Written By Ned Prutzer

In Human Machine Reconfigurations: Plans and Situated Actions, Lucy Suchman argues that all plans or blueprints are contingent upon different modes, styles, and visions that precede the plan itself. Plans are rendered “abstractions over action” rather than final, complete, or faithful articulations of action.1 There are myriad contexts, actors, institutions, and agencies producing effects that are unanticipated by the blueprint. The ways in which plans often fall short is thus a worthwhile site of analysis. I want to focus on this notion of blueprints’ failure in precision to identify broader modes of representation underpinning locative art projects while critiquing their faith in precision and objectivity.

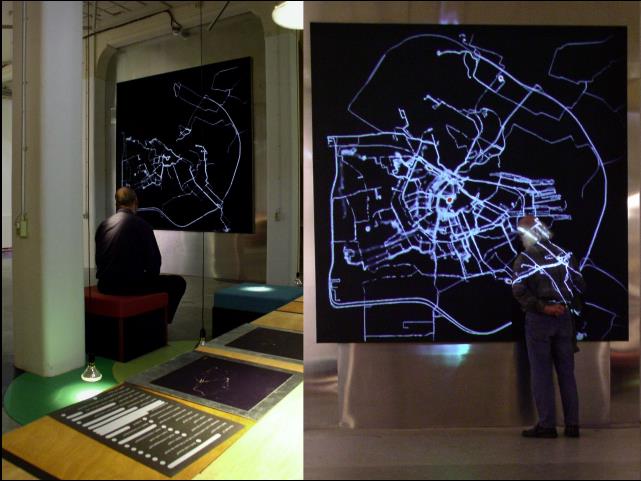

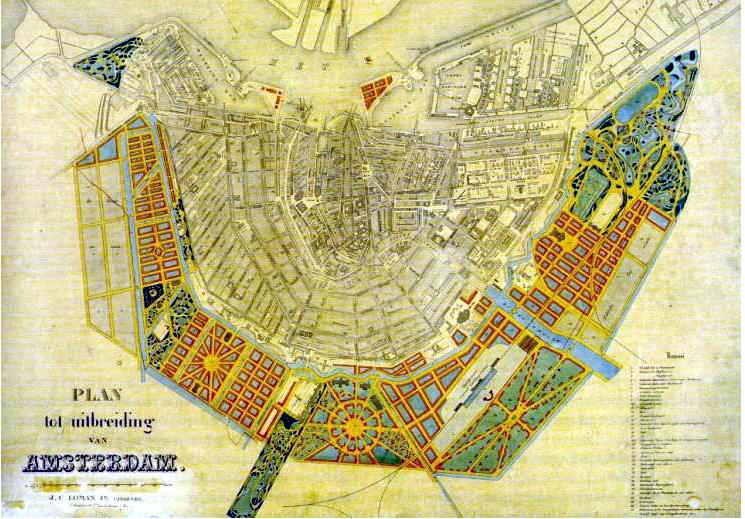

For Amsterdam RealTime, an early locative art project from 2002, locative artist Esther Polak traced subjects’ movements with geospatial technologies as they walked, biked, or drove through Amsterdam. An animation of each subject’s traces results. When aggregated onto a screen, these traces draw out the Amsterdam city grid as the subjects have enacted it. Amsterdam RealTime was displayed as the final installment of the Maps of Amsterdam 1866-2000 exhibit at the Amsterdam City Archive.2 The Amsterdam RealTime website, still running the visualization and hosting an archived website, situates the project within this larger exhibition thusly:

The project provided visitors of the exhibition with a special experience: having just seen 150 years of cartography, which has always been influenced by technology and the cartographer’s vision, the visitor was exposed to a contemporary live version of that very same Amsterdam, created with today’s technology.3

Upon entering the exhibition space for Amsterdam RealTime, each visitor, through infrared detection, would erase the standing animation and start a new subject’s trace on the screen.

Figure 1. Screenshot, Amsterdam RealTime online, 2002.

Additionally, the exhibit included an archive of each of the subjects trace on cards that included their age, vocation, and thoughts on Amsterdam RealTime. This information was aggregated through an online form subjects would submit from which participants for the project were selected. The cards were laid out on a table found across from the screen in the dark room where the project was displayed. Users can still access this information online by clicking on each subject’s individual window on the right side of the map being drawn.4

Figure 2. Screenshot, Amsterdam RealTime online, 2002.

As an early locative art exhibition, Amsterdam RealTime embodies the past, present, and future of locative representation. This embodiment manifests both through the project’s relation to its surrounding exhibition space as well as its anticipation of the locative’s focus on surveillance. The specific aesthetic nature of Amsterdam RealTime exemplifies what I will term the locative uncanny within the domain of locative representation. The locative uncanny describes a certain propensity of locative work to decontextualize the very forms it appropriates and to showcase, ironically, the impossibility of precisely representing mobility and the everyday with geospatial technologies.

Regarding the former, I identify affinities that Amsterdam RealTime shares with graffiti and the aesthetic of the technological sublime, which romanticizes and simplifies representations of technological infrastructure. Brian Holmes discusses the technological sublime, which aestheticizes ambivalence toward technology, often within landscape depictions of technological infrastructure, and naturalizes it through imprecise representation, resulting in blurring.5 I explore the involved systems of representation as blueprints, rather than the finished product of study, thus treating the blueprint as a process. This involves examining the city and the involved systems of display (locative art, graffiti, the technological sublime, and the broader cartographic imaginary) as blueprints in and of themselves, alongside the finished project.

