Please follow each link to images, videos or sound as they occur because they are integral to the narrative.

They thought they were tasting the future (which for some people

tasted like cardboard and for other people tasted like sugar).

—Alexis Pauline Gumbs1For the Africans who lived through the experience of deportation to

the Americas, confronting the unknown with neither preparation

nor challenge was no doubt petrifying.

—Édouard Glissant2

Accumulation

She was dismayed when she realized that what she wanted to imagine, what she was struggling to bring into being, now seemed beyond her reach. Was it improbable or impossible? What could she dream in a present of imminent environmental catastrophe? How could she sculpt the contours of a future when the future, any future, had been foreclosed?

She read widely and absorbed what she read, which erased the last few misconceptions to which she clung. She thought she had rid her home of plastic only to find that microplastics rained down from the sky. She kept chemicals away from her house and garden while oil refineries in the US spewed cancer-causing benzene into the air and chemical plants created cancer towns. It was people of color and the poor who sickened and died from breathing this toxic air.3

These corporations are killing us and our children.

An activist all her life she had to admit that she was becoming overwhelmed with ecological grief for her planet and its inhabitants, for the loss of ice from the Arctic and Antarctic, for melting glaciers from Greenland to the Himalayas, for burning forests, north and south, for toxic lakes and drinking water, for increasingly acidic warming oceans, inexorably rising, for national parks and monuments opened to mining and drilling, for the loss of life and beauty.4

She dutifully tries to grasp the magnitude of extinction rendered through the accumulation of numbers as if they are the only value or measure of worth that needs to be registered: a million common murres die in less than a year in the Pacific Ocean; three billion birds vanish from North America; a billion animals burn to death in Australia, a figure that does not include bats, insects, frogs or fish? How much are they worth?5

Extinction is calculated and rendered in ever larger abstract aggregates. Numbers that numb and mystify her conceal not only the causes and consequences of the massive loss of life but the agents responsible for climate catastrophe.6 She must not remain blind to the dying and deaf to the cries of pain.

I say we—organizing this work around it. Is this some community we rhizome into fragile connection to a place? Or a total we involved in the activity of the planet? Or an ideal we drawn in the swirls of a poetics?

Who is this intervening they? They that is Other? or they the neighbors? or they who I imagine when I try to speak?

These wes and theys are an evolving.

—Édouard Glissant7

Fighting the temptation to succumb to paralyses she has to remember, recover and reactivate her understanding of the complex interdependency of life on this planet. She knows how urgent it is to see beyond numbers and abstractions. As long as she imagines herself as separate from the creatures that are being eradicated from the earth, she will remain part of the problem. If humanity is to survive humans have to regard themselves not as autonomous individuals but as organisms, organisms intimately tied to and dependent upon other organisms, that their deaths portend our own.8 Where is the outrage?

On her electronic screen she sees a starving polar bear scavenge for food in the garbage dump of an industrial Siberian city, hundreds of kilometers from its Arctic habitat. The video of its plight is prefaced by an advert for Lexus cars.

In the world’s oceans and seas whales are dying from starvation. The ones we see are washed up on shores their digestive systems full with 40 kilograms or more of plastic. Human stuff. How many do we not see? What is the sound of their agony resounding through the oceans and seas before they are beached on shores? How many whales sink to the ocean floor in silent death bewildered that though full they are hungry and can no longer sing?9

She watched Albatross in the Galapagos and her heart soared. Now she mourns the loss of each and every majestic albatross breeding and raising chicks in the Pacific more than 2,000 miles from the nearest continent.10 Not far enough. Not out of the reach of the detritus of the profligate consumer lifestyle of late capitalism. Albatross feed their young human waste. She murders them.

how do you get the illusion of being light and carefree without

actually giving up any of your hard-accumulated stuff?you get a storage unit

and this is what they did. Until the planet was the

perfect reflection of their crowded hearts….there were sick and hungry children who would carry your necessary excess away for a very low fee. and they did a good job so you would use them again. of course sick poor children don’t last long, so they had to be frequently replaced. but by the end, there were more sick children than places to put stuff….

soon everything that was left had a half-life like hysteria. which meant our bodies were like landfills, places where nothing disintegrated but us….

the conditions of our bodies were simply reflections of the conditions of our storage units, and the conditions of our rain forests. and so the landfill actually became an ontology. the ontology.

simply put. every piece of the planet was filled with trash.

our minds notwithstanding. our bodies included.11

In the global north the appetite for the latest, most stylish smart screens and other consumer electronics is insatiable. She feels alienated from the endless culture of replacing and discarding functional items in which she lives. The poetics of relation make her think very carefully about the role of language in the creation of realities so in the OED she looks for the evolution of the word “upgrade.” In the nineteenth century “upgrade” referred to steep terrain, in the nineteen seventies it became associated with economic forecasts, by the 1980s it was chiefly used in relation to computing power. Now “to upgrade” is a descriptor of a way of life. She knows this is not an improvement: upgrading is a sign of an insatiable and unsustainable desire.

[Watch: Exporting Harm: The High-Tech

Trashing of Asia, Basel Action Network, 2013]

Photo by Stuart Isett, via Basel Action Network.

Many affluent people diligently recycle but they do not witness the people who sort through what they have discarded. Affluent nations, the US, Japan, and the EU, have been transporting electronic waste to poor countries. E-waste from the rich, LCD screens, computers, printers, and phones, is dismantled by those who are poor. This work threatens their quality of life: mercury forms a toxin that can damage organs and nervous systems; lead poisons the microorganisms of ecosystems; cadmium from computer batteries has been linked to skeletal deformities in animals; copper poisons soil, water and bodies; the burning of plastic produces toxic fumes that poison the air.12 The multilayered work of Ellen Gallagher reveals how “capitalist promises of equality through consumption are a cruel masquerade.”

Extremes of wealth create impoverishment and this polarization now characterizes and divides nations and the globe. The affluent insist that those they impoverish stay in their place. The rich do not want the poor next door, or in their neighborhoods, or crossing their borders. She is convinced that Democracia en extinción will be the dividend reaped from the endless accumulation of capital and rampant consumption sustained by the voracious appetite for fossil fuels.13

[Look and explore: Democracia en Extinción imagery at YASunidos]

You don’t have to get all the way to human extinction or the collapse of civilization for true nihilism and doomsdayism to flourish…doom works at the margin too, eating away at the infrastructure of things like termites or carpenter bees.

—David Wallace-Wells, The Uninhabitable Earth14

She is petrified.

In the past artists drew upon imaginings of futurity as a force which galvanized action and resulted in profound systemic change in the past. In the face of planetary catastrophe which terrifies her could former dreams could be resurrected, reclaimed, recycled to foment a revolution in thought, in practice, in politics? Within and across the Americas settler colonialism resulted in bleak futures and threats of annihilation for Africans and indigenous peoples: regarded as less than human they were beaten, humiliated, imprisoned, lynched, raped, shot, starved, whipped, bartered as chattel, exploited as units of energy, herded into slave ships, corralled onto reservations, and discarded as waste.

BUT

Unmitigated brutality failed to eradicate visions of futurity, of communal possibility. It was not pessimism that fueled the will to fight, it was not pessimism that encouraged solidarity, it was not pessimism that brought about transformation but rebellion.

She wished African Americans recognized the urgent need for solidarity with those indigenous peoples at the forefront of climate change activism like the thousands from across the Americas who stood with the Standing Rock Sioux protesting the Dakota Access pipeline or the Wet’suwet’en currently leading the rebellion against mining and drilling and laying of pipelines in Canada.15 Of course their fight is also hers.

