By Greta Olson

Having just begun its sixth season, Showtime’s spy thriller Homeland was greeted by television critics as a new type of critical post-‘9/11’ text when it premiered to great fanfare in 2011. The series has documented the United States’ sense of its continuous vulnerability to terrorist threats as well as the country’s ongoing obsession with security in the post-attack era. In this sense Homeland bears similarities with earlier ‘9/11’ texts such as the series 24 and the film World Trade Center. Nonetheless, the series appeared to provide critique of some post-‘9/11’ anti-terrorist policies and incursions on civil rights. The novelty or, as I will argue, the post-ness of Homeland as compared to dominant ‘9/11’ texts like 24 or the film Zero Dark Thirty was demonstrated by the series’ comparatively critical depictions of torture as a form of gathering intelligence. Rather than effective, torture was shown to be inferior to more humane and psychologically refined forms of learning about security risks. For instance, in “The Weekend” (SE 01 E07), CIA Division Chief Saul Berenson convinces Aileen, a young American woman terrorist, to confide in him by building up a relationship of trust in which he connects with her through shared experiences of exclusion. By creating a relationship based on mutual sympathy rather than through torture, Saul is able to convince the woman to talk.

Furthermore, Homeland appeared to offer more differentiated representations of Muslim individuals than other fictionalizations of terrorism had done, and it featured a woman protagonist versus the majority of post-attack counterterrorist representations. For all of the ambivalence of her character, anti-terrorist CIA operative Carrie Mathison provided a seeming antidote to the multiplicity of hyper-masculine heroes who had peopled dominant ‘9/11’ texts by, for instance, displaying knowledge of and respect for Islam. In scenes from “Crossfire” (SE 01 E09), she is shown having covered her hair and having removed her shoes before entering a mosque, greeting its Imam politely in Arabic, and sincerely apologizing for what have been her FBI colleagues’ violent actions there.1

Homeland appeared then to indicate that the US had entered into what might be considered “a post-‘9/11’” period featuring more critical representations of security measures and marked by an increased self-consciousness not only about torture but also about the use of drones in targeted killings and enhanced surveillance measures, as well as an awareness of the public relation aspects of anti-terrorist measures. Post-‘9/11’ fictional texts, as I call them, function to critique dominant ‘9/11’ tropes by questioning the strategy of revenge and the utility and effectiveness of security measures in the post-attack period such as torture, rendition, and extralegal incarceration. By treating the events of 11 September 2001 more self-reflexively than their predecessors did, these post-‘9/11’ texts interrogate the political and medial discourse of victimization and necessary retaliation that followed after the attacks and the counterterrorist strategies that went along with this discourse.2

Homeland conveys a self-conscious ambivalence about anti-terrorist security measures in the post-‘9/11’ era. This self-consciousness is underlined by several interconnected formal devices. The first of these is the employment of what I am going to call visual unreliability; this representational technique is most prominently displayed in the series’ opening credits, which mimic the instability of the central protagonist’s mental state. This formally inscribed unreliability, a term to which I shall return, is also carried out on a cinematographic level – in a scene from “The Weekend” (SE 01 E07), and in the series of sequential shots in the drone sequence from “Crossfire” (SE 01 E09) – in which the viewer no longer knows whose perspective to trust. My argument is that the series’ cinematography, particularly its juxtaposition of shots and visual editing, contributes on a formal level to the story elements that are intended to evoke doubt as to the efficacy and appropriateness of violent security measures in the post-‘9/11’ era.

To a certain degree many of these formal devices are typical of what has alternatively been called the new quality or post-network television series. The former term functions to highlight features of recent (post-1990s) television series that have characteristics once thought to be exclusive to film; quality television also includes the evaluation that current television is “better” and more worthy of critical scrutiny than old school television. Features of so-called quality television include high-budget filming on location rather than in studios, the lack of commercial breaks (in cable shows), newly complex and non-episodic narrative structures, and an exploration of topics and issues that, during the network era of television, fell prey to censorship.3 The latter term, post-network television, by contrast, underscores new means of transmitting televisual material and new types of viewing practices and conditions: these include streaming onto laptops and handheld devices, thus taking television out of the traditionally feminized space of the home, and the generalized use of High Definition Wide Screen televisions that reproduce the visual aesthetics of the movie theater.4 Whatever one chooses to call it, television has fundamentally changed, whether in its network or cable forms, from the formulaic half or full hour, laugh-track and commercial-break-filled fare of this author’s childhood in the 1970s to something else altogether.

Figure 1: “Pilot” (S01 E01), Homeland (2011 – present). Claire Danes, scene still. 20th Television, 2012. Author’s screenshot.

Torture Chic and Dominant ‘9/11’ Representations

I define dominant ‘9/11’ representations as texts that are characterized by retaliatory attitudes towards putative terrorists, whether they are fictional or not; such texts contributed to post-attack practices, such as curtailing civil rights, after the passage of the Patriot Act in 2001, and to violating human rights agreements and laws through extrajudicial rendition, the quasi-legalization of so-called enhanced interrogation techniques, and the use of drones to gather intelligence and to carry out targeted killings. Dominant ‘9/11’ texts impose a narrow code of gendered and nationalistic representational strategies on their subject matter: they favor first-person tales of suffering and heroic loss, as in films such as Paul Greengrass’s United 93 (2006) and Oliver Stone’s World Trade Center (2006), and the valiant responses to the attacks by their male protagonists function to underline US American resilience and unity.5 These representations depict the attacks as a horrific and historical caesura such that any and all aggressive US responses to them appear to be highly justified. Moreover, dominant ‘9/11’ texts effect a binary reification of supposedly opposed gender roles: they foreground the physical strength of masculine first-responders, whereas allegedly helpless Muslim and Arab women or the vulnerable motherland are presented as in need of protection by hyper-masculine American soldiers.6

In these dominant representations, the United States’ already supposedly exceptional status in world politics and history is further ‘verified,’ and the extraordinarily democratic and meritocratic qualities of the country are emphasized. An example of this is provided by then President Bush’s address to the nation on 12 September 2001, in which he speaks about the country’s having been targeted because “we’re the brightest beacon for freedom and opportunity in the world.”7 Dominant representations also function to displace traditional forms of American racism, primarily directed towards those considered Black, onto Muslims, Arabs, and those who were mistaken as such.8 Homeland’s apparent differences from this type of dominant representation led critics in particular to brand it an “anti-24”. 24 (2001-2010, 2014), it may be recalled, in its first iteration from 2001 until 2010, featured a virtual celebration of scenes depicting torture as an effective anti-terrorist practice and thereby functioned to support the politics of the Bush-era War on Terror.