My identification of the locative uncanny applies, however, not just to Amsterdam RealTime, but locative representation itself. Aside from recognizing the aforementioned appropriations within other locative projects, I will distinguish the politics of motion within Amsterdam RealTime’s operations as a system of display that reflects how surveillance in the locative mode is now often seen as permissible. The project, in some ways, avoids the resonances of surveillance within not only its original exhibition space but also its current online record. Overall, Amsterdam RealTime is a participatory system of tracing, but it is not just a blueprint of the city. It charts the contemporary anxiety within the locative media landscape as much as it charts the everyday movements of its participants. As such, Polak’s emails, interviews, and statements on the project are instructive of the contemporary moment and worth analyzing. Simultaneously, the project’s relation with the larger Maps of Amsterdam 1866-2000 exhibit locates mapping as a practice within a history of disruption and failure. 6

Contextualizing Amsterdam RealTime

Considering how early it emerged in the history of the form, Amsterdam RealTime serves as a kind of blueprint of locative representation. Locative representation is now ubiquitous within contemporary media artifacts. The use of the term ‘locative’ itself has been applied to an ever-increasing range of media and art projects, ranging from music, oral history, and psychogeographic projects to everyday social networking applications. In this wide application, it has lost much of its nuance and meaning. It can, however, still be used as a useful and complex term. Marc Tuters notes that while the influence of the term has declined, it retains significant heuristic value in crafting innovative artistic interventions into processes of place-making.7 As such, investigating such an early engagement with the form of locative representation within an institutionally sanctioned art exhibition can illuminate the complex position locative media inhabits within the contemporary media landscape.

Discourses of surveillance are pivotal to that very landscape in relation to locative representation. Andreas Broeckmann elucidates this tension:

I have always understood the term “locative” as pointing in both directions, the potential for enriching the experience of shared physical spaces, but also fostering the possibility to “locate”, i.e. track down anyone wearing such a device. This does turn the “locative media” movement into something of an avant-garde of the “society of control.”8

While Polak discusses the resonance of surveillance within Amsterdam RealTime, she is mainly defensive regarding this association:

With Amsterdam Real-Time . . . the main goal was to give people a sense of their own perceptions. We did not want visitors to adopt the ‘surveillance’ perspective or the voyeuristic gaze, we wanted them to try to identify as much as possible with the participants. We used a theatrical method: namely we conveyed participation in the project as a very special, even enviable opportunity.9

Here, Polak includes autonomy and theatricality within the goals of the project. Notably, she excludes an exploration of the ramifications of the art practice or the technologies that facilitated it. This, in a way, seems to discourage critical self-reflexivity concerning the nature of this particular technological practice.

While my invocation of surveillance here may be misleading in that locative work may not actively contribute to state power, the technological infrastructure foregrounding its visualization is certainly derivative of state power. While not based on overt state power per se, such projects aestheticize the output of a state-controlled satellite system while glossing over what could be done (and now is being done) with such an infrastructure. This is a naivete typical of early locative work, before locative projects started engaging in critique of surveillance and consumerism through the very technologies which facilitate it. Instead of dealing with overt state power, the political stakes I trace in the disorder of the locative delve more so into a masking of contingencies, a telling imprecision in the representation of the objects of focus, and, most importantly, an appropriation of different representational forms that depoliticizes, rather than infusing new politics into said forms.

Despite this, Polak does address what she sees as the role of geospatial technologies within the project:

The social or political consequences of surveillance technologies (such as GPS), for example, are part of the work, but they’re not my primary interest. As a ‘new media’ artist I try to develop a relationship to the place of technology in society. This involves developing a certain level of engagement, but that doesn’t always entail being critical. It is essential, though, to avoid negating your audience’s critical position. In my work I offer an open approach that gives the audience a great deal of space to draw their own conclusions.10

This sentiment is quite different than that of many locative artists. There are a number of such artists who “work with . . . technologies to critique their role in promoting a consumer based society or bringing about a ‘society of control.’”11 Polak seems reticent to identify this drive within Amsterdam RealTime. Perhaps this is due in part to how early the project is in the locative art movement, but it is still a deviation worth noting. It is peculiar that the project downplays the resonance of surveillance when so much of the project – both in terms of what it represents and how it functions as an installation – engages in surveillance and motion detection. As Jason Farman, a notable scholar of mobile media, identifies, “[m]aps are not simply representations of ontological reality; instead, they signify space in a very particular way that is designed to be read to fit with the current cultural hegemony.”12 Yet Amsterdam RealTime distances itself from the surveillance society narrative. It aims instead, paradoxically, to represent the everyday with precision while avoiding the topic of surveillance.

Considering the current prevalence of the surveillance narrative in an increasingly location-aware media environment, Polak’s reticence toward the narrative contrasts greatly from the contemporary moment. The recent development and planning of “smart cities” exemplifies a telling and critical juncture for the future of locative representation. Luca Calderoni, Dario Maio, and Paolo Palmieri describe smart cities as places “where citizens are interconnected to each other and to the city itself, which provides a constant flow of information, personalized to the user’s needs and preferences.” They also purport that the interconnection and personalization within smart cities yields a more autonomous and informed citizenry.13 Such inferences fashion smart cities in the popular imaginary as the “cities of tomorrow.”14 Additionally, Calderoni et al frame locative media as productive within the smart city. Citing security systems as an example, they speculate that analyses of location-based information in urban settings can yield a better understanding of both the individual and the city.15 When considering Amsterdam RealTime, the current fascination with the potential of location data, particularly within security, gives new meaning to the project. The continuities and ruptures Amsterdam RealTime poses as an early work of its kind to the present moment underscore a change in framing with its continued exhibition online. While Polak framed the project as charting the everyday, it now in many ways charts the very discourses it attempted to avert through the new ways location-based data have been implemented and framed.