Flow

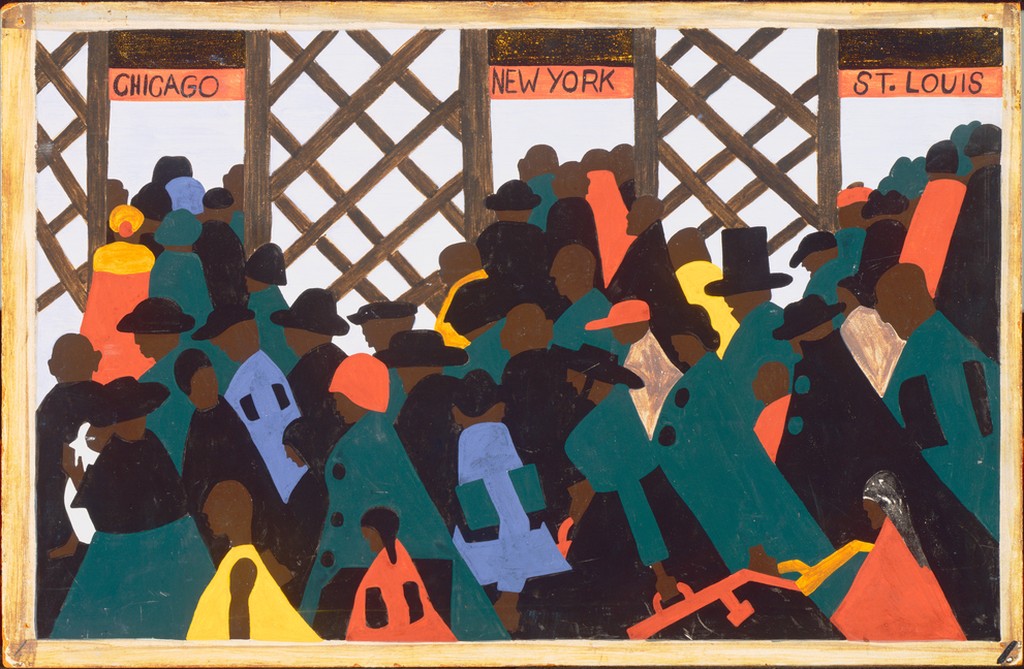

In rich contrasting tones of red, green, blue, and yellow, modulated by deep warm browns, a crowd surges across the canvas. Isosceles triangles of color evoke the hills and valleys of their journeying. Figures topped with hats, dressed up, going places, lean forward. Figures distinct in abstract form but in harmonic movement resonate a common purpose, a shared will and determination. Just one looks back to make sure a child is still close, a child who is the only figure looking down, reluctant or regretful perhaps, evoking what is being left behind not what is to come. In the background the figures have turned. Movement ceases, no more tilted angularity but upright stasis, monuments in half oval blocks of color between openings in latticed fencing: gateways to Chicago, New York, St Louis. In serried ranks they turn their backs to the viewer and wait, solid, defiant, looking toward the future, to blue skies. It is as if they could stand there forever and in the painting they do.

[Watch and listen: Jacob Lawrence on Panel 1 of the Migration Series]

[Explore: Jacob Lawrence, The Migration Series at The Phillips Collection]

The past may be behind but it is not over, history has not ended because black people continue to inhabit the vexatious realm of the unfinished project of freedom.16 In literature, art, and music, peoples of the black diaspora have mined the past in search of stories that have enable them to survive, to navigate past/present/future.

Artists Rights Society (ARS).

Moving north, a trickle became an unstoppable flow—they picked themselves up, took what they could carry and walked away from that unforgiving land. They moved north then. Can their descendants act in solidarity with the poor and dispossessed who continue to move north now, because their lives are accounted of no value?17

Propelled by a search for the future, for there was no future behind them they came and kept on coming.

The future was not yet reflected in our faces. What was to become etched itself gradually into skin, shaped bodies, sculpted bones, molded flesh through unremitting labor, hardship, hope loss and disappointment.

They flowed into cities: cities to which some came for the first time but to which others returned, only to find that they were no longer welcome. They left colonies, fields and plantations: they left the South. There was no future where they came from, just a past/present of toil, poverty and oppression so they crossed oceans.

The current response of the United States to migrants escaping precarious lives, oppression, poverty, war, and starvation is to build over 1.000 kilometers of border walls.

Image courtesy Flickr user Russ McSpadden.

The response of fortress Europe is to leave migrants who cross the Mediterranean in small boats to drown at a staggering rate of death.18

How to represent a global scenario of these voyages? How to comprehend the restless movement and relentless propulsion of these crossings?

[Look and listen: Issac Julien, Western Union Small Boats (The Leopard)

and Isaac Julien, artist talk and projection for Everson Museum.]

In the past they nurtured their dreams. Their children and their children’s children labored to reshape the past/present of parents and grandparents, molding and honing, dreaming possible and impossible futures with shining eyes. Now, children dreaming impossible dreams look out at her from cages. The United States detained 69,550 children in 2019.19

If she has learnt anything from black history it is that instead of indulging in the passive form of citizenship offered by Facebook an active citizenship can only be recovered through civil disobedience, gathering at borders, confronting border patrol agents, dismantling barriers, opening the doors of cages and helping the migrants across.

Impossible Stories

The Sea is History

Where are your monuments, your battles, martyrs?

Where is your tribal memory? Sirs,

In that grey vault. The sea

has locked them up. The sea is History.

Then came from the plucked wires

of sunlight on the sea floor

the plangent harps of the Babylonian bondage

as the white cowries clustered like manacles

on the drowned women

and those were the ivory bracelets

of the Song of Solomon,

but the ocean kept turning blank pages

looking for History.

—Derek Walcott20

She knows that in her daily struggle to stay afloat, it is easy to become dislodged, displaced, submerged, under-water, to remain aware that there even is something you can call a future. In Detroit musicians called Drexciya created alternative realities worlds “intended to be very different from the life that people saw outside of their door, everyday”: futuristic techno rhythms, “music to help people keep going.”21

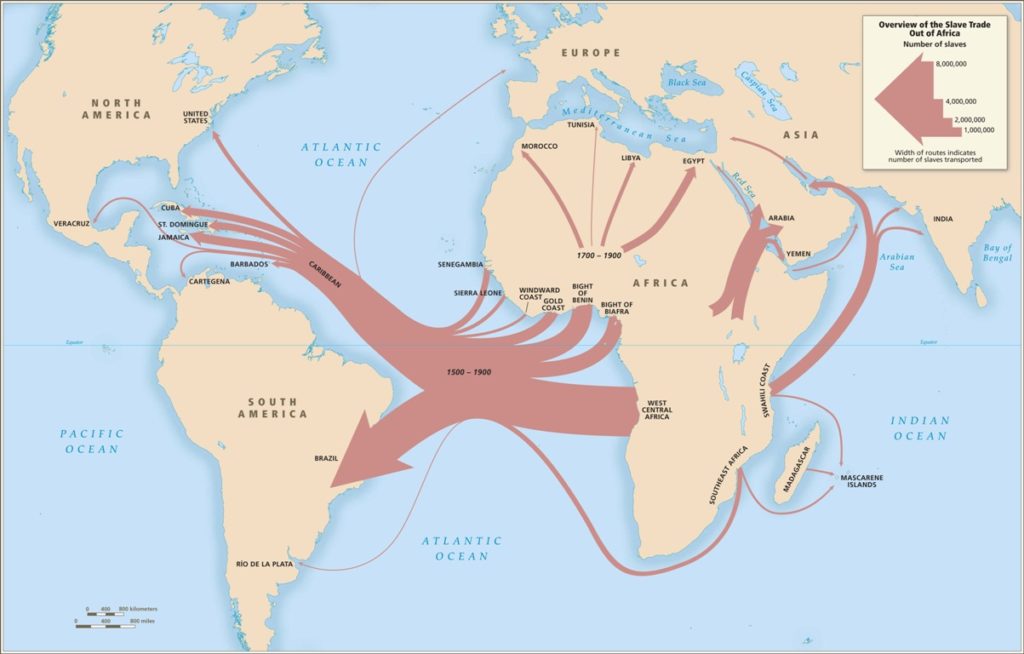

The liner notes of their ’97 CD, The Quest, conjured an origin story for the Drexciyans:22

Could it be possible for humans to breathe underwater? A fetus in its mother’s womb is certainly alive in an aquatic environment.

During the greatest Holocaust the world has ever known, pregnant America-bound African slaves were thrown overboard by the thousands during labor for being sick and disruptive cargo. Is it possible that they could have given birth at sea to babies that never needed air?

Recent experiments have shown mice able to breathe liquid oxygen. Even more shocking and conclusive was a recent instance of a premature human infant saved from certain death by breathing liquid oxygen through its underdeveloped lungs.

These facts combined with reported sightings of gill men and swamp monsters in the coastal swamps of southeastern United States make the slave trade theory startlingly feasible.

Are Drexciyans water-breathing, aquatically mutated descendants of those unfortunate victims of human greed? Have they been spared by God to teach us or terrorize us? Did they migrate from the Gulf of Mexico to the Mississippi river basin and on to the Great Lakes of Michigan?

Do they walk among us? Are they more advanced than us and why do they make their strange music?What is their quest?

These are many of the questions that you don’t know and never will.

The end of one thing… and the beginning of another.

Out – The Unknown Writer23

The question of gender matters to her. Gender is always at stake in any representation of futurity. She is troubled that Drexciya is not concerned with the pregnant women who were thrown overboard their only subject is the liquid-breathing issue from their wombs. Is that her proscribed role in black rebellion to provide a womb for an ascendant black patriarchy exercising control over black female reproduction?24 To her this feels like a return to pre- and post-emancipation anxieties when securing control over women was a political sign of the entry of black men into modernity and equal citizenship.

