Reviewed by Kirin Wachter-Grene

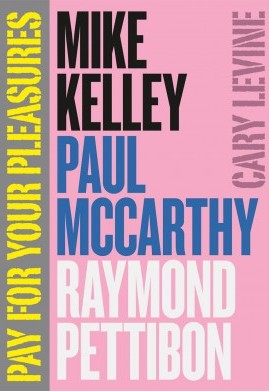

Cary Levine. Pay For Your Pleasures: Mike Kelley, Paul McCarthy, Raymond Pettibon. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 2013. Hardcover. 211 pp.

Cary Levine’s first book, Pay For Your Pleasures: Mike Kelley, Paul McCarthy, Raymond Pettibon, uses three of America’s most transgressive artists to reconsider the concept of “transgressive” art. The first book to offer a sustained study of these Los Angeles artists, “bad boys” entering the art world in the 1970s and rising to prominence in the 1980s and 1990s, is, on one hand, a deeply researched biographical account of Kelley, McCarthy, and Pettibon, respectively, reinforced by interviews between author and artist. Levine places their considerable bodies of work, through the 1990s, in sociopolitical context and considers the artists both individually and together, linking their work through critical frames of gender, sex, and adolescence. His book is also one of the first to engage with all three artists’ involvement in underground music scenes, the effect such sonic subcultures had on their work, and the themes and methods running across and through the sound and the visual. Finally, it is a study so imbued with Levine’s enthusiasm for his subject matter and so tightly written that the prose crackles with electricity, with his acerbic wit. One gets the sense that Levine revels in exposing the banality and absurdity of all that America holds sacred as much as his subjects do. As such, Pay for Your Pleasures feels like the kind of titillating conversation one has with a kindred sardonic spirit behind closed doors, as much as it reads as a rigorously researched, comprehensive, and historically situated contribution to studies of visual culture and cultural criticism. Indeed, it is quite an accomplishment, as well as a compelling read.

Pay For Your Pleasures begins by discussing the study’s eponymous work: Kelley’s 1988 Pay For Your Pleasure, an installation consisting of a hallway draped in floor-to-ceiling painted banners, each displaying a portrait of a famous public figure and quotes in which they wax poetic about artistic freedom. The banners include Paolo Veronese and his statement, “We painters claim the license that poets and madmen claim”; Piet Mondrian and his assessment, “I think the destructive element is too much neglected in art”; and Charles Baudelaire and his challenge, “If rape or arson, poison or the knife, has wove no pleasing patterns in the stuff of this drab canvas we accept as life—it is because we are not bold enough.” At the end of the hallway hangs a painting by a convicted criminal that changes depending on the installation’s geographic location. 1988’s exhibition at the University of Chicago featured a clown painted by the city’s infamous serial killer John Wayne Gacy. Reaching it, the audience is ensnared, surrounded by idealist rhetoric while contending with “the handiwork of a psychopath,” caught in the uncomfortable space where theory and practice meet (2).

Kelley’s installation is central to Levine’s study because Levine’s analysis of transgression, much like Pay For Your Pleasure, is antithetical to the banners’ tired platitudes. Levine’s project is not about perpetuating a celebration of artistic lawlessness and its supposed liberatory potential. In fact, as Levine argues, through their challenges to dominant concepts of transgression, Kelley, McCarthy, and Pettibon are simultaneously transgressive and “anti-transgressive” (6). Kelley’s Pay For Your Pleasure, for example, succeeds in placing the onus of affective response on the viewer (16), uncomfortably requiring confrontation with his or her culturally constructed beliefs and cherished ideals. Most importantly, the work forces the viewer “to not only acknowledge but also take responsibility for a cultural legacy that validates their own perverse curiosities” (2).

Thus Levine, through his convincing assessment of the artists’ methods, reads transgression as a social experiment. “Rather than preach or simply shock,” he writes, Kelley, McCarthy, and Pettibon “set traps, ensnaring the viewer in discomforting and often irresolvable situations—psychological, moral, and aesthetic” (9). As he establishes, these artists make masterful use of the grotesque, of obscenity, absurdity, self-abuse, moral and ideological ambiguity, confusion, perversion, and crass humor to accomplish this entrapment. For instance, in his analyses of McCarthy’s performances of self-abuse, such as Hot Dog (1974), Sailor’s Meat (1975), and My Doctor (1978), Levine suggests that McCarthy aims to disrupt not only the art-viewing experience, but also “socialized experience as a whole” (31). In much of McCarthy’s work substances such as ketchup and margarine, ground beef and moisturizing cream become blood and lubricant, fecal matter and semen, respectively (3). Thus Levine focuses on the artist’s tendency to provide an “all-out assault on categories” (3) achieved through his conflation of comedy and disgust, absurdity and brutality, stupidity and psychological disturbances. McCarthy perverts conventions as “a form of research” (3); his unfolding scenes, in which such innocent materials are re-contextualized into indecent scenarios of sexualized violence and violent sexuality, make it impossible to settle on any one interpretation (3). As such, the work “collapse[s] distinctions between reality and artifice: [McCarthy’s] self abuse [is] both absurd and dangerous, dramatized and concrete…viewers [are] both witness and accessories” (30). And the inability to categorize the performances and one’s affective responses are “arguably the works greatest offense” (32).

Levine is an adept visual analyst, able to seamlessly move between and across genres from instillation to performance to illustration. Furthermore, his prose is powerful and dynamic, his structure clear and effective. At times his argument is so razor-focused and hard-driving that he fails to consider alternate perspectives and counter-arguments. For instance, reading his analyses of Pettibon, in which he argues the primary transgressive thrust of the work is its biting satiric parodies of “radical” politics and their claims to originality and authenticity (73), one is left with the erroneous impression that Pettibon has no female audience because Levine’s assessment of the work and of its hypothetical viewer is so male-centric.

Yet perhaps knowing his study can come off to the skeptical reader as unduly laudatory, Levine is steadfast in his commitment to historicizing the work. He does so as a means to firmly establish its import to its cultural moment and argue how it is informed by that contemporaneity, as well as testify to the stakes of re-conceptualizing transgression in the manners these artists achieve. For instance, as all three are responding to post-1960s politics, often by “pissing into the ideological wind” on both the right and the left (17), Levine places their work in the context of Senator Jesse Helms’s 1980s crusade against the National Endowment of the Arts to better comprehend how it spoke to debates about censorship and utopian sentiment. Through their disenchanted points of view (bred of their respective backgrounds, influences, and involvements) Kelley, McCarthy, and Pettibon “ravage convictions on the Left and the Right, treating them as mutually reinforcing sides of the same coin” and continually ensnare viewers in this psychological and moral conundrum (9). What Levine ultimately suggests is that the work of these artists purposefully problematizes dominant readings and political stances and in so doing opens a discourse of “anti-utopian consciousness raising” (16) that suggests, “the only possible freedom is freedom from the illusion of freedom” (17). Theirs is brave work, often difficult to stomach. Its value, Levine argues, is in blurring interpretive frameworks to implicate and challenge not only the art censor but also the art appreciator.