extremely limited capacity to affect the world around him.

More colloquially, the website TVTropes—a publicly-editable encyclopedia similar to Wikipedia which organizes popular media in terms of common tropes—describes several moments in the game in terms of “Controllable Helplessness.” The website describes this trope as “a point at which you can be captured or restrained, and not able to move around, but you can still control your character. This might mean being able to wriggle around in your bonds, walk around in your prison cell, what have you, until you either die or are rescued.”15 In one clear example of this, the boy becomes trapped in a round cage. The player can control the boy and roll the cage around an area delimited by impassable ledges, but cannot open the cage or get out of the area until Trico returns over a minute later. The sense of powerless urgency created by this controllable helplessness is amplified by the reason why the boy is in the cage in the first place: he closed himself inside in order to escape another Trico creature who was hunting him and has left for the moment but may return later.

Though TVTropes uses Controllable Helplessness to refer to specific gameplay instances within The Last Guardian, the term is an apt description for the boy’s affects in general. There is almost always only one way to escape a bad situation or one path through a space in which the boy can fit. These paths often involve desperate scrambling over decaying platforms, patient waiting for Trico to understand where to go next, or sheer luck. Occasionally, even when the player and the boy do everything right, the boy may miss a ledge or fail to grasp Trico properly, resulting in a game over as he falls off a cliff to his death. This is perhaps due to sluggish and sometimes unresponsive controls, which itself only amplifies the frustration for the player: the game’s inconsistent controls mirror the boy’s inconsistent helplessness, creating a sense of limited affect for both character and player.

Trico: Uncontrollable Affect

In contrast to the boy’s inability to affect the world around him, Trico is defined by immense affective power that thwarts the promise of purposeful movement. Its stomps, jumps, and leaps invariably destroy the ruins through which it moves with the boy, felling entire structures, creating passages and making others impassable. This goes for the boy as well: though it makes attempts to move without harming the boy, Trico often accidentally knocks him over as it moves past him or approaches him. When Trico jumps with the boy on its back, his body jostles violently around to the extent that even the character model cannot keep up: numerous times when jumping I witnessed the boy’s body spin around in a way that should have broken his arms. That Trico is so powerful as to cause the boy’s body to glitch speaks to its enormous capacity to affect the game world.

Trico’s affects extend even to the camera, which frequently focuses on its movements while often being unable to capture its body in its entirety (Fig 1). In one scene, the boy must coax Trico into a pool of water with food. As the boy looks for the food, the camera gravitates towards Trico’s body above the water as it prepares to jump and finds itself unable to. When Trico finally jumps in, it makes such waves in the pool that the boy is knocked off his feet and into the water, jostling the camera as well. While the boy is defined by his inability to affect the world of the game, Trico is unable to move through the game space without affecting it. Further, its affects are so powerful that they exceed the limitations of the game’s mechanics and camera.

Here, two distinct forms of frustration become clear: first, the frustration rendered by the boy’s inability to affect the world; second, the frustration rendered by the inability of the game system to contain Trico’s affects. This second form of frustration is also created via the boy’s relationship with Trico’s body: indeed, the boy’s interactions with Trico are defined by the constant attempt and ultimate inability to contend with its form.

Trico and Form

The Last Guardian makes one thing immediately clear: its concern with Trico’s form. The game’s opening credits pan and fade over several pen-and-ink drawings of animals from insects, birds of prey, bats, dogs and cats to mythical animals: unicorns, gryphons, dragons and phoenixes. The final image is of Trico itself (Fig. 2).

credits of The Last Guardian. Screenshot by the author.

