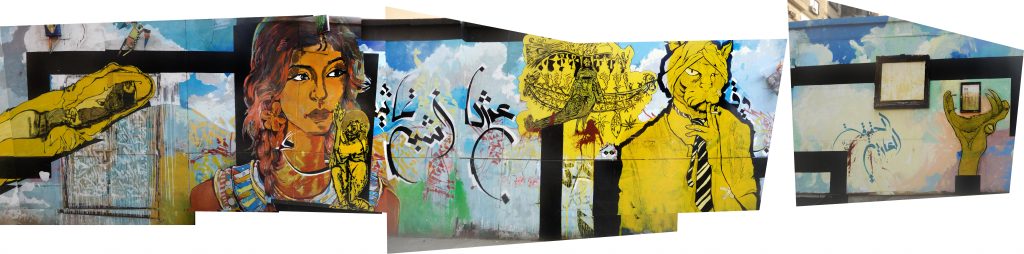

Figure 1: Multiple artists, Egyptian Identity, June-July 2013, paint, spray, metal, found objects, and wood, 82 ff x 13 ft (25 m x 4 m). Qasr El-Nil Street, Cairo, Egypt. (Photograph: Abdelrhman Zin Eldin)

A mural 25 meters long and four meters high stands at the end of Qasr El-Nil Street in downtown Cairo, only three blocks away from the famous Midan El-Tahrir (Tahrir Square) and Mohamed Mahmoud Street where Egyptian protestors lived and died demanding the fall of the regime starting on January 25, 2011. The sunset sky of white and blue with hints of red and orange forms the background for a portrait of a young fallaha (rural) girl with flowers in her braided hair, looking into the distance contemplating her past, present, and future. Beside her is a poem: “When I first opened my eyes, and before my mother knew me, they applied kohl (eyeliner) to my eyes reaching my temples so I can look like your statues.”1 She is surrounded by metal sculptures, hybrid figures, human and non-human, with legs and wings. To her right are three picture frames that create a domestic setting.

This is the first iteration of the mural Egyptian Identity or Reclaiming Egyptian Identity that artist-activists Ganzeer and Ammar Abu Bakr were informally commissioned to paint by Merit Publishing owner Mohammed Hashem on the parking lot wall across from his office on Qasr El-Nil Street.2

Qasr El-Nil Street connects Midan Talaat Harb (Talaat Harb Square) with the National Democratic Party headquarters, the Egyptian Museum, and the Arab League building. It is no more than a ten-minute walk from Tahrir Square and three streets away from Mohamed Mahmoud Street. Yet, it is a far less famous site of the Egyptian revolution. It has seen fewer battles and bloodshed and is rarely mentioned in stories about the first eighteen days of the revolution or the months after. But mural and graffiti artist-activists know it well and have—since the revolution erupted—marked it often. Because of its location on the periphery of revolutionary visual culture production in downtown Cairo, the Qasr El-Nil mural was witness to more activity from June 2013 to November 2015 than Mohamed Mahmoud Street and other more highly surveilled locations. This made it possible for artist-activists to revisit this wall, mark it, and engage with it in ways that were impossible in other sites. Therefore, the Egyptian Identity wall provides us with insight not found anywhere else of the Egyptian revolution, documentation of events, and artist-activists’ ways of negotiating and resisting changes and crisis during these two years of rapid transition.

Despite the sustained activity on this wall, the Egyptian Identity mural has not received much attention in scholarly or popular writings on graffiti and murals of the revolution. Mona Abaza, professor of Sociology at the American University in Cairo, a primary scholar on this form of visual culture production, focuses mostly on Mohamed Mahmoud Street, temporary separation walls erected in streets leading in and out of it, and the role graffiti and murals as documentation and barometer of the revolution.3 Suzee in the City, Soraya Morayef’s blog, provides detailed and inclusive documentation of graffiti and murals and interviews with artists, but does not have a post on this mural.4 And Georgiana Nicoarea’s scholarly writings provide a rich examination of the relationship between Egyptian identity and graffiti through close readings of colors and poetry, but she has not written about this particular mural.5 Most writings that do engage with this mural do so in passing, within a text on graffiti and murals generally, or focus on a singular snapshot of this mural. For example, in the edited volume Walls of Freedom there are two notes that describe the mural and provide some context for it.6 Elsewhere, Angela Boskovitch tells the story of the mural’s first iteration shortly after it was finished.7 This article aims to fill this gap by shifting the attention to the periphery and make apparent the significance of the Qasr El-Nil Street wall as an example of artist-activists’ use of fringe spaces for collaborative work of dissent.

