Sky is a sea of darkness,

when there is no sun

Sky is a sea of darkness,

When there is no sun to light the way

When there is no sun to light the way

There is no day

There is no day

There’s only darkness

Eternal Sea of Darkness.

— Sun Ra

Puerto Rico, a US Territory with a population of 3.474 million people, that is neither a sovereign nation nor state of the union. The island is currently in the midst of an ongoing financial crisis with an accrued debt of over $73 billion and $49 billion in pension obligations, the largest economic insolvency in the history of the United States. The fiscal crisis has seen an abundance of meme trends that unveil the frustrations of the citizenry after decades of corruption, react to the recent imposition of a Fiscal Control Board, and draw on the island’s thorny history as a colony of the U.S.

Who else, but a godless Richard Dawkins to coin the term “meme”? The evolutionary biologist and author used the expression to denote an “idea, behavior or style that spreads from person to person within a culture” in his 1976 book on evolution, The Selfish Gene, Dawkins categorized “replicators” when referring to copied coded information contained in genes, as a dynamic system that yields the production of a copy of itself.1 Relatedly, an internet meme, can be described as an “activity, concept, catchphrase or piece of media which spreads, often as mimicry, for comedic purposes, (…) via the internet.”2 Internet memes manifest themselves as images, text and/or video that spread through sharing and appropriating. As a consequence, the seriality and virality of internet memes can be seen as conduits for the transmission of a specific culture, and meme creators as transcribers, counterfeiting images for gut-busting networked correspondence.

In conceptual and semantic terms, internet memes share an association to the French adjective même, which means “same”; a recurring trope that denotes matching, akin, or collectively experienced situations. The formatting of memes often follows a repetitive structure that invites affinity, captured by examples such as “that feeling when (TFW),” “I know that feel, Bro”, or “My Face When (MFW).” It is to no one’s surprise that this meme format mutated and was subsequently transcoded into the Spanish; “Mi cara cuando…” and so on. In this same manner, a multitude of memes that originated in English have been rendered and adapted into Spanish and/or Spanglish, accommodating the myriad realities coded into that language and dialect.

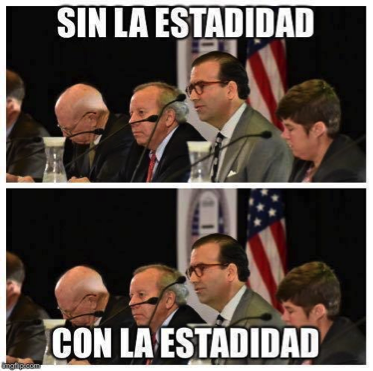

A fresh batch of memes were devised in light of Puerto Rico’s 2017 referendum fiasco, in which the governing political party, favoring statehood, concocted a rigged plebiscite that was boycotted by all other political parties and ended up costing $7.2 million to the already cash-strapped archipelago.3 Referendum memes collated a dissimilar pie-in-the-sky conception of what Puerto Rico would become as a state, contrasted to the island without statehood, playing with the assumed, illogical, fear of dispossession of statehood supporters. One recurring trope within the meme parlance, recurrent in its manifestations, is the juxtaposition of two dissimilar images linked together by framing, but disjointed by their pure binary opposition. In Figure 1, we can spot in the image, the futileness of a non-binding referendum, where ultimately, U.S. Congress and the Congress appointed Fiscal Control Board are the de-facto government. Figure 2 sardonically re-imagines Puerto Rico, a tropical weather island in the Caribbean, as a winter wonderland were statehood granted after the plebiscite.

Figure 1 On top: without statehood. On Bottom: with statehood.

Plus ça change, plus c’est la meme chose

Aria Dean, the assistant curator of Net Art for the journal Rhizome, wrote in her pivotal essay “Poor Meme, Rich Meme” that “relatability helps memes sustain a kind of cohesion in ‘collective being’, a collective memory that can never be fully encompassed; one can never zoom out enough to see it in its entirety.”4 Never being able to zoom out of a perceived reality is a lot like living in an island in the Caribbean. Etymologically, the word island traces back to isolation; surrounded by water, detached from a mass. One can effortlessly envision arbitrary images of marooned castaways abandoned on islands as punishment. If you zoom out of an island, there is nothing, thus, attention moves inward.

Dean also harkens back to Laur M. Jackson, author of “The Blackness of Meme Movement,”5 when she points out that memes, specifically those originating from black online communities, “are also black in their survival tactics, (…) the ways they mutate and twist and split and circle back on themselves embody the already established trends of black cultural production and circulation.”6 Jackson stresses the importance of black meme creators, a notion often erased in the manic consumption, re-appropriating and discarding of online culture. Both Dean and Jackson also accentuate the role and appropriation of black vernacular in meme culture, pointing out that its “diction, (…) style, and politics” are ascribed to a specific community and linguistic context.7 Pronunciation, phrasing and delivery are integral cues in Puerto Rico’s crisis memes. The depicted vernacular language signals to an unequivocal locality. Membership is affirmed by understanding of inside jokes, ascribing to viewpoints expressed, and detection of dialectical cues.

