Revolutionary Love1

In the summer of 2008, a crowd of seventy-five to one hundred volunteers gathered at the Republican and Democratic National Conventions to read a text produced by New York-based performance artist Sharon Hayes. Entitled Revolutionary Love: I Am Your Worst Fear, I Am Your Best Fantasy, the performance opened with a sound test and an address to an unnamed lover: “Test, test, test. My sweet love, I know it’s been a long time since we’ve seen each other, and this isn’t the best time to reconnect.” Presented as a letter addressing personal and political desires of the “I,” the text is a chronological narration of a troubled relationship within the larger context of an unspecified revolution. Unlike many of Hayes’s other performances, Revolutionary Love’s narrative does not specify a particular historical moment. From the limited amount of information the text discloses, we can only tell that there is a discrepancy between the speaker and his or her lover’s attitude toward queer revolution, evolving from phrases like “this is the moment to act” and “when we were shouting revolution,” to “you said I am too loud, too opinionated, and too gay” and “you told me I am stuck in the past.” It is through the course of the performance’s revolution and unfolding––its short-lived climax and its sudden disappearance––that we sense an affective response of both rapture and loss.

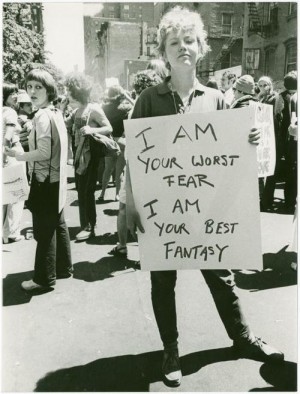

Figure 1. Donna Gottschalk holds poster “I am your worst fear I am your best fantasy” at Christopher Street Gay Liberation Day parade, 1970. Image courtesy Diana Davies photographs. Manuscritps and Archives Division. The New York Public Library. Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.

Drawing its inspiration from a slogan created for the first Christopher Street Liberation Day parade in 1970––“I am your worst fear, I am your best fantasy”––the subtitle of Revolutionary Love leads us to a moment captured by photographer Diana Davies that day. In this picture, a woman named Donna Gottschalk holds a hand-lettered sign with the aforementioned slogan. Looking proud yet uncertain, the emotional ambivalence on Gottschalk’s face is the dust of memory that we must brush off in order to tell the story of a moment buried in history. My description of the photograph must stop here and enter the realm of interpretation precisely because there’s nothing indexical to describe beyond the physical composition of Gottschalk and the other paraders, the equally ambivalent glance cast by the woman behind her, and the length of their shadows indicating at what time of day this picture might have been taken.

The unspecified past tense in the narrative of Revolutionary Love and its demand for a “new beginning” narrates a fictional story inspired by Davies’s photograph. The seemingly random choice of locations (“I am Your Worst Fear” performed at the Democratic National Convention and “I am Your Best Fantasy” performed at the Republican National Convention in 2008) and the decision not to perform at Christopher Street indicates that the performance is not a historical reenactment but speaks Revolutionary Love’s forceful statement: even though “this isn’t the best time to reconnect,” “my” voice has to be heard right here, right now. As Michel de Certeau states: “narrated history creates a fictional space. It moves away from the ‘real’— or rather it pretends to escape present circumstances: ‘once upon a time there was…’ In precisely that way, it makes a hit (‘coup’) far more than it describes one.”2 What de Certeau means by “coup” is a violent and sudden seizure of power that is able to disrupt history and subvert dominant structures. My proposal to use the word “coup” to understand Revolutionary Love’s relation to space and time also aims to suggest its subversive and insurrectionary potentials. The narration of Revolutionary Love should be understood less in terms of its content than its tactical move to balance the power between its speakers and the circumstances they inhabit. Here the circumstances that Revolutionary Love attempts to alter is what was posited as the “issues at stake” for the 2008 U.S. presidential election––namely, the Iraq war and the financial crisis. If the economy and warfare are prioritized in modern democracy, then the discussion about love and queerness raised by Hayes could indeed be seen as untimely and preposterous. However, by counterposing love to the power of money and war, Hayes not only deconstructs boundaries between personal and political, but also deploys at once reason and passion in her revolution. Although Revolutionary Love feigns an escape from the circumstances of the 2008 election and tells a story of “once upon a time” between two lovers, within this fictional space we are able to articulate a critique of our contemporary moment. This is also where the content of Revolutionary Love’s text conjures its form, as the speaker critiques the tendencies that “people always say in a moment of crisis, the path of wisdom is far better than the path of emotion.” In so doing, Revolutionary Love abruptly places our affective lives in the midst of the political issues of the financial market and Iraq and revives the emotions that capitalism attempts to disavow, alienate, and exclude.

Harry Jiangtao Gu

PhD Student, Visual and Cultural Studies, University of Rochester

- This blog is a part of my longer essay “From the Event to the ‘Not-event,’ The Queer Tactics of Sharon Hayes,” in which I discuss Hayes’ performance in relation to 1970s history and the differences between her performances and installations ↩

- Michel de Certeau, “Story Time,” in The Practice of Everyday Life, trans. Steven F. Rendall, (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, 1984), 79 ↩