Douglas Crimp is an art critic and the Fanny Knapp Professor of Art History at the University of Rochester. He is the author and editor of numerous books, including Melancholia and Moralism: Essays on AIDS and Queer Politics, “Our Kind of Movie”: The Films of Andy Warhol, On the Museum’s Ruins, and AIDS: Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism. Crimp was the curator of the landmark Pictures exhibition at Artists Space in 1977. He is widely known for his work with the “Pictures Generation” and his influence is extensively recognized in a varied range of disciplines such as art history and criticism, LGBTQ studies, political activism, and dance studies. Part autobiography and part cultural history, Crimp’s latest book Before Pictures, offers a moving and intimate account of his experience as a young queer man and aspiring art critic in the late ’60s and ’70s in New York.

Douglas Crimp remains a formative figure in the Visual and Cultural Studies Graduate Program at the University of Rochester, at which InVisible Culture is based. The following interview with the Managing Editor of InVisible Culture took place in the Spring of 2017.

Hend Alawadhi: Congratulations on the release of your memoir Before Pictures. We’ve been following your book tour from Rochester with a lot of excitement. Can you talk a little about the genesis of this project? When did you start working on it and how does it relate to your earlier work, Melancholia and Moralism, for example?

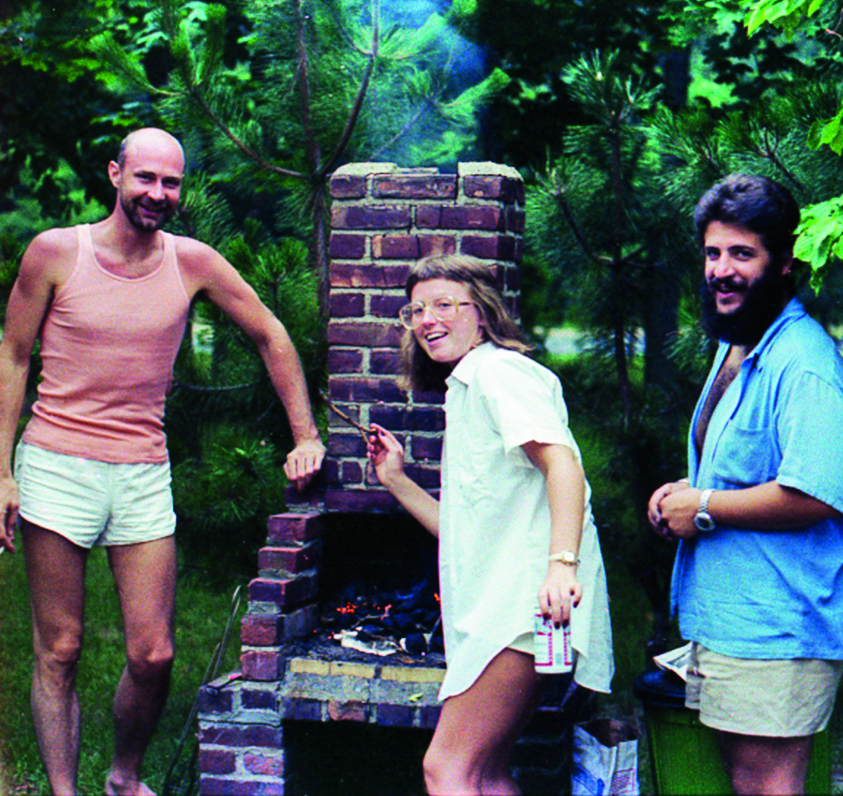

Douglas Crimp: In fact, Before Pictures relates directly to my writing on AIDS collected in Melancholia and Moralism (2002). My AIDS work resulted from my involvement with the AIDS activist group ACT UP. During those years—1987-1991—I developed many new friendships with people twenty years or so younger than I. They hadn’t experienced the efflorescence of gay sexual culture in New York during the 1970s that I had, and we often talked about it. We all wanted to counter the revisionist—and to our minds entirely false—narrative that was being promoted by gay conservatives: that the period of gay liberation represented gay men’s immaturity and led inevitably to the epidemic, which taught us to grow up and become responsible citizens. Many of my fellow activists urged me to write about gay life in the 1970s as I had experienced it in order to counter that narrative. My intellectual commitments had by then changed from art criticism to cultural studies and queer theory, both of which were politically engaged endeavors and also entailed what I would call “a turn toward the subject.” That is, not only was subjectivity one of our subjects, but also we took our own subjectivities as something both to be interrogated and to be “at stake” in our work. One result was that an autobiographical dimension entered my writing. This happened first and foremost in my writing about AIDS, much of which is highly personal. But it also governed my work that followed, on Andy Warhol’s films, which I began in the late 1990s. I had forecast a project on 1960s queer culture in my essay “Getting the Warhol We Deserve” (published in InVisible Culture, Issue 1), which would eventually become my book “Our Kind of Movie”: The Films of Andy Warhol (2012). I saw the book as an archeology of the queer world I discovered at the art bar Max’s Kanas