In the Tipton Three Exhibition Space, a projection screen displays “Hung Lazy Boy.”1 Created by artists Carling McManus and Jen Susman, this animated GIF features the eponymous chair dangling in chains in a living room. On repeat, the chair swings near a home entertainment system and threatens—but never manages—to yield to the imperatives of gravity. Because this cryptic sequence is showing at the Guantanamo Bay Museum of Art of History (hereafter referred to as the Museum), its precarious status may prompt associations like the hooded man of Abu Ghraib; practices of bondage, hanging, and lynching; or the recliners in which some Guantanamo detainees consume media or receive force-feedings. It also suggests that Americans cannot shut out their government’s abuses in the fortresses of their comfortable homes.

In the same exhibition space, a 59-minute digital video, “Performing the Terror Playlist” is playing.2 This work by Adam Harms is a found collage of karaoke singers who perform the songs that interrogators blared nonstop for twenty-four hours to physically and psychologically torture detainees.3 The sound quality and tone of the performances vary greatly among the 18 songs in the video—they range from a toddler’s endearing version of the Barney theme song to a group of young men aggressively screaming the lyrics of Rage Against the Machine’s “Do What They Told Ya.”

This assemblage similarly critiques Americans’ use of entertainment to drown out the harsher realities committed in their name.

While the Museum’s contributors use creative techniques to underscore the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base’s harsh realities, it is the Museum that employs the most audacious technique. Its website informs visitors that the facility is closed on Mondays, invites groups to take tours with docents, and provides travel information to its location at the former detention complex in Cuba. The website also explains the Museum’s history by stating, “When the last detention facility in Guantanamo Bay was officially decommissioned in 2010, an international team of artists, curators and architects began planning and designing a museum that would take the place of the detention facility – a little less than two years later, their work became reality.”4

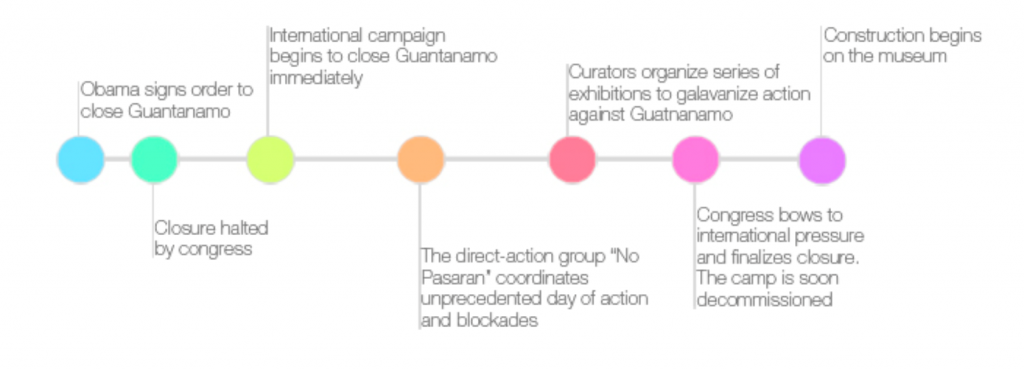

Given these discrepancies with established facts, informed visitors should quickly ascertain that the website’s discursive claim of reality is itself not real. Conversely, as of this writing in February 2017, the detention complex remains in operation with 41 men still held in detention and 26 of those held in ‘indefinite law-of-war detention.’5Despite President Obama’s promise to close Guantanamo and his efforts to minimize its detainee population, political and logistical hurdles forestalled its closure. Since the election of Donald Trump, the prospects for the complex’s closure have grown more remote. During his campaign, Trump stated, “Gitmo, we’re keeping that open. And we’re gonna load it up with a lot of bad dudes out there.”6 He also declared that he was “fine” with prosecuting American citizens charged with terrorism in military courts at Guantanamo.7 Therefore, the website’s alternative chronology, which includes Obama’s 2008 signing of the closure order and the mobilization of global citizens to pressure Congress to follow through in 2010, proves to be an unrealized fiction.

In fact, the Guantanamo Bay Museum of Art and History is not a material space in Cuba, but a virtual site on the Internet. Artist-academic Ian Alan Paul created the Museum as a response to the US military’s system of extralegal indefinite detention (figure 2).8 The website he designed includes pages that describe the fictional history of the detention complex, displays artworks from the aforementioned Tipton Three Exhibition Space, and hosts reading materials in the Jumah al-Dossari Center for Critical Studies. This nomenclature respectively commemorates the men from Tipton, England and Bahrain who were held in Guantanamo for years before their release without charges. In addition to the Museum’s virtual manifestation, which features artists’ and critical theorists’ real work about Guantanamo, the Museum occasionally materializes as a touring exhibition in real galleries.