Aside from resisting surveillance-oriented framings of Amsterdam RealTime, Polak pays little attention to how, in her emphasis on participation, participants could have interpreted the project in an oppositional manner. Subjects could have used the devices to draw traces that would have been counterintuitive to project’s aim: to prove that the city grid could be drawn solely through participants’ everyday practices. The project, then, emerges as more of a controlled and constrained activity. Polak initially wanted to allow for groups to draw out names or borders, but expressed this desire in terms of objectivity rather than resistance to the project’s surveillance resonances. She claimed that the representation would not be compromised through such actions since groups of people would encourage more users to get involved, and more users would increase the representation’s objectivity.16 Polak further identifies objectivity within geospatial technologies, admitting, “I was interested in GPS from the first moment it was introduced to me, because it seemed to be extremely realistic. It told an almost technological truth about an event that had not existed before it was made visible with GPS.”17 As such, Polak affirms a supposed objectivity to geospatial technologies that contrasts with her intended emphasis on the subjective within Amsterdam RealTime. Simultaneously, Polak does not recognize ways that the project could have been subverted in its postulations on the everyday toward ties between technology and surveillance.

Karen O’Rourke elucidates the interpellative activity that Amsterdam RealTime fosters for its visitors. Given that the presence of bounded interpellative exercises within locative art and museum spaces has been well documented, her identification is not surprising.1819 O’Rourke contends the project made visitors identify with the subjects instead of merely looking on from a distance.20 Ironically, however, the prominence of the locative mark and subjects’ identification with the traces was not, to Polak, the point of the exercise:

The point of departure was not to emphasize the interaction between people and the traces they leave behind, although we did print out the individual routes and hand them out to each participant as a souvenir. Looking back now, I think it was a rather naive decision: We had absolutely no idea how much impact the print-outs would have on the participants. People pored over their printed-out routes in utter fascination and couldn’t wait to share their stories.21

The subjects’ enthusiastic identifications with their own traces is unsurprising, as “‘people have always felt the need to share and express themselves in a public way, sometimes by telling a story or posing a question . . . . Place marking is thus an evocative form of place making.”22 Yet, through her use of infrared detection, Polak also downplays the aggregate real-time image of the subjects’ movements. As each new visitor enters, Polak replaces the aggregate image with a single subject’s trace on the screen. Afterward, the screen proceeds with the aggregate real-time imaging. Thus, Polak wants visitors to recognize how place is a sociocultural production that results from an aggregate form of individual’s everyday practices. While the appearance of the individual trace appeals to the visitor to identify with the project’s subjects, Polak sees this appeal as problematic. The role of the individual in relation to the aggregate, then, is a complicated one within the project. This is despite the project’s argument toward individual agency in creating the city through everyday practices. The project’s presentation of the traces sparks this complexity, and Sigmund Freud himself invokes tracing and recursion in discussing the uncanny.

The Locative and the Uncanny

Freud claims that repetition can “awaken an uncanny feeling, which recalls that sense of helplessness sometimes experienced in dreams.” He describes himself wandering while lost, claiming that a startling, uncanny feeling arose within him as he kept encountering the same signs, landmarks, and people in the circles he ran. To Freud, such circumstances underscore “the idea of something fateful and unescapable.”23 Anthony Vidal extends Freud’s conceptions to incorporate the corporeal and the psychological into the architectural. He treats the uncanny in a broad manner, rendering it a “category of pure indeterminacy” between what is known or comfortable and what has been once concealed but unintentionally revealed.24 An “unsettling merging of past and present” often results.25 This matches Freud’s characterization of the uncanny as a “lurking unease,” and stands as a “treaty between the subversive and the comforting.”26

Though I use the term “uncanny” in relation to the locative largely to illuminate appropriation, my reading of the uncanny also fits with the particular history the term has within critical thought. Amsterdam RealTime eschews viewers’ interpretive comfort of stability and cohesive direction in the tracing of its realtime routes while blurring what lies in the built environment and who navigates it. These dynamics of the uncanny in terms of privation and obfuscation, respectively, tie directly into the project’s purported depiction of the ambulatory and the everyday. The visitors’ act of witnessing the recursive drawing of the same traces from the project mirrors Freud’s sense of helplessness in repetition. Likewise, Vidal’s emphasis on concealment, unease and overlapping temporalities illuminates not only what is conveyed and obscured within the representation itself, but also how the object was and continues being received under the uncanny temporality of its “RealTime” title.

While I will cover the reception of the project’s uncanny nature later, for now I will emphasize how this uncanny nature relates to other early locative projects of Amsterdam RealTime’s time. To start, the locative reflects the project’s uncanny temporality in its engagement with the subjective dimensions of place. To this end, Connor McGarrigle deems locative projects “a new site for old discussions about the relationship of consciousness to place and other people” and “[a] context within which to explore new and old models of communication, community and exchange.”27 He subsequently overviews various early locative projects designing exercises that confront the built environment through innovative techniques which facilitate the Situationist dérive. He includes, among other projects, “Teri Rueb’s Drift, Valentina Nisi’s Media Portrait of the Liberties, and 34n 118w (Knowlton, Spellman, Hight).” He also mentions Christian Nold’s Biomapping from 2004, a relevant inclusion in relation to the uncanny.28 In walking through San Francisco for one of the project’s maps, Nold’s subjects convey anxiety through their Galvanic Skin Response (GSR) results as many of them relay memories of what they pass, reach dead ends, and circle back.29 It is the captured anxiety in this wandering that resonates with Freud’s view of the uncanny. Other locative works, however, complement the uncanny more in terms of its investment in repetitious wandering though space. McGarrigle specifically invokes “SocialFiction’s self-declared algorithmic psychogeographical.Walk,” which issues “instructional sequences of later situationist dérives with the more prosaic technology of pen and paper, illustrating, I would argue, the common purpose of much locative art, whether it employs locative media or not.”30 McGarrigle’s identification of the locative’s iteratively designed dérives extends the application of the uncanny to a variety of locative work rather than just Amsterdam RealTime.