Figure 2: “Day 7: 8:00 a.m. – 9:00 a.m.” (S07 E01), 24 (2001 – 2014). Kiefer Sutherland, scene still. 20th Television, 2009. Author’s screenshot.

24’s surplus of terror scenes arguably gave its audience a sense of retributive enjoyment. As New Yorker critic Emily Nussbaum wrote in 2011: “On ‘24,’ the torture scenes were the sex scenes. They were part of what made the show so repellent. Without ever acknowledging it, ‘24’ harnessed the nudity and emotional exposure of torture to arouse the audience, to merge our bloodlust with something libidinal.”9

The series suggested that only Jack Bauer, an operative in a fictional Counter Terrorist Unit (CTU) based in Los Angeles, could and would do ‘whatever it takes,’ as the protagonist repeatedly states, to save the United States from terrorist threats from Iraqi jihadists and local extremists. Doing ‘whatever it takes’ entails operating outside of the law to obtain information and subverting attacks by torturing suspects. In response to its American and Western audience’s generalized sense of fear, 24’s surplus of torture scenes grew in number even as the series faced repeated criticism for its glorification of extreme anti-terrorist violence. Arguably, such torture scenes were intended to give viewers a sense of pleasure in ‘punishing’ terrorists that functioned to contain anxieties about future attacks. Most importantly, the aesthetics of 24, which were highly praised for their innovativeness, added to the audience’s sense of imminent threat as well as to the seeming urgency and topicality of the series’ subject matter. The need for constant vigilant surveillance and extreme security measures was conveyed not only through Jack’s torturing terrorist suspects in order to halt the detonation of a nuclear bomb in Los Angeles (Season 2) or the assassination of the President (Season 1). Emphasizing a new post-attack economy of visibility, 24’s CTU features large flat screens through which intelligence is gathered and evaluated, suggesting the goal of total transparency and constant surveillance. The employment of real-time action, in which the discourse level of storytelling matches the plot level of action and each season represents a twenty-four hour day, with every episode an hour within that day, and the ever visible digital clock that continues to tick even during commercial breaks are all features that hammer home a sense of threat and merely provisional safety.

The series’ emphasis on the need for constant surveillance cohered with the Bush-era practice of placing the nation under constant the series’ stress on the, urgent terrorist alerts. The use of split screens to display simultaneous plot threads, and constant race against the ticking clock, often featured prominently in the middle of several split screens, as in the screen shot from Season 7, Episode 24 pictured below, added to viewers’ sense of being with Jack Bauer in a desperate race for time.

Figure 3: “Day 7: 8:00 a.m. – 9:00 a.m.” (S07 E01), 24 (2001 – 2014). Split screen, scene still. 20th Television, 2009. Author’s screenshot.

Such formal means suggested that the constant terrorist threat had to be combated with acts of extreme proactive violence. When Jack, as he so often did, exercised his need to torture a suspect, torture was effective, conducted rapidly, and resulted in pertinent information being garnered. Most frequently, 24 justified Jack Bauer’s use of torture by employing time-bomb scenarios: if terrorist X was not tortured immediately and made to give up information about the bomb’s location, then eight million people in Los Angeles would die in a nuclear explosion. This scenario, which was repeated through numerous iterations, even justified Jack’s forcing of one suspect to watch a film in which first one of his sons is shot and then a second is threatened. In this, a shorthand version of Utilitarian reasoning was abused to suggest that the immediate suffering of the one perpetrator was eminently justified given the future benefit to many. The pro-torture sensibility that 24 projected reflected a larger US American sense that the use of torture as a form of security was justified given the extremity of the United States’ predicament. Writing for the centrist news magazine Newsweek in 2001, Jonathan Alter stated that “we need to keep an open mind about certain measures to fight terrorism, like court-sanctioned psychological interrogation. And we’ll have to think about transferring some suspects to our less squeamish allies, even if that’s hypocritical. Nobody said that this was going to be pretty.”10 As was repeatedly commented upon, series such as 24 contributed to pro-torture sensibilities and practices. Jane Mayer’s seminal New Yorker article from 2007 documented how instructors at West Point attested that they found it difficult to teach proper intelligence gathering methods to future officers headed to Iraq, given the cultural cache of 24. As one instructor reported: “The kids see it, and say, ‘If torture is wrong, what about ‘24”?’” He continued, “The disturbing thing is that although torture may cause Jack Bauer some angst, it is always the patriotic thing to do.”11

And 24 did not just appeal to the sensibility of young West Point cadets. At a law conference in Ottawa, the late Supreme Court Justice Scalia contested that Jack Bauer’s use of torture to save Los Angeles would not receive a verdict of guilty in any trial by jury: “Are you going to convict Jack Bauer? […] Say that criminal law is against him? ‘You have the right to a jury trial?’ Is any jury going to convict Jack Bauer?”12 The obvious answer to Scalia’s mind was ‘no.’ Similarly, legal expert Alan Dershowitz advocated the need for terror warrants as in Israel so as to regularize its practice (2004).13 The fictional 24 then became a vehicle for extra-textual arguments about the legitimacy of torture and other violent security measures.

24 appeared to fulfill a cultural desire to imagine scenarios even worse than the now iconic images of the September 2001 attacks and to fantasize about how they might be met with heroic extra-legal violence: “As the nations of the world continue to recuperate and recover from the horror of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the suicide bombers in Israel, and the bombings in London in July 2005, 24 plays out nightmarish terror scenarios that dare us to imagine the very worst – that the terrorists are out there, in our cities and near our homes, armed and plotting and waiting to strike.”14 As with its presentation of a highly ethical black president during its first seasons, 24 has often been described as not only reflecting on prevailing US American sensibilities but also anticipating future ones like the election of Barack Obama in 2008 and the intensification of violent anti-terrorist practices: “this series revealed, albeit fictionally, a massive shift in ethical thinking, and action, by the US government in the aftermath of ‘9/11’ and those revelations came via TV series long before they came through the mainstream news media.”15 In summary, 24’s highly effective visual aesthetics contributed to the series’ plot level contestation that terrorism was ubiquitous and omnipresent and had to be combated by whatever means. The frequent references to the show’s extra-textual effects in justifying torture as a counterterrorist practice described above demonstrate how its story and discourse level representations of terrorism influenced general attitudes about national security.16