To work through the Museum’s significations, I will analyze the visitor engagements it offers and its possibilities of meaning production. I will first position the Museum as a work that operates in the tense I call the ‘tactical subjunctive’ and consider its relationship to spectatorship and digital exploration. Because the Museum is a speculative project, I will also engage in a speculative mode that invokes virtual potentialities. Therefore, to ‘visit’ the site, I will tactically deploy the entangled polysemy of the word ‘tour.’ In ways that reflect Guantanamo’s overdetermined complexities, ‘tour’ simultaneously signifies a recreational practice of vacationing sightseers, a period of military duty, and a traveling artist’s set of performances. Furthermore, its French, Middle English, and Latin etymology reveals its relation to the word ‘turn,’ with the French word tour retaining that meaning today.9

Adding another layer to the term ‘tour,’ the Museum website fictionally offers guided tours. This includes a three-day ecological tour that features camping on a hidden beach and the collection of water samples to observe the base’s environmental degradation. The site explains that “[o]n the last day, participants hike back in from the coast with their guide and arrive at the Guantanamo Bay Museum Meeting Facilities in order to reflect upon and discuss their experiences.”10 Thus, like guests employing maps and pamphlets at a physical museum, website visitors can employ the provided images and text as a loose navigational guide or can be more directly led through the descriptions of organized tours.

Ultimately, I will draw on these multiple significations of touring to suggest that the social, physical, and affective events of ‘touring’ can produce a multitude of meaningful ‘turns.’ Whether one travels to observe unfamiliar sights as a leisure activity, a military requirement, or an economic necessity of being a working performer, each pivot of the body and mind generates new vantages to consider. Here, I contemplate my imaginary tour of the Guantanamo Bay Museum of Art and History to argue that such virtual experiences can provide a vital turning point toward the emergence of alternative visions.

Tour Reflections #1: After two connecting flights and nearly eighteen hours in transit, the plane is finally dipping toward the airport. I can see the patchwork of green curves of land and red roofs re-forming through the window. Below is Cuba, or at least the American section of it. I never thought I could see this place firsthand or that it would be demilitarized in my lifetime.

In a description that applies to the Museum, Rita Raley frames tactical media as temporary, open-ended works that aim to disrupt hegemonic ideologies. Rather than operating in terms of an oppositional ‘us vs. them,’ tactical projects both decentralize the artists’ role and reimagine the audience as a plurality of interactive participants that co-constitutes the project’s directions.11 Raley writes, “The audience concept is thus as flexible and ephemeral as the artistic activity itself. Tactical media is performance for which a consumable product is not the primary endgame; it foregrounds the experiential over the physical.”12 Consequently, the legacies of such transitory media are often primarily situated in participants’ memories and altered perspectives.

As the Museum exemplifies, works of tactical media provide a small but not insignificant way for those outside of mainstream channels of power to unsettle hegemonic orders. Aided by the collective efforts of the artist collaborators and the ‘visitors’ who ‘tour’ the Museum, this project’s fictions provide unorthodox understandings of seemingly entrenched terms and problematize apparently unilateral notions. According to Raley, “Tactical media signifies the intervention and disruption of a dominant semiotic regime, the temporary creation of a situation in which signs, messages, and narratives are set into play and critical thinking becomes possible.”13 To extend this idea, the disruption of a dominant semiotic regime is connected to the disruption—however incidental—of a dominant regime of power.

Ian Alan Paul, the Museum’s creator, similarly frames his intentions by noting:

One of the things I hope that the project does is defamiliarize and disrupt the way that we think about the prison, to make it strange and understand it in its contingency: as something that exists but didn’t have to exist, and could no longer exist if we wanted it enough. This kind of process, the process of defamiliarization, is one that is inherently unpredictable. . . . In a way we’re asking questions we don’t have answers for, and this is the enactment of a particular politics. We want to create the conditions for things, rather than enact specific things in themselves.14

By ascribing contingency and unpredictability to the Museum’s production process, Paul recognizes that the experiences the project generates will also be contingent and unpredictable. It is impossible to anticipate how visitors will respond, or imagine how many will opt to take the tour. Yet, rather than delimiting how the participants will navigate the Museum, his work vivifies a multitude of interpretations of Guantanamo Bay.

