by Benjamin Haber and Daniel J Sander

The original context of the above tweet, which preceded Twitter’s introduction of threads, was part of a longer ironic statement in support of the legalization of gay marriage in the state of New York.1 Baldwin suggested that if one really opposed such a move, especially on religious grounds, then they should perform an incantation, and “all the gay people will disappear.” In late 2020 and early 2021, Baldwin’s tweet began recirculating out of context, divorced from the original discussion around gay marriage. Instead, queers, in replies and quote tweets, affirmed the at times self-deprecating idea that “gay people,” primarily signifying cis white homosexuals, had overstayed their welcome, becoming cringeworthy, and really ought to disappear. In highlighting the playful stretching of Baldwin’s tweet back and forward in time, we look to foreground a shift in queer representation as marked for death to one bored to death.

For Douglas Crimp, the disappearance of gay representation during the advent of the HIV/AIDS pandemic was paradoxically achieved through new forms of overdetermined personal portraiture, eliding the murderous government negligence of the state with the personal, private, and family-forward tragic victim. In his iconic piece “Portraits of People with AIDS,” Crimp highlights the propensity of the news media and mainstream artists of the time to frame the AIDS victim as either monster or mirror, as otherness incarnate or as otherness erased. For Crimp, this representational violence demands more complex and political representations, an active media practice that understands that, “AIDS does not exist apart from the practices that conceptualize it, represent it, and respond to it.”2 With this focus on the significance of decentralized activist practice to marginalized people, Crimp anticipates the social media archive that we focus on in this piece: tweets, memes, TikToks, and other digital ephemera that now largely drive mainstream media representations:

But we must also recognize that every image of a PWA is a representation, and formulate our activist demands not in relation to the “truth” of the image, but in relation to the conditions of its construction and to its social effects.3

In 2020, many queers were wishing a specific breed of gay cringe would disappear: COVID Corey, Puerto Vallarta Gays, Vaccinated Tops, and other well-off, mostly white avatars of striking privilege during crisis. In “Portraits…”, Crimp suggests that one of the central motivating affects of AIDS portraiture is a thinly veiled disgust and terror directed toward the bodies of queers and IV drug users, bodies framed as, at best, having lost their agency through their pathological desires. If Crimp’s writing highlights the centrality of the wasting queer (and queered) body in framing the AIDS pandemic and fantasies of quarantine, in our current pandemic, representations of the contemporary clueless, chiseled gay has inspired something like a queer homophobia, a collective visceral embarrassment at the persistence of gay sociality in a world ground to a halt. And while Crimp suggests a recuperation of representation through a complex, fleshy, and loving reclamation of the slut and the junkie (an ongoing project of continued importance), our work here looks to the ends of representation.

Contemporaneous with Crimp’s representational analysis, and working through the same archive of straight animus and disgust of the queered AIDS body, Leo Bersani’s version of the anti-relational thesis moves to embrace the “suicidal ecstacy” of the subject undone by sex.4 According to Bersani, gay male penetrative sex is significant primarily because it shatters the self and hence the opportunity for intersubjectivity, i.e. “the inestimable value of sex as — at least in certain of its ineradicable aspects — anticommunal, antiegalitarian, antinurturing, antiloving.”5 Gay male sex here expresses the “sensations or affective processes somehow ‘beyond’ those connected with psychic organization” and is associated with non-reproduction and a removal from communication and relationality.6

Online, however, intense bodily sensation does not dissolve individuality into the potentiality of anonymity and impersonality but is circulated through a sort of memeified publicity: “Social media had turned the individual into a media object. We were no longer so much ourselves, as the effervescent content that trailed us through our lives.”7 As content, gay becomes just another quality among an infinite array of qualities that can be categorized and quantified.

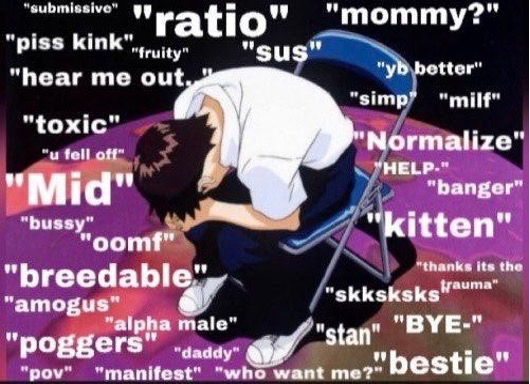

Nowadays, the potential of bottoming is not be found in a negation of self but in an affirmation of being, conferring a certain status and esteem, a badge of pride in objectification: not the rectum is a grave, but I’m just a hole, sir, where the “just” belies a competition among simps, oomfies, reply guys, and pick me gays to be the most adept, the most qualified, the most submissive and breedable, not necessarily in terms of physical prowess, but in terms of garnering the most attention, the most laughs, the most likes.