The January 25, 2011 revolution brought to the forefront a number of crises that continue to affect Egyptian society at all levels. One such crisis is a crisis of the state where corruption, nepotism, and state sanctioned violence against minority groups has become all too common. Another example is that of religious, class, and gender divides that plays out in acts of violence perpetrated by those who have the upper hand over women, Christian Copts, the poor, queer, and other marginalized people. Throughout the revolution, mural and graffiti artist-activists engaged with these crises by claiming city walls to debate and articulate their opinions and present alternative realities, a dynamic that has been examined by several scholars. Mona Abaza writes of Ammar Abo Bakr’s murals as “one main way of both defending and occupying the street. [They were] a way to conquering the space in a situation of war…”8 Georgiana Nicoarea argues that graffiti of the revolution recovers poetic and artistic pasts in order to “reterritorialize” graffiti as an artistic and cultural production of the revolution.9 This contribution expands on this body of scholarship by interrogating the crisis of access to the street and public space as sites of demonstration, creation, collaboration, divide, and violence.

This crisis of access to public space has become manifest in laws and changes in social behaviors. For example, shortly after the Supreme Council of the Armed Forced (SCAF) took over state affairs on February 11, 2011, they made demonstrations illegal and enforced a curfew.10 Another example is a law proposed on October 30, 2013 by Interim Minister of Local Development Adel Labib to penalize graffiti and street art with up to four years in jail and a fine of 100,000 Egyptian Pounds ($12,770).11 Graffiti and mural artist-activists have been arrested under other laws, such as environmental protection and pollution, and defacement of private property.12 Without a law addressing street art and graffiti explicitly, artist-activists have been accused of crimes ranging from vandalism of public property and environmental pollution that carry a fine and sometimes a prison sentence, to crimes against the state, which may be punishable with a long-term prison sentence or even death. Because of these conditions, I argue that the Egyptian Identity mural presents an example of graffiti and mural artist-activists’ engagement with and resistance to the ways the street has become increasingly policed since June 2013.

At the end of June 2013, this long and high wall with a two-panel metal door and a wooden commercial billboard became the site for a unique collaborative mural that has seen many changes during its life. Most modifications took place from June 2013 through mid-2014. During this period, Egypt was witnessing major shifts in the political sphere as the management of state affairs moved from the hands of the Muslim Brotherhood into those of the military. Thus passing between two institutions that are seen as counter-revolutionary. Artist-activists of the Egyptian Identity mural engaged and resisted the confusion and violence created by these changes through reclaiming their rich past and present Egyptian identities, making public their awareness of the complexities of their political lives and proposing alternative imaginaries in which religious and class divides, as well as violence are markers of a time past.

Throughout this essay I use the term artist-activists to describe the individuals who participated in the Egyptian Identity mural because it best describes the intention behind their participation and engagement with public ephemeral visual culture production on city walls. When I first began thinking through graffiti and murals of the Egyptian revolution, I referred to the individuals who created these works as artists. But the term conjures complex meanings of art as separate from daily life; i.e. a practice that aims to be exhibited, theorized, and critiqued through the art world and art history. The individuals who created these works used visual mediums autonomously as their way of participation in the revolution in order to document and make legible daily happenings they witnessed and were part of. Their intentions were not bound by art history or art worlds. Rather they were bound by their commitment to participate in a local, national, and regional social movement as citizens of Egypt and inhabitants of Cairo. I do not use the term street artists because street art is a category that is too large to allow for the specificity of those who marked city walls with paint and spray. Therefore, the term artist-activists aims at situating graffiti and murals, as well as their creators within a space of praxis where ideas and actions collide at the moment of social and cultural unrest and political crisis.

This essay focuses on four photographic moments of this mural’s life to demonstrate how the process of creating it reflects artist-activists’ experiences with, ways of engagement, and resilience to crisis. I contend that the collaborative process in itself is a tool of dissent. Despite constant increases in surveillance and the introduction of anti-demonstration laws, the process of mural-making brought artist-activists together to express their opinions in public. I have chosen to follow the mural through these particular snapshots because these iterations reveal the kinds of pressures and confusions that artist-activists were feeling during those moments, their processes of collaboration that adapt to swift changes in conditions, and the forms of resistance utilized during these months of social and political crisis.