In Drexciya’s origin fiction the pregnant enslaved women had been jettisoned not merely as waste but as toxic assets by white traders and were, therefore, available to be imagined as the vessels from which a phallocentric and militarized black patriarchy emerged emancipated. She refuses to surrender reproductive control to any patriarchal vision of rebellion and instead looks to the work of black female creative artists for alternative imaginings of futurity and sexual and libidinal politics of reproduction.

© Ellen Gallagher. Courtesy Gagosian.

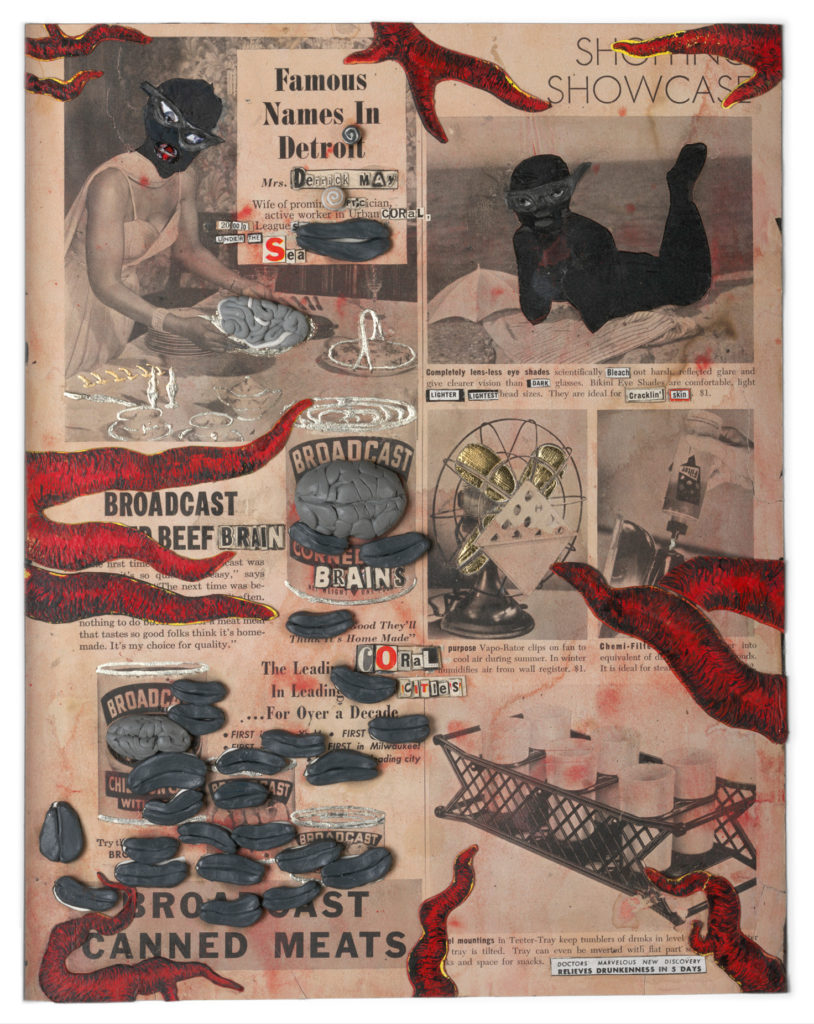

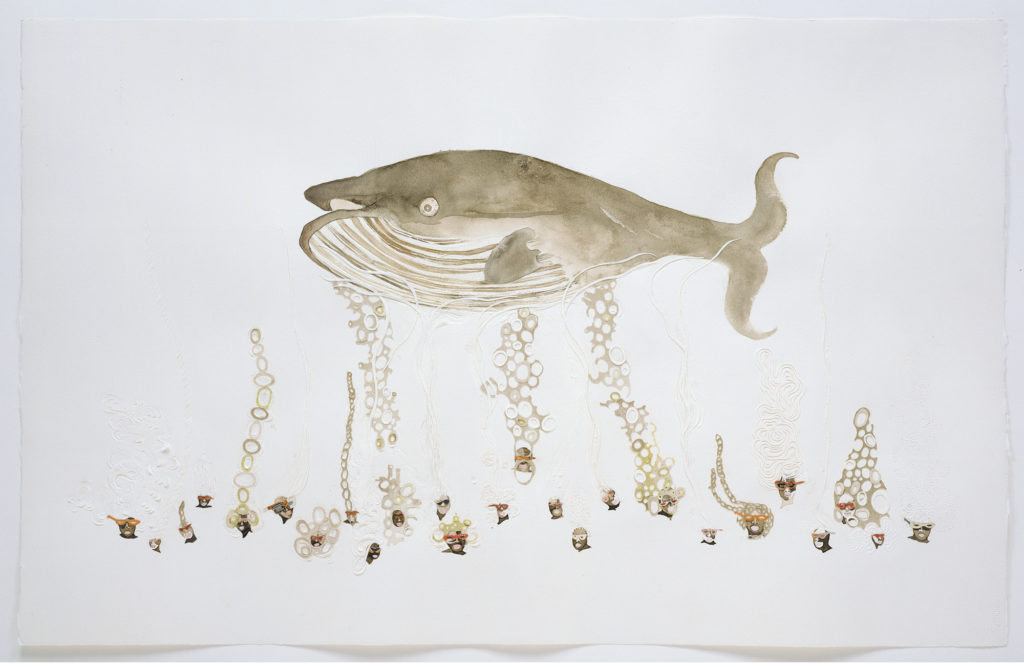

Ellen Gallagher’s practice and process incorporates a multilayering of history into her artworks. Some are built upon archival material glimpsed through slices, or cuts, or through the holes or around the edges of plasticine. In others, archival printed matter will be embedded into watercolor paper. Gallagher makes her viewer penetrate beneath surface appearances.25

Excavating archives of the future in the past is a work of labor (and of love). Laboring as Gallagher does: penetrating beneath the surface digging deep and building up, layer by layer, accumulating meaning; accounting for how inventive we were; how we explored new ways of being and becoming, created new ways of seeing while always protecting our eyes from seeing too much and, of course, always avoiding being seen as we did not want to be seen, sheltering our inner selves.

© Ellen Gallagher. Courtesy Gagosian.

She thinks critics are mistaken to link Ellen Gallagher too closely with the Drexcyia mythology. Gallagher creates complex underwater worlds of marine species and vegetation in which drowned or drowning humans are but one of many multiple selves, diverse bodies and organisms. The Watery Ecstatic series of drawings, paintings and films are oceanographic, concerned with both the physical and biological properties and phenomena of the sea, and imaginaries vast with the possibility of transformation.26 For these drawings and paintings Gallagher carved and scratched into thick paper opening multiple layers of pastness and becoming through figuration and abstraction. In Bird in Hand, 2006, multiple layers of penmanship paper, plasticine, rock crystals, and paints abstract shapes and striations reveal layers of historical and mythological reference.

Some of the layered areas are up to twenty sheets thick, and, cut from differently coloured pieces of paper, their edges reveal striations of color. The upper layers show maps, newspaper cuttings and advertisements, particularly for beauty products, such as wigs and skin treatments, aimed at black consumers.27

A haunting inscrutable world of many interrelated organisms among which the human is only one. Dwelling with Gallaher’s work enables her to find multiple possibilities of knowing and becoming a step toward broadening allegiance and affiliation to all life on the planet.

[S]elfhood is not limited just to animals with brains. Plants are also selves. Nor is it coterminous with a physically bounded organism. That is, selfhood can be distributed over bodies (a seminar, a crowd, or an ant colony can act of a self) or it can be one of many other selves within a body (individual cells have a kind of minimal selfhood.)

Self is both the origin and the product of an interpretive process…. A self does not stand outside the semiotic dynamic as “Nature,” evolution, watchmaker, homuncular vital spirit, or (human) observer. Rather, selfhood emerges from within this semiotic dynamic as the outcome of a process that produces a new sign that interprets a prior one. It is for this reason that it is appropriate to consider nonhuman organisms as selves and biotic life as a sign process, albeit one that is often highly embodied and nonsymbolic.

—Eduardo Kohn28

How do we imagine futures from the literal and metaphoric offspring of violence, “hatred and contempt,” about which the archive is silent? Good question. As Saidiya Hartman has asked, “what do stories afford anyway? A way of living in the world in the aftermath of catastrophe and devastation? A home in the world for the mutilated and violated self? For whom – for us or for them?”29 Familiar with living in the aftermath, she wants to know how to face the emerging catastrophe.