While his provocation is ultimately to think “the possibility of a non-white erotics of selfshattering”, Bobby Benedicto has written about how the conversion of homosexuality into a “form of life” has eased the death drive of the unmarked (read: white) homosexual.8 Take the submissive and breedable mask, above, sold as a fundraiser for John Drake, a young, white, TikTok twink and a fringe candidate for California’s recent gubernatorial recall election.9 A satire of gay danger that folds bareback sex back into the responsible, liberal, mask-wearing subject (albeit with a cheeky wink to an anachronistic death drive), this queer object reflects the emergence of a stylized form of death-inflected identity play, a play that maintains a historic attachment to danger while risking little. Or as Benedicto puts it, “whatever threat homosexuality poses to the sanctity of life does not come from the fulfillment of the wish to collapse self-love and object-love but from the willingness to pursue this wish despite its impossibility and the proximity to death it demands.”10

We have suggested that a theorized desire, often coded as white, to self-annihilate with bareback sex has, abetted by digital technology, flipped into an identity in and of itself. Doubling down on the perceived political correctness of visibility and representation, the impulse to identify queerly is increasingly becoming untethered from sex acts, if not, at times, reverting into sex negativity (an inversion of the negativity of sex). Social media bios are rife with extended, hyphenated lists of not only sex/gender/sexuality markers, but also mental health signifiers and political and religious affiliations. While it is now less likely for sodomy to be linked to physical or psychic death, the surfeit of identity nevertheless risks extinguishing the subject.

This extinguishing, or more nearly, exhaustion of the subject is vividly reflected in the persistence of the meme “the mortifying ordeal of being known” and its child, “don’t perceive me”. R.E. Hawley sees the continuing popularity of these memes as evidence of a recently accelerated “creeping claustrophobia” born of social media’s insatiable demand for representation.11 For Hawley, we might productively respond to this exhaustion with a tactical form of online dissociation, with hopes of a more playful internet “free from compulsory body awareness.”12

Captioned with the longform version of the meme, “the rewards of being loved versus the mortifying ordeal of being known”, the above TikTok shows a cat, Momo, choosing their pronouns, sexuality, religion, and political orientation through a game where the first piece of crumpled up paper that Momo shows an interest in reveals their choice of subject position. (Momo is apparently a they/them, pansexual, Catholic, Maoist.) While subjectivity is playfully framed as a prerequisite for being loved, Momo’s love might be better understood as being grounded in a foundational resistance to ever really being known. Identity here is literally a game of chance, put on like a flashy accessory that serves to heighten our attention to the inaccessibility underneath. Indeed, TikTok frequently features pets that delight precisely because of their inability to ever really be understood, and thus our perception is given permission to stay in the affective.

Consider, too, Noodles, another celebrity pet to rise from TikTok, whose countenance and posture each morning is read through the productive binary of “bones” vs. “no bones,” i.e., Noodles’ reaction to being roused is either to stay sitting or to slink down into a puddle. Noodles’ generative yet inscrutable posturing is treated as a quasi-astrological signal of daily capacity, with a “no bones day” giving permission to crumple back into bed, away from the fatiguing obligations of everyday perception, the labor of which may be especially acute for those whose self-presentations resist easy categorization.

In contrast, we might look to the main character meme, which posits the social media user as the star of various performances of the self, where perception is both goal and obligation. Being the main character can ironize a culture of narcissism, provide the comfort of recognition, and/or make a bid for social and financial capital. This insistence on (se)eking out a granular self through social media reflects our attempts at alleviating loneliness through being seen. However, it also reveals the trap of identity, as a hero’s quest of becoming known reaches the inevitable letdown of being known (which is where the movie ends because to endure the transition from the quest of self-discovery to the mundane stagnation of ongoing identification would be too boring).