City, in whose back room the Warhol crowd hung out in the late 1960s. I think of that as the place where I learned how to be queer in New York City, after having learned a different way to be queer in my student days in New Orleans, where I frequented sailors’ bars on Decatur Street. There are some memoir-like moments in “Our Kind of Movie”, including an account of having seen The Chelsea Girls in New Orleans during its national release, and more importantly, the story of giving my mother’s dinner dress, designed by Hollywood costume designer Adrian, to Warhol superstar Holly Woodlawn when she briefly lived with me. By the time I wrote that as an addendum to the chapter about Screen Test no. 2, I had already begun writing Before Pictures; I essentially stole that story from the memoir to put in the book on Warhol.

In 2005, the Guggenheim Museum invited me to give a lecture in conjunction with their exhibition The Eye of the Storm: Works in situ by Daniel Buren, knowing that I was working at the museum in 1971 when Buren’s Painting-Sculpture was famously—or rather infamously—removed from the Sixth Guggenheim International Exhibition. I was hesitant to become the truth-teller, the person who knew and could tell the inside story of why the piece was removed. So I complicated the story of what I had always referred to as my first job in New York—working at the Guggenheim—with the story of my actual first job in New York, helping Charles James organize his papers to write a memoir (which sadly he never did, even though he had three separate commissions to write his autobiography during his lifetime). Those two stories’ seemingly incommensurable subjects—conceptual art and haute couture—and the queer way I wove them together provided me with a model for how to write Before Pictures, and I was on my way.

Douglas Crimp in his Guggenheim office, c. 1971

Alawadhi: How has the LGBT liberation movement dovetailed with your work and time in Rochester? I know that you initiated the Craig Owens lecture and that meant a lot to you, as well as the fact that many of your classes have been structured around your time in New York and your work as an activist.

Crimp: When I came to Rochester in 1992, I was still writing exclusively about AIDS. I was hired to fill the position left vacant by Craig when he died of AIDS in 1990. There had been talk of establishing an annual lecture in his honor, and in fact Michael Ann Holly organized the first of the Owens events in 1992, with lectures by Mieke Bal and me. But that turned out to be a one-off thing until I was hired full-time in 1996, at which point I asked for and received funding from the College for an annual memorial lecture. We’ve had one every year since 1996. In the 1990s, when I taught courses on AIDS, queer theory, and cultural studies, I certainly thought of pedagogy as a form of political engagement. Since then, in courses on Andy Warhol, Yvonne Rainer, and New York in the 1970s, queer theory and feminism have continued to inform my teaching. Inevitably my political commitments inflect what I do, and probably we’re all going to have to step that up in the present climate. I just heard from my friend Karen Redrobe, who briefly taught at Rochester but is now at Penn, that she and artist Sharon Hayes are planning to team-teach a course on art and protest at Penn. Sounds like a good idea.