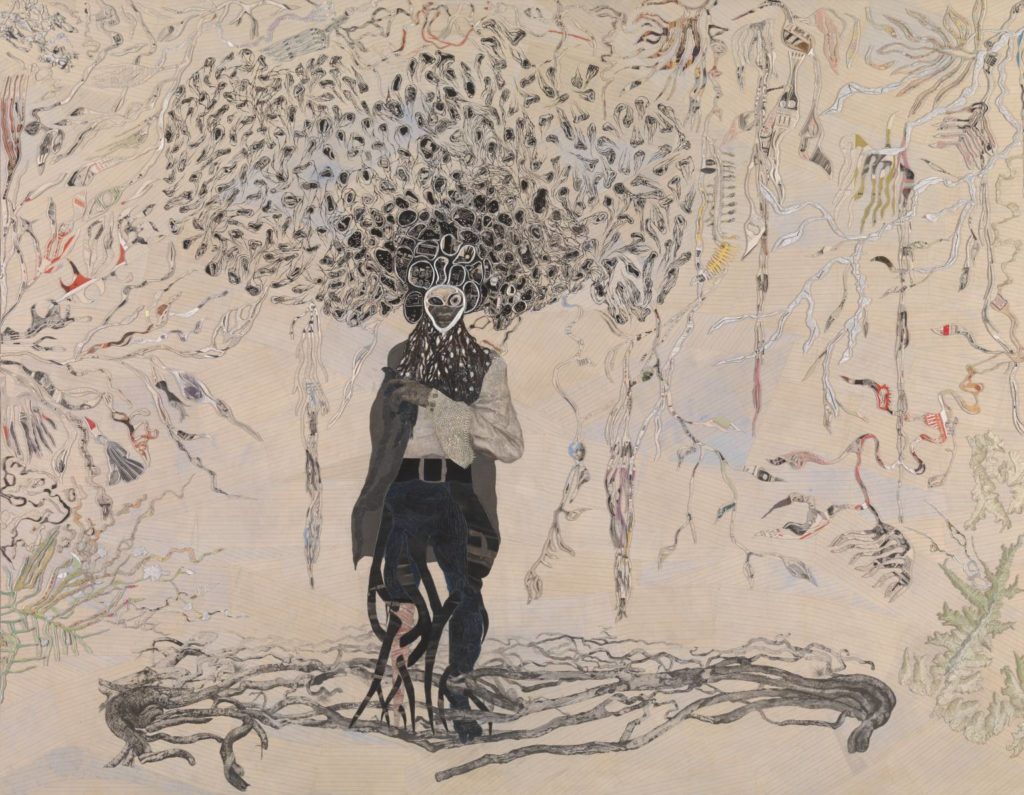

The dramatic and large-scale collages of Wangechi Mutu also bring the archival to the surface. Mutu confronts and scrutinizes globalization by combining found materials, magazine cutouts, sculpture, and painted imagery. Sampling such diverse sources as African traditions, international politics, the fashion industry, pornography, and science fiction, Mutu’s work explores gender, race, war, colonialism, global consumption, and challenges the exoticization of the black female body.30

[Look: Wangechi Mutu, A Fantastic Journey,

exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum 2013-2014]

She wants to draw upon the work of black women, artists, critics, historians, and feminists to inhabit, teach, write and think in the dangerous territory of impossible stories, and in particular, “the writing forward of unfinished stories perceived as history,” stories which appear to be about the past but determine the parameters within which our future can be imagined. Stephan Palmié has argued that “Western historians have constructed their claims on the past on the basis of conceptions of a linear and irreversible growth of unbridgeable temporal distance between past and present realities.” Even though we have the evidence that “the modern world capitalist system was erected…on the unmarked graves of African slaves whose lives were systematically wasted in the service of …primitive accumulation,” the evidence remains an abstracted knowledge of atrocities.31 Their lives, their existences escape our knowing. Or, as Edouard Glissant declared in his Poetics of Relation: “The only thing written on slave ships was the account book listing the exchange value of slaves.”32

When planters looked to ‘increase,‘ they crafted real and imagined legacies. In the absence of living slave children, their own children still inherited the promise of future wealth. Slaveowners whose prospects might have seemed somewhat bleak looked to black women’s bodies in search of a promising future for their own progeny…. and a greater certainty of a future in and for the colony…. a planter could imagine that a handful of fertile African women might turn his modest holdings into a substantial legacy. Black women’s bodies became the vessels in which slaveowners manifested their hopes for the future; they were, in effect, conduits of stability and wealth to the white community.33

In a close examination of the account books and wills of owners of the enslaved, Jennifer Morgan, has revealed how black women’s wombs, were “the vessels” for the manifestation of hopes and “the conduits of stability and wealth to the white community.” The future of their reproductive capacity underwrote the financial system of enslavement and secured the future wealth that the system produced. She wonders if the influence of plantation still needs to be contested?

Plantation Remains

Kara Walker has made radical interventions into the representation of black female bodies within modernity and rigorously contested its promise of a future of progress.