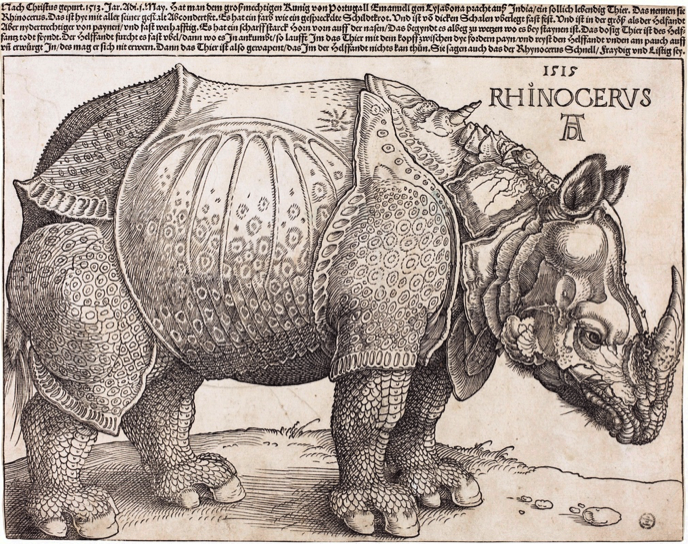

Stylistically, the images evoke a lineage of animal studies drawings that were at once observational and speculative. One reference is the Renaissance artist Albrecht Dürer, famous at his time for his drawings of animals. Dürer’s woodcut drawing The Rhinoceros (Fig. 3), based on an anonymous sketch and second-hand account of a rhinoceros brought to Lisbon from India in 1515, became for Europeans the definitive image of a Rhinoceros until well into the 18th century, despite the fact that Dürer had never seen a rhinoceros before.16 The detailed textures and focus on line lend the image an air of authenticity, but many of these details, like the spiral horn on the rhinoceros’s back and the armoresque quality of its skin, were inaccurate.

The Last Guardian’s opening credits take aesthetic cues. Public domain.

The drawings also evoke the illustrations in the works of Charles Darwin, such as those by T.W. Wood. In a series of drawings for Darwin’s The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, Wood focuses on the bodily and facial expressions of animals in particular emotional states as a complement to Darwin’s observations and discussions of the ways emotions are expressed across species.17

Both referents serve as testaments to the verisimilitude of an animal body through a concern with the specific textures and lines of its form. Further, the introductory sequence begins with images of animals whose forms, gestures and behaviors we find familiar—bees swarming around a nest, a bird preparing to fly, a cat in an aggressive stance—and transitions to increasingly fantastical animals, creating a throughline of behavior and form between animals with which we are familiar and ones upon which we must speculate. For example, by the time we see Trico’s face, we also see in its smooth, long shape and large, dark eyes echoes of the faces of the dog, cat, goat, and gryphon.

This is the first image we see of Trico in the game proper. In this way, we are introduced to Trico’s body as an amalgamation of formal properties that is at once alien and familiar. It is interesting, then, that The Last Guardian’s mechanics center around consideration of Trico’s form and behavior. Climbing to a place out of the boy’s reach, for instance, involves recognizing Trico’s relative height, finding a way to climb its body, and finding a stable vantage point on its back from which to jump off. Other maneuvers require climbing up and down Trico’s long tail, waiting for it to jump up on its hind legs to examine something and then climbing its body, or jumping down onto the safety of its body from great heights. Even the act of climbing Trico itself creates a certain familiarity with the textures of its feathers and fur.

By moving up and down Trico’s body over the course of the game, the player traces out the contours of its form in a way reminiscent of the attention to form in the pen-and-ink drawings: attention to form, empathy and spatial awareness become deeply entangled. Throughout these explorations, the camera is often unable to show Trico’s form in its entirety. The player, through control of the camera, is inculcated in the usually-futile process of trying to fit Trico in to the frame. At the same time, the player attempts to communicate with Trico: the boy pets its fur, calls out to it, and looks up at it. In response, Trico looks back down at the boy and makes eye contact with him; there are many moments throughout the game when the boy and Trico stand still and look at each other, though there is no way for the player to capture this gaze with the camera.

Moments like these encapsulate the intertwining of intimacy and frustration in The Last Guardian: an intimacy defined by a constant, often-futile negotiation, a push-pull that is never resolved but that nonetheless becomes intimate. This intimacy becomes mapped onto space as Trico and the boy struggle to move through the game’s ruined world.