24 was not alone in legitimizing scenes of anti-terrorist, extra-judicial torture. The series Alias and Lost both presented multiple, politically-muddied torture scenes as did other cultural representations such as John Galliano’s 2008 Men’s Collection, which was inspired by Abu Ghraib, or the “State of Emergency” September 2006 Vogue photo shoot, both of which may be said to have constituted a kind of torture chic. More wide-ranging cultural commentaries suggest that series concerning illegal actions such as The Sopranos and Dexter dramatized a post-attack state of paranoia and what was seen as the need to operate outside of the law in order to make oneself and one’s family secure in the post-‘9/11’ era.17

In contrast to these series, Homeland at least initially appeared to dramatize US American preoccupations with terrorist attacks and anxieties about security quite differently. Its self-consciousness about the appropriateness of violent security measures begins on the visual level with its artistic credits. They show the acculturation of CIA Operations Officer Carrie Mathison into a permanent state of paranoia that mirrors America’s post-attack collective psyche. The audience witnesses a series of rough-cut flashbacks to Carrie’s childhood, cuts that arguably work against an illusion of mimetic immersion in the series’ fictional world. Against the aesthetics and more usual practice of continuity editing, these rough cuts render the process of switching from one shot to another quite visible, noticeable, and jarring.

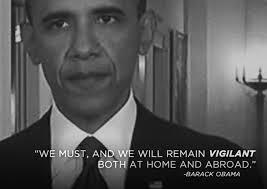

Carrie’s psychic history is then revealed in nearly ninety seconds of credits that also picture a nation’s increasing sense of vulnerability. Over-the-shoulder, point-of-view shots, often in dissolves, first show the sleeping and then the waking child Carrie watching television as Reagan announces US anti-terrorist air strikes in Libya in 1986, George H. W. Bush condemns the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990, Clinton announces the terrorist attack on the USS Cole in 2000, and Colin Powell makes his presentation to the UN Security Council in 2003. Subsequently, handheld video footage shows the aftermath of the 11 September attacks in Manhattan. Finally, Barack Obama is pictured first upside down, then right side up, and upside down again in footage announcing the killing of Osama bin Laden in May 2011. Within the course of the accompanying jazz soundtrack, we also hear a commentator reporting on the hijacking and bombing of Pan Am Flight 73 in 1986.

Figure 4: “Opening Credits, Season 1,” Homeland (2011 – present). Barack Obama, scene still. 20th Television, 2012. Author’s screenshot.

The credits make visible the televisionization of terrorist threats since the 1980s. At the same time, interspersed footage from handheld film clips from the aftermath of the 11 September attacks invoke collective visual memories of endless loops of footage of the airplanes crashing into the Twin Towers, the ensuing mayhem on the streets, and people running away from downtown Manhattan, and the towers’ collapse. As Eric Gould writes of this editing, “rough cuts […] represent the anxiety of Carrie’s job. She’s a loose metaphor for the country at large, at once steeped in the mundane banal of the everyday, and wired like a cat at the prospect of swift mayhem and violence.”18 The imagery presented in the credits represents, then, not only Carrie’s individual visual and auditory memory of a life punctuated by threats of terrorism but also that of her contemporaries, the probable viewers of the series. Carrie’s training to be constantly vigilant about terrorist threats is highlighted by images of her sleeping and batting eyes as a child and an adult, signally the processing of her levels of consciousness. The audience sees her, over time, learning how and why to be in a perpetual state of insecurity regarding the threat of terrorist attacks.

Within the credit sequence, a second narrative stand is interspersed with the first more prominent one about Carrie’s acculturation into security paranoia. This second narrative is conveyed visually through a series of still images in color and sepia of the child and then the adult Carrie, pictured in a garden maze with a uniformed Nicholas Brody on the other side of the topiary maze’s wall. The maze images invoke the myth of the half bull, half man Minotaur from Greek mythology who lived in a labyrinth and fed on maidens and youths who were sacrificed to him in the maze. In a series of photographs, Carrie is shown wearing a lion mask as she stands in the maze, whereas Brody is in uniform and unmasked.19 These images of hunter and hunted in a labyrinth render unclear what Carrie’s role in the first season of Homeland is going to be: is she to play the righteous pursuer of a covert terrorist, the POW Marine Sergeant Nicholas Brody, as is suggested by her lion mask? Or, is she in fact more akin to the monstrous Minotaur, a vicious monster who figuratively hunts – illegally spies on – the innocent without reason, Brody and his family? Brody’s possible innocence from suspicion is alluded to visually in photographs showing him as a sweet-faced child in front of his piano. The credits’ juxtaposition of images of its protagonists’ childhood faces with severe images of violent terrorist threat also functions to render unclear whether the viewer may take what she sees at face value. Has the beautiful and seemingly vulnerable sleeping child Carrie grown into a paranoid, violent vigilante, who ignores the Brody family’s civil and moral right to privacy? Did the piano-playing Brody grow up to be a closet terrorist hiding behind the role of the returning war hero?

The series of maze-related shots proceeds to carry the mixture of fictionalized images of Carrie’s past and actual news coverage into the post-attack era of Homeland’s diegetic now, that is the timeframe in which the narrative takes place, with images of Brody’s rescue, his running to the White House, the time he spends in the bunker with the Vice President, and shots of Carrie’s watching his home using hidden cameras. To the accompaniment of a discordant Jazz score in the sound track, various bits of dialogue from the Pilot are interwoven, including the various announcements concerning terrorist attacks that Carrie witnesses while growing up. Amongst these is Carrie’s statement to her boss and mentor Saul Berenson that “it was right before my eyes” and that the September attacks could have been avoided if she had not “missed something” that day. She insists that “I’m not the one who got it wrong. I am the only one who got it right.” Signaling Carrie’s extraordinary vigilance as well as her paranoid sense that only she can deter another attack, these words highlight the equivalence that the credits make between Carrie’s certainty about her powers of acuity and the United States’ sense of its exceptionality and its extraordinary need to instate violent security measures after the attacks.