Photograph I: July 2013

The mural’s focal point is a portrait by Ammar Abu-Bakr of a fallaha girl marked by her thick and loosely braided hair, kohl outlining her eyes. She is wearing a Nefertiti-inspired necklace. To her right is a poem by Ahmed Aboul-Hassan written in calligraphy by Sameh Ismael. The poem refers to a rural tradition where kohl is applied on the eyes of newborn babies to connect them to their pharaonic history and keep away envy. At the far right of the mural, there are three picture frames made by Noura Nassel and Jan Nikolai. Two of the frames show faded photographs of fields of wheat, a commentary on food scarcity in Egypt.13 The third frame contains a photograph of a wooden chair in a grassy meadow. Between the frames and the poem is another calligraphy that reads: “the naked truth.”14 The mural has three-dimensional elements made by Alaa Abdel Hamid. They are made of metal from discarded car parts, wire, and paint and were originally used in Abdel Hamid’s first solo exhibit, The Solution is the Solution, in 2011.15 The title of the exhibition is a play on the Muslim Brotherhood’s famous slogan “Islam is the Solution.”16 Each sculpture is a mix of human and non-human features, with legs, faces, wings, antennae, long necks, and metal bodies. They seem to be in motion, some are hovering just above the mural, while others are climbing up the wall. There are also four gypsum eagles—as seen on the Egyptian flag—hung upside down at the center of the mural.

Figure 2: Multiple artists, Egyptian Identity (detail), June-July 2013, paint, spray, metal, found objects, and wood, 82 ff x 13 ft (25 m x 4 m). Qasr El-Nil Street, Cairo, Egypt. (Photograph: Abdelrhman Zin Eldin)

When I first encountered this mural, via photographs posted on blogs and social media, I found it beautiful and traditional in its form and content. Except for the upside down gypsum eagles, the mural appeared to be a tribute to Egyptian history and seemed to be a departure from the overtly confrontational works that covered Cairo’s walls since January 2011. Contextualizing this mural within the political and social moment of its creation will allow for a deeper understanding of its significance.

This mural was being painted while President Mohamed Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood was facing criticism from many Egyptians who were becoming increasingly impatient with his ineffectiveness and lack of response to revolutionary demands. At the time, the military tribunals for civilians were still ongoing, figureheads of the old regime were still free and some continued to hold positions of influence. These and other issues made it clear that President Morsi was lacking the skills needed to shift things around to effect change. Simultaneously, access to public space was being increasingly policed by the military and vigilantes of the Muslim Brotherhood who felt they had legitimate power over civilians. In order to mediate these conditions, mural and graffiti artist-activists’ opted for subtle messages that required a level of savviness and time to understand. By centering the mural around an unveiled rural girl and connecting her to pharaonic statues, Abu Bakr and Abu ElHassan make an argument for the legitimacy of pharaonic statues that the Muslim Brotherhood was trying to ban and destroy as unethical. In doing so, they remind viewers that the statues are part of Egypt’s glorious past, as well as its current traditions.

In order to avoid the dangers of engaging with street art, which had become punishable by anti-demonstration and anti-assembly laws, artist-activists secured the permission, albeit informal, from the parking garage attendants through Merit Publishing’s owner Hashem, whose office has been on this street for the past fifteen years. They also worked around the clock and finished the mural within four days. In order to accomplish this, they brought together a large number of artist-activists to help prepare the wall, mix colors, paint, and assemble the various pieces. They also assigned street watchers to keep a lookout for any police.

Even though the mural’s messages are subtle, they reflect a sense of anxiety caused by the confused present and unknown future, while simultaneously giving a sense of hope for alternative futurities. The poem celebrates a rural tradition of ornamenting the eyes of new born babies eyes to connect them to their rich pharaonic past where statues’ eyes were highlighted by outlining them with black paint. At the same time, the poem has a hint of reproach toward this tradition that keeps children bound to their past, as static statues, rather than propelling them forward into different futures. The hybrid-creatures have a robotic aura and they seem to be running up the wall as if trying to get over it to the other side. These figures’ bodies, appearing weightless while frozen in motion, can also be understood as forms of resistance to staying put.

The frame with the serene lone wooden chair in a grassy field looks like a window to something beyond the wall. As if the side of the mural that we see is indoors and the chair is what one sees when looking outside. The locked door hidden behind layers of paint instigates a desire to unlock it, to see what lies behind as if it were a door to a secrete garden. The window-frame and the door create an imaginary of worlds beyond this one that have the potential to be greener and calmer. These imaginaries are the artist-activists’ forms of refusal to submit to crisis conditions that demand they either remain static or destroy their beautiful histories. Rather, they put forth a hopeful public message that alternative futures are possible if only one dares to dream.

Photograph II: December 2013

On December 21, 2013, I met Egyptian Identity in person as I walked for the first time ever down Qasr El-Nil Street searching for it. The day was cold and the streets were empty. I took advantage of the little human and car traffic to spend as much time and take as many photographs of the mural as I could. A city of twenty million inhabitants was not as busy as it typically would be. But little in Cairo and Egypt was typical at the time.