In this sense, the Museum and similar media operate in the tense I call the ‘tactical subjunctive,’ or a speculative modality that aims to activate virtual potentialities. This tense of the unreal “is used to express situations that are hypothetical or not yet realized and is typically used for what is imagined, hoped for, demanded, or expected.”15 It is associated with desiring, opinion, doubt, and possibility, all of which could apply to the current indefinite state of Guantanamo Bay. In addition, the subjunctive’s appearance causes the expressed verb to undergo a change in conjugation. Through the alteration of the verb form, the tactical subjunctive reflects a small but meaningful shift in the performed action. In the context of the Museum, the tactical subjunctive of the project’s speculative visions may compel some visitors to shift their thinking and newly conceive of taking action. Catalyzed by imaginative sights and sounds, these tourists can rhetorically move from “It’s too bad that this detention facility is still operating” to “We insist this detention facility be shut down.”

Tour Reflections #2: It’s strange to walk up to this space in person after all I’ve read about it. The exterior to Camp No. 5, with its fresh paint and new signage, seems so unremarkable now. I try to imagine the CIA interrogators who tried to break down men on hunger strikes and the gasps of waterboarded detainees. I try to picture the men held in unbearable stress positions and solitary confinement. In the wake of such a fraught legacy, I’m relieved that a museum devoted to art and history has taken the place of the military facility.

Citing the ills of late capitalism and mass media, theorist Jean Baudrillard has decried the contemporary condition of ‘hyperreality,’ or “the generation by models of a real without origin or reality.”16 This state is marked by the proliferation of ‘simulacra,’ which Baudrillard situates in contrast to ‘simulation.’ For him, a simulation is a mediatized representation that attempts to imitate or duplicate the real. Examples of this are a map or impersonation. By contrast, he defines a simulacrum as a more deceptive mediatization that is “never exchanged for the real, but exchanged for itself, in an uninterrupted circuit without reference or circumference.”17

Initially, Baudrillard’s framework suggests that the Museum is a simulation. He states that simulation involves pretending to have what the simulator does not have and is predicated on absence.18 Here, that absence is partly the lack of collective action and the political clout to compel the detention facility’s closure. However, it is also a response to the relative absence of signs from inside the facility that can visualize the impacts of indefinite detention for global publics. With very little access to detainees, the reliance on secret ‘black sites,’ and the use of ‘touchless torture’ to forestall indexical traces of abuse, the Museum simulates a possible future rather than relying on optics and documentary evidence. This absence becomes a structuring force as the Museum highlights the negative spaces of its own construction. Baudrillard further observes that pretending preserves the principle of reality, while simulating blurs the boundaries of truth by partially instantiating the simulated version.19 Thus, visitors who speculatively tour the Museum are blurring the delineations of real and unreal and activating the imagination of more utopian possibilities.

The website as a virtual media object that mediates visitors at every step of their fictional tours also seems to position the Museum as a simulacrum. Baudrillard implicates media in the “mutation of the real into the hyperreal” and correlates the proliferation of mass media with the impossibility of the existence of the real today.20 He also notes that the excessive meanings of audiovisual texts and the pleasures that viewers/visitors take in pretense blind them. This fatalistic perspective, wherein media representations falsely claim a faithful relationship to reality, leads him to assert that truth is “no longer the reflexive truth of the mirror, nor the perspectival truth of the panoptic system and the gaze, but [a] manipulative truth.”21 In this framework, media objects cannot participate in critical resistance, because they are enmeshed in late capitalism. Furthermore, Baudrillard’s opposition between a now-irrecoverable real and current hyperreal reductively totalizes both states and assumes that the earlier real was evident and unmediated.

Conversely, Paul recognizes a power in tactical subjunctive media that employ fictions to enliven the contemplation of possible realities. Such texts seek to galvanize rather than manipulate, or perhaps they manipulate in order to critically reveal more systemic manipulations. Paul states, “It’s not as if there is a real objective and material world opposed to manufactured and/or produced fake ones. Instead, the aim of critical fictions/simulations like the museum is to make clear the ways in which our political and social realities are always produced.”22 Contrary to Baudrillard, this social constructivist understanding of meaning production asserts that Baudrillard’s ‘real’ is merely another hegemonic idea of reality.