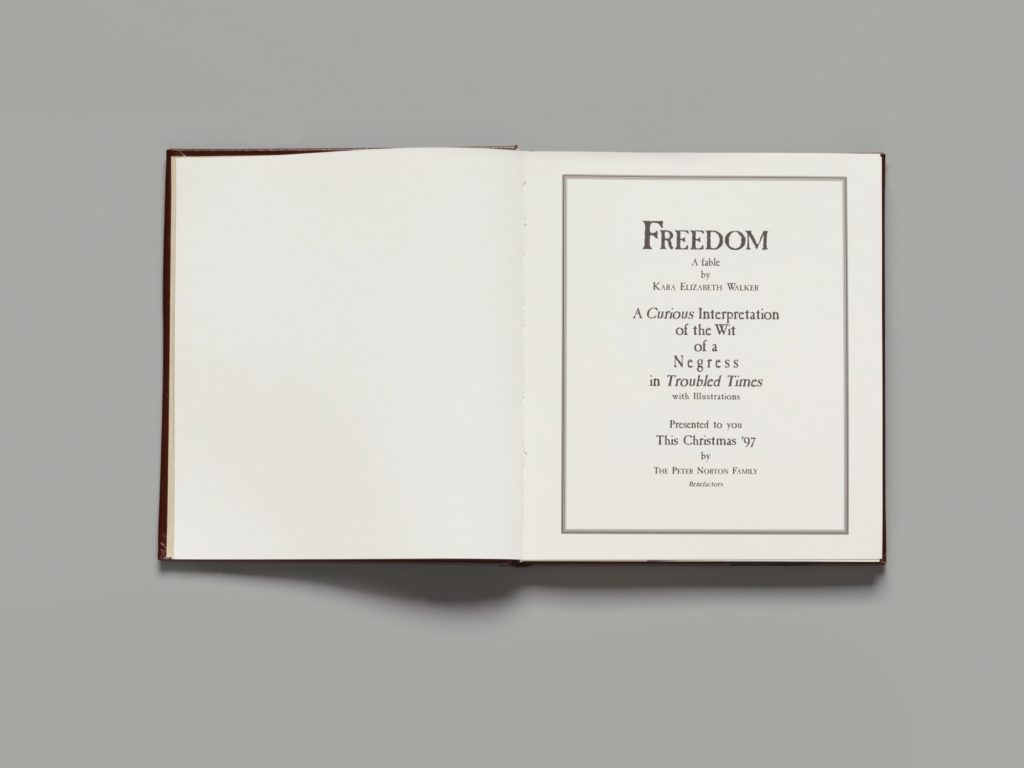

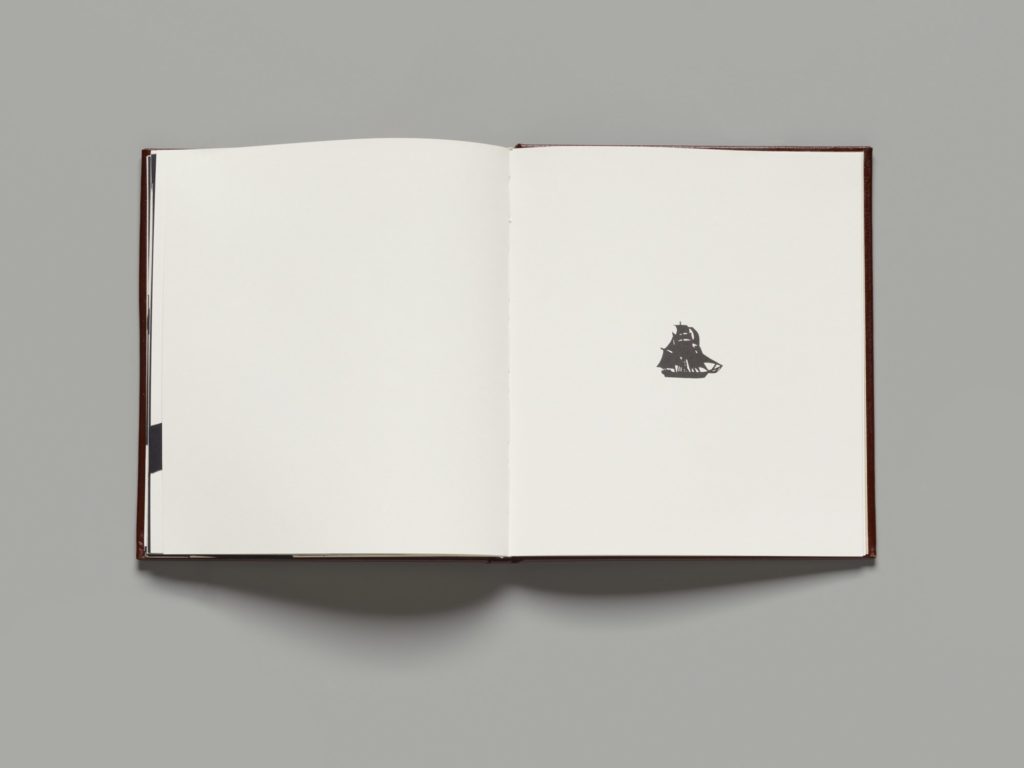

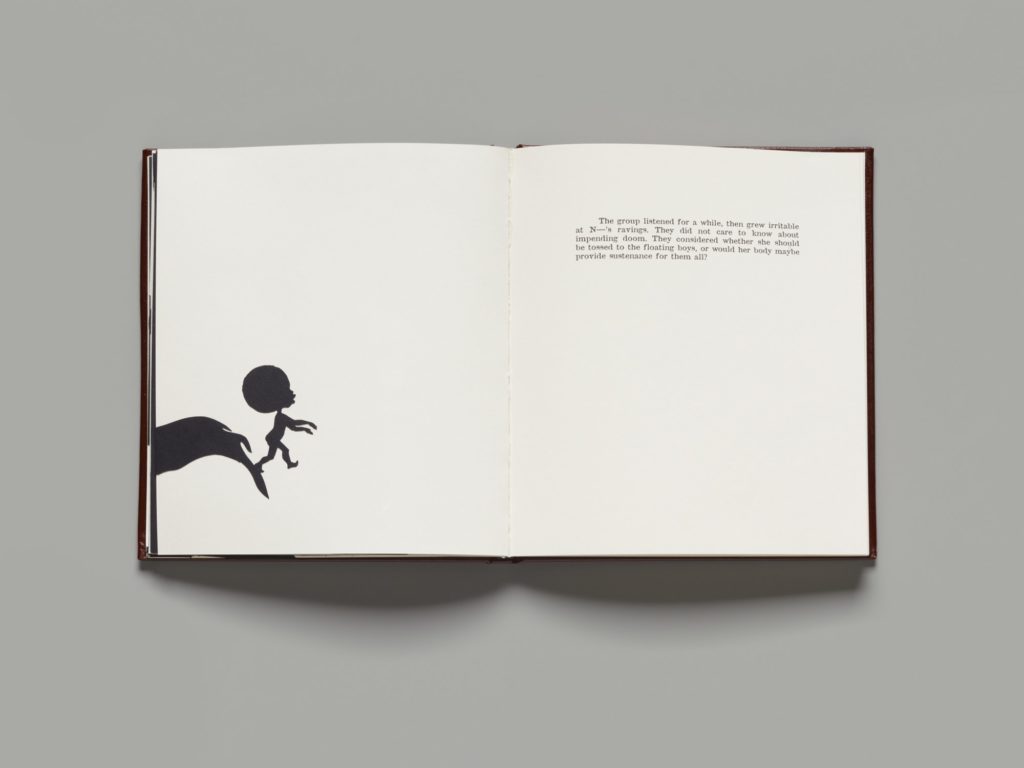

Every Christmas friends of Peter Norton, software engineer and art collector, receive his annual Christmas gift of a work of art. In December 1997, he circulated a pop-up book created by Kara Walker entitled Freedom: A Fable. In 1997, when Walker had previously been exhibiting very large silhouettes on the walls of art galleries, the reduction of the form to the envelopment of silhouettes that both move within and are confined by a book bound in red leather only increases the intensity of their effect.

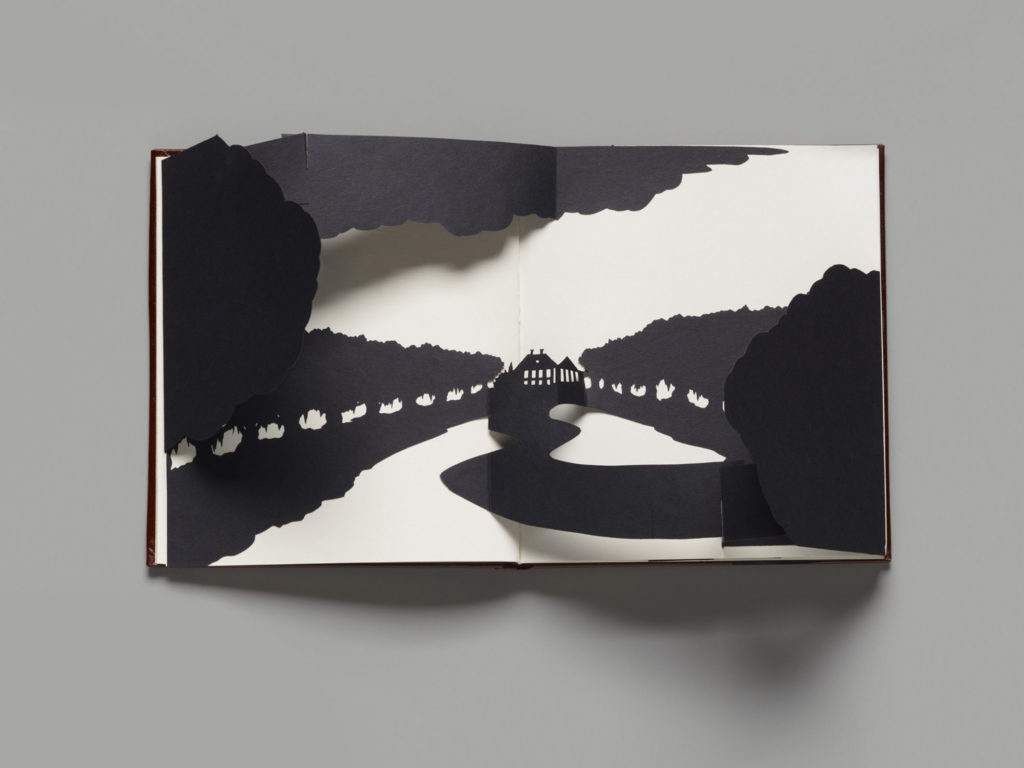

The protagonist, a character more accurately described as a fabulator, is a “soon to be emancipated 19th century Negress, “N,” and the book is her vision of the future. Set immediately after Emancipation, freedom, is not achieved within its pages, rather it is the object of philosophic and political thought and meditation. The artwork is an exploration of a future, a future that is promised, a future in which those promises are forever withheld. The first sentence of the book, “The future vision of a soon-to-be-emancipated 19th century Negress…” is incomplete, it is interrupted by the first silhouette, an image of one of most enduring and stable mythologies in the United States. The pop-up opens through black paper trees to the silhouette of a vista, a tree-lined avenue and a meandering path leading upwards and receding in perspective to a plantation house with tall windows and two chimneys. Is it past, is it history, will it always remain in memory, or as the pages open and it rises does it signal that it is always here in the present?

Is it analogous to another grand house, a house of dreams with tall windows and chimney, the Philip Corbin house on Oak Bluffs, the summer “cottage” of the author’s benefactor, Philip Norton?

Image courtesy Flickr user Gregg Squeglia.

She closes the pop-up of the plantation house and turns the page and is returned, abruptly and unexpectedly, into the middle of the incomplete opening sentence, “involves Africa to an absurd degree,” a phrase which concludes the opening words of the book, “The future vision of a soon-to-be-emancipated 19th century Negress…” words which by now she had forgotten.

…involves Africa to an absurd degree. Liberia, which sounds remotely like a disease or a bit of the genitalia, is the future home full of noble savages living in high-rise straw huts…. Master says… that’s where the Yankee wants to send you after all! “Back to Africa” and away from me. Away from where you are needed most. He conceals his sadness and beats her severely. Screaming, he picks up the closest object in the room – a ladle – and flings it against her brown now bruised temple. Does she flinch? Never, just continues to dream of a land where brown skin means nothing

Later, back in her room in the attic above the kitchen, she nurses her wound and continues with this thought, “If in Africa, everyone is of the same or similar complexion, and this biracial opposition is non-existent, as we know it here…” She trails off. “Well, if there brown skin means nothing, that one’s person can be judged solely on the content of one’s character (words to be repeated, no less urgently some 100 years later, unbeknownst to her, our heroine) then here this skin of mine with me in it must mean everything!”