Alawadhi: That sounds like a great idea. During your book tour you presented and discussed your memoir in a number of different geographical contexts. How has the book resonated in different locations during the book tour?

Crimp: I chose what sections of the book to read depending on the place and on my interlocutor for the conversations that followed the readings. If there was some small story that resonated particularly with a city I was reading in, I would choose that. For example, at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, I read the story about my first trip to L.A. in 1977, when Bette Davis was on my plane on my way out and then I happened to be seated next to Arnold Schwarzenegger on the way back. But I also read from the introduction about my time at New Orleans, because my interlocutor at the Hammer was Jacquelyn McCroskey, a professor of child welfare in the USC School of Social Work, who was a fellow student and friend at Tulane and my oldest friend in L.A. But I think it hasn’t really mattered what parts I read or what got covered in the conversations afterward; people have been very responsive, and it’s been very gratifying. I was in Marfa, TX for a reading when Trump was elected. Right after that, I had events in Houston and Austin, followed soon my one in Philadelphia, and my audiences expressed their gratitude for getting a break from thinking about the catastrophe that had just occurred.

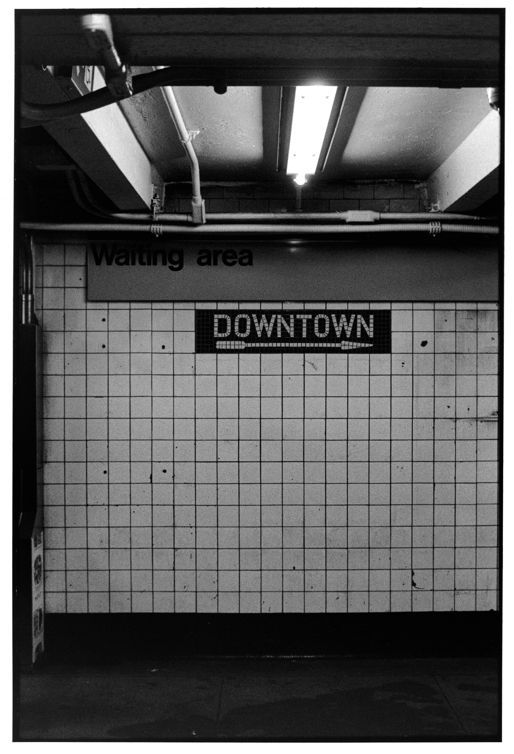

Zoe Loenard, chapter divider photograph for “Before Pictures”, detail of “Downtown (for Douglas),” 2016

Alawadhi: I saw the letter in your show at the Buchholz Galerie from Julie Fallowfield regarding the Moroccan cookbook, explaining how she had contacted many publishers to consider it – which sadly didn’t work out. We usually have very formulaic ideas about writing, especially in academia. The draft is written, edited, and is ultimately published. What becomes of projects that do not follow this trajectory, such as the cookbook and your writing about disco? How do unfinished projects live? It is quite hard to conceive that Douglas Crimp has a dog-eared folder marked “projects.”

Crimp: Well, you must understand that my writing during the period covered in Before Pictures did not develop in an academic setting, at least not until I went to graduate school in 1976. I wanted to be a critic, a writer, and my ideas about what that meant came from reading art magazines in college and eventually writing articles and reviews for Art News and Art International. But writing didn’t mean only art criticism for me. You might remember that in the chapter “Art News Parties,” I write about boasting to Marilyn Goldin at John Ashbery’s party that I’m planning to write a book about transvestites. Obviously that came to nothing, but it was a genuine, if half-baked, ambition. The Moroccan cookbook was strictly my boyfriend Christian and my scheme to make money, but still, I had to take seriously the prose I crafted for the chapter introductions. The project wouldn’t stand a chance of being published if the writing didn’t pass muster. I kept the project in a folder because I continue to use the test recipes that we wrote. And then there was the project on disco, which went nowhere, but I was attached enough to it to keep in in my filing cabinet for forty years. I’m glad I did, because it forms the basis of the chapter on disco in Before Pictures. I pre-published that chapter both in a special issue on disco in Criticism: A Quarterly for Literature and the Arts and as one of the chapbooks done in conjunction with the 2015 Greater New York exhibition at MoMA PS1, so it’s already had quite a life and gotten a lot of attention. Harpers Magazine even published a short excerpt from it around the time the book came out.