Alongside Situationism, other artistic styles prior to the locative movement placing location as a key signifier also factor into the uncanny nature of Amsterdam RealTime. But that particular facet of the project, coupled with the aforementioned complex dimensions of motion within the original exhibition space of Amsterdam RealTime, underscores a need for self-reflexivity upon the project’s technological practices. The dimensions of motion are just one of several aspects of the project that render it a unique system of display. In the next section, I address these other pertinent aspects in further detail.

Amsterdam RealTime as a System of Display

Amsterdam RealTime functions as a system of display on two levels. These two levels resonate with the invocations of everyday practice and surveillance, respectively, within the project. First, Amsterdam RealTime represents a system – a city – as it is constituted by its subjects’ everyday practices, thus representing the project as a blueprint of the processes behind constructing the city. Situationism, often linked to locative art, helps clarify this dynamic. While Situationism has historically been applied to the study of graffiti in relation to the urban environment, Huhtamo describes that in this application, “it is surprising that public screens have received little attention, considering the huge impact of Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle.”31 One might consider the project as a Situationist dérive, a performative cartography which entails “walking across urban space, enacting random but creative encounters” while contesting “the controlled modernist dream of the city.”32 To this end, any aspect of the city that Amsterdam RealTime’s subjects do not engage in is excluded from the representation. This reclaims the city from an economic narrative to one of communication. Within the former, capital and infrastructure sustain a sense of place. Within the latter, everyday practices of culture—rather than the economy of the city—characterize place. This positions the project in a vexed relation with well-known theorizations of space and place, notably Henri Lefebvre’s notion that spatiality is fluid and produced by relationships with capital, power, and hegemony, as often manifested through the body in motion.33

Ironically, the resonance of Amsterdam RealTime with Situationism could also be construed as a deviance from Situationism in its recreation of the city grid, which Guy Debord and the Situationists actively countered in works like The Naked City.34 While the latter deconstructs and rearranges the city grid, Amsterdam RealTime presents the grid as it is through the traces. However, the project also in a sense jettisons that very grid. It only portrays elements of the city that the subjects’ movements encompass. Amsterdam RealTime, then, emphasizes aspects of the city grid imbricated commonly with subjects’ everyday practices, in line with Michel de Certeau’s notions on the everyday. De Certeau argues that “everyday life invents itself by poaching in countless ways on the property of others,” as “[m]any everyday practices (talking, reading, moving about, shopping, cooking, etc.) are tactical in character.” For de Certeau, this means that subjects must come together to forge their own representations of place.35 Yet Amsterdam RealTime deviates from his approach in that it ignores infrastructure and the commercialized nature of city sign systems while still trying to trace the hidden poesis of which de Certeau speaks. To this end, Polak relates that “[e]verywhere you look there are signposts and information plaques telling you how to experience the natural world around you: all kinds of signs telling you how to look.”36 Thus, while Amsterdam RealTime appropriates such theories of space and place in borrowing their emphasis on subjectivity and everyday practice, it does not necessarily do so faithfully. These specific appropriations are just some of the many appropriations embedded in my identification of the locative uncanny.

Second, Amsterdam RealTime itself functions as a system of representation, surveilling the movements of subjects in the city through screen media, within a broader system of display – locative representation. As such, Amsterdam RealTime functions as a recursive performance founded through infrared technologies within the exhibition space, with the audience playing an active role in manipulating the project’s presentation on the screen. This dynamic reveals much about the exhibition’s politics of motion, reflected not only in how subjects are surveilled but also in how the movements of the viewers within the exhibition space are confined between the screen and the archival table. This guiding of movement within the exhibition space again reflects the constraints involved in a project that operates under a frame of subject liberation in representing everyday practices.

Returning to the crux of McGarrigle’s analysis, the locative embraces the Situationist “construction of situation” as epistemology, as the locative entails “developing critical spatial practices and in detourning emergent locative technologies so that they evolve as participatory tools; tools with possibilities for creation rather than additional channels for passive consumption.”37 The construction of situations within these projects become a means of subverting the banality of place and its capitalist logic. Accordingly, the paths that result are often based on the algorithmic and the iterative – “designed,” in McGarrigle’s description of his own locative work, “to avoid what Debord identified as the ‘limitations of chance.’”38 Here, the uncanny, in the traditional sense, emerges in the appeal to the comfort in the ambulatory and the everyday and its placement under scales and logics which render both subversive. For Amsterdam RealTime, subjects and viewers make the dérives recursive, setting into motion Freud’s repetitive wandering in describing the uncanny. This makes Amsterdam RealTime notable in exemplifying the uncanny at work within the locative.

As McGarrigle reminds us, this is certainly not exclusive to Amsterdam RealTime. Having said that, the uncanny fits well within the project’s two levels as a system of display that I have identified. While the first level envisions the everyday as freeing and comforting withing the aforementioned first level of the project as a system of display, the second envisions the everyday as something secretive that must be unveiled through the alternate use of a technological infrastructure often used toward state surveillance. The uncanny mode of representation that results is further exacerbated by the project’s tenuous positionality between the artistic modes of graffiti and the technological sublime.