Figure 3. Multiple artists, Egyptian Identity, August-November 2013, paint, spray, metal, found objects, and wood, 82 ff x 13 ft (25 m x 4 m). Qasr El-Nil Street, Cairo, Egypt. (Photograph: alma aamiry-khasawnih)

On June 30, 2013, and after months of tension over the disappointments in President Mohammed Morsi’s leadership, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) took over the running of Egyptian state affairs again by overthrowing the president. As a result, thousands of Muslim Brotherhood supporters took to the streets and occupied squares in demonstration of this coup/takeover. On August 14, 2013, at 7:00 AM, military bulldozers entered the Rabaa and Nahda Square camps in Cairo where thousands of Muslim Brotherhood supporters had been holding out since June 30. With tear gas and live ammunition, the SCAF ended the sit-ins. As news of this spread, Muslim Brotherhood supporters all over Egypt attacked police stations and set fire to several churches, Christian institutions, and homes. At the end of it all between six hundred and one thousand people were killed, almost four thousand individuals injured, and military general Abdel Fattah El-Sisi was instated president.

Shortly after the massacre in Rabaa in August and until November 2013, Egyptian artist-activists went back to the Egyptian Identity mural with bold colors and more direct messages of anxiety and sadness. A black line, drawn by Nazeer and El Zeft, zigzagged through the mural as if creating a wormhole throughout its various elements. This thick line resembles an underground escape route. The black line also looks like a mourning band that is usually tied around the upper arm when a group of people are mourning a collective loss, thus suggesting that Egypt is grieving those killed in Rabaa.

Citizen Maw, a hybrid cat-human,drawn by Ganzeer is wearing a cuffed button-up shirt and a loose tie with a farmer’s headdress of Upper Egypt. Maw is smoking a cigarette, a red slash runs through its eye and bandages cover wounds on the side of its mouth and arm. These injuries suggest a recent fight. Citizen Maw’s professional look speaks to Egyptians trying to fit into the politics of respectability as modern and global citizens engaged in global trends. Yet these politics are in conflict with the iconic traditional headdress of Upper Egypt. This region of Egypt is mostly rural and has the highest concentration of poverty. Citizen Maw’s embodiment of these identity conflicts highlights a tension of who is deemed truly Egyptian.

Figure 4: Multiple artists, Egyptian Identity (detail), August-November 2013, paint, spray, metal, found objects, and wood, 82 ff x 13 ft (25 m x 4 m). Qasr El-Nil Street, Cairo, Egypt. (Photograph: alma aamiry-khasawnih)

Also, the name Citizen Maw is not chosen randomly, but a strategic reference to Chinese revolutionary Mao Zedong (Chairman Mao). Although the name does not appear on the mural itself, it is found in interviews with Ganzeer. By calling the cat after Chairman Mao, Ganzeer is asking the viewers to consider the diverse meanings of Chairman Mao as an icon. Chairman Mao was a leader of the once underground Communist revolutionary movement in China and dictator of what is often thought of as a failed communist project. He is at once ideal and ruthless. Therefore, we can understand Citizen Maw as a symbol of the Egyptian elite who at face-value represent Egyptian modernity as they engage with illicit and failed dealings, while simultaneously holding on to rural traditions. These contradictions complicate Maw’s own relationship with himself as a citizen who is stuck between the past and the present, never quite fitting in or being accepted as fully Egyptian.

Another addition, drawn by Med Hamd Nasr Sodane, is a Ba, a bird-human hybrid. In ancient Egyptian pharaonic beliefs, the Ba is what makes each individual unique and is one of five parts of the human soul: Ren, Ka, Sheut, Ib, and Ba. The Ba is surrounded by Ankh (the key of life) and its neck is adorned with an Ankh necklace. The key of life is both a symbol of physical and eternal life and is often seen carried by gods and goddesses in tombs. Amro Okacha added a viper that is ready to devour the serene image of the chair in a grassy meadow. The snake in Egyptian mythology represents both the beginning and the end, good and evil, and is seen as the protector of all. Yet, here the viper is swallowing whole one of the few calm references in the mural. It looks evil and unyielding. If we understand the picture of the chair as a sign of a beautiful imaginary, then the viper is bringing that imaginary to an end, perhaps to be reborn at a later date.

Ammar Abu Bakr added an angel wearing a gas mask kneeling in front of the young girl, thus likening her to a goddess. The angel is similar to those found in Christian churches, thus creating a reference to Coptic Christians. The gas mask makes a gesture to unbreathable air, a fire. This is a reference to the violence perpetrated against Copts across Egypt. The kneeling angel is asking Egypt, symbolized by the girl, for help or forgiveness. To the left of the angel and the rural girl, Hanaa El Degham painted a man wrapped in burial shroud reminiscent of mummies and Muslim burial customs where the dead are wrapped in white cloth before being set into the ground. The representation of Muslim burial rituals is a commemoration to the hundreds of Muslim Brotherhood supporters who were murdered in Rabaa and ElNahda. Also the connection between ancient Egyptian mummification and Muslim burial rituals signals that those killed will return in the afterlife.