Alawadhi: The design of book is really remarkable, the typeface, the layout and the reproduction of the images are all very beautiful. Were you involved in the design at all? I’m particularly interested in the relation between Zoe Leonard’s images and the subway maps that are somewhat of a visual preface to the book. Was inhabiting and navigating New York inextricable from the subways?

Zoe Loenard, cover photograph for “Before Pictures”, detail of “Downtown (for Douglas),” 2016

Crimp: I had always wanted this book to be fully illustrated and designed by someone intimately involved with the project, and I was very lucky that that came to pass. I had met Joseph Logan, who designed Before Pictures, when, as Artforum’s designer, he laid out my article on Merce Cunningham’s Beacon Events. Later, Zoe Leonard sang Joseph’s praises to me after he designed her Dia book, You see I am here after all. I knew he was a gifted designer and a total sweetheart of a person; Zoe told me how thoroughly collaborative he was to work with. That turned out to be 100% true. It was Joseph who suggested I talk to Karen Kelly and Barbara Schroeter when they were starting Dancing Foxes Press. I knew them slightly from working with them on the Dia Foundation’s Agnes Martin Book. That was the team (which also included Joseph’s assistant Rachel Hudson) that produced the book I really wanted, and we all worked together from start to finish. I was involved with virtually every decision, including choosing the typeface and size. But honestly I didn’t have to be; they are all such professionals that you can trust their every decision. Karen and Barbara often print their books at die Keuere in Bruges, because the printer lets them go on press to color correct, something Barbara is especially good at.

Zoe came to the project later, when we decided to divide up the chapters according to the five places I’ve lived in in New York. We wanted pictures of them, and I thought of Zoe, who luckily agreed. She and I did a tour of my former and current addresses one summer day, taking subways to get from Spanish Harlem to Chelsea to the Village, and so forth. By the end of the day, Zoe had begun to think about the nearby subway stops in addition to the building facades. That turned out to be sheer genius on her part. I had all along wanted to include Massimo Vignelli’s 1972 subway map design. It only lasted in the subways for a short time, because people found it difficult to read, but I love it. Joseph decided right away to use it for the endpapers. When Zoe presented us with the contact sheets of her beautiful photographs of the five buildings and nearby subway stops, we were all blown away. We had a lot to choose from, and indeed Zoe eventually made a work called Downtown (for Douglas) that comprises the eleven photographs used for the book—the ten used as chapter dividers plus the cover photograph—and added six “outtakes.” The suite of seventeen photographs was shown in the Buchholz Galerie exhibition that launched the book last fall. Zoe’s photographs add a geographical dimension to the organization of the book along with the roughly chronological one. And yes, indeed, I am an inveterate user of public transportation, and I move about the city a lot. Subways were also a locus of a lot of cruising in the 1970s. I wish I’d included an account in the book about picking up a guy on the subway who for some reason had keys to the subway bathrooms. Believe it or not there were still bathrooms in the subways in the 1970s, but they were locked and no one used them, so this guy had access to what were essentially private places for sex throughout the subway system!

Alawadhi: Downtown (for Douglas) has a really nice ring to it. Maybe it should be the title of another project. You mention in your memoir that much of your early writing was devoted to women artists such as Lynda Benglis, Hanne Darboven, Eva Hesse, Joan Jonas, Agnes Martin, Dorothea Rockburne, Pat Steir, and Hannah Wilke. Yet there were also so many women, close friends, colleagues, seniors, etc. who had a remarkable impact on your life. Some of these names include Linda Lindeberg, Helen Tworkov, Diane Waldman, Elizabeth C. Baker, Veronica Geng and Helene Winer. What did this gender dynamic mean for you? Was it coincidental?