Yet this sequence of discordant images and sounds also suggests that Carrie and the series’ viewers, as witnesses to a visual history of her individual and America’s felt collective trauma, may simply be mistaken about security threats. The footage from Colin Powell’s address to the UN Security Council in 2003 in particular highlights this potential fallibility. Powell, it will be recalled, justified the US attack on and invasion of Iraq by arguing that Weapons of Mass Destruction were hidden in Iraq and that there was a direct link between Dictator Saddam Hussein and the September 2001 attacks. Yet Powell and the US were dead wrong: the evidence their case was based on was unsubstantiated or fraudulent. Subsequently, newspapers such as the New York Times made apologies for having colluded in Powell’s and the administration’s erroneous narrative, and the ensuing protracted, costly, and, for many, illegal war in Iraq has largely been regarded as a failure.20 Viewers may then, if unconsciously at this early point, question the validity of the premise of the first season that, as Carrie insists, the war hero Brody has become a sleeper terrorist, who was turned while he was in captivity. This lack of clarity as to the rightness of Carrie’s responses feeds into a sense of discomfort viewers may have about Carrie’s placing Brody and his entire family under 24/7 surveillance after his return and her uncannily watching their painful attempts to reconstitute their relationships with one another. One cannot be sure as to whether this family is not being victimized by Carrie’s aggressive and potentially paranoid sense of her own and the country’s vulnerability.

Viewers like the present author viewed the first television transmission of Homeland in Germany as the National Security Agency scandal was breaking in 2013 after Edward Snowden’s disclosures became widely known. Due to the ubiquity of dubbing all foreign language programming in Germany, series and movies generally appear at least a year after their date of their first transmission in the States. In 2013, it was revealed that the United States was regularly wire tapping Chancellor Merkel’s and other prominent politicians’ phones and placing Germany under general surveillance. Thus Carrie’s illegal surveillance of the Brody family found an unsavory political echo in evidence that the United States had placed its close ally Germany under permanent scrutiny as an apparent security threat.21 Brody’s abrupt realization that Carrie had been spying on him continuously for a long period of time in “The Weekend” and may not have been interested in him personally at all mirrored German citizens’ sense of betrayal at the invasive actions of their country’s close ally, the United States. The series has thus intersected with trans-Atlantic debates about global surveillance and the unilateral incursions of US American security measures into the civil rights of citizens outside its borders; this debate has also highlighted differences in protection, for instance, German citizens’ greater rights to data protection.

As is alluded to in the credit sequence, the footage garnered from Carrie’s surveillance operations gives the viewer privileged insight into the Brody household interior as well as the state of Marine Sergeant Nick Brody’s mind. The viewer participates in Carrie’s surveillance and in so doing becomes implicated in her actions. Brody appears to be suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, severe alienation from his wife, and bouts of uncontrolled aggression. He is also presented as a highly sympathetic character without any obvious signs of terrorist sentiment, although he is evidently hiding information about his captivity. In focalized flashbacks, we learn that he does know terrorist leader Abu Nazir, something he has denied in questioning, and that he has become a devout Muslim. Thus the viewer, like Carrie’s very few colleagues who know about her illegal surveillance operation, begins to question the validity of Carrie’s thesis that Brody is a terrorist in waiting, and indeed to question Carrie’s rationality itself. As the viewer learns, Carrie suffers from a severe bipolar condition that she has (improbably) kept secret from the CIA, and her manic behaviors increase exponentially throughout the first season.

The instability of perspective is underlined powerfully using visual means in a scene from “The Weekend.” It follows after the first time Carrie and Brody have sex without being drunk beforehand. The nature of their encounters has remained unclear, since it is not apparent whether or not Carrie has embarked on them solely to gather information about Brody’s possible terrorist activities. In scenes with Brody at her family’s cabin, it appears that Carrie’s feelings are genuine. Yet Carrie accidently reveals that she has been spying on Brody by mentioning his preferred brand of tea. Brody confronts her with her false play, and Carrie responds by openly voicing her suspicions about his being a sleeper terrorist. The audience’s probable shift of sympathy in this scene will be to Brody, who at this moment appears to explain everything that has remained doubtful about his behavior until this point in the narrative, including his knowing and liking his former captor Abu Nazir and his having (believed himself to have) been forced to kill his fellow POW and friend Corporal Thomas Walker. That Brody seems to prove all of Carrie’s suspicions wrong is underlined visually when basic aspects of continuity editing – that is that type of editing typically used in television and film to create a continuous sense of space – are violated.

Continuity editing stipulates that two people in dialogue be filmed in a sequence in which their spatial relationship is first established in a medium shot of both of them, and is then continued in a series of shots and reverse shots of their individual facial expressions. This sequence is always seen from one side of the imaginary axis that runs between them in what is called the 180° degree rule that helps viewers not to become disoriented and have the feeling of falling into space. Also called Hollywood editing, this seemingly invisible sequencing of shots constitutes a major part of conventional film and television visible aesthetics. Yet in this scene, the camera angle shifts suddenly from one side of the 180° axis to the other, and the usual shot/reverse shot sequence appears to be interrupted during the course of the characters’ confrontational exchange.

The audience first views Carrie and Brody’s argument from camera angles located on her left and his right side when she replies to his question about whether she has been watching him: “I don’t know what you mean” (Figure 5), and he then demands: “I mean, did you spy on me? You are a spy, right?” (Figure 6). Audience’s unconscious familiarity with the conventions of continuity editing will lead them to expect Carrie’s response to be shot from the same perspective as in Figure 5. Yet the camera now shows Carrie from the opposite side of the imaginary axis and the perspective from whence she was filmed before. Now seen from her right side, she replies: “Brody…” (Figure 7).

This abrupt cut with its attendant axis jump may not be intended to disorient the viewer but rather to underline a probable reversal of sympathies, as Brody appears to exonerate himself from all of Carrie’s suspicions about his actions. Viewers have been complicit with her mistrust, as they like Carrie placed Brody and his family under constant surveillance. Not only does it underscore the constant cat-and-mouse reversals that characterize Carrie and Brody’s relationship, but the break in continuity editing also suggests on a visual level that the viewer’s taking on any one perspective of events, either Carrie’s or Brody’s exclusively, may lead her to make grave mistakes in judgment.22

Figures 5, 6, 7: “The Weekend” (S01 E07), Homeland (2011 – present). Claire Danes and Damian Lewis, scene stills. 20th Television, 2012. Author’s screenshot.

