“I went to the photographer’s show as to a police investigation, to learn at last what I no longer knew about myself.” – Roland Barthes.1

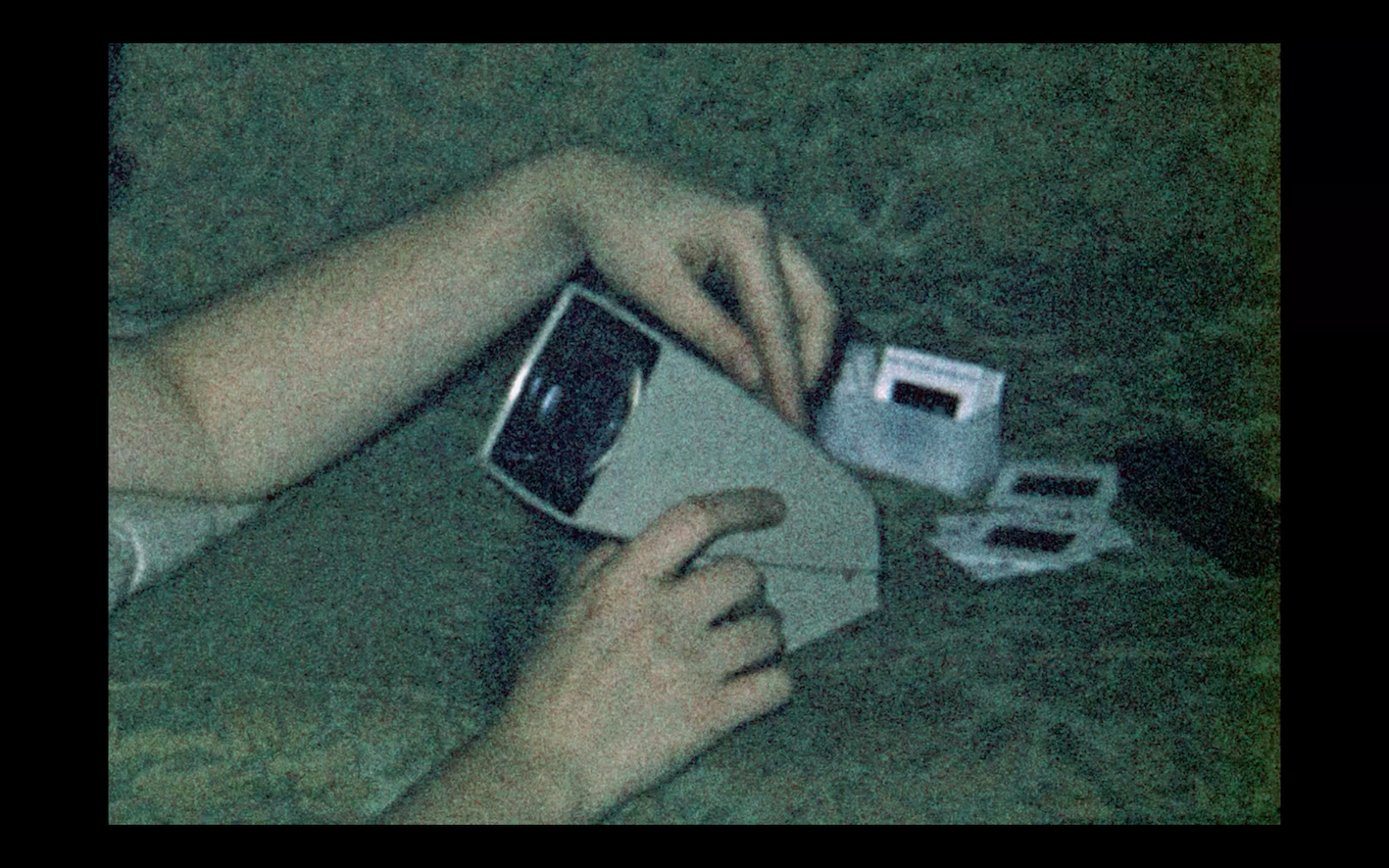

After an estrangement of nearly forty years, I have recently reconnected with my late father’s extended family. This video is the first step in an exploration of this process through visual autoethnography. I have been immersing myself in the large photographic archive of my equally large family, working with hundreds of family slides and photographs. I digitize slides, removing the visual remnants of dust, fingerprints, and the wear and tear of years gone by. I edit and tag and save metadata to the files I create.

Along the way, I engage in a sort of personal photo-elicitation—are memories stored in these images? Can I access them? What do the photographs mean to me? Where am I pricked by Barthes’ punctum?

The photographs both represent and trigger memories; they also challenge and sometimes fully contradict the things that I think I know. Further, they offer the opportunity to imagine alternate histories, multiplying personal timelines. I mediate on these images as I edit them, looking for my own real past and imagining the past that wasn’t. Through this work, I also restore myself: making a place for myself in the visual record of a family from which I had been long absent. Although I do look eagerly for pictures of myself as a child, it is not these images that solidify my new position in the family. As important as these visual artifacts are to me, their true value is in the social context of how they are used—the rituals of photographic spectatorship. We bond through a sing-song recitation of Barthes’ photographic essence: that has been. That’s me, that’s you, there he is, and oh, do you remember that tree? In the end, such declarations are not about the photographs themselves as much as they are about the relationships that are built while looking.

- Barthes, Roland, Camera lucida: Reflections on photography (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981), 85. ↩