Locative Representation, Graffiti, and the Technological Sublime

With the project’s levels as a system of display in mind, I argue that the artistic practices of Amsterdam RealTime are located between graffiti and the technological sublime, as the act of being surveilled becomes expressive. Graffiti was first included in galleries in the early 80s, but this inclusion would not last long among prominent exhibition spaces. The tension between public and private space inherent in this exclusion posed too problematic of a site of contradiction for art exhibitions.39 Indeed, there was concern that this very inclusion was a decontextualization of graffiti; in a Baudrillardian sense, graffiti always already serves as an overt intervention in the semiotics of the private.40

Amsterdam RealTime (and locative representation more broadly) has several affinities with graffiti. Amsterdam RealTime borrows the graffiti convention of the tag. According to Luca M. Visconti et al, “tags represent an early expression of street art meant to spread an individual’s name, originating in New York in the 1970s and contesting the marginality and ugliness of social life through the repetition of nicknames or words of rebellion on public walls.”41 Polak’s blueprint of the city re-inscribes the lived environment with names whose work in constructing the city can be both followed and appreciated. The tag in graffiti serves a similar purpose. The legality of each mark, of course, is a key difference. While the graffiti tag is read, in Situationist terms, as détournement and considered impermissible, my identification of the locative tag is read as dérive and considered permissible. In contrast to the dérive, détournement entails a revitalization of everyday signs on an artist’s or subject’s part by placing such signs within new contexts.42 While Amsterdam RealTime affirms the city as a private sphere (a tactic which differs greatly from that of the tag in graffiti), it simultaneously transforms the city into a palimpsest of everyday life – much like graffiti, only via the screen.

Another important consideration is that locative marking is not as overtly threatening to order. Nor does locative representation carry the connotations that graffiti, having been compared to dirt, pollution, and filth, has carried. Nor does it embody a corresponding genealogy of urban otherness and Third World associations construing its practice as filthy and unreasonable that contribute to its continued suppression in public discourse. Yet both artistic forms are concerned with the politics of inscription onto the urban environment (whether it be the built environment or a simulation and the intervention into geographical hegemony involved in these processes).43

To this end, both systems of artistic practice can be situated at the border of a public discourse that frames normative geographical behavior and marking. Both reveal place and the city as a blueprint of fluid and negotiated meanings. Graffiti situates the urban environment as an artifact of private property, while locative projects situate it as an artifact of media urbanism. In this, both forms are reclamation projects of urban space. Additionally, both have a phenomenological resonance, situating place as the site of becoming for the other, as stripping the city of its semiotic register means stripping it of different assumptions of capital. As such, the meanings of both forms change considerably when they are institutionalized within exhibition spaces, albeit in different ways.44

Grafedia, an online facilitator of graffiti, is also pertinent here, as it operates in a very different manner than Polak’s project. First, and perhaps most obvious, grafedia intends to actually mark place via the virtual, whereas Amsterdam RealTime is a wholly simulated exercise translated onto the screen. Second, the artist shares the work of graffiti and his or her tag (which is blue and underlined in tribute to the hyperlink) in advance by uploading it to the grafedia website. Lastly, grafedia has involved more participants, with over 2,000 uploaded contributions.45 However, grafedia and the locative mode are both broader reclamations of space through tagging and technology. Thus, this similarity reveals how Amsterdam RealTime anticipates grafedia in its drive to mark a city through technology.

One can also position locative representation, and particularly Amsterdam RealTime, within the blurred aesthetic of the technological sublime. This naturalization, to Holmes, means that art actively participates in glossing over structures of surveillance by incorporating them into an aesthetic.46 Said aestheticization augments the sense of fear associated with the surveillance practices of Amsterdam RealTime located in the public sphere.

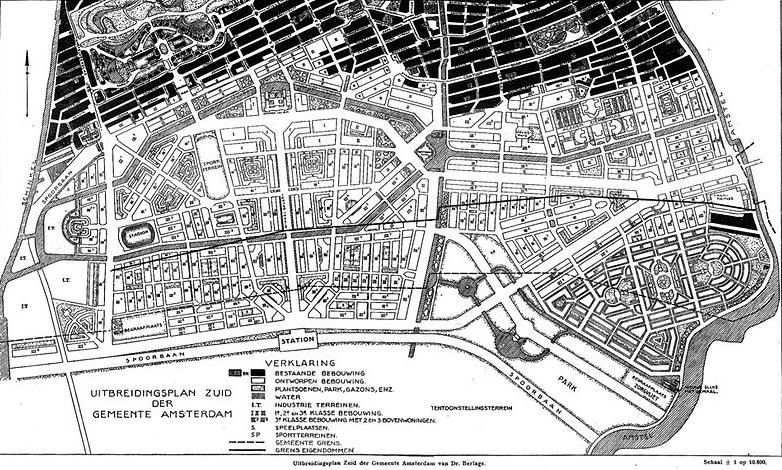

Figure 3. Screenshot, Amsterdam RealTime online, 2002.

Within Amsterdam RealTime, the blur of the technological sublime blurs the performances of the everyday that Polak desires to make transparent. Much of this is due to the insufficiencies of geospatial technologies as they are used for the project. To this end, the Amsterdam RealTime website indicates:

Spots on the ‘map’ which were visited or crossed often, gradually changed in color from white to yellow to red, showing the ‘intensity of use’ of routes or locations. By this logic, the red ‘burn marks’ represent locations which one of the more than 60 participants has visited often or during a longer period of time. The imperfections of GPS localization are consciously visualized by only drawing distinctive lines when a high degree of accuracy was measured. If not, the line is drawn with more fuzziness.47

The blur enters into this locative artistic practice, then, in that it seeks to represent what cannot be represented, much like the technological sublime, with inevitable moments of failure in its attempts to pattern the everyday practices of the participants.

This results in part due to the project’s attempts to avoid, perhaps counterintuitively, the influence of subjectivity within the representation it yields. In an email Polak wrote while formulating the project, she reveals that within the process she discovered “that maps for me always strongly suggested objectivity and authority. I now started to realize that they where [sic] also very much determined by the subjective choices of the cartographer, and by technical, financial, and time limitations.” Indeed, Amsterdam RealTime exemplifies what Polak discusses on technical limitations. This leads her, through the project, to envision an “ideal map” wherein “the worlds depicted by the cartographer is one [sic] of constant change.”48

Through Amsterdam RealTime, Polak navigates this problematic approach by dismissing the singular cartographer in favor of a representative segment of the populace. There is no single cartographer to impose a subjective interpretation on the particular rendering of place provided. But agency within the project is not located within the acts of the subjects themselves. The project’s focus lies in representing everyday practice, but it also ascribes agency to the technologies being employed. The technological apparatus underpinning the project leaves its own mark on the representation through the blurring of the technological sublime. This means that Amsterdam RealTime simultaneously rejects and embraces technological determinism, further situating the project under the aesthetic of the technological sublime.