Crimp: It wasn’t coincidental at all. I’ve had close relationships with women all my life. Funnily enough, when I recently did a reading from Before Pictures at the National Gallery in Washington, a woman got in touch with me by email beforehand to tell me that we had been friends in elementary school and that she now lived in Washington and planned to come to the event. My elementary school days were, needless to say, a very long time ago, but I do have a recollection of this woman—or rather little girl at the time—being a playmate. I think I preferred girls’ games to boys’. A great many of my good friends have always been women. By devoting myself to art by women, which in the early 1970s did not receive nearly as much attention as art by men, I could declare my solidarity with them: they were outsiders, and I felt I was acknowledging that I too was an outsider. Moreover, it was through my friendships with women artists—particularly Pat Steir—that I began reading second-wave feminist writing and finding that its critique of patriarchy spoke to me and my situation as a gay man. This would have been around the time of Stonewall; it would be a few more years before gay liberation writing began to appear. I didn’t consciously set out to devote my critical writing to women, but if I look over my career as an art critic, I have done so—there are essays on, and interviews with, Cindy Sherman, Sherrie Levine, Mary Kelly, Louise Lawler, Yvonne Rainer, Trisha Brown, Tacita Dean, Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker. I curated an early exhibition of Agnes Martin’s work. I edited the first book about Joan Jonas’s work. And why not? They are all great artists.

Douglas Crimp, Cindy Sherman, and Robert Longo, 1977 (Photo: Helene Winer)

Alawadhi: Can we discuss race in your memoir? What did that mean for your queer community at the time? I also want to tie this in with your thoughts on Baltrop’s photos of the piers and the fact that queer youth of color used to socialize there (esp. Christopher Street Pier) before the location’s closure in 2001 to make it part of Hudson River Park. I want to discuss the afterlives of these locations that were central to gay liberation but have also taken entirely different meanings, particularly for people of color and homeless people.

Crimp: Racial and ethnic difference figured in important ways in my life during the period I write about, but, at the same time, I lived in a relatively segregated world. I grew up in an all-white, indeed almost all-Protestant town in the Northwest. Then I went to college in New Orleans, a majority black city. When I moved off campus from Tulane, it was to a mixed-race neighborhood—or more accurately, since there was no such thing at that time in New Orleans, a white neighborhood that was directly adjacent to a black neighborhood. But my college had almost no black students. Tulane was first integrated during the time I was there. (Paul Tulane’s endowment stipulated that the college be for whites only.) The places that I remember being truly integrated were some of the gay bars that I began frequenting in New Orleans. For whatever reason—maybe because of the homogeneity of my hometown—I was especially attracted to people who were different from me. As you know from my book, my first serious boyfriend, Christian Belaygue, grew up in Casablanca and had an Algerian mother. But his real difference from me was that his culture was so thoroughly French. His name, after all, was Christian, he didn’t speak Arabic, and his memories of his mother from his childhood seemed to be mostly about going with her to European spas. Years later, in the darkest days of “actually existing Communism,” he and I traveled together to Czechoslovakia. He insisted that we visit Karlovy Vary, the grandest of the old European spas. I think this was in deference to his mother. It was a fairly grim place in those days. I mention a few other boyfriends in the memoir, including Juan Fernandez, who is Dominican, and Jonathan Green, who is African American.