Scale, Verticality, and Progression

The first real introduction to the spatiality of The Last Guardian happens about an hour into the game, when Trico and the boy emerge for the first time from a cave. Trico runs out ahead of the boy into an open area from the mouth of the cave, and in one of the game’s few cutscenes, the camera tilts upwards from behind Trico to reveal a tower so tall that it disappears into the sky. The game cuts to a long shot of Trico, now dwarfed by the incredible verticality of the space and distressed at its inability to fly to the top of the tower. Even when the camera returns to the boy’s control, the tower is so tall that there is no angle from which you can see the top. The ruins the player traverses over the course of the game are similar: they are impossibly tall, too large for either Trico or the boy to traverse; decrepit, and seemingly purposeless, with extended passageways that lead nowhere and infinitely high ceilings.

The Last Guardian is a linear game; there is little exploration involved beyond discovering how to progress to the next area. This is complicated, however, by the way that the space is experienced as linear because of the limited capacity of Trico’s and the boy’s bodies to move through it. This is rendered in a few ways. For one, locations recur throughout the game – the tower Trico and the boy see in the above scene reappears in the distance at several points later on and ultimately becomes their final destination in the game. Other areas, like a long bridge or an open landing area, can be seen in the distance before Trico and the boy get to them. The pair never finds a map of the space, however, and they spend most of the game inside caves or buildings. As a result, the player never becomes familiar enough with the space to understand its topography. Like the camera’s inability to capture the space in its entirety, this adds to the sense of the space being too large and too tall for the pair to comprehend. Along a similar vein, there are some locations to which Trico and the boy physically return; however, invariably they are unable to move through them in the same way as before and must find a different path that wasn’t available the first time around.

This has the effect of giving a glimpse into the potentiality of the space limited by Trico and the boy’s bodies: when circumstances convene (via a collapsed building or fallen rock) so that they can move through the space in different ways, new places open up to them that hint at other paths they are so far unable to follow. On that note, there are a number of pathways throughout the game that Trico and the boy simply can’t follow, either because they are blocked off or because they are too large or too small for the pair to move through. The cutscene at the bottom of the tower at the beginning of the game serves as a microcosm of the space’s logic more generally: a constant reminder of the things Trico and the boy can’t do, the places they can’t go. The result of this is a sense of desperation combined with a hyper-awareness of both the boy’s and Trico’s bodies—the player is constantly made to look at the space in terms of how they might fit (or fail to fit) through it.

At the same time, the differing negative abilities of Trico and the boy to fit through space draws positive attention to distance and scale at several points throughout the game. There are several points when the boy must separate from Trico in order to open a pathway for it to follow him (either by opening a door or destroying a glass eye). Whenever the boy leaves Trico alone, Trico’s howls and whines echo off the walls and cliffs, reminding the player of its absence and of the vast scale of the space. The act of closing the distance after opening these paths is often given particular attention. In one section, the pair must cross a crumbling old wooden bridge that extends down into a chasm so deep it is impossible to see the bottom. With the boy’s guidance, Trico eventually jumps across a gap too wide for the boy to cross. As it lands on the bridge across the gap, the bridge falls down enough that the boy just might be able to make the distance, with Trico waiting on the other side. As he boy jumps, time slows and the sound of the boy’s leap transitions into a processed, almost metallic whoosh, and the camera follows the boy from above as he freefalls towards the chasm. Trico’s head appears from the top of the frame and it catches him in its mouth, and as they make contact, time speeds up again and the whoosh is cut off by Trico’s grunting breaths. As Trico lifts the boy to a safe place on the bridge, he shakes and squirms in its mouth, the player powerless to do anything else until it puts him down. In contrast to the jump, at this moment the game is utterly silent (see press kit video for The Last Guardian from the Internet Game Database below).

This moment and others like it emphasize the tight connection in The Last Guardian between the limitations of Trico’s and the boy’s bodies, vertical space, and temporality. From the exaggerated verticality of the bridge, to the difference in scale between Trico and the boy emphasized by the camera angles, to the slowing of time itself as the boy leaps across the gap, the entire section is anchored around this moment of extended precarity, a moment that emphasizes the boy’s inability to cross the gap on his own.18 This begs the question: if the spatial architecture of the game was designed to create these painfully long moments of precarity—moments which, if the player jumps just a little too early or late, can end in the boy falling to his death—then what relationship does The Last Guardian articulate between frustration and time?