And this is when she concluded it her duty to become a god.When the war was over…. N — found herself “in the holding compartment of a dank and too old ship, she and about forty others, contraband of war.” A few men, too old and tired to take the place of Adam, a few motherless children, sexless in their burlap four sacks, a few yellow girls of a slightly better caste with crinkly uncovered hair and two boys, twins, named respectively Hannibal and Cane, aged about twelve. These she decided to take into her custody, seeking to rewrite history (as she knew it) in one fell swoop.

N’s journey is supposed to be a journey of repatriation to the continent of Africa after the Civil War. The desire for the repatriation of the previously enslaved African Americans is the conclusion of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s bestselling novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin and the dream of many US politicians for whom emancipation did not include a black future within the territory of the United States.

The ship never sails, it is adrift, without crew. Nothing in Freedom is submerged all the images rise to the surface as she turns each page with a rhythm controlled by her hand. She realizes that the story is explicitly the unfinished history of Enlightenment humanism in black and white: the impossible story of modernity projected into the future of the Atlantic world.

The Captain is too busy to sail the ship anywhere as he is too deeply entangled in the remains of the “libidinal economy of slavery:” “reposed in his favorite armchair in the parlor of a well-appointed brothel. His testicles were in the firm but steady grasp of a too young nigger wench, who, coincidentally was the lost daughter of N___.” She turns a page and the story moves on leaving the daughter behind, forever grasping the testicles of a Captain neglecting his duties.

She has to remind herself that what she is reading is a pop-up storybook, a form associated with children, a Peter Norton Christmas gift. Walker taunts her with her expectations of the form. It is certainly not a book for children though there are children in the book who embody a future that never comes. With the Civil War over N finds herself: “in the holding compartment of a dank and too old ship, she and about forty others, contraband of war,” among whom are two boys, twins, named respectively Hannibal and Cane, aged about twelve. These she decided to take into her custody, “seeking to rewrite history (as she knew it) in one fell swoop.” But, the next morning, “when she awoke, she discovered her two boys were dead tangled in each other’s arms…. A mouse was nibbling at Cane’s testicles.

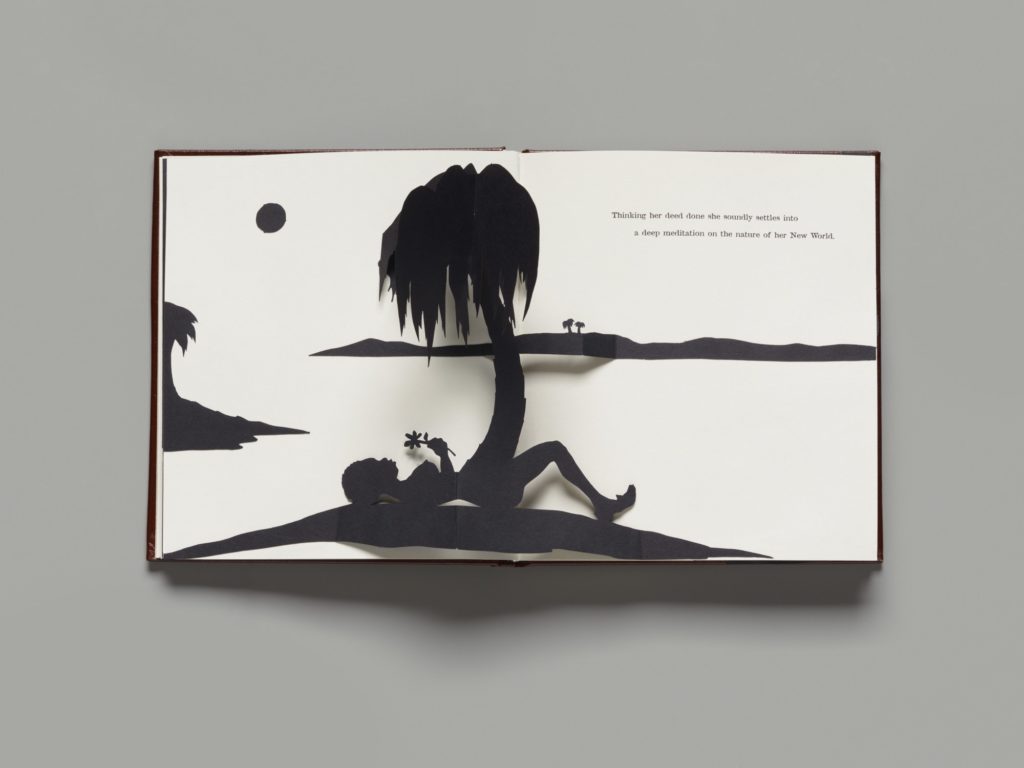

The artwork is a complex interrogation of freedom and futurity suggesting that each or both is fable or fabulation. While Hannibal and Cain are dying, N’s meditation on the new world evokes the Caribbean picturesque. The silhouette sculpts the female body into one piece with land and palm tree, an organic relation to the island that rises toward her as the pages open. She sees one leg lift and become a palm tree under which N lies on her back, flower in hand. The dreaming evokes a future Antilles in which N will be but an element in the landscape of a tropical paradise. In this meditation on the nature of her New World, nature acquires another meaning as a palm tree grows into a substitute leg lifting upward, opening to question whether, in the future, the New World N that dreams into being is a place she can claim, a landscape that will claim her, or a vision of an integration of person and environment.

