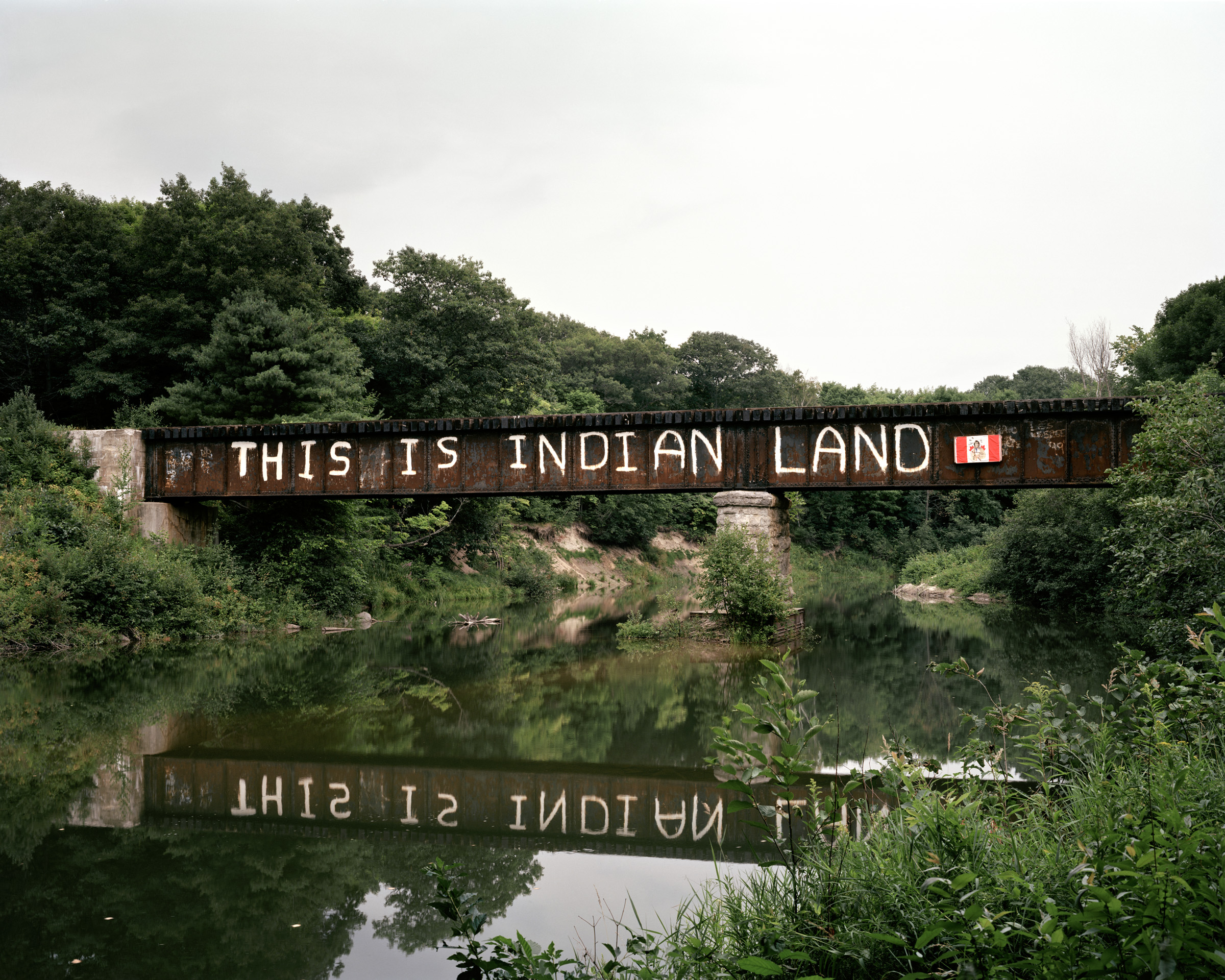

Artwork by Andreas Rutkauskas, 2016.

The subject of my work focuses on landscapes that have been affected by technology. This may refer to physical alteration of a landscape, or the psychological effects of such changes. For example, my recent projects have addressed the cycles of industrialization and deindustrialization in Canada’s oil patch (Petrolia, 2013), the impact of Internet-based research on wilderness recreation (Virtually There, 2010-15), and the subtle technologies used to survey the Canada/U.S. border (Borderline, 2016). While my medium is principally photography, I acknowledge the limits of photographs in articulating the experiences of being in a landscape. Therefore, I often incorporate other media such as video into my research in order to provide the viewer with a more holistic perspective.

Stretching 8,891 kilometers from Tsawwassen, British Columbia, to Campobello, New Brunswick (including 2,475 kilometers shared with Alaska), the Canada/U.S. border is the longest shared land border in the world. This line travels between town sites and wilderness; it is also visibly demarcated by a six-meter-wide swath of cleared land amongst the forest, and over 5,500 granite and steel, as well as concrete obelisks called “monuments.” While this border is often referred to as undefended, it is nonetheless heavily monitored under surveillance technologies. Both the Canadian and U.S. governments utilize CCTV and thermal imaging cameras to scrutinize the border. Additionally, ground sensors are embedded under the roadways leading to dead ends, providing situational awareness for both the U.S. Border Patrol and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). My project Borderline features images of locations where official crossing points used to exist. Some of them are now barricaded, often in very primitive ways. At more remote locations, a no entry sign, rusted wire fence, or fallen tree is all that separates one country from the next. While my images do not depict U.S. or Canadian border patrols, many of the photographs were taken shortly before or after the encounters with these officials. Often within a short period of my arrival at these locations, and occasionally, even prior to my arrival, a field unit would be dispatched to investigate. After the officials get to know my intent, they would move the vehicles out of my frame, so I could make the shot. However, this process is only part of what leads to the appearance of the border being so porous in my work. There are of course many places where I did not encounter anyone, where I could walk for hours along the denuded cutline that separates the two countries without impediment. Even though the security measures discourage humans from lingering at the Canada/U.S. border, they cannot fully control the vast territories of the borderlands.

Following the attacks on the World Trade Center in New York on September 11, 2001, policies surrounding migration and daily traffic along the border changed dramatically. The Québec town of Stanstead is one poignant example, where architecture and infrastructure straddle the boundary, but there are many more complexities along the divide, including the U.S. enclaves of Northwest Angle and Point Roberts, 0 Avenue in British Columbia and Washington State (a roadway acting as the de facto boundary), and a number of sovereign First Nations territories. The photographs in Borderline establish a pastoral landscape that is typical of the North American frontier. These pictures stand in contrast to our collective imagination surrounding the term “border,” which conjures up imagery of more heavily militarized zones of separation such as Israel’s Green Line, the Indo-Pakistani Line of Control, or the De-militarized Zone (DMZ) between South and North Korea.

- International Peace Garden

- Looking into the Okanogan National Forest

- Monument to Monument

- Chief Mountain Port of Entry

- Cutline near Cultus Lake, British Columbia

- Pigeon River Border Crossing Station

- Sault Ste. Marie International Bridge

- Abandoned Crossing, Big Beaver, Saskatchewan

- Monument #276 Waterton Lakes, Alberta

- Mulholland Point Lighthouse, Campobello Island, New Brunswic

- Port of Entry, Snowflake, Manitoba

- Monument #120 Chilkoot Pass, Alaska

- Garden River First Nation Andreas Rutkauskas

- Monument #4 Tsawwassen, British Columbia

- Improvised Barricade

Copyright © 2017. Andreas Rutkauskas. All rights reserved.