Reviewed by Lyle Jeremy Rubin

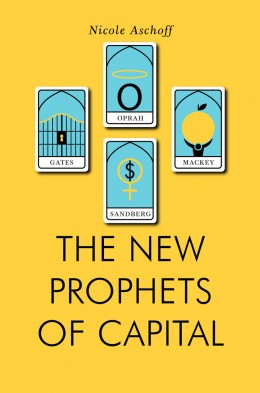

Nicole Aschoff. The New Prophets of Capital. New York: Verso. 2015. Paperback. 160 pp.

The only thing more treacherous than a satanic minion is a false idol. For radical critics of society, the latter functions as a craftier version of the former. While the social Darwinist on Wall Street isn’t doing anyone favors, it’s the “socially conscious” reformer who’s really mucking things up, especially if that reformer is a tech billionaire who shrouds her Protestant work ethic in a wardrobe of defiant feminism (i.e., the Chief Operating Officer of Facebook, Sheryl Sandberg), an entrepreneurial grocer who sells his free market fundamentalism as “organic,” (i.e., the CEO of Whole Foods Market, John Mackey), a rags-to-riches entertainer who preaches the bootstrapping gospel in a language of compassion and warmth (i.e., Oprah Winfrey), or a multibillionaire power couple attempting to save the world by showering various sectors of the global economy with the remains of their pocketbook (i.e., Bill and Melinda Gates). As the sociologist Nicole Aschoff explains in The New Prophets of Capital, this quintet embodies late capitalist “charisma” to a T. The fact that their methods of accumulation are accompanied by self-styled critiques of capitalism makes their charisma all the more alluring to anyone short on cash—that is to say, most of us.

What makes these evangelists truly threatening, according to Aschoff, is the means by which they convert anti-capitalist potentialities into capitalist products, rhetoric, or methodologies that reinforce the status-quo. Take Sandberg, for example. While her exposure of gender inequality in the workforce is genuine and welcome, she offers nothing for female workers but a self-serving admonition to work harder. In the process, she redefines feminism, in Aschoff’s terms, as “self actualization through self-exploitation.” One of Sandberg’s proud examples of a woman “having it all” is Jen Holleran, a mother of two infant twins, who managed Mark Zuckerberg’s $100-million pet project to better the performance metrics of the Newark Public Schools. This sounds like a story with a happy ending, but for the residents of Newark, the corporate education reform agenda has proven an unmitigated disaster, and Mrs. Holleran’s mandates have rendered the life of the district’s majority female teachers a living hell. Aschoff does a fine job sketching this account by pinpointing how an otherwise typical union-busting enterprise has been wrapped in the banner of an allegedly feminist and worker-friendly politics.

John Mackey and his philosophy of “conscious capitalism” follow a similar narrative. Like Sandberg, the founder of Whole Foods doesn’t believe the problem is capitalism but rather the demographic makeup of the capitalists themselves. Whereas the tech titan is convinced more women are needed in corporate America, Mackey thinks we need more nice folks like him behind the wheel. As a right-wing libertarian, he dismisses government regulation and union power as failed relics of the past. The future lies with socially conscious enterprises like his own, and that means more socially conscious bosses like him. But while it’s true his company treats its workers and the environment better than many of its competitors, Aschoff concedes, it is equally true that his philosophy can’t be scaled up, because in the long haul, it’s virtually impossible for a firm to maintain profits while also maintaining socially conscious standards. This is why there are a slew of new socially conscious firms but hardly any old ones, and why, under Mackey’s arrangement, employees are forever at the mercy of their employer’s good will and the good macroeconomic vibes of the moment. And even now, as Aschoff reveals, the business exploits prison labor for the processing of its artisanal food. Again, we are confronted with an ostensibly humane business model that crumbles at the slightest hint of critical pressure.

If Sandberg and Mackey call for a change of mindset or personnel at the top, Oprah seeks to comfort the aspiring classes. She taps into mass hopelessness and alienation, often in intimate and moving terms, to market a familiar product. Aschoff reminds the reader that nineteenth-century novelist Horatio Alger peddled tales of poor folk making it to the middle class, not without considerable luck. Oprah, in contrast, promises emotional and material abundance for anyone willing to exhibit the right measure of grit and determination, misfortune be damned. Drawing further parallels with the first Gilded Age, Aschoff also notes that Oprah’s eagerness to convert problems of employment and opportunity into individual trials to be overcome by shifts in attitude is reminiscent of the late nineteenth century Mind Cure movement, whose mythology of total autonomy and agency fits comfortably into the neoliberal present.

While the profiles on Sandberg, Mackey, and Oprah are rich in detail and insight, Aschoff’s chapter on the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation really brings the theoretical critique to the fore. After acknowledging the couple’s achievements in fortifying the vaccination markets in poor nations (literally by throwing billions of dollars at these emerging markets), she proceeds to analyze their philanthropic project. The Gates Foundation’s desire to introduce more markets reinforces structural inequities even if it closes in on inequities at the margin, which adds up to a profoundly undemocratic initiative since it provides no voice or agency for the people it is intent on helping. Instead, it leaves the world’s most vulnerable citizens at the mercy of plutocratic generosity while simultaneously redirecting anti-status quo energies away from collective forms of resistance and struggle and toward attitudes of quiescence and gratitude. The same could be said for the Foundation’s interventions into public education, where similar dynamics have emerged. In a disturbing passage, Aschoff describes how Gates-sponsored KIPP charter schools have adopted the “learned helplessness” theory of the psychologist Margin Seligman—the same theory deployed by the CIA to hone their torture techniques at Guantánamo Bay. She also depicts misbehaving students being forced to wear signs that read “MISCREANT” or “CRETIN.” No wonder “only 40 percent of students who start at KIPP schools finish.” Once more, we see acts of noblesse oblige eventuating in the sustainment (or even intensification) of the very unequal relationships they are trying to overcome.

In between Aschoff’s elegant portraits and autopsies, one awaits unavailingly for her to define her terms. While it is clear liberal capitalism counts as the problem, it is unclear what this means, and what qualifies as the feasible alternative. During her discussion of John Mackey and the limits to growth, for example, the reader is left wondering where green Keynesianism, dematerialized growth, or a steady state economy fit into Aschoff’s somewhat stark dichotomy between liberal capitalism and democratic socialism. Nevertheless, the book’s larger point is made with grace and force. The common thread running through the stories of all five characters is their faith in private enterprise over collective action. There is no room in their visions for labor unions, democratic workplaces and ownership, public banks, social movements, mass activism, community stabilization measures, third party politics, or much politics at all for that matter. A just society, they believe, must be forged by the good will of the ruling class and the hard work of everyone else. And yet, Aschoff and her allies aren’t the only ones objecting. Her five subjects would be well advised to listen to the flagship publication of free market boosterism, The Economist. In its “Special Report: Corporate social responsibility” (Dec 14, 2002), the magazine took a stand that has remained part of its credo ever since:

“[T]he corporate social responsibility movement has got it all the wrong way around. It tends to look for social goods—better housing, better schools, a cleaner environment—and then seeks ways to force companies to provide them. It might do better to look at the things that the private sector does not deliver, and then get governments to fill the gaps…[Companies] are not here to build a fairer society. That is the job of government.”

So there you have it, issued directly from the devil’s lair: The new prophets of capital should stick to their profits. It’s up to the rest of us to make the world a better place.