Temporality and Communication: Two Kinds of Waiting

We might divide The Last Guardian into two kinds of long moments. The first is of a type mentioned above: moments of a distance being closed that are bloated by slow motion, exaggerated sound, and vertical space. The second type of moment, which takes up perhaps the majority of the game, is waiting.

Here, I draw from Harold Schweizer’s On Waiting, in which he unpacks the notion of waiting through Henri Bergson’s notion of duration. For Schweizer, while waiting, “the time that is felt and consciously endured seems slow, thick, opaque, unlike the transparent, inconspicuous time in which we accomplish our tasks and meet our appointments;” he describes these moments as perceptions of enduring which, “because they are intimate, are vexingly uncomfortable,” causing the waiter to fidget, pace, complain and consult their watch.19 But waiting also opens up the waiter to the potential to perceive duration, if only for a moment—and “it is in this fleeting moment that the waiter is conscious of her intimate existential duration, of her having lingered in time, of time having lingered in her. Her realization of her duration is as momentary and tenuous as the dreamer’s remembrance of his dream.”20 It is interesting that Schweizer uses the word intimate to refer to these moments of waiting that become encounters with duration. Indeed, the intimate moment as discussed earlier bears significant similarities with Schweizer’s waiting: they are both tenuous and precarious, uncomfortable and sometimes unbearable. Likewise, just as frustration is an encounter with the body’s incapacities, waiting is an encounter with the body’s duration, with the body’s existence in time and therefore its finitude.

As discussed previously, one source of frustration on the part of reviewers and audiences of the game was that Trico doesn’t always listen to the player’s commands. Throughout the game, the player often relies on Trico to jump, climb, walk or stand at particular points in order to access the next area. The player can call out to Trico or use one of several commands, which the boy acts out in exaggerated fashion, to encourage Trico towards certain places. The commands are never precisely defined, but they are mapped to the same buttons that the player uses to control the boy to perform certain actions—namely, to jump, hit, grab and crouch—and to an extent they encourage Trico to respond by doing the same thing. However, the commands are extremely unreliable. Sometimes Trico fails to understand them; sometimes, it appears not to listen or to be reluctant to follow the directive; other times, commands that should encourage Trico to do one thing instead inspire it to do another. In practice, the player and the boy end up waiting for Trico more often than not. Returning to Schweizer, these moments become “slow, thick, opaque,” compelling the player to fidget and pace, to move around so as to occupy the time.21 Several times during my own play experience, frustrated at Trico’s failure to respond to my command, I began cycling through all the commands one after the other, and the sight of the boy haplessly flailing his arms and yelling to Trico became rather comical. Of course, compounding this frustration at waiting for Trico is the frustration of the boy’s body’s inability to act on its own. With the boy’s constant fumbles, falls, and struggles in mind, his exaggerated, ultimately purposeless movement becomes an encapsulation of The Last Guardian’s spatial and temporal frustrations.

These long moments of waiting are punctuated by interactions with Trico that emphasize the boy’s and Trico’s vulnerability. In one scene, Trico and the boy approach a large, glowing room resembling a massive, Trico-sized cage. Trico is extremely reluctant to jump down into the cage from a platform above, and when the boy finally manages to coax it down, Trico is taken over by a mechanical crystalline object in the cage and becomes hostile towards the boy. No matter what the boy does or how long he avoids it, Trico will catch up to him and eat him. Impatience from so much time waiting gives way to total vulnerability, and the familiarity of Trico’s form created through haptic engagement becomes suddenly horrifying as that massive form is leveraged against the boy’s tiny body.

Here, what could be read as payoff to hours of waiting is simply another form of frustration. Like the distance-closing moments described earlier, this frustration is marked by formal intensity that is extended too long, though in this case the extension is created by the player attempting in vain to avoid Trico long enough to survive. Given these structural and formal similarities, we might denote two forms of frustration in The Last Guardian: the frustration of waiting, and the frustration of something awaited happening (Fig. 4).