I argue that the Museum’s uses of critical simulation and counter-simulation can creatively expose visitors to the state’s broader manipulations. During my own tour, the Museum’s fictional status nudged me to think of the many media fictions and staged performances upon which the invasion of Iraq and the War on Terror were founded. One such spectacle was the Bush administration’s frequent television appearances, during which the figures falsely insisted that the Iraqi regime was stockpiling WMDs in Iraq. Another was George W. Bush’s arrival in a flight suit on an aircraft carrier to presumptuously make his “Mission Accomplished” declaration. More recently, the state’s willful blurring of fact and fiction recalls travesties like Donald Trump’s petulant insistence that he drew the largest inauguration crowd in history. When his press secretary defended the demonstrably false assertion, Trump’s counselor, Kellyanne Conway, dismissed the abundant visual evidence to the contrary in the name of “alternative facts.”23 In these cases, they fictionalized reality to uphold the flimsy premises of dominant ideologies rather than to dismantle hegemonic conceits (figures 4 and 5). 24 25

The Museum’s simulations can also reveal the comparable nature behind Guantanamo Bay. As Elspeth Van Veeren notes, the rigorous regulation of media access and a strategic publicity campaign render the detention complex a simulation. She writes:

Filtered through the ‘triple screen’ of manufactured tour, selected spectator, and mediation, the telegenic spectacle of Guantánamo not only produced a ‘reality’ of Guantánamo, but one that worked to communicate a particular reality of detention and interrogation. In particular, this process succeeded in sterilizing the violence associated with detention. . . . But more importantly, this triple screen also worked to produce a simulation of war, one where the Global War on Terror is necessary and just, and the United States by extension humane and good. Through the everyday repetition of this spectacle . . . this reality of Guantánamo came to dominate.26

Thus, detecting the critical lies that animate the Museum can help visitors recognize the deeper ideological lies of mainstream media and hegemonic discourses. Indeed, Umberto Eco suggests that distinguishing and interpreting falsities are the foundations of interpretative analysis. Eco states that “semiotics is in principle the discipline studying everything which can be used to lie.”27 He also notes that any sign that tells the truth can be used to lie, which demonstrates the urgent need to cultivate an informed, discerning public.

Tour Reflections #3: A small crowd of museum visitors is gathering around McManus and Susman’s projected image, “Hung Lazy Boy.” We mostly keep our distance, as if trying to separate ourselves from its indictment, but a few viewers move closer to the screen. One man, whose silhouette overshadows the dangling recliner, dries his eyes. “I was here,” he says. “When it was still the other place.”

In the 1970s, apparatus theory conservatively envisioned film spectatorship as a unidirectional act. In that framework, the ‘true’ experience of cinema consists of sitting in a dark room and staring at a screen of projected film images. Jean-Louis Baudry has even connected the physical and optical immobilization of viewers to their ideological susceptibility. Somewhat comparable to Baudrillard, he suggests that the fictional reality onscreen seduces and fools viewers. Because they strongly identify with the narrative, these subjects can be manipulated and indoctrinated with dominant meanings. In a totalizing discourse that unintentionally but evocatively foreshadows Guantanamo Bay’s violence of detention, Baudry writes, “Projection and reflection take place in a closed space and those who remain there, whether they know it or not (but they do not) find themselves chained, captured, or captivated.”28

In an attempt to update this now-hoary conception, Francesco Casetti has proposed the notion of ‘assemblage theory.’ He recognizes that cinema is not “a predetermined, closed, and binding structure, but rather an open and flexible set of elements. . . . And it is not the ‘machine’ [of the camera and projector] that determines the cinematic experience; rather, it is the cinematic experience that finds—or even configures—the ‘machine.’”29 This more adaptable conception reflects the enormous adaptability of cinematic spectatorship today, but also acknowledges that dynamic viewing experiences have existed since the advent of film screenings. Indeed, each screening is a performance, wherein the enacted cultural practices and exhibition decisions influence the perceptions of the text. It realizes that film viewers have always enjoyed an assortment of strategies that exceed facile absorption. Among other options, they could walk out, daydream, converse with other filmgoers, or focus on peripheral sights in the theater. Perhaps most importantly, those who do watch the film can also resist the intended ideologies and form oppositional readings. Thus, film viewing can be an act of emancipatory thinking rather than simply tied to capture and captivation.