Yet just as viewers have come, once again, to trust Brody and doubt Carrie’s suspicions, another reversal occurs. In a flashback, viewers discover that, after years of torture and imprisonment, Brody was made the English tutor to terrorist leader Abu Nazir’s young son Issa and that he came to care deeply for the boy. In the episode “Crossfire,” Brody’s perspective on how Issa was killed, along with eighty-two other children, is shown, when his madrassa was hit in a drone attack knowingly authorized by the Vice President William Walden and subsequently covered up by the CIA. The scenes of Brody bidding an affectionate and playful goodbye to Issa in English before the boy begins his school day, his hearing the bomb fall, and then searching for and finding Issa’s corpse amongst the ruins function to destabilize dominant ‘9/11’ representations. Here, a white American heterosexual father and military officer, who shares much in common with the normatively heroic figure in dominant ‘9/11’ texts, witnesses the loss of his quasi-adopted child to a drone attack. Through a process of visual transference, the sense of what it might feel like for the school of one’s own child to be bombed is evoked. Thereby, the usual invisibility and inaudibility of such targeted killings – to US Americans at least – is made affectively present through the sympathetic figure of Brody and this and subsequent scenes of his manly mourning.

Brody acts as a mediating figure in this scene, one who may allow for greater emotional empathy and identification on the US American viewer’s part. The quasi-sacral background music tells us, as do Brody’s tears and later mourning with the boy’s father Abu Nazir, what it might mean to experience such violent injustice that one could wish a politician’s death by any means. Thus the legitimacy of Brody’s desire to kill the Vice President and revenge Issa’s death becomes fathomable.

The audience’s viewing of this scene is rendered more complex because the sequence is reminiscent of news footage showing children and other Pakistani civilians who have been killed as supposed ‘collateral damage’ in drone attacks. As argued in conjunction with 24, fictional representations of violent counterterrorist measures in the post-‘9/11’ era provide platforms for Americans to discuss how justified these practices are. On a formal level, the drone sequence is also disturbingly familiar because it offers viewers strong visual reminders of typical ‘9/11’ iconography. This includes the camera’s concentration on the skeletal remains of the madrassa and the dust resulting out of its destruction. These shots are reminiscent of the synecdochic emphasis on the Twin Towers and their collapse after the attacks, with First Responders photographed, like Brody, moving amongst the dusty rubble and searching for survivors. ‘Our’ US American sense of wounding after the attacks is visually connected to the pain of those who in “Crossfire” search for dead children at the Ground Zero of the bombing of the madrassa.

Further, the drone sequence follows the plot elements of the out-of-nowhere narrative that ‘9/11’-timelines typically perpetuate, beginning on the morning of the attacks with the terrorists boarding planes in Boston, as though no historical events had preceded these acts whatsoever. Echoing Derrida’s early response to the September 2001 attacks, this scene suggests that US American policies have bred terrorist sentiment as in an autoimmune disease from within the body politic itself: if the attacks are understood in an extended metaphor as the body attacking itself, then the typical binaries of enemy versus war hero, foreigners versus citizens, and outside and inside are also rendered obsolete.23 The heroic POW returning soldier Brody now acts as the avenging terrorist in a kind of bloody Jacobean revenge tragedy that has been set in the present. Quoting Sean Higgens, “A more remarkable horror the show presents us with is a reflection of America in Brody himself, the American soldier turned terrorist. Here the show implicates the country in the creation of its own enemies, ultimately finding its monomania capable of corrupting even its own most violent protectors. It is Homeland’s most radical gesture to suggest that Americans, in the single-minded pursuit of their own safety, have made the ghosts they perceive and project a reality.”24

According to Timothy Melley, fictional representations such as 24 and Homeland offer forums in which the validity of American counterterrorist measures can be imagined and visualized, thereby counteracting the actual covertness with which these measures are legitimated and enacted and the human costs that they, and the imperialism they partake in, entail. Such “geopolitical melodramas” reiterate dominant ‘9/11’ representations by positing the nation as a blameless and exceptional victim.25 Further, as Melley states, the initial threat from an external terrorist dramatized in these melodramas is ultimately displaced by the even greater danger that comes from within, in the form of the corrupt American agent or politician. In Homeland’s first season, the immediate source of terrorist violence stems directly from the actions of Vice President Walden and CIA Counterterrorism Director David Estes. Thus, perspectives on security, violence, and terrorism other than US American ones are elided by the myopic focus on American characters and the peripherality of non-American ones.

As has been discussed above in relation to 24, these series are also cited in extratextual discussions about counterterrorist practices such as torture. Given this overlap between text and context, it is significant to recall that Homeland was one of President Barack Obama’s favorite series. Now called the “Drone President,” Obama, it will be recalled, authorized five times as many drone attacks as his predecessor, the pro-War on Terror Bush, and The New York Times reports that “drones have replaced Guantánamo as the recruiting tool of choice for militants.”26 As Obama reported to lead actor Damian Lewis, “While Michelle and the two girls go play tennis on Saturday afternoons, I go in the Oval Office, pretend I’m going to work, and then I switch on ‘Homeland.’”27 As Lewis described his response to this revelation in an interview: “The show has always been overtly political. It went straight to the heart of the drone argument. […] I can only imagine what he must be thinking when he watches a show like ours that explicitly deals with the collateral damage of drone strikes.”28 Politically sophisticated, the series thus provides comment on extra-textual political events and security policies and is also interfaced with discourse about the legitimacy of these practices.

Despite his having been prematurely awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2009, Obama became the Drone President. In an indirect comment on the series’ extra-textual context, Carrie Mathison is crowned the Drone Queen in the premiere episode of Homeland’s fourth season. There, the first season’s unabashed critique of the use of drones in “Crossfire” finds an echo in Carrie’s assumption of the part of Vice President Walden in season four, when she pooh-poohs the consequences of civilian deaths in targeted killings. As the CIA station chief in Kabul, Afghanistan she orders an air strike on a Pakistani farmhouse in what turns out to be a wedding in order to hit a high level terrorist target. A surviving guest has filmed the celebration on his phone, thus providing visual evidence of the CIA’s bombing of a wedding; this bombing has resulted in forty civilian deaths, and the video that documents it goes viral. Not only does the sequence of scenes from this episode reiterate imagery from “Crossfire” but it also functions to underline the dubious utilization of drones to fix the United States’ security problems. Drones provide supposedly ‘clean’ practices of warfare with no boots on the ground, yet the costs of the civilian deaths and injury they incur and the sense of fear produced by their constant buzzing overhead is anything but clean. The increased use of drones has also been part of a new era of visibility in which sympathies are garnered through visual documentation. The winners and losers of collective sympathies in violent conflicts are created as much through media representations and interventions as through combat, thus the private video of the bombing becomes a forceful indictment of American counterterrorist measures. Again, the series plays with its framing as fictional by constantly commenting on extra-textual political events and cultural trends as well as counterterrorist practices.