Moreover, the project adopts a similar drone’s eye view as works of the technological sublime do.49 This has significant ramifications on the project’s continued articulation of being in “RealTime” when the project is now over a decade old. Due to the presence of the drone’s eye view, representing the otherwise unrepresented satellites enabling the project, this articulation merely reaffirms the ubiquity of the satellite presence within discourses of surveillance. It naturalizes a technological terror of sorts, akin to the technological sublime.50

The project’s engagement with the technological sublime makes Amsterdam RealTime’s resonances with discourses of surveillance all the more intriguing. My intent is not to mount a critique of the project as a narrative of surveillance. The consent of the subjects and the frame of everyday practice in the project are critical. Rather, I am intrigued by the aforementioned work that Polak and the Amsterdam RealTime website take in actively distancing the project from such a narration. Polak’s work in this distancing is interesting because of several avenues through which one could read the project through surveillance. While I have already charted some of these avenues, the formal elements of the project itself contrast the Polak’s liberating frame for the project’s participants. Polak chooses, for instance, an ominous color paradigm of black and red and a dark room for the mapping representation.51

While Polak downplays the narrative of surveillance within the project, the broader public considered it a point of contention at the time. When the project was featured on Slashdot, it was posted to “the every-city-could-use-this” section. The project’s website brings up this mention and underscores Slashdot as a site for “tech nerds.” It also heralds the post as a big accomplishment for the project, one considered pivotal to its press attention, alongside a post on Wired.52 The online record of the project, then, attempts to establish a narrative connecting different artifacts from the internet, often considered a non-sequitur space, pairing networks, search results, text descriptions, and advertisements in largely veiled ways to the project.53 But in response to the Slashdot post, the range of titles to the comments – from “thumbs up to big brother” and “real-time vice tracking” to “GPSr fun” and “excellent” – shows how the Slashdot comments on Amsterdam RealTime are rather mixed.54

The Amsterdam RealTime website’s explanation of the process behind the project’s captured information is relevant to this range of reactions. The website details that “[t]he PDA software developed for the project maintains an always-on internet connection to a server at Waag Society and non-stop transmits the resulting coordinates in realtime.”55 Hence, there is consistent data transmission throughout the project. When considered with the applicability of the technological sublime to the project, this consistent presence blurs, rather than traces, mobility through the imprecision of the coordinate tracking involved in the project. In the next section, I connect this failure to the broader exhibition space of Maps of Amsterdam 1866-2000. This exhibition is discussed very little outside of analyses related to Amsterdam RealTime, but it is instrumental in conveying the importance of blueprints to the project.

Contextualizing the Exhibition Space

Taken by itself, the project seems to separate the geographical from the historical in a Kantian manner.56 It ignores, for instance, the role of plans behind key evolutionary city features like the canal ring extensions.57 The city is also often cited for its well-planned web of bicycle paths, even though it is a characteristic of Dutch cities in general.58 While the project’s website mentions this somewhat, its import and historical foundations are in many respects glossed over. Much of this lack of historical context is due to the project’s focus on the everyday actions of its subjects in creating the city. Some of the city’s historical dimensions, however, surface in the larger exhibition space for the project.

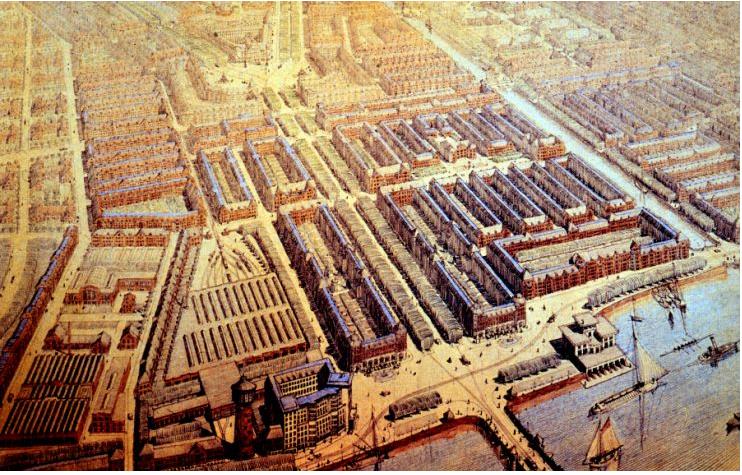

The progression of maps within the Maps of Amsterdam exhibition begins with a map from notable nineteenth-century civil engineer Jacob van Niftrik. The exhibition then showcases other maps covering the history of Amsterdam’s public works and urban design.

Figure 4. Jacob von Niftrik, Niftrik Plan, 1867.

Niftrik devised a mapping draft to overhaul the city’s infrastructure, but his plan was never carried out.59 His failure to convince others to re-imagine the city in accordance with his draft was a complex matter:

In 1867 city engineer van Niftrik unveiled a huge colorful map depicting his plan for the next expansion of Amsterdam. He’d fulfilled his assignment; the city council thanked him and filed his pretty map away. On paper it looked great, both consequent and whole with the original beauty of the town. But it would be too expensive and too systematic, leaving insufficient wrestling room for the entrepreneurs on one side and the social reformers on the other. So the van Niftrik plan became one of many Amsterdams that might have been.60

This is one of many narratives of failure in re-envisioning the city included in the exhibition, which also includes architect H.P Berlage’s plan for a segment of the city.61

Figure 5. H.P. Berlage, Plan South, 1915.