These additions are bright, confrontational, and coordinated. They challenge narratives presented in the first iteration of the mural, as well as build on some of the tensions seen in it. In the first iteration of the mural, symbols of Egyptian identities were articulated: rural beauty, calligraphy, poetry, and pharaonic iconography. Meanwhile, the second iteration demonstrates a more direct political message, as well as tensions and struggle over what constitutes an Egyptian identity. In this mural, the iconic cat and viper can be interpreted as ancient iconography that celebrates pharaohs’ cats and rebirth as the viper sheds its skin. They also can be understood as representations of a confused identity: the cat as both modern and rural, and the viper as swallowing happiness whole, perhaps to rebirth it again differently.

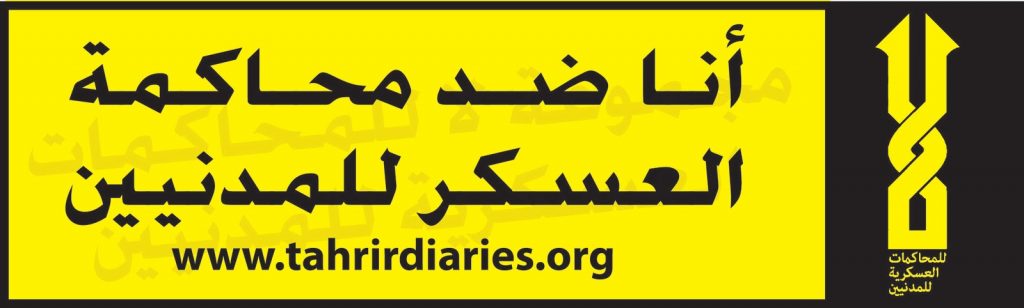

All additions in the second iteration use black and yellow. These colors are references to the No to Military Trials for Civilians campaign (Figure 5) and the logo symbol for the Rabaa massacre, which is the inside of the palm facing out, with the thumb tucked in and the other four fingers extended out all in yellow with a black background.

Figure 5: Tahrir Diaries, No to Military Trials for Civilians, sticker, various sizes. Retrieved from http://www.tahrirdiaries.org/.

The new elements engage with the previous works that came before them through additions and alterations without completely erasing or overwriting what was there before. The previous elements continue to be seen and remain legible, although their meanings changed. The second iteration of the Egyptian Identity mural presents a dystopic reality where death is common-place, life and death are interchangeable, and identities are confused and hard to decipher. Yet, in its ambiance of dystopia the coordinated and collaborative additions illustrate that the artist-activists are united in their position against military sanctioned violence and are aware of the military and the Brotherhood’s tactics that focus on dividing Muslims and Christians.

Photograph III: September 2015

Figure 6: Multiple artists, Egyptian Identity, January 2014-September 2015, paint, spray, metal, found objects, and wood, 82 ff x 13 ft (25 m x 4 m). Qasr El-Nil Street, Cairo, Egypt. (Photograph: alma aamiry-khasawnih)

When I returned to Cairo for a year of field work in September 2015, I went back to visit the Egyptian Identity mural. I found it frantic, confused, and overwhelming. Nazeer returned to the mural and filled the black zigzagging line with stencils of multiple icons of the Egyptian revolution. Such icons are: the state television building Maspeiro;17 cross and crescent put together to signal Christian and Muslim unity; machine guns; camels and tanks referencing the Battle of the Camels that took place in February 2011; raised fists; ladders; Facebook and Twitter logos to recall the use of social media during the revolution; KFC logo (this restaurant gave demonstrators food without charge while they camped in Midan El-Tahrir); logo for Creative Commons; A.C.A.B: All Cops Are Bastards; bicycles; awareness ribbons; a justice scale; the first aid sign; the number 74 within olive branches in memory of the seventy-four Ahli football club fans that were murdered by police in Port Said in February 2012; a throne; the word no; the number 18 for the eighteen days it took to remove President Mubarak from office; and a bra reminding people of the Girl in the Blue Bra who was beaten by riot police in December 2011. The black zigzag continues to emerge as a memorial band that carries reminders of the losses and wins experienced, acts of resistance, as well as of sources of oppression during the revolution.

The graffiti collective Mona Lisa Brigades added an edited version of their logo at the far right end of the wall.18 Their typical logo is Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa holding a spray can in a yellow caution sign. In this version, the Mona Lisa has morphed into a women who has more typical Egyptian features, her head is covered with a red veil, the lower part of her face is covered by a sheer scarf, she has an eyepatch on her right eye, and in her left hand she is holding a canister of insect repellant instead of the spray paint canister. By changing their logo from a standard signature to a unique work of in itself, the Brigades are reclaiming their own activism and calling on Egyptians to resist in more direct ways. The Mona Lisa has an eyepatch on her eye commemorating demonstrators who lost their eyes due to direct shots by snipers during clashes with the SCAF and riot police in November 2011.