Visual Narrative Unreliability and the Questioning of Security Measures

The visual means described above, including the rough cut images of Carrie’s medial acculturation into a vigilant self-appointed guardian against terrorism, the interruption of continuity editing practices in “The Weekend,” and the sequence of scenes in “Crossfire,” all serve to create an instability of perspective on a formal level in Homeland. This instability suggests that the story that is related in the series cannot be taken at face value. Homeland strategically employs what I have called visual unreliability to urge the audience to interact with the plot more critically and consciously.

Let me explain narrative and visual unreliability more thoroughly. In the theory of Wayne Booth, Ansgar Nünning, and other scholars, narrator unreliability has traditionally been used to describe a phenomenon whereby the storyteller relates the story in a manner that cannot be trusted, despite the reader’s or listener’s quasi-automatic impulse to lend the story and storyteller credence unless there is clear evidence that one should not do so. According to most theories, the unreliability of the storytelling can occur because the storyteller is deluded, untrustworthy, or simply mistaken in her or his perceptions. If and when the story’s recipient recognizes signs of fallible or unreliable telling, she will work to understand it better by projecting a counter narrative in opposition to what has been literally told.29 She shall thereby assess that the narrator is unreliable and that she, as recipient, must detect an alternate and more accurate narrative than that which was related to her.

Yet, as I have argued elsewhere, rendering a story in an unstable or unreliable fashion does not have to document that the teller has a personal failing and is thus communicatively incompetent. Unreliable storytelling can also represent an “ideological stance,” whereby whoever creates the story builds in signs of unreliability in order to effect a critique of what the audience may be expecting to hear.30 This may include a critique of dominant ‘9/11’ narratives about the extraordinary suffering and victimization of Americans in the attacks, the entirely unprecedented and out-of-time nature of the attacks, and the need for retaliatory practices afterwards. Unreliability can then signal that there is a story behind the dominant one, and that other readings of US reactions to the events of 11 September 2001 are also legitimate. The employment of signs of fallibility can be used then to signal to the audience that they need to remain on their toes, to question what they see and hear, and not be too certain about the validity of their initial responses.31 With formal means, Homeland repeatedly expresses the unreliability of its narrative on a visual level as well as on a semantic, content-related one. Thus the series frequently suggests that Carrie is not only bipolar but also entirely out of control of her actions and that the country’s post-‘9/11’ policies of extralegal surveillance and drone use are also at best questionable. This becomes most clear in the first season’s drone scene, where the audience’s sympathies are clearly with the lovely dead boy and the two father figures who are joined in their grief for him.

The unreliability of Carrie’s and Brody’s characters and actions, and of the narrative itself, provides a critical and self-conscious reflection on several US American phenomena: reliance on drones as a weapon of choice and practice of surveillance, justifications for violent anti-terrorist measures, US allegations that reports on civilian deaths in drone strikes are Jihadist propaganda, surveillance measures, and the usefulness of torture as a technique for gathering information. This self-conscious representation of security measures may then indicate that the United States is no longer at a consensus about the need to do ‘whatever it takes’ – as in 24’s parlance – to combat terrorist threats.

Is Homeland really an Anti-24?

I do not in any way intend to create a hagiography around Homeland in this essay as an anti-24. The series’ politics are far too muddled and US-centric for that. Trenchant criticisms of Homeland include the series’ dilution of its nascent political critique due to its submission to the generic conventions of a twist-and-turn espionage thriller. Further, Homeland draws on stereotypes about women’s excessive emotionality through the presentation of Carrie’s romantic delusions about Brody and her bipolar condition, with its reiteration of the traditional collocation of femininity and hysteria.32 (Arguably, this changes in the series’ fourth season.) The series also trades in Orientalist clichés, for instance, with the first season’s Saudi Prince Farid Bin Abdud’s harem, with plentiful gratuitous scenes of the (normatively attractive) concubines’ nudity. Moreover, the series has been criticized for doing nothing at all to dispel anti-Arab racism.33 Although Carrie may appear more aware of the nuances of Islam than Jack Bauer, Homeland, as has been repeatedly argued “insists on an image of Muslim countries as homogeneous—loud, crowded, and aggressive—and of Muslims as overwhelmingly sadistic, barbaric, and morally bankrupt.”34 Ultimately, the real drama in Homeland concerns its US American counterterrorist protagonists and their miserable personal lives and conflicted relationships to their work. Perspectives other than theirs remain unseen.

Homeland’s stance in relation to terrorism may be closer to 24’s than its self-critical formal mechanics lead one initially to assume. Both series feature troubled, anti-authoritarian maverick protagonists, who are willing to go to extreme lengths, including repeatedly risking their own safety and reputations, to save the United States from terrorist attacks. Both texts dramatize the ubiquity of terrorist threats and suggest that the most extreme securitization means and savior-like outlaw figures are necessary to combat them.

In terms of its gender and ethnic politics, Homeland’s replacement of the white, heterosexual US American male anti-terrorist fighter with a white, female one is at best ambiguous in its reformist tendencies. Arguably, it represents a sleight-of-hand effort to update the traditional gender dynamics of the espionage thriller, which is not dissimilar from the casting of Sigourney Weaver as Ellen Ripley in Alien (1979). This move functioned successfully to revamp the by then somewhat tired figure of the patriarchal action hero by replacing him with a woman. Similarly, the casting of African American actors as anti-terrorist fighters in many dominant ‘9/11’ texts, such as The Kingdom (2007) with Jamie Foxx, did little to displace the continued racism that is endemic to US American culture. Nonetheless, re-casting the action hero as black did visually suggest that the marginalization of Muslims, Arabs, and Arab-looking individuals that followed in the post-attack era was on some level acceptable, since, seemingly, the former object of racial prejudice – the black man – was now the one in the position of power.35 In The Kingdom, Foxx’s character leads an action-packed, violent fight against terrorists in Saudi Arabia. Just as difficult woman Carrie’s strengths are offset by her romantic obsession with Brody and her phases of manic psychosis, so the ethnic-gender balance of dominant ‘9/11’ texts remains in place in Homeland. It is the feminized and youthful figure of Issa who stands at the affective center of the series’ first season. His violent victimization calls Brody to arms in his righteous quest to destroy the almost cardboard cutout villainous figure of Vice President Walden. This may be a retelling of the ‘White Man is needed to protect Brown Feminized Muslim’-narrative that is so painfully familiar from the majority of dominant ‘9/11’ texts.