Though Casetti does not extend assemblage theory to digital media, its application is evident. The Internet is a decentralized, multi-nodal network of networks that enables users to simultaneously engage with a multitude of interfaces and sites. For digitally literate users with reliable online access, it is relatively easy to discover a range of ideas through searches and links. Therefore, even more than the experience of cinema, which only offers one screen and one common text at a time, digital communication is rife with competing meanings and countless permutations of navigation. Because the Internet is an interactive and co-constitutive assemblage, in which users are continually invited to participate, the meanings they encounter and generate throughout their cyber-‘tours’ are never definitive. However, despite these affordances, one risk of digital freedom is that users can reactively cocoon themselves in information that affirms their worldview. As the 2016 U.S. presidential election evinced, users voluntarily or unknowingly restrict themselves to partisan sites and enclose themselves in what Eli Pariser calls ‘filter bubbles.’30 These users are also more prone to circulating misinformation that reinforces their beliefs. This represents a limit to the tactical subjunctive and the power of imaginative, open thinking. Yet, even as algorithms, interface design, and corporate imperatives diminish the range of navigability, the fluidity and rhizomic dynamism of digital media still arguably make this kind of isolated, absorbed navigation more difficult to accomplish.

Curiously, both the principal ideas of apparatus and assemblage theory visibly manifest within Guantanamo media. While I maintain that apparatus theory is a reductive, overly generalized way to discuss spectatorship, it is distressingly applicable to two forms of Guantanamo spectatorship. First, detainees in the now-shuttered Camp 5 who were deemed ‘compliant’ (itself a nebulous and instrumentalized term) were permitted to watch preapproved films and television programs. However, some could only do so while they are under the supervision of a guard and cuffed into a recliner.31 Hence, they were literally immobilized and only shown media that upholds American ideologies. While the detainees could opt out of watching or form oppositional readings, these circumstances sharply constrained their opportunities to express agency.

At a different but related scope, journalists and documentarians are required to undergo a long bureaucratic process to visit Guantanamo. While there, they are escorted through a ‘show tour’ by a supervising official and only permitted to document preapproved sights. For example, they cannot capture the faces of personnel or detainees or record security features. Exhibits of ‘comfort items’ or ‘show cells’ are also overtly staged for visitors to document. Finally, officials scrutinize all photographs and videos and force the deletion of ‘objectionable’ material.32 Through this mechanism of control, only a limited visuality of Guantanamo can emerge to challenge the state narrative. Most prominently, when photographs of arriving detainees outfitted in surgical masks, goggles, shackles, and orange jumpsuits became a locus of critique in 2002, administrators retreated from these techniques. The controversy also prompted the Pentagon to remove these photos from their websites and designate them ‘for official use only.’33 Thus, this apparatus of censorship manages the perceptions of visitors—and by extension, the global public—and restricts alternative visualities (figure 5).34

Figure 5. An iconic 2002 image of arriving Guantanamo detainees

In contrast to these constrictive structures, the Museum invites a diverse variety of engagements. The links and tabs on its website provide some guidance on navigating the information, but there is no predetermined order that visitors must follow. Likewise, the written descriptions about the Museum enhance the project’s visual components, but do not circumscribe possible interpretations. Thus, its open navigability can help catalyze more open-ended thinking and invites exploration. Its frequent invocations of visitors and its “Planning a Visit to the Museum” and “Apply to Be an Artist-in-Residence” sections also solicit an interactive mode. In the case of the “Planning a Website” page, the site states that “admittance to the museum is free to the global public” and “we also are available to help you arrange any special events which you would like to organize on the museum grounds.”35 For the latter invitation, the website promotes “remote residencies” for “artists from around the world” and “encourage[s] artists working in all mediums to apply.”36 Such flexible appeals encourage those touring the site to participate in shaping both the future of the project and the future of the actual facility.

Tour Reflections #4: In one of the memorial rooms, a plaque commemorates the three years of collective global art and activist movements that pressured Congress to shut down the detention facility. Throughout those organized and spontaneous uprisings, I doubted that they would succeed. I thought that the system was too entrenched and that the politicians were too craven to act. But standing here in this haunted site, I’m proud that I finally joined the last wave of protests and occupations.