The rural girl is now wearing a gas mask, added by Ammar Abu Bakr, as she joins the dystopic reality indicated earlier by the angel in the mask. The gas mask here not only indicates a wider reach of a bleak future, but also calls on Egyptians to join the ranks of the revolution. The gas mask was a foundational piece of gear worn by demonstrators that helped them breathe through the tear gas used by the police and military.

A head of a police officer in a riot helmet is peeking from behind the wall. This is El Zeft’s The return of the bastard. This piece illustrates how the police are now creeping back onto the streets after being rarely seen around the city in the past few months.19 To the right of the police officer is a stencil of Charlie Chaplin with the text “Thinking of the metaphysical is a waste of time!!!”20 Chaplin and the text have replaced the fields of wheat that were originally in the frame. The second frame now features an outline of human figures standing close to each other in a line. Chaplin’s portrait and the text accompanying it gesture to the absurdity of life at the moment this was added. The text suggests that thinking of grand ideas, such as a revolution, is a waste of time. But the exclamation marks at the end suggest that such a statement is in itself absurd.

Figure 7: Multiple artists, Egyptian Identity (detail), January 2014-September 2015, paint, spray, metal, found objects, and wood, 82 ff x 13 ft (25 m x 4 m). Qasr El-Nil Street, Cairo, Egypt. (Photograph: alma aamiry-khasawnih)

The ridiculousness of the situation continues as the space between Citizen Maw and the rural girl is filled with rats running through a rat maze. This maze and the rats point to the mundane sense of daily life where one is expected to run around accomplishing very little, while being unable to get out. There are also three figures in white, black, and yellow suits threatening to shoot a man whose body is a heavy block of concrete. One of the figures has a police/military heavy duty boot for a head that represents the military, another a monkey’s head, while the third sports a human head with a beard and a Mickey Mouse mark on his forehead representing the Muslim Brotherhood.21 The military and Brotherhood figures are pointing guns at the man who is unable to defend himself or run away because of his weighed down body. This addition articulates that the artist-activists are aware that the military and the Muslim Brotherhood are in alliance. In other words, neither the military nor the Brotherhood should be trusted to have the best interest of the Egyptian people in mind. Rather, both institutions are ready to execute whoever stands in their way. El Zeft describes the main crisis during which this iteration of the Egyptian Identity mural was being painted plainly and succinctly:

Now I came out of the blender, only to enter a grinder—one of military rule and religious rule. They’re fighting each other for power and I’m supposed to side with one of them, because otherwise I’m weak and a traitor of the revolution. Somehow, the revolution has become the pet subject of precisely those two factions, who do it the most harm. No—fuck both of them.22

This sentiment is supported by the various visual messages equating the Brotherhood to the military as counter-revolutionary institutions.

When I took these photographs that make up the above panorama of the Egyptian Identity mural in 2015, Egypt was undergoing increasing militarization: military personnel and armored vehicles had a frequent presence on the streets; individuals who spoke against the state whether online or traditional media were arrested; demonstrations, regardless of size, were met with excessive use of force; human rights activists were being prevented from entering or existing the country; thousands of surveillance cameras were installed in street cafes in downtown Cairo; and cultural and art spaces were raided and shut-down. A general sense of confusion and depression was setting in deeper. This was made worse by the general inability to plan because so much of what was happening was random and unpredictable. All of this is reflected in this version of the mural, where it is hard to tell where a story begins or ends, who is doing what to whom and why, and what is real and what is fiction.

Despite the punitive legal measures introduced since November 2013 making it dangerous to engage with graffiti and murals, artist-activists have gone back to this wall numerous times, putting themselves in danger in order to contribute to public conversations and tell their sides of the story. They continued to collaborate, spot each other, watch for threat, and work in teams. They insisted on keeping their sense of humor, albeit sometimes dark and depressing. They used this public space to think collectively and make visible tactics of counter-revolutionary agendas. In this iteration of the mural, artist-activists did not shy away from directly critiquing various state and independent institutions, such as the national television station, the justice system, the Muslim Brotherhood, police, and military. By adding stencils and figures referencing these bodies, artist-activists documented the complacency of these institutions in the violence that has been as is being enacted against Egyptians. Also, unlike earlier iterations where artist-activists worked in collaboration and coordination, the frantic nature of this version reflects the turmoil of the moment and difficulty to make sense of what was happening in Egypt.