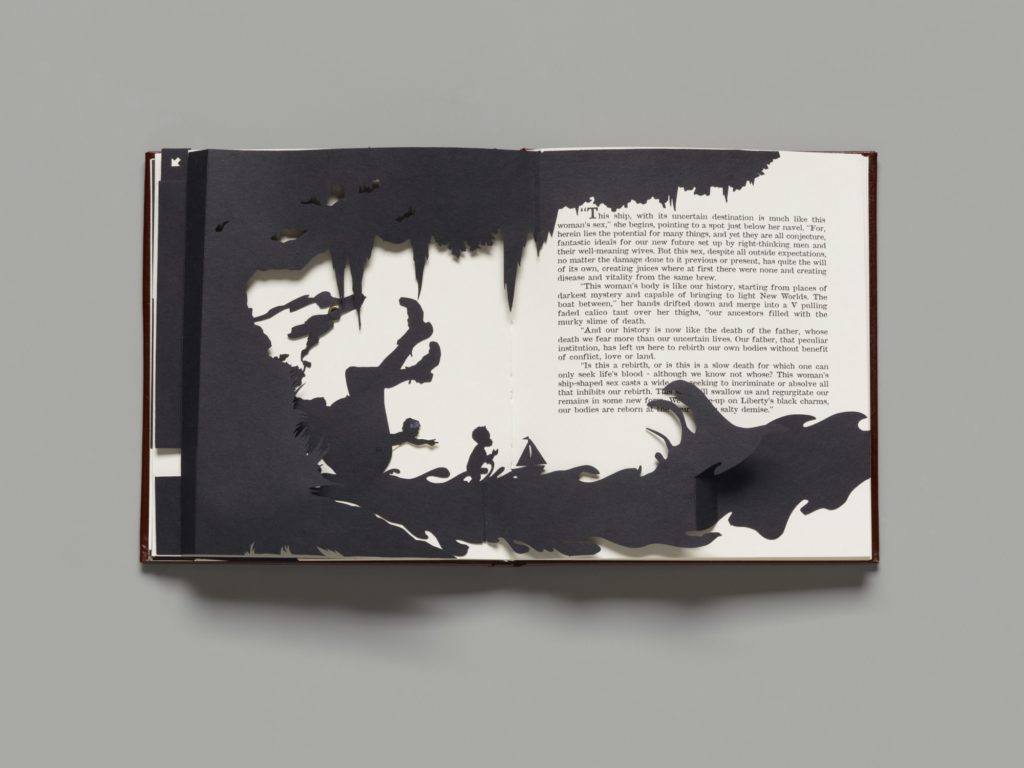

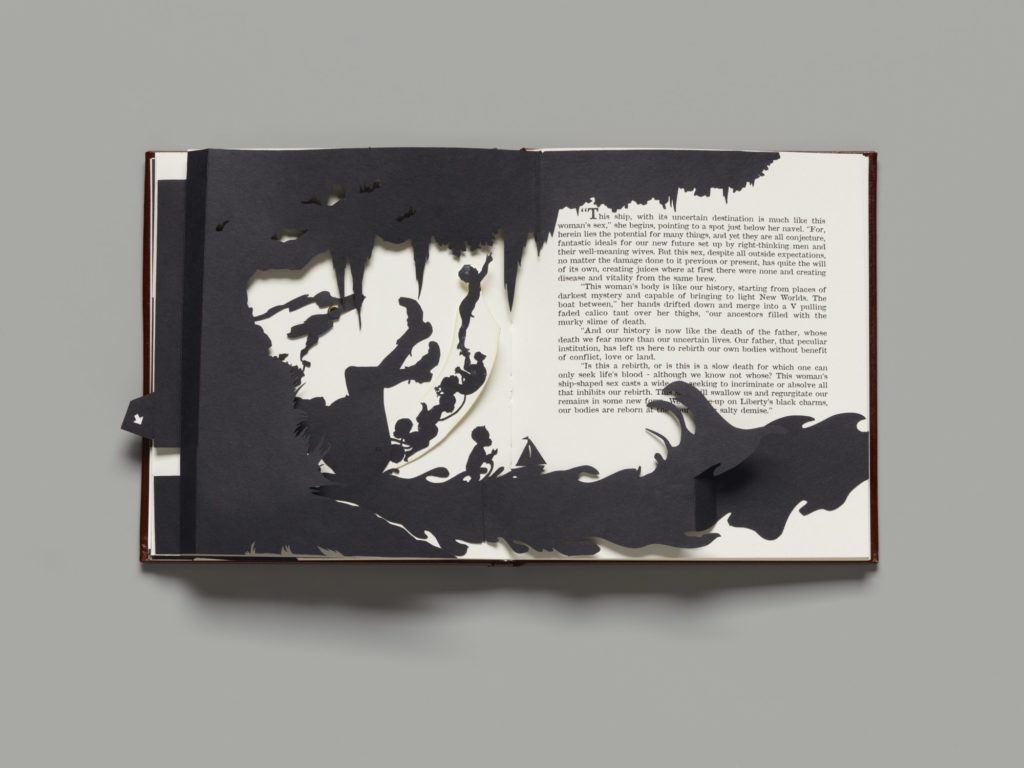

When she turns to the next page black paper trees pop-up to form a half circle which meld with waves – the silhouette frames three sides cradling figures as they sail toward the unknown. A woman smoking a pipe leans against and seems to emerge from, the trunk of a large tree. About to set sail itself the issue from its womb is launched into the waters.

Then she sees a lever, placed behind the tree on the left with a white arrow pointing down. She lowers the lever and the woman’s body falls backwards into the tree while more children are launched upward from between her legs as if she was giving birth to aspirations. But where will they fall? All she can do is replace the lever in its original position, which returns the issue to the womb while she reads N’s question:

Our father, that peculiar institution, has left us here to rebirth our own bodies without benefit of conflict, love or land. Is this a rebirth, or is this a slow death for which one can only seek life’s blood – although we know not whose?

She ponders the implications of N’s question, but comes to no conclusions. All she can do is turn the page to find a young female child stepping off the lip of the final wave into a blank page, a white page and an unknown future.

Any possible future is carried in this vessel; a womb/ship that “our ancestors filled with death.” The text resolves N’s interrogation of whose life blood. In a final radical break with form, as if she could harbor any doubt, as if she still clung to the possibility that the children could be reader’s and/or listeners, or metaphorically or materially the future. She is abruptly reminded that the children are dead, though they still float, nearby.

This is an impossible story told in a form, a pop-up book, which, she is convinced, cannot possibly contain its political and philosophical implications. Then she wonders if her conviction is misplaced, her statement untrue? On second thoughts perhaps Walker returns the form of the children’s story to the brutalities of its origins in the fairy tale? An impossible story of violation and death told to unbelievers and circulated to an elite for their Christmas delight.

She is left as a reader, as a viewer, with what appear to be many open questions: what will issue from this space in the future when we move the lever; who cares about what emerges or not this place, this womb, is the future. A ship and womb adrift at the crucible of emancipation; what will issue from that hold of darkness? Walker withholds, refuses resolutions and she is left to dwell with its uncertainty, its ambiguity, remaining within the impossibility of the story.

And perhaps it is with the impossible stories that she must linger.

Parallax – Mutation – Transformation

An adult human lies on a floor about to give birth; his hands are tied together with his pants, his arms raised above his head. The protagonist, Gan an adolescent male, kneels on the cloth between the hands. T’Gatoi, a many segmented creature with bones and four sets of limbs per segment, extends a claw from one of these limbs, raises it above an area of the abdomen which is pulsing with movement, then comes to rest on an area of brown skin. The skin stiffens at the touch and the man weeps helplessly. T’Gatoi places the man’s shirt between his teeth, wraps the lower part of her three-meter-long body around the legs of the man and holds him tight.

In one swift movement, T’Gatoi slices open his abdomen. With a claw she carefully picks out the fat red grubs which, having devoured their egg sacs, have buried themselves deep into the man’s flesh, preparatory to consuming him from the inside out. A sound left the man the like of which Gan had never before heard from anything human. Gan is well aware he is watching his future for T’Gatoi will impregnate him that same night. This use of his body as host will ensure the future existence of beings called the Tlic.

Octavia Butler’s short story, “Bloodchild,” takes place over the course of one evening on a distant planet. Like Gan she is seduced by T’Gatoi, with her velvet underside and sensuous motion: undulating as if swimming underwater. This description of sensuous motion reminds her of one of Ellen Gallagher’s Watery Ecstatic works from 2005.

© Ellen Gallagher. Courtesy Gagosian.

T’Gatoi is a Tlic government official in charge of a colonial “preserve” within which “Terrans” are confined. In an extraordinarily intense 26 pages she is captivated by the erotics and politics, the pleasures, fears and dangers of sex and obligation between two different types of beings that renders the politics of gendering and the hybridity of post-coloniality appear extremely naïve.

Butler, with forensic fictional skill, probes the complexities of reproductive politics at work in relations of domination and subordination in a futuristic frame. She learns the backstory of the arrival of brown-skinned Terrans only gradually as the story unfolds. Brown skinned humans have fled to a planet in another galaxy seeking escape from persecution on Earth. They are confined to a colonial preserve because past rebellions have failed, their weapons have been stripped from them and male Terrans are used to incubate the next generation of Tlic. They live, in other words, in a camp with T’Gatoi as a paternalistic commandant as their benefactor or patron.

Butler recreates the seductions and ruses of a racialized libidinal economy in a story, which is not, ultimately, a story of slavery but of enslavement to the imaginative limitations of the gendered subjectivity codified in modernity.

Octavia Butler, opens her novel, Wild Seed, in 1690 in Dahomey, now Benin, a West African state founded in the sixteenth century which became famous for its all-female military units, the Mino, popularly known as the “Amazons.” The novel spans the Atlantic trade, colonial America, plantation slavery in the US and concludes in California on the eve of the Civil War. But Wild Seed does not narrate the history of enslavement, rather Butler displaces the politics of slavery’s libidinal economy into a transhistorical story of a struggle for power between two figures, each of whom have lived for hundreds of years before they meet: Doro, nominally male who survives by constantly inhabiting new bodies, killing the host each time; and Anyanwu, the name of an Igbo deity, nominally female, who is a shape shifter.

Through these conceits Butler narrates a power struggle between predator and prey. It is Doro’s multiple forms, she concludes, that allows Butler to explore the exercise of patriarchal power dislocated from the particularities of racialization, ethnicity or gendering. Doro seeks profit from reproduction/production of people with particular traits; he makes claims to Anyanwu’s womb because he recognizes her value as potential breeder. But despite the knowledge that Doro is the source of her exploitation she is both repelled by and attracted to him this allowing Butler to explore the carnal nature of modernity.34

Genre labels like science fiction and Afrofuturism are insufficient to capture Butler’s exploration of degradation, violation, oppression, and alternative modes of belonging. Anyanwu’s only means of escape from the predatory exploitation of Doro is through her empathetic ability to shape-shift and take refuge in the ocean.

© Ellen Gallagher. Courtesy Gagosian.

Wild Seed is an origin story recounting a persistence struggle against patriarchal domination. It transgresses conventional temporal and spatial boundaries and modes of affiliation and obligation, creating alternative ways of knowing and being. There is no allegiance to race, nation, nationalism or affiliation to citizenship or politics of place.

In Butler’s novel Dawn the protagonist Lilith awakens to find herself in a small room in a living, breathing Oankali and Ooloi ship circling a destroyed planet earth. The only hope for the survival of humanity in any form is through sexual reproduction with Oankali and Oolo and the birth of a future species that will carry genes farmed from across the universe.

In her fiction Butler challenges the limits of Enlightenment humanism and its racialized and gendered ways of knowing, being and becoming. In this break or cut Butler creates an alternative humanism one that transcends tightly bounded understandings of humanity and shape-shifts readers into the imaginative and political realization of species being that Sylvia Wynter advocates.

She is convinced that to realize and preserve a future it has to be constantly re-shaped, unmasked and re-presented in recognition of our own multiplicity35 and of the interdependence of species and ecologies. What appear to be unbridgeable differences between beings have to be crossed and alliances with life forms that appear distant from or repel humans have to be negotiated and then cemented for a future existence for all. This is a move far beyond what has so far been defined as Afrofuturism.