This essay has argued that Homeland has to be considered as a post-‘9/11’ text due to its overt questioning of the validity of dominant ‘9/11’ texts and their complicity with post-attack narratives concerning the exceptionality of US American suffering and heroism and the need for retributive justice. My emphasis has been on how the series employs formal, visual means is intended to evoke doubt about the effectiveness of post-attack anti-terrorist measures. Visual unreliability is displayed in the series’ opening credits and in the violation of continuity editing rules in the episode “The Weekend,” and in the invocation of iconic ‘9/11’ images in the drone sequence from “Crossfire.” In the credits, the development of Carrie’s trustworthiness is placed under profound doubt through the visual means – the jarring cuts and the montage of highly misinformed reactions to the attacks, and Carrie’s hubristic and mistaken assumption that only she can keep a further attack from occurring. The credits comprise a collective televisual history of terrorist threats that simultaneously cast doubt on how this history should be interpreted: Colin Powell’s 2003 allegations concerning Weapons of Mass Destruction in Iraq proved to be wrong; the labyrinth imagery renders unclear whether Carrie is a predatory aggressor or a righteous defender of her country. Visual unreliability also underlies the subversion of continuity editing practices in the scene from “Weekend,” in which the viewer not only does not know which of the protagonists to trust but also is disrupted out of usual viewing patterns. The sequence involving Issa’s death in the drone attack creates a visual equivalence between US American suffering after the September 2001 attacks and the pain and loss felt by those who are subject to drone attacks by America. These formal measures function to destabilize dominant ‘9/11’ images and narratives and, I have argued, work to cast doubt on their legitimacy by suggesting that a counter narrative can also be detected.

Thus Homeland appears to be a far more enlightened version of its predecessors. Like other post-‘9/11’ series it employs strategies that critique dominant representations of the utility of torture and other violent security measures that characterized the Bush era. Yet, as the last part of this essay has pointed out, the series’ overtly critical stance may ultimately represent a more considered form of complicity with the Obama administration’s enhanced use of drone strikes and other surveillance technologies than that of ‘9/11’-texts of the dominant type. Homeland is more ideologically effective than its predecessors precisely because of its veneer of self-reflexivity. In this vein, James Castonquay argues that the series’ seeming “progressive polysemy” has been “effectively contained, controlled, and rearticulated through a complex narrative structure that may continue to do its ideological work on behalf of the Obama administration’s aggressive counterterrorism policies.”36 Terrorist threats remain constant and threatening, Homeland tells and shows us; only extraordinary individuals using extreme illegal means can combat them. Further, the series’ focus on white American figures as sources of threat and of protection reiterates tropes of US exceptionality and isolationism. Homeland is a post-‘9/11’ text whose politics may not be post enough.

- The reader will note that I refer to ‘9/11’ using single quotation marks to signal that this nomenclature is in itself part of the dominant representations of the events surrounding 11 September 2001. The expression serves to memorialize events in a particular manner by suggesting that the attacks had no history and by eliding other historical 9/11s, including the US-backed overthrow of democratically elected Chilean President Salvador Allende in 1973. ↩

- See Georgianna Banita, Plotting Justice: Narrative Ethics and Literary Culture after 9/11 (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 2012); Greta Olson, “Reading 9/11 Texts through the Lens of Critical Media Studies,” New Theories, Models and Methods in Literary and Cultural Studies: Theory into Practice, eds. Greta Olson and Ansgar Nünning (Trier: Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier, 2013), 161-185; and Elizabeth Kovach, Novel Ontologies after 9/11: The Politics of Being in Contemporary Theory and U.S.-American Narrative Fiction (Trier: Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier, 2016). ↩

- See Quality TV: Contemporary American Television and Beyond, eds. Janet McCabe and Kim Akass (London and New York: Tauris 2007), Jason Mittel, Complex TV: The Poetics of Contemporary Television (Combined Academic Publ., 2015) and on class assumptions in the valuation of “quality,” see Dan Hassler-Forest, “Game of Thrones: Quality Television and the Cultural Logic of Gentrification,” TV/Series #6 (December 2014): 160-177 and Diana Negra and Jorie Lagewey, “Analyzing Homeland: Introduction,” Cinema Journal 54.4 (Summer 2015): 126-131. For associations of “quality” with masculine drama and melodrama and a masculinist aesthetics, see in particular Geraldine Harris: “A Return to Form? Postmasculinist Television Drama and Tragic Heroes in the Wake of The Sopranos,” New Review of Film and Television Studies 10.4: 443-463, and Emily Nussbaum, “Difficult women: How Sex and the City Lost its Good Name,” The New Yorker (29 July, 2013), online: http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2013/07/29/difficult-women. ↩

- See Amanda Lotz, Beyond Prime Time: Television Programming in the Post-Network Era (New York and Oxon: Routledge, 2009). ↩

- See Greta Olson, “Reading 9/11 Texts through the Lens of Critical Media Studies.” ↩

- The gendering of a White, female country in need of protection coheres with a long history of racist and jingoistic representations. On gender and ‘9/11,’ see Birte Christ, “Männer,” 9/11: Kein Tag, der die Welt veränderte, eds. Michael Butter, Birte Christ, and Patrick Keller (Paderborn: Schöningh, 2011), 91-205. See also Susan Faludi, The Terror Dream: Fear and Fantasy in Post 9/11 America (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2007), and Greta Olson, “Reading 9/11 Texts through the Lens of Critical Media Studies.” ↩

- George W. Bush, “Today … our very freedom came under attack,” The Boston Globe (September 12, 2001), online: http://www.boston.com/news/packages/underattack/globe_stories/0912/_Today_our_very_freedom_came_under_attack_+.shtml. ↩

- Steven Salaita, “Beyond Orientalism and Islamophobia: 9/11, Anti-Arab Racism, and the Mythos of National Pride,” The New Centennial Review 6.2 (2007): 245-266; Moustafa Bayoumi, “The Race Is On: On Muslims and Arabs in the American Imagination,” Middle East Research and Information Project (March 2010), online: http://www.merip.org/mero/interventions/race; and Peter Morey, “Terrorvision: Race, Nation and Muslimness in Fox’s 24,” Interventions: International Journal of Postcolonial Studies 12.2 (2010): 251-264. ↩

- Emily Nussbaum, “Homeland: The Antidote for ‘24’,” The New Yorker (November 29, 2011), online: http://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/homeland-the-antidote-for-24. ↩