Photograph IV: November 2015

On November 11, 2015, the Egyptian Identity mural was completely painted over with white paint. The wall was left clean without a trace of what lay beneath the thick layers of white paint.

This act of erasure was one of a series of acts of erasure and destruction against graffiti and murals of the Egyptian revolution. Only a few weeks before, the iconic wall of the American University in Cairo in Mohammed Mahmoud Street was torn down. In January 2016, just a few days before the fifth anniversary of the revolution, the wall of the French School, also in Mohamed Mahmoud Street, was painted white. In March, the graffiti inside the pedestrian crossing in Zamalek, an island in the Nile, was also erased.23

These acts of erasure signal a new crisis: the active expungement of history and the creative memory of the Revolution as embodied in graffiti and murals on the walls of Cairo. The organized demolition and removal of these forms of expression erases all traces of public dissent by Egyptian graffiti and mural artist-activists, making it appear as if nothing was ever there.

Conclusion

Through their collaborations, debates, additions, and layers of paint artist-activists said “fuck you” to the crisis of access to the street. Despite increased surveillance and under the threat of imprisonment, fines, and perhaps charges of treason, these individuals organized themselves, worked together, kept watch, and worked in shifts for hours in order to say what they had to in public. Perhaps chosen without much thought, the peripheral location on Qasr El-Nil Street allowed them to create, over a two year period, an Egyptian Identity that captured, illustrated, and unpacked diverse tensions and confusions, hopes and dreams, as well as utopias and dystopias that make them Egyptians at this particular historic moment. These artist-activists engaged with events and life experiences as they were unfolding before their eyes from June 2013 through November 2015. They did so while making connections to histories past and futures to come. In a way, they were making it hard not to simultaneously consider the past, present, and future of what makes them Egyptians.

Throughout the Egyptian revolution, artist-activists took to the streets, marked the walls, documented events, and proposed new possibilities. Some of these works would last a few minutes, others for days. By making the Egyptian Identity a mural, rather than a collection of smaller works or graffiti, artist-activists made it a point that collaboration is central to engaging with and resisting increased policing of public space. Even when the mural became frantic in 2015, the work was still collaborative, coordinated, and artist-activists depended on each other to make it happen. This is counter to the general feeling that the revolution has become segmented with diminishing amounts of trust that was central to bringing down the regime in the first eighteen days of the revolution.

Two days after the mural’s erasure on November 11, 2015, an artist-activist went back alone during the very early morning hours with three cans of spray: dark green, dark red, and hot pink. He sprayed a stencil that read: “This is Unacceptable” (Figure 8).24 The writing is accentuated with vowel marks to ensure it is read correctly in local Egyptian vernacular and is put in parenthesis similar to those found when quoting the Quran. The stencil is a direct response to a speech delivered by President El-Sisi just a day before where he scolded Egyptians and the media for saying that he does not care about them. In his speech, El-Sisi presented himself as the patriarch who is invested in the safety and security of his children, the Egyptian people. During the speech, El-Sisi said maysahish keda, “this is unacceptable,” over and over again when addressing media reports against him during floods in Alexandria.25 The artist-activist’s choice of location, on the freshly painted wall, not only mocks the president’s speech, but also signals that the erasure of the mural, and in turn the erasure of citizens’ participation in political and cultural change, is unacceptable.

Figure 8: Unknown artist, This is Unacceptable, November 2015, spray paint, 6.5 ft x 1.6 ft (2 m x 0.50 m). Qasr El-Nil Street, Cairo, Egypt. (Photograph: alma aamiry-khasawnih)

- Translation is my own from Arabic ↩

- Information differs on what the name of the mural is. In this paper, I will use Egyptian Identity mural because it offers less of a claim over the meaning of the mural, especially since I cannot find a direct quote from any of the artist-activists referencing the name of the mural. I used the title given to the mural in the edited volume Walls of Freedom: Street art of the Egyptian revolution because many of those who worked on the mural contributed to the publication. See Basma Hamdy and Don Stone, eds., Walls of Freedom (Berlin: From Here to Fame Publishingx, 2014), 247 and 249. ↩

- See Mona Abaza, “The Field of Graffiti and Street Art in Post-January 2011 Egypt,” in Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art, ed. Jeffery Ian Ross (New York: Routledge, 2015); Mona Abaza, “Walls, Segregating Downtown Cairo and the Mohammed Mahmud Street Graffiti,” Theory, Culture & Society 30, no. 1 (2013); Mona Abaza, “Intimidation and Resistance: Imagining Gender in Cairene Graffiti,” Jadaliyya, 30 June, 2013, http://www.jadaliyya.com/pages/index/12469/intimidation-and-resistance_imagining-gender-in-ca; Mona Abaza, “The Dramaturgy of A Street Corner,” Jadaliyya, 25 January, 2013, http://www.jadaliyya.com/pages/index/9724/the-dramaturgy-of-a-street-corner; Mona Abaza, “The Revolution’s Barometer,” Jadaliyya, 12 June, 2012, http://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/26220/The-Revolution%60s-Barometer. ↩