Intimacy and the Animal

I have written at length about the many frustrations of The Last Guardian, but as of yet we have only seen intimacy come in at the margins. The bloated moments of closing the distance between the boy and Trico were evocative of the intimate sensations described in the introduction to this essay: the precarity of the moment of the jump, the vulnerability to Trico’s actions and to the vertical space, and the present-oriented temporal focus at the moment of contact with Trico’s form all evoke intimacy. But what is intimate about the extended moments of inability described above, or the genuine horror created by the (fulfilled, several times) potential of Trico to eat the boy? Here, I must finally ask a deceptively simple question that, like intimacy, has lingered in the margins of our frustrations until now: how do we define the specific relationship between the boy and Trico?

The key, I argue, lies in the subject position of Trico. The Last Guardian insists on Trico’s subjectivity. So many of its formal details and gestures throughout the game—its careful steps when you’re underfoot so as not to crush you, its anxious glance backwards as you climb tenuously onto its back before a jump, the slight incline of its head as you stand on its back and pet it—draw attention to its capacity to respond to and care for the boy. Even the fact that the player must wait—sometimes for quite a while—for Trico to respond to commands has the effect of forcing the player to accommodate its needs and wants. And the haptic process of learning Trico’s form is also a process of watching its responses – in the long moments it takes to climb up to Trico’s head, with nothing else to do, the player notices Trico’s body reacting to the boy’s movements. When the boy stops to look at Trico, Trico sometimes leans down to get a pat on the head, and in these moments when its face fills the frame, its form is more comprehensible, even if only for a moment.

Collective Incapacities

There is one moment in particular that evokes Trico’s subjectivity to great effect. Towards the end of the game, the pair encounter a second cage apparatus, and once again Trico becomes hostile and eats the boy. When Trico wakes up having regurgitated the boy, who is unconscious beside him, in a long, slow and silent scene, it nudges him, paws at him, picks him up and puts him in the sunlight, and finally drops him in a puddle of water in an attempt to wake him up. The long, drawn-out quality of the scene and the way it opens on a close-up of the boy’s face (reminiscent of earlier scenes in which the boy was awoken by player input) encourage the player to attempt to wake (the boy) up using their game controller, but their input is futile until the boy is finally awoken by the water. Though the player does not control it directly, Trico and the player become aligned in their efforts to awaken the boy, in their similar inabilities to do so and therefore their similar frustrations. In my own play experience I found this moment deeply upsetting. After playing for hours and finding only frustration in the boy’s limited capacity to move, this new frustration of suddenly being unable to move at all expanded into a profound vulnerability that I experienced at once from my own subject position, from the boy’s, and from Trico’s. In light of Trico’s—and at the same time my own—quiet, desperate response to the boy’s unconsciousness, I found an intimacy in our collective incapacities.

Donna Haraway allows us a way forward here in her discussions of companion species and oddkin. In When Species Meet, Donna Haraway uses the term “companion species” not to refer only to companion animals (ie. domesticates), but to denote “less of a category than a pointer to an ongoing ‘becoming with.’”22 Gesturing towards Derrida, Haraway draws from the etymologies of companion species to locate the notion of the companion species in seeing and response. For Haraway, “species interdependence is the name of the worlding game on earth, and that game must be one of response and respect. That is the play of companion species learning to pay attention.”23 Haraway elaborates on this in Staying With The Trouble: Keeping Kin in the Cthulhucene, in which she contends with climate change and environmental destruction by calling for a practice of “learning to stay with the trouble of living and dying in response-ability on a damaged earth.”24 Haraway locates staying with the trouble in “a thick present […] not as a vanishing pivot between awful or edenic pasts and apocalyptic or salvific futures, but as mortal critters entwined in myriad unfinished configurations of places, times, matters, meanings.”25 Finally, “staying with the trouble requires making oddkin; that is, we require each other in unexpected collaborations and combinations, in hot compost piles. We become-with each other or not at all.”26 With the terms “companion species” and “oddkin,” Haraway traces out a model of “being-with” and “becoming-with” marked by a temporality stubbornly and decisively oriented in a present that is thick, slow, difficult and even painful. This is reminiscent of intimacy and frustration: it is in the too-long, too-tall, sometimes unbearable durations of waiting and experiences of inability that make up The Last Guardian where moments of profound vulnerability and intimacy can be found.