Figure 6. H.P. Berlage, Plan South, Amsterdam Municipal Department for the Preservation and Restoration of Historic Buildings and Sites (bMA).

For his design, known as Plan South, “H.P. Berlage designed an urban extension plan that would include a lot of green. It would contain sleek, modern looking building blocks of affordable social housing” alongside “large squares . . . and waterways.” His first draft was rejected for its expenses, while his second draft was delayed so much due to World War I that a new generation of architects (who rejected what they saw as a restrained, corporate style of planning) took over much of the design.62

I want to recognize the categorization of both of these drafts as plans here. This exhibition, considering the previous discussion on plans, puts a history of failed attempts to reimagine the city on display. The history is one that echoes the complexities of objectivity and precision within Amsterdam RealTime. This would all seem appropriate, since much of our narratives on developing technologies, too, are ones of failure and unintended consequences.

Amsterdam RealTime follows a heritage of radical re-imagining through both the scope of the project and its inclusion in Maps of Amsterdam 1866-2000. The project’s inclusion gives an institutional approval to the project’s place in this historical trajectory. It also recognizes the hope often placed in the blueprints behind the cartographic imaginary and the failure of its blueprints to carry out their visions or to fully imagine the very objectivity they espouse. This supplements the uncanny described here in that the aims of objectivity and precision, ironically, lead to blurring, obfuscating the everyday and the ambulatory.

Conclusion

Locative art projects that have followed Amsterdam RealTime foster similar explorations. An exhibition called Mirrored Sticker from 2013 at the Eyebeam Arts and Technology Center, for instance, designed location-aware stickers with which subjects could tag the city. The exhibition operated as follows:

Participants will post the stickers through the city, creating a temporary mesh network of locally expanded sites. Over a 48-hour period, the installation team will “live code” the map that is generated from the distribution of the stickers. Site Expansion embraces the history of sticker culture—the international tags of graffiti, street art, and skate culture . . . to make [a] very contemporary excursion into site, space, and experimental mapping.63

This sounds very familiar to the aims and appropriations Amsterdam RealTime set a decade prior. The difference is that Mirrored Sticker identifies these aims within those of the smart city, furthering the fraught narratives around surveillance that play out in public discourse. It was part of a symposium comprised of “a group of artists, architects, and media designers whose practice address forms of Internet of Things and Smart Cities.”64 The significance of this extension is that it shows an entry point for the locative uncanny in the future, showing the merit of historicizing the form and paying attention to its many complexities as examined here.

Amsterdam RealTime, though, occupies a unique historical position in the practice of mapping. It renders Amsterdam as a kind of performance—one which is encapsulated by the everyday practices of its inhabitants. At the same time, the project is a system of display, marked by forces beyond that of its presupposed focus and content. Furthermore, the project is a significant historical commentary upon mapping as a genre of display. Several of the mapping projects to which Amsterdam RealTime is juxtaposed in the broader exhibition space emphasize the failure and insufficiency of the cartographic imaginary.

Amsterdam RealTime also occupies a unique position in the emerging history of locative representation in the project’s early adoption of locative artistic techniques and its claim to an ever-present temporality that does not exist. The project, alongside other early locative projects, is now relegated to an uncanny presence. In part, this is due to the transparency of its fraught relationship in the public sphere over the discourses of surveillance prevalent in the digital age. Moreover, in assessing the position of Amsterdam RealTime within the study of locative representation, it is equally crucial to examine the affinities it shares with prior forms of representation and artistic display. Such a focus reveals a historicity behind locative representation, without reemphasizing the technological optimism and uniqueness often purported in the form.

The locative uncanny is built off a variety of appropriations and contradictions pertinent to the contemporary media landscape that I have traced in my analysis of Amsterdam RealTime. It is an aesthetic mode that borrows from graffiti without recognizing an intervention within the public and the private. It borrows from the technological sublime without attempting to represent the very technologies that enable its artistic practice. It pursues the objective and the subjective simultaneously. It approaches its content with such a faith in technology and its precision that it ends up ironically representing a lack of precision that continues being acted out in the present. All of this should make one rightfully question the notion of permissibility evident throughout the project due to the narrative of technological optimism in which the project was (and, in an uncanny sense, remains) framed.

- Lucy A. Suchman, Human Machine Reconfigurations: Plans and Situated Actions, Cambridge University Press (2007), 183. ↩

- “Amsterdam RealTime,” accessed May 5, 2014, http://realtime.waag.org/. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Brian Holmes, “Visiting the Planetarium: Images of the Black World,” in Trevor Paglen (Vienna: Secession, 2010), http://brianholmes.wordpress.com/2011/09/08/visiting-the-planetarium/. ↩

- For more on the broader exhibition, see the following review of the book based on the exhibition: Michèle Jacobs, “Maps of Amsterdam 1866-2000 Review,” accessed May 5, 2014, http://historischhuis.nl/recensiebank/review/show/258. ↩

- Marc Tuters, “Forget Psychogeography: The Object-Turn in Locative Media,” retrieved from http://web.mit.edu/comm-forum/mit7/papers/Tuters_DMI_MIT7.pdf. ↩

- Esther Polak, interview by Annet Dekker, Navigating E-Culture, 61, http://realtime.waag.org/pdf/AnnetDekker_TraversingTheRoute_Navigating07_EN.pdf. ↩

- Ibid, 56. ↩

- Ibid, 61. ↩

- Martijn de Waal, December 1, 2011, “The Ideas and Ideals in Urban Media Theory and Design,” http://www.themobilecity.nl/2011/12/01/the-ideas-and-ideals-in-urban-media-theory-and-design/. ↩

- Jason Farman, “Mobile Interface Theory: Embodied Space and Locative Media” (Routledge, 2012) 52. ↩