Tiziana Terranova notes that the Internet’s hyperconnectivity and interactivity enables a ‘cultural politics of information’ to emerge.37 For her, the proliferation of connections, in which messages cycle through countless and uncertain networks of senders and receivers rather than one direct sender and receiver, expands users’ affective engagements with information. Terranova posits that this contemporary politics “involves the opening up of the virtuality of the world by positing not simply different, but radically other codes and channels for expressing and giving expression to an undetermined potential for change.”38 In her conception, which draws on theorists like Henri Bergson, Gilles Deleuze, and Pierre Lévy, the ‘virtual’ signifies the possibility that the extremely improbable can occur. Because the improbable remains possible, no matter how unlikely, it cannot be excluded from consideration. Thus, the perseverance of this small probability requires accounting for volatility, entropy, and unlikely transformations.39

Recalling Raley’s description of tactical media, Terranova points out that the virtual is ephemeral and contingent. She notes, “[U]nlike the probable, the virtual can only irrupt and then recede, leaving only traces behind it, but traces that are virtually able to regenerate a reality gangrened by its reduction to a closed set of possibilities.”40 To this formulation, I would add that the virtual, like the actual, is continually in a process of reinvention. As the virtual remakes the conditions of emergence, the conditions of the virtual responsively shift. Thus, the real and virtual are hyperdynamic and always in an interrelational flux. My experience of touring the Museum as both a virtual space and a tactical subjunctive future bears out this theory. In its description of the three years of collective struggle that forced Congress to acquiesce to Obama’s order, the project acknowledges that the impending closure of the detention facility is, in fact, a highly improbable but not impossible event. In its foregrounding of the mobilized multitudes who work collaboratively through art projects and protests to demand change, it also asserts that the virtual must be multivocal, imaginative, and inclusive of marginal possibilities.

Yet, it is worth remembering that the virtual does not necessarily correlate with the production of ‘positive’ signs and liberatory mindsets. The extremely improbable merely offers access to greater freedom, which foments broadened conditions for emergence. This means that ‘negative’ or regressive ideologies can also emerge, and result in deleterious and manipulative movements. Moreover, the Museum’s abstractions and its choice not to directly explain its intent leave it prone to misinterpretation. As Paul states, “Some of the most surprising reactions are from people who read the project as an anti-Obama statement, or even as a kind of nihilistic satire. I think these readings are failures of the project in the sense that they are collapses of the kinds of spaces of thought that we all hoped the museum would engender.”41 Such readings, along with those visitors who dismiss the project as meaningless or refuse to participate in the tour, are inevitable results of the Museum’s purposeful ambiguity.

Ultimately though, on my tour, I did find the virtual freedoms of navigation, creative co-constitution of meanings, and discovery to be liberating. The Museum offers a clear but labile vision of the future that does not proscribe the ways to achieve this potentiality. In other words, as the real detention complex continues its extralegal operations indefinitely, without providing the semiotic ‘closure’ that concludes a unified text, the Museum provides a virtual closure that opens new paradigms instead of containing them.42 As Paul observes, “If we can just give someone the *concept* of the prison’s closure, then perhaps they can carry that around with them and perhaps it’ll gestate into something else.”43That “something else” could even gestate into the Museum visitors and other coalitions of engaged actors actualizing the closure of the complex and the psychic closure of a national trauma, as improbable as that currently seems. At the very least, the event of imaginarily touring the museum is a powerful tactic for enacting the subjunctive and catalyzing a vital turn toward new speculative visions.

Tour Reflections #5: I close the Museum’s browser tab and shut down my laptop. My virtual tour has come to an end, but the impacts linger. I now ask myself how I can produce creative engagements with Guantanamo Bay to share with others. Through which other methods can I turn attention and pivot perspectives on this issue to extend its imaginaries? How can I participate in a collective movement across media platforms and physical space? What conditions will finally lead us to declare, “We insist that this detention facility be shut down.”

Acknowledgments: The author would like to thank Peter Bloom, Alisa Prince, and Almudena Escobar López for their valuable feedback on earlier drafts of this article.