When Guy Hocquenghem was staying with me in 1973, he and I went almost every night to Peter Rabbit’s, which had a predominately black clientele. It happened to be only two blocks away from where I lived, so going there was convenient. Having come out in gay bars in New Orleans in the early 1960s, several years before Stonewall, I was used to gay bars having a mixed clientele—men and women, old and young, black and white, middle- and working class. People were thrown together because we were all despised by the society we lived in. I’ve always loved such places. In New York after Stonewall, gay bars proliferated, and many of them became specialized—sweater bars, leather and Levis bars, men’s bars, women’s bars, piano bars, Latino bars, and so forth. I guess you could say Peter Rabbit’s was a black bar, but it wasn’t exclusively so, and it seemed more like an “outcast’s” bar than anything else. For my own part, I always loved bars with a queer clientele (we didn’t use the word “queer “ then, but I think it’s appropriate). The kinds of queer places where I used to hang out have long since disappeared, victims of gentrification, the redevelopment if Times Square, and Rudolph Giuliani’s quality-of-life campaign.

The Greenwich Village gay scene that I write about has also long since disappeared. First AIDS destroyed much of gay sexual culture in the 1980s. The authorities closed baths and sex clubs, but bars simply lost their customers over time—many got sick and died, others were afraid and stopped going out cruising. At the same time, the Village became too expensive for most gay people to afford. The scene moved to Chelsea, on one hand, and the East Village, on the other. The Chelsea crowd was older, richer, and more conventional; the East Village was young and hip. Most of the people I met in ACT UP lived in the East Village. There was still a lively club and performance scene there in the 1980s and ’90s. But you’re right, there was an afterlife to the scene in the Village. Young people of color had long been hanging out on the piers—what was left of them, which was large, crumbling docks extending far out into the Hudson. These kids didn’t live in the neighborhood. They came from whatever neighborhood they did live in to find people like themselves. A lot of them were trans. The rich people who were gentrifying the Village beyond recognition hated these kids. They were loud. They didn’t “belong” there. The police harassed them. They resisted. They started an organization called FIERCE. It’s ongoing, but I’m afraid the piers along the Hudson in the Village have become the publicly subsidized front yards of the super-rich who live in the Richard Meyer – designed residential towers on West Street. The kids of color don’t stand much of a chance in such a situation. And where can they go? It’s a place with a rich history—their history. And mine, too. For many years I hung out there, both at the piers and in the mixed-race bars on West Street. But it ended for me with AIDS. And now I rarely even go to Christopher Street, the main drag of the 1970s Greenwich Village gay scene, a street I must have walked up and down a thousand times. The Leatherman is still there. It’s a gay leather and fetish store that pre-dates Stonewall. It celebrated its fiftieth anniversary in 2015. The New York Times published an article about it. Its survival on Christopher Street, like the survival of the kids of color hanging out at the piers, seems like a miracle amidst all the designer clothing stores and fifty-million-dollar apartments. Such is New York City these days. Writing Before Pictures was a way of recapturing some of it for me.

Alawadhi: You write in your memoir that one constantly “learns how and where to be queer, since being queer is a matter of a world you inhabit, not something you simply are.” In light of the recent election results and the current political climate, do you have any advice for the younger queer generations on learning how and where to be queer again?

Crimp: There are always queer scenes, now, I think, even in smaller cities and more rural places. And there will likely be more reason than ever for people to come together for political resistance, around queer and trans issues, sure, but around just about everything progressives have fought for since the time I write about in Before Pictures, when it was still illegal in most places to have homosexual sex. I worry for so many people: immigrants, Muslims, all people of color, poor people, elderly people, people who will lose their health care. I worry about growing authoritarianism around the world. I worry about climate change. What we are facing is a crisis. We faced one in the 1980s with AIDS. It was a nightmare, but there was consolation in the way we came together to fight for our survival. That will have to happen again.

Hend F. Alawadhi is a PhD candidate in the Visual and Cultural Studies Program at the University of Rochester and a translator at Refugees Helping Refugees.

Before Pictures by Douglas Crimp. Dancing Foxes Press/University of Chicago Press, $39.

308 pages | 166 b&w and color plates | 6 x 9 1/2 |

© 2016