- Jonathan Alter, “Time to Think About Torture,” Newsweek (September 4, 2001), online: http://www.newsweek.com/time-think-about-torture-149445. ↩

- Jane Mayer, “Whatever It Takes: The Politics of the Man Behind ‘24’,” The New Yorker (19 February, 2007), online: http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2007/02/19/whatever-it-takes. ↩

- Peter Lattmann, “Justice Scalia Hearts Jack Bauer,” Law Blog, Wall Street Journal (June 20, 2007), online: http://blogs.wsj.com/law/2007/06/20/justice-scalia-hearts-jack-bauer/. ↩

- See Alan Dershowitz, “Tortured Reasoning,” Torture: A Collection, ed. Sanford Levinson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 257-280. ↩

- Douglas L. Howard, “You’re Going to Tell Me Everything You Know: Torture and Morality in Fox’s 24,” Reading 24: TV Against the Clock, ed. Steven Peacock (London and New York: Tauris, 2007), 140-141. ↩

- Stephen Stockwell, “Messages from the Apocalypse: Security Issues in American TV Series,” Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies 25. 2 (2011), 188-199, 194. ↩

- Timothy Melley argues that due to the secrecy of security practices in the United States fictional representations present platforms for resolving anxieties about them: Timothy Melley, “The Geopolitical Melodrama,” The Covert Sphere (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2012), 199-222. ↩

- See Martin Hipsky, “Post-Cold War Paranoia in The Corrections and The Sopranos,” Postmodern Culture 16.2 (2006): 1-45. ↩

- Eric Gould, “Main Titles Up Close: Showtime’s ‘Homeland,’” TV Worth Watching (December 14, 2012), online: http://www.tvworthwatching.com/post/Main-Titles-Up-Close-Homeland.aspx#comments. ↩

- In referring to the female protagonist by her first name and the male protagonist with his second name, I recognize that I am reiterating a sexist practice of arguably infantilizing women by assuming the familiar address with them. This is, however, also the pattern of address within the series and in most commentary about it. ↩

- Daniel Okrent, “The Public Editor: Weapons of Mass Destructions? Or Mass Distractions?” The New York Times (May 30, 2004), online: http://www.nytimes.com/2004/05/30/weekinreview/the-public-editor-weapons-of-mass-destruction-or-mass-distraction.html?pagewanted=all&src=pm. ↩

- See Vinzenz Hediger, „Einübung in paranoides Denken: ‚The Wire‘, ‚Homeland‘ und die filmische Ästhetik des Überwachungsstaats,“ Forschung & Lehre 8 (2013): 617-619. ↩

- This reading of the image sequence was suggested to me by Lisa Charlotte Friedrich’s “My Wish for the Right Perspective: An Essay on the Showtime Series Homeland,” (term paper, University of Giessen, 2014). ↩

- Giovanna Borradori, “Autoimmunity: Real and Symbolic Suicides. A Dialogue with Jacques Derrida,” Philosophy in a Time of Terror: Dialogues with Jürgen Habermas and Jacques Derrida (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 85-136. ↩

- Sean Higgins, “The Haunting of ‘Homeland’: On Showtime’s ‘Homeland,’ an American Ghost Story,” Los Angeles Review of Books (October 9, 2012), online: https://lareviewofbooks.org/essay/the-haunting-of-homeland. ↩

- Timothy Melley, “The Geopolitical Melodrama,” The Covert Sphere (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2012), 201. ↩

- Jo Becker and Shane Scott, “Secret ‘Kill List’ Proves a Test of Obama’s Principle and Will,” The New York Times (May 29, 2012), online: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/29/world/obamas-leadership-in-war-on-al-qaeda.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0. ↩

- Leslie Savan, “Homeland’s Anti-Drone Message Hits Obama at Home,” The Nation (December 10, 2012), online: http://www.thenation.com/article/homelands-anti-drone-message-hits-obama-home/. ↩

- Scott Meslow, “How ‘Homeland’ Finds Humanity in Terrorism,” The Atlantic (September 28, 2012), online: http://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2012/09/how-homeland-finds-humanity-in-terrorism/262975/. ↩

- For overviews, see Wayne Booth, The Rhetoric of Fiction (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1961); Greta Olson, “Reconsidering Unreliability: Fallible and Untrustworthy Narrators,” Narrative 11.1 (January 2003): 93-109; Ansgar Nünning, “Reconceptualizing Unreliable Narration: Synthesizing Cognitive and Rhetorical Approaches,” A Companion to Narrative Theory, eds. J. Phelan & P. J. Rabinowitz (Oxford: Blackwell, 2005), 89-107; and Dan Shen, “Unreliability,” The Living Handbook of Narratology (June 27, 2011), online: http://wikis.sub.uni-hamburg.de/lhn/index.php/Unreliability amongst others. The term unreliable narrator, then, to describe the imagined person behind the story, has been extended to describe the narrative or told story itself, as in Gregory Currie, “Unreliability Refigured: Narrative in Literature and Film,” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 53.1 (1995): 19-29. ↩

- Susan Sniader Lanser, The Narrative Act: Point of View in Prose Fiction (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981), 216-217. ↩

- I outline this revision of unreliability in Olson, “Questioning the Ideology of Reliability in Mohsin Hamid’s The Reluctant Fundamentalist: Towards a Critical, Culturalist Narratology,” Narratology and Ideology: Encounters between Narrative Theory and Postcolonial Criticism, eds. Divya Dwivedi, Henrik Skov Nielsen, and Richard Walsh (Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press, forthcoming). ↩

- For an alternative reading of Carrie’s gender in relation to security see Alex Bevan, “The National Body, Women, and Mental Health in Homeland,” Cinema Journal 54.4 (Summer 2015): 145-151. ↩

- See Joseph Massad, “‘Homeland,’ Obama’s Show,” Al Jazeera (October 25, 2012), online: http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2012/10/2012102591525809725.html. ↩

- Rozina Ali, “How ‘Homeland’ Helps Justify the War on Terror,” The New Yorker (December 20, 2015), online: http://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/how-homeland-helps-justify-the-war-on-terror. ↩

- See Peter Morey, “Terrorvision: Race, Nation and Muslimness in Fox’s 24” and Moustafa Bayoumi, “The Race Is On: Muslims and Arabs in the American Imagination.” ↩

- James Castonguay, “Fictions of Terror: Complexity, Complicity and Insecurity in Homeland,” Cinema Journal 54.4 (Summer 2015): 139-145, 145. ↩