Could we become capacious enough to build solidarity not only across binaries of gender and borders of race, ethnicities, indigeneity and nation to include all species? Accumulation equals subtraction equals dispossession and we are being dispossessed of this planet. If our futures have been foreclosed, if life itself is accounted of no value,”36 if the planet is being sacrificed on the altar of finance capital and fossil fuels perhaps insisting upon the interdependence of all organisms could become the essential work in the unfinished project of freedom. It is, at least, a place from which to begin.

- Alexis Pauline Gumbs, M Archive: After the End of the World (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018), 48. ↩

- Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, trans. Betsy Wing (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997), 5. ↩

- Stephen Leahy, “Microplastics are raining down from the sky,” National Geographic, April 15, 2019, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/2019/04/microplastics-pollution-falls-from-air-even-mountains/; Jamiles Lartey and Oliver Laughland, “This is Cancer Town,” The Guardian, May 6, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/ng-interactive/2019/may/06/cancertown-louisana-reserve-special-report; Emily Holden, “10 US oil refineries exceeding limits for cancer-causing benzene, report finds,” The Guardian, February 6, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/business/2020/feb/06/us-oil-refineries-exceeding-limits-for-cancer-causing-benzene-report-finds. ↩

- This Land is Your Land, “Trump finalizes plans to open Utah monuments for mining and drilling,” The Guardian, February 6, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/feb/06/trump-utah-national-parks-energy-development-drilling. ↩

- Carl Zimmer, “Birds Are Vanishing From North America,” The New York Times, September 19, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/19/science/bird-populations-america-canada.html. ↩

- Tartie, “Ablaze.” See Binnie Klein, “’Ablaze’: A Haunting New Song about Australia’s Wildfires,” Yale Climate Connections, February 10, 2020, https://yaleclimateconnections.org/2020/02/ablaze-a-haunting-new-song-about-australias-wildfires/. ↩

- Glissant, Poetics of Relation, 206. ↩

- Ed Yong, I Contain Multitudes: The Microbes Within Us and a Grander View of Life (New York: Harper Collins, 2016). ↩

- Rex Weyler, “The Ocean Plastic Crisis,” Greenpeace, October 15, 2017, https://www.greenpeace.org/international/story/11871/the-ocean-plastic-crisis/; Alejandra Borunda, “This Pregnant Whale Died with 50 Pounds of Plastic in her Stomach,” National Geographic, April 2, 2019, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/2019/04/dead-pregnant-whale-plastic-italy/; Trevor Nace, “Whale Died Of Starvation After Eating 80 Plastic Bags Off Thailand’s Coast,” Forbes, June 4, 2018, https://www.forbes.com/sites/trevornace/2018/06/04/whale-died-of-starvation-after-eating-80-plastic-bags-off-thailands-coast/#35a9d0606c31; Philip Hoare, “Whales are starving – their stomachs full of our plastic waste,” The Guardian, March 30, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/mar/30/plastic-debris-killing-sperm-whales. ↩

- Anna Turns, “Saving the Albatross: ‘The War is Against Plastic and they are Casualties on the Frontline,’” The Guardian, March 12, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/mar/12/albatross-film-dead-chicks-plastic-saving-birds. ↩

- Gumbs, M Archive, excerpts from “Archive of Dirt,” 44, 45, 46 ↩

- Katie Campbell and Ken Christensen, “Where does America’s E-Waste End Up? GPS Tracker Tells All,” PBS News Hour, May 10, 2016, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/science/america-e-waste-gps-tracker-tells-all-earthfix; Hannah Ellis-Petersen, “Deluge of Electronic Waste Turning Thailand into ‘World’s Rubbish Dump,’” The Guardian, June 28, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/jun/28/deluge-of-electronic-waste-turning-thailand-into-worlds-rubbish-dump; Colin Lecher, “American Trash: How an E-Waste Sting Uncovered a Shocking Betrayal,” The Verge, December 4, 2019, https://www.theverge.com/2019/12/4/20992240/e-waste-recycling-electronic-basel-convention-crime-total-reclaim-fraud; Shola Lawal, “Nigeria has Become an E-Waste Dumpsite for Europe, US, and Asia,” TRT World, February 15, 2019, https://www.trtworld.com/magazine/nigeria-has-become-an-e-waste-dumpsite-for-europe-us-and-asia-24197 ↩

- “Democracia en Extinción” YASunidos, accessed October 20, 2020, https://sitio.yasunidos.org/en/yasunidos/ojo-en-petroamazonas/20-comunicacion/campanas/51-democracia-en-extincion. ↩

- David Wallace-Wells, The Uninhabitable Earth: Life after Warming (New York: Tim Duggan Books, 2019), 210 ↩

- Farhana Yamin, “Global Rebellion: Die, Survive or Thrive?” The Ecologist, April 18, 2019, https://theecologist.org/2019/apr/18/global-rebellion-die-survive-or-thrive; Amber Bracken and Leyland Cecco, “Canada: Protests Go Mainstream as Support for Wet’suwet’en Pipeline Fight Widens,” February 14, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/feb/14/wetsuweten-coastal-gaslink-pipeline-allies; Sam Levin, “Dakota Access Pipeline: The Who, What and Why of the Standing Rock Protests,” The Guardian, November 3, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/nov/03/north-dakota-access-oil-pipeline-protests-explainer. ↩

- Stephen Best and Saidiya Hartman, “Fugitive Justice,” Representations 92 (Autumn 2005): 4. ↩

- Ottobah Cugoano, Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil of Slavery (London, 1787), 112, quoted in Best and Hartman, “Fugitive Justice.” ↩

- Johannes Lang, “Tear Down the Fortress: Europe and the Refugee Crisis,” Harvard Political Review, April 3, 2019. ↩

- Elliot Hannon, “The U.S. Detained a Record 69,550 Migrant Children This Year,” Slate, November 12, 2019, https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2019/11/u-s-detained-record-migrant-children-separated-parents-2019.html. ↩

- Derek Walcott, Collected Poems, 1948-1984 (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1986), 364. ↩

- Mike Rubin, “Infinite Journey to Inner Space: The Legacy of Drexcyia,” Red Bull Music Academy, June 29, 2017, https://daily.redbullmusicacademy.com/2017/06/drexciya-infinite-journey-to-inner-space. ↩

- Netrice R. Gaskins, “DEEP SEA DWELLERS: Drexcyia and the Sonic Third Space,” Shima Journal 10, no. 2 (2016), https://www.shimajournal.org/issues/v10n2/h.-Gaskins-Shima-v10n2.pdf. ↩

- See Kodwo Eshun, More Brilliant than the Sun: Adventures in Sonic Fiction (London: Quartet Books, 1998). ↩

- In a founding text of the field of African American studies, The Souls of Black Folk, W.E.B Du Bois condemned, “The red stain of bastardy” that issued from the wombs of black women constituted a “hereditary weight” of betrayal, a legacy that fell on the shoulders of black men and prevented the flowering of black manhood.” Hazel V. Carby, Race Men (Cambridge: Harvard University, Press, 1998), 33 ↩

- Ellen Gallagher and Adrienne Edwards, “Below the Surface: Ellen Gallagher discusses the origins of her artistic practice with Adrienne Edwards,” Gagosian Quarterly (Summer 2017), https://gagosian.com/quarterly/2017/05/01/below-surface/. ↩

- The series keeps evolving. See Morgan Quaintance and Ellen Gallagher, “Ellen Gallagher at Tate Modern reviewed by Frieze,” Hauser & Wirth, November 7, 2017, https://www.hauserwirth.com/stories/2305-ellen-gallagher-tate-modern-london. ↩

- “Ellen Gallagher, Bird in Hand, 2006,” TATE, accessed October 20, 2020, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/gallagher-bird-in-hand-t12450. ↩

- Eduardo Kohn, How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology Beyond the Human (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2016), 75. ↩

- Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe 12, no. 2 (2008): 3. ↩

- Wangechi Mutu, “Artist Statement,” Callaloo 37, no. 4 (2014): 921-928. ↩

- Stephan Palmié, Wizards and Scientists: Explorations in Afro-Cuban Modernity and Tradition (Durham: Duke University Press, 2002), 5, 7-9. ↩

- Glissant, Poetics of Relation, 5. ↩

- Jennifer L Morgan, Laboring Women: Reproduction and Gender in New World Slavery (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), 83. ↩

- Palmié, Wizards and Scientists, 36. ↩

- Young, I Contain Multitudes. ↩

- Ottobah Cugoano, Thoughts and Sentiments, 112, quoted in Best and Hartman, “Fugitive Justice.” ↩