We have explored the ways in which Alec Baldwin’s words “all the gay people will disappear” have anachronistic resonances with Douglas Crimp’s activist-inflected readings and deployments of HIV/AIDS media and with Leo Bersani’s psychic disorganization wrought by sex. Today, however, evidences the desire for a new kind of disappearance, one that is not about being perceived as gay or about being perceived as anything else at all for that matter. Rather than becoming the main character, queen of representation, we might aspire to the non-player character, or NPC, which appears just as frequently on TikTok. In video games, NPCs are characters whose limited behaviors are automated, designed to be objects of partial attention, like extras. Freed from the main gaze of the player, NPCs might get quickly knocked off screen, or forgotten, but are essential for creating a social ambiance.

Coco Klockner suggests, however, that NPCs and main characters might not be such a contrast after all:

Counterpoised with main character energy, NPCs point to a broader tension regarding interiority in general. If we are constantly performing the self to the ubiquitous and persistent audiences that social media platforms provide, then interiority is no longer central to selfhood and no longer assumed in the same way. Instead, our performances establish ourselves for others, and how those performances are received conveys a sense of selfhood back to us. That brings main character energy perilously close to NPC-hood. To be without visible main character energy is to be indistinguishable from the walking automaton.13

In other words, main characters suggest an interiority, a there there to the self, that ironically can only be “proven” through ongoing externalization. The performance of main character energy on social media then is sort of like the Calvinist performance of predestination: a supposedly immutable quality must constantly be performed to prove to others this performance is natural, correct, and a seamless reflection of true self. Still, for Klockner, an embrace of the “ontology of the NPC” might provide us with a kind of sublime leisure, “a position from which interiorities are not regularly excavated and from which self-referential performances are not demanded.”14

On TikTok, however, even NPCs must have a story, a comments section filled with speculation, building a history, a motivation, a selfhood. With so many NPCs in our insistently immersive experiences, some are bound to glitch, making us wonder, who really is the subject here?

In the end, we might need not only the tactical dissociation of digital strategies that seek to help us avoid the exhaustion of online perception, but also the more everyday forms of mundane dissociation that now pockmark many of our lives. Maybe gays really do need to disappear — at least from this cacophonous world of compulsory identification — and to luxuriate in the silence of non-association to reemerge into new forms of association, above, below, and in between representation.

***

Benjamin Haber is a Visiting Assistant Professor of Sociology at Wesleyan University, and has taught at Hunter College, New York University and Columbia University. Benjamin’s work has been published in a variety of edited collections, magazines and journals, including Media, Culture & Society, WSQ, Women & Performance, boundary2, Real Life, and the volumes Digital Sociologies and Nonrepresentational Methodologies: Re-envisioning Research.

Daniel J Sander is an independent academic and curator with a PhD in Performance Studies from New York University. He has taught at New York University and Yale University and been a guest lecturer, critic, and/or reviewer at the Rhode Island School of Design, the International Center of Photography, Hunter College, University of Mississippi, New York University, Pratt Institute, Maple Terrace, Parsons School of Design, and the Wassaic Project. He was a 20192020 Curator-Mentor for CUE Art Foundation’s Open Call.

- Threads allowed for tweets to be structurally linked together ↩

- Douglas Crimp, “AIDS: Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism,” October 43 (1987): 3 ↩

- Douglas Crimp, “Portraits of People with AIDS,” in Cultural Studies, ed. Lawrence Grossberg, Cary Nelson, and Paula Treichler (New York: Routledge, 1991), 126 ↩

- Leo Bersani, “Is the Rectum a Grave?” October 43 (1987): 212 ↩

- Bersani, “Is the Rectum a Grave?,” 215 ↩

- Bersani, “Is the Rectum a Grave?,” 217 ↩

- Sean Monahan, “It’s Always Halloween Online,” Spike 69 (2021): 62 ↩

- Bobby Benedicto, “Agents and Objects of Death: Gay Murder, Boyfriend Twins, and Queer of Color Negativity,” GLQ 25, no. 2 (2019): 291 ↩

- In which the current governor, Gavin Newsom, won by almost the exact same margin as his 2018 election ↩

- Benedicto, 281 ↩

- R.E. Hawley, “I’m Not There”, Real Life (2021): https://reallifemag.com/im-not-there/ ↩

- Hawley, “I’m Not There” ↩

- Coco Klockner, “Main Character Energy,” Real Life (2021): https://reallifemag.com/main-characterenergy/ ↩

- Klockner, “Main Character Energy” ↩