- Luca Calderoni, Dario Maio, and Paolo Palmieri, “Location-Aware Mobile Services for a Smart City: Design, Implementation and Deployment,” Journal of Theoretical and Applied Commerce Research 3 (2012), 75. ↩

- Ibid, 85. ↩

- Ibid, 75. ↩

- Esther Polak, e-mail message to friends, Journal for Insiders 1, February 23, 2002, accessed May 5, 2014, retrieved from http://www.beelddiktee.nl/tekst/JournalForInsiders01.pdf. ↩

- Esther Polak, interview by Annet Dekker, 55-56. ↩

- Timothy W. Luke, “Memorializing Mass Murder: The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum” in Museum Politics: Power Plays at the Exhibition (University of Minnesota Press, 2002): 37-64. ↩

- Ned Prutzer, “The Subjects of Subjective Mapping: Locative Art, Critical Theory, and Creative Systems” (Master’s thesis, Georgetown University, 2013). ↩

- Karen O’Rourke, Walking and Mapping: Artists as Cartographers (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2013), 140. ↩

- Esther Polak, interview by Annet Dekker, 56. ↩

- Visconti et al, “Street Art,” 513. ↩

- Sigmund Freud, “The ‘Uncanny,’” in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, vol. 17, trans. and ed. James Strachey et al. (London: Hogarth, 1955), 217-56. ↩

- Elena del Rio, “The Architectural Uncanny: Essays in the Modern Unhomely by Anthony Vidler,” Discourse 15.3 (1993), 178. ↩

- Ibid, 179. ↩

- Anthony Vidler, The Architectural Uncanny: Essays in the Modern Unhomely, The MIT Press (2007), 23; 44. ↩

- Connor McGarrigle, “Locative Histories: Exploring the Continued Influence of Early Locative Media Art,” Media Art Histories 2013, retrieved from http://www.slideshare.net/ConorMcGarrigle/cmcgarrigle-mediaarthistories2013. ↩

- Connor McGarrigle, “The Construction of Locative Situations: Locative Media and the Situationist International, Recuperation or Redux?” Digital Creativity 21.1 (2010), 57. ↩

- See www.biomapping.net. ↩

- McGarrigle, 57. ↩

- Erkki Huhtamo, “Messages on the Wall: An Archaeology of Public Media Display,” in Urban Screen Reader (Institute of Networked Cultures, 2009): 15. ↩

- Chris Perkins, “Performative and Embodied Mapping,” International Encyclopedia of Human Geography. ↩

- Marilyn Adler Papayanis, “Sex and the Revanchist City: Zoning Out Pornography in New York,” Enivronment and Planning D: Society and Space 18 (2000): 350-351. ↩

- Alison Sant, “Redefining the Basemap,” intelligent agent 6, accessed May 5, 2014. ↩

- Michel de Certeau, “General Introduction,” The Practice of Everyday Life, http://www.ubu.com/papers/de_certeau.html. ↩

- Esther Polak, interview by Annet Dekker, 54. ↩

- Ibid, 60. ↩

- Ibid, 59. ↩

- Robert Drew, “Graffiti as Public and Private Art,” in On the Margins of Art Worlds (Westview Press, 1995): 231. ↩

- Ibid, 236; 245. ↩

- Luca M. Visconti, John F. Sherry Jr., Stefania Borghini, and Laurel Anderson, “Street Art, Sweet Art? Reclaiming the ‘Public’ in Public Place,” Journal of Consumer Research 3 (2010): 513. ↩

- Marc Tuters and Kazys Varnelis, “Beyond Locative Media: Giving Shape to the Internet of Things,” Leonardo 39 (2006), retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20206268. ↩

- Timothy Cresswell, In Place Out of Place (University of Minnesota Press, 1996), 37-50. ↩

- Ibid, 58-61. ↩

- Ethan Todras-Whitehill, “The Web Behind the Scrawl,” New York Times, May 4, 2005, accessed May 5, 2014, http://www.nytimes.com/2005/05/04/technology/techspecial/04ethan.html?_r=1&. ↩

- Holmes, “Visiting the Planetarium.” ↩

- “Amsterdam RealTime.” ↩

- Esther Polak, e-mail message to friends. ↩

- Holmes, “Visiting the Planetarium.” ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- “Amsterdam RealTime.” ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Johanna Drucker, “Humanities Approaches to Interface Theory,” Culture Machine Vol. 12 (2011): 1-20. ↩

- “Real Time Collaborative Mapmaking,” last modified December 2, 2002, http://slashdot.org/story/02/12/02/1922241/real-time-collaborative-mapmaking. ↩

- “Amsterdam RealTime.” ↩

- See David Harvey, Cosmopolitanism and the Geographies of Freedom, New York: Columbia University Press, 2009. ↩

- See Mark Minkjan, “Amsterdam’s Morphology, A History,” retrieved from http://citybreaths.com/post/40011703127/amsterdam-morphology-a-history. ↩

- Renate van der Zee, “How Amsterdam Became the Bicycle Capital of the World,” The Guardian, May 5, 2015, accessed July 5, 2015, retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/cities/2015/may/05/amsterdam-bicycle-capital-world-transport-cycling-kindermoord. ↩

- Michèle Jacobs, “Maps of Amsterdam 1866-2000 Review.” ↩

- “How Amsterdam Got Here,” accessed May 5, 2014, http://www.postwar.nl/amsterdam/howams_pg/howamsterdamgothere.html. ↩

- Jacobs, “Maps of Amsterdam 1866-2000 Review.” ↩

- “Plan South,” http://www.amsterdamtourism.net/plan_south.html. ↩

- “Site Expansion: Locative Art,” last modified August 12, 2013, http://www.cityasplatform.org/portfolio/site-expansion-locative-art/. ↩

- Ibid. ↩