- Carling McManus and Jen Susman, Hung Lazy Boy, 2012, on display at The Guantanamo Bay Museum of Art and History, accessed Feb. 17, 2017. http://www.guantanamobaymuseum.org/?url=mcmanussusmanwork3. ↩

- Adam Harms, Performing the Torture Playlist, 2012, on display at The Guantanamo Bay Museum of Art and History, accessed Feb. 17, 2017. http://www.guantanamobaymuseum.org/?url=harmswork. ↩

- For more on the use of music as an instrument of torture at Guantanamo, see Suzanne Cusick, “Towards an Acoustemology of Detention in the ‘Global War on Terror,’” in Music, Sound, and Space: Transformations of Public and Private Experience, ed. Georgina Born (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 275-291. ↩

- “The Guantanamo Bay Museum of Art and History,” created in 2012, The Guantanamo Bay Museum of Art and History, accessed Feb. 17, 2017. http://www.guantanamobaymuseum.org/. ↩

- “41 Current Detainees,” last updated February 2017, New York Times, accessed Feb. 17, 2017. http://projects.nytimes.com/guantanamo/detainees/current. ↩

- Paul Lewis, Maria L. La Ganga, Sabrina Siddiqui, and Nicky Woolf, “Donald Trump cements frontrunner status after big win in Nevada,” Guardian, Feb. 24, 2016, accessed Feb. 17, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/feb/23/donald-trump-wins-nevada-caucuses-results. ↩

- Charlie Savage, “Donald Trump “Fine” With Prosecuting U.S. Citizens at Guantánamo,” New York Times, Aug. 12, 2016, accessed Feb. 17, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/13/us/politics/donald-trump-american-citizens-guantanamo.html. ↩

- “Exploring the History of The Guantanamo Bay Museum of Art and History,” created in 2012, The Guantanamo Bay Museum of Art and History, accessed Feb. 17, 2017. ↩

- New Oxford American Dictionary, Second Edition, ed. Erin McKean (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005). ↩

- “Museum” website, italics removed. ↩

- Rita Raley, Tactical Media (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. 2009), 12-13. ↩

- Raley, 13. ↩

- Raley, 22 ↩

- Ian Alan Paul, e-mail interview with Daniel Grinberg, 2015. ↩

- New Oxford American Dictionary. ↩

- Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, trans. Sheila Farla Glaser (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994), 1. ↩

- Baudrillard, 6. ↩

- Baudrillard, 3. ↩

- Baudrillard,3. ↩

- Baudrillard, 30. ↩

- Baudrillard, 29. ↩

- Paul interview. ↩

- Kellyanne Conway, “Kellyanne Conway: Press Secretary Sean Spicer Gave “Alternative Facts,”” interview with Chuck Todd on Meet the Press, YouTube video posted by NBC News, posted Jan. 22, 2017, accessed Feb. 17, 2017. ↩

- National Park Service, 2009. Public domain. ↩

- National Park Service, 2017. Public domain. ↩

- Elspeth Van Veeren, “Guantánamo does not exist: Simulation and the production of the “real” Global War on Terror,” Journal of War and Culture Studies 4.2 (2011): 202. ↩

- Umberto Eco, A Theory of Semiotics (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1979), 7. Italics removed. ↩

- Jean-Louis Baudry, “Ideological Effects of the Basic Cinematographic Apparatus,” trans. Alan Williams. Film Quarterly 26.2 (1974-1975): 44. ↩

- Francesco Casetti, The Lumière Galaxy: Seven Key Words for the Cinema to Come (New York: Columbia University Press, 2015), 69. ↩

- Eli Pariser, The Filter Bubble: How the New Personalized Web is Changing What We Read and How We Think (New York: Penguin, 2011). ↩

- Debi Cornwell, e-mail interview with Daniel Grinberg, 2015. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Van Veeren, 1730-1733. ↩

- Shane T. McCoy, Department of Defense, 2002. Public domain. ↩

- “Planning a Visit to the Museum,” created in 2012, The Guantanamo Bay Museum of Art and History, accessed Feb. 17, 2017. http://guantanamobaymuseum.org/?url=planavisit. ↩

- “Apply to be an Artist-in-Residence,” created in 2012, The Guantanamo Bay Museum of Art and History, accessed Feb. 17, 2017. http://guantanamobaymuseum.org/?url=residency. ↩

- Tiziana Terranova, Network Culture: Politics for the Information Age (London: Pluto Press, 2004), 3. ↩

- Terranova, 26. ↩

- Terranova, 27. ↩

- Terranova, 27. ↩

- Tiziana Terranova, Network Culture: Politics for the Information Age (London: Pluto Press, 2004), 41. ↩

- Daniel Chandler, Semiotics: The Basics, Second Edition (New York and London: Routledge, 2007), 115. ↩

- Paul interview. ↩