The Last Guardian is a deeply intimate, deeply frustrating process of being-with and becoming-with articulated through the troubling companion species relationship between Trico and the boy. It is rare for a game to force its players to stay with the incapacities of their characters’ bodies; so many linear adventure games allow the player to overcome these incapacities by leveling up, acquiring weapons, or gaining the ability to move in new and more efficient ways. The Last Guardian does eventually allow for a new form of movement: at the end of the game, in order to save the boy’s life, Trico spreads its once-injured wings and flies with him in its mouth. It is not a coincidence that this happens just as the game ends, and also just before Trico and the boy part ways: The Last Guardian is not about the promise of powerful movement, but about the intimacy of moving imperfectly. In this essay I attended to the specific temporal and formal structures that this imperfection took in The Last Guardian, and how intimacy in this case became tied to frustration, waiting and incapacity. But what other intimacies might result from games that force their players to be with imperfection, as vulnerable and as intolerable as that can be? Constant failures, precarious encounters and the loss of control are important to the affective experience of many games, and attending to the formal ways that these elements are rendered and contended with might reveal other intimate affects, other ways of staying with the trouble.

- The Last Guardian, Fumito Ueda for SIE Japan Studio, Sony Interactive Entertainment, 2016. In The Last Guardian, “Trico” refers both to the species and to the individual: the opening credits label a drawing of the species as “Trico” along other drawings of animals, mythological and otherwise, labeled with their Latin Binominal nomenclature; additionally, at one point in the game the boy describes another creature of the same species as “another Trico.” ↩

- Philip Kollar, “The Last Guardian Review,” Polygon, December 5, 2016. ↩

- Gregory Seigworth and Melissa Gregg, “Introduction” in The Affect Theory Reader, eds. Gregory Seigworth and Melissa Gregg (Duke University Press, 2009), 6. ↩

- Aubrey Anable, Playing With Feelings: Video Games and Affect, 69. ↩

- Anable, Playing With Feelings, 8. ↩

- Lauren Berlant, “Intimacy: A Special Issue,” Critical Inquiry 24, no. 2 (1998): 281. ↩

- Nancy Yousef, Romantic Intimacy (Stanford University Press, 2013), 15, 16. ↩

- Berlant, “Intimacy,” 282. ↩

- Yousef, Romantic Intimacy, 19. ↩

- Berlant, “Intimacy,” 281. ↩

- Charlton T. Lewis and Charles Short, “Frustra,” in A Latin Dictionary (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1879). ↩

- Baruch Spinoza, The Ethics. Translated by R. H. M. Elwes. (Project Gutenberg, 1883). III. ↩

- Spinoza, III. ↩

- In The Last Guardian, game overs force the player to restart from an earlier checkpoint. ↩

- TVTropes, “Controllable Helplessness.” https://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/ControllableHelplessness. Accessed February 15, 2018. ↩

- Maxime Valsamas, “A Vision in the Forest: Nature Works on Paper by Albrecht Dürer.” In WUSTL Digital Gateway Image Collections & Exhibitions, Washington University in St. Louis. omeka.wustl.edu/omeka/exhibits/show/durernatureworks/animals/rhinoceros. ↩

- See in particular figures 9, Cat, Savage, and Prepared to Fight; 10, Cat in an Affectionate Frame of Mind; and 15, Cat Terrified at a Dog, in The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animal. ↩

- It is interesting to note that it is possible, if the player doesn’t execute the jump correctly, for Trico to fail to catch the boy, resulting in a game over and forcing the player to restart from an earlier checkpoint and attempt the jump again. This serves to extend the precarious moment even longer and accentuates the sensation of frustration and incapacity. ↩

- Harold Schweizer, On Waiting (New York: Routledge, 2008), 16, 18. ↩

- Schweizer, On Waiting, 20. ↩

- Schweizer, On Waiting, 16. ↩

- Donna Haraway, When Species Meet (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007), 17. ↩

- Haraway, When Species Meet, 19. ↩

- Donna Haraway, Staying With The Trouble: Keeping Kin in the Cthulhucene (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016), 2 ↩

- Haraway, Staying With The Trouble, 1. ↩

- Haraway, Staying With The Trouble, 4. ↩