- See Soraya Morayef, Suzee in the City, accessed 24 February, 2018, https://suzeeinthecity.wordpress.com/. ↩

- See Georgiana Nicoarea, “The Contentious Rhetoric of the Cairene Walls: When Graffiti Meets Popular Poetry,” RomanoArabica 15 (2014); Georgiana Nicoarea, “Cairo’s New Colors: Rethinking Identity in the Graffiti of the Egyptian Revolution,” RomanoArabica, 14 (2014). ↩

- Basma Hamdy, “The Power of Destruction,” in Walls of Freedom: Street Art of the Egyptian Revolution, ed. Basma Hamdy and Don Stone (Berlin: From Here to Fame Publishing, 2014), 247 and 249. ↩

- Angela Boskovitch, “Qasr el-Nil Mural, a Dialogue of Form and Topic,” Sada: Middle East Analysis, September 30, 2013, http://carnegieendowment.org/sada/53144. ↩

- Abaza, “Walls, Segregating Downtown Cairo,” 130. ↩

- Nicoarea, “The Contentious Rhetoric of the Cairene Walls,” 110. ↩

- Joel Beinin, “The Working Class and the Popular Movement in Egypt,” in The Journey to Tahrir: Revolution, Protest, and Social Change in Egypt, ed. Jeannie Lynn Sowers and Christopher J. Toensing (London: Verso, 2012), 92. ↩

- Joel Gulhan, “Rights group condemns proposed graffiti law,” Daily News Egypt, 6 November, 2013, http://www.dailynewsegypt.com/2013/11/06/rights-group-condemns-proposed-graffiti-law/. ↩

- Gulhan, “Rights group condemns proposed graffiti law.” ↩

- Boskovitch, “Qasr el-Nil Mural.” ↩

- Translation is my own from Arabic. ↩

- Translation is my own from Arabic. ↩

- Boskovitch, “Qasr el-Nil Mural.” ↩

- Maspero is the State Television station building. During the first 18 days of the revolution, the news coming out of Maspero denied that anything was happening in downtown Cairo, then represented those in Tahrir Square as hooligans, infiltrators, and spies. It was also site of clashes that took place on 11 October 2011, when a number of Christian Copts were shot by live ammunition and run over by tanks during a peaceful demonstration against the burning of St. George Church a few days before. Therefore, this building represents the state, corrupt media, and state sanctioned violence. ↩

- At its most active, the Mona Lisa Brigades had close to 30 members of women and men from all over Cairo. They were formed in early 2011 and continue to exist today with a much smaller crew. ↩

- The police force in Cairo is run by the Ministry of Interior. Before and during the revolution, the police (and in turn the Ministry) were seen as perpetrators of violence against demonstrators. Their role was understood very differently than that of the the military, which was seen as a force protecting the demonstrators during the first 18 days of the revolution. The roles changed when the military (Supreme Council of the Armed Forces) took over state affairs on February 11, 2011. The police retreated and left the military to inflict violence on the Egyptian people. By 2013, the police were reentering the everyday scene again. ↩

- Translation is my own from Arabic. ↩

- The forehead mark is an indication of devotion that is made by putting a stone on the ground that hits the forehead every time one brings down their head to the ground as part of the Muslim prayer. This act bruises the forehead and repetitive bruising leaves a permanent mark. ↩

- El Zeft, “The Revolution Blender,” in Walls of Freedom: Street Art of the Egyptian Revolution, edited by Basma Hamdy and Don Stone (Berlin: From Here to Fame Publishing, 2014), 252. ↩

- Observation from own field notes; also see “Mohamed Mahmoud demolition for beauty, not politics, says Cairo official,” Mada Masr, 18 September, 2015, http://www.madamasr.com/news/mohamed-mahmoud-demolition-beauty-not-politics-says-cairo-official; Sally Toma, “Requiems and dreams: The struggle for Egypt’s memory,” Mada Masr, 16 December, 2014, http://www.madamasr.com/opinion/requiems-and-dreams-struggle-egypts-memory; Abaza, “Walls, Segregating Downtown Cairo”; Abaza, “The Dramaturgy of A Street Corner.” ↩

- Translation is my own from Arabic. ↩

- Motargam Videos, “El-Sisi Wrought-up Attacks the Media: This is unacceptable,” Youtube video, 2 November, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kPgt5Zlo6ww. ↩