Answer Louise Lawler’s question in October: “What would Douglas Crimp say?” Or, to follow the title of Lawler’s exhibition: Why Pictures Now?

Pictures, for me, always—pictures, and poems (which hold on to ambiguity in the same way that pictures do). Pictures, because never once have I not stumbled over my words. Ever have I said not-precisely-the-thing-I-wanted and ached over the disconnect between my own heart and mind and mouth. Pictures don’t settle, and don’t ask us to. So, I can keep on trying.

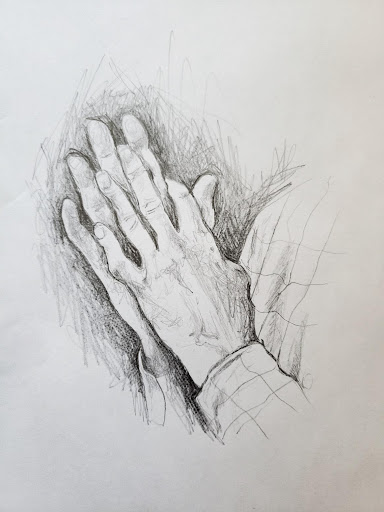

I don’t know what Douglas would say—despite all the essential things he said, I picture him listening more than I picture him speaking. But his marvelous hands would be flying!

Imagine an alternative space to museums. Describe what this space might look like.

Pathways forward, upward, and out. Choice, and the choosing. Jealously-guarded nothing. Encounters that cost nothing. Delight in one another (we’re all each other’s teachers). More places to sit, more places to rest. Willingness to give things up, and have it hurt a little.

Share an anecdote or memory you have of Douglas. Or, if you had the opportunity to share anything with Douglas now, what would it be?

After I moved to New York, I bumped into Douglas with nearly as much regularity as I had in the art history department at Morey Hall. I encountered him in museums, or moved in his wake, with the testimony of his signature in gallery logbooks, one or one hundred lines above mine. We ran into each other on the street near Old St. Patrick’s, around the time his Alvin Baltrop show opened at Galerie Buchholz. I had a postcard from the show tacked to the pinboard behind my desk at the Whitney—bare bottom, orange haze, and the Hudson River in the distance. I can see the river from my desk, and at sunset it sparkles, just like that.

I was unready for every conversation and encounter I ever had with Douglas. I didn’t know enough, or I didn’t say enough, or I didn’t ask the question I wanted to ask. The last time I saw him in person was in the fall of 2018, when Barbara Hammer delivered “The Art of Dying (or Palliative Art Making in the Age of Anxiety)” at the Whitney. I’d rushed downstairs to the lobby to pick up my ticket for the talk, late, after losing track of the hour at my desk. So I was flustered, and probably sweaty, when I threw myself into a seat behind Douglas, who turned around and smiled, looking so different from the last time I’d seen him. The talk was starting, but he stood up and there was an awkward, gentle hug across the theater seats between us. “I’m very glad to see you.”

Now, from my desk, I can see David Hammons’ Day’s End rising from the river—massive, empty, and sly—at the site of old Pier 52, and a legend. I wonder what Douglas would think of it. I wonder what project(s) would have absorbed him if he’d been here with us during the pandemic, and I think about how much he would have missed dancing, with friends. After almost six years in the city, I want to tell him I’ve survived it (am surviving it!)—that New York is my home (as he promised), and I’m finally ready to talk about it with him.

In Before Pictures, Douglas describes navigating between academia, life outside, and how each informs the other. Discuss leisure, and how academic work reflects personal life, or vice versa.

I hightailed it out of academia before I could discover much about its relationship to life outside (I had to get outside!). But I imagine those faulty barricades are not unlike the ones I trip over as a museum worker.

Outside my cherished circle of colleagues-who-are-friends, I’m not close with anyone who works in the arts. Most of the people I love don’t know much at all about the work that I do (which, for the most part, is how I like it). In this way, I maintain perspective on what is an emergency, and what is not. I am reminded that though I may love art to bursting, it will never love me back, won’t nourish every single one of my needs. That art matters a lot, but it doesn’t matter the most.

I have asked colleagues returning from holiday how they enjoyed their time away, and listened as they nervously, giddily disclose, “I didn’t see any art!” It is my favorite answer. I practice saying it, myself, and become more and more sure of it.

Share academic models that might push against linearity. Academia tends to be fairly linear, while dance is often fluid (unless it’s a line dance). Translate the linearity of academia into the non-linearity of a dance, and then transpose that non-linear dance back into the “linear” form of a diagram. In brief, submit a response as a score for a dance piece, or provide a diagram for a dance.

Is academia linear? I’ve always thought of it—as I think of most things—as circular. For better or for worse, do we not make our returns?

In his Dance, Art & Film course, Douglas used to show a famous sequence from La Bayadère—“The Kingdom of the Shades.” In an opium-induced dream, Solor reunites with the dead Nikiya, and they greet one another under the stars, surrounded by spirits. Thirty-two shades—the ghosts of other bayadères—fill the stage slowly, emerging one-by-one from darkness in a line that zigzags down an incline, and downstage. Arabesque penché, once, twice, thirty-two times. It is pure repetition, and if it doesn’t capture you completely, then ballet may never be your friend. Because pure repetition is what ballet ultimately is. Or something like that—Douglas said it better.

Pure repetition. Practice moves us forward, but it is also its own glorious end.

In the spirit of Douglas’s work with ACT UP: How do you understand the relationship between activism, arts, and academia?

I’m learning this terrain, gingerly testing its contours and creases; flailing, at times, over its harder edges. I have no broader understanding of it, yet, but particular points are clear to me. I’ve been told it’s the role of artists (and not art workers, though they are often artists too) to make a stand, to say what they know is right or to object to what they know is not. To make space for activism in art’s world (is this different from the world-world?). No. No! A hard edge.

Joy and friendship have helped me learn what activism is and can be in my world (the world-world). Joy and friendship have also made it possible to hold rage and grief and exhaustion all together (and have all together made us more powerful). In our fields and in our institutions, unions and mutual aid and collective action are critical ways we can care for one another and affect positive change.

Draw a Picture.