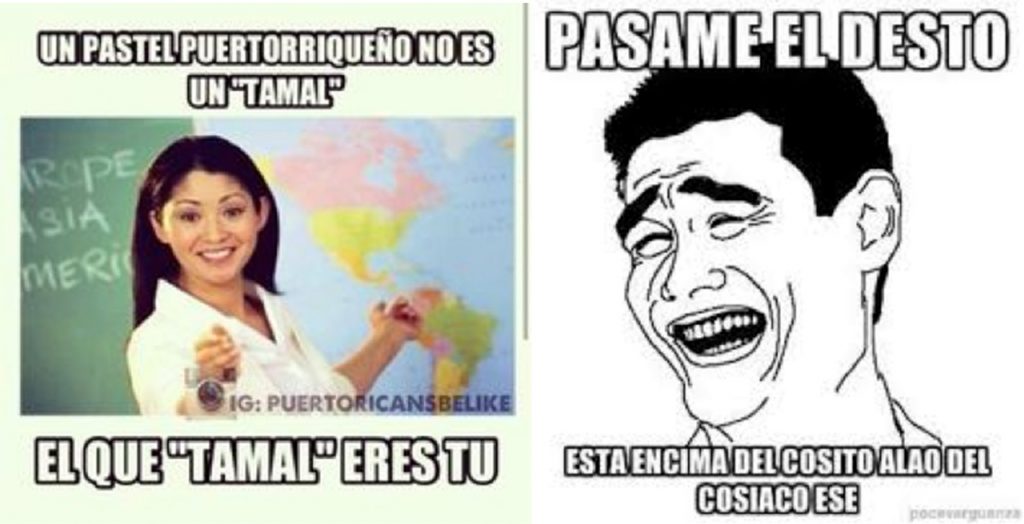

Figures 3 and 4 Examples of memes that play upon the pronunciation of Spanish, and discourse fillers used by Spanish speakers in the Caribbean

Due to its location, demographics, and history, the Spanish spoken in the Caribbean is oftentimes inflected with a particular cadence. For example, consonantal weakening is common throughout the Spanish speaking Caribbean, where an aspirated word final /-s/ ends up sounding like an [h].8 An Afro-Caribbean imprint in language, in addition to borrowed speech and pronunciation from creole and patois from neighboring islands has marked the syntax and diction of Spanish speakers in the Caribbean. Typically, the Spanish spoken in the Caribbean also favors expediency and succinctness. A running joke within the Latin American community is that people hailing from the Caribbean speak “bad” Spanish, that is difficult to understand as a result of its pronunciation and incantation.

Spanglish, a term coined by Puerto Rican poet Salvador Tió in the late 1940’s, is a dialect that results from cannibalizing the English and Spanish languages. The emergence of Spanglish as a result of the imposition of the English language when the U.S. occupied the island reveal a simultaneous assimilation and resistance to “American” culture. As a widely used cultural symbol it purposely marks and delineates Puerto Rican vernacular as “other” while maintaining ethnic autonomy.

Puerto Rican memes are repurposed from U.S.-centric formatting and thus acquire an idiosyncratic quality that is dispatched to its intended audience through the use of colloquialisms, while also commenting on a topical set of circumstances that affect people living in the island and the diaspora. Furthermore, Puerto Rican memes crack at and offer judging appraisals on a broad range of issues, ranging from mindless “beefs” between irrelevant reggaetón artists to the contradictory, ahistorical notion of a colony wanting to belong to and become incorporated into a culturally, geographically distant imperial power. They also offer commentary on media discourses, such as the local media’s depiction of student activists as long-haired felons, communists and marihuana smoking dope-fiends, and offer many other topical encapsulated nuggets of popular wisdom.

In recent years, linguists have been able to use social media data to research the proliferation of new words and terms through social media. For instance, in 2014 scholar Lauren Squires investigated and tracked the transmission of the term “lady pond” from its origins—it was first uttered by a reality television personality on Bravo TV—to its use and spread on social media and beyond. Their conclusions suggest that Twitter, and social media at large is a “significant site of colloquial linguistic exchange” which lends itself to the investigation and circulation of language.9

Puerto Rican meme production has materialized into a media practice that encapsulates and contests the disenfranchisement of its young citizens, where one of the austerity measures proposed by the Fiscal Control Board is to lower the minimum wage to $4.25 for citizens under 25 years of age. When memes catch on they become unstoppable and difficult to control, both for cultural heritage institutions and the state. Because memes have the power to “crystallize whole schools of thought,” they become a force to be reckoned with which can’t be contained. They resist categorization, and oppose decorum.10

Seizing The Memes of Reproduction: The Puerto Rican Economic Crisis (Briefly)

The origins of Puerto Rico’s $73 billion government debt are inexorably entwined with its political status as an unincorporated territory of the United States. Puerto Rico is neither a state of the union nor a self-governing nation. The island has been a possession of the U.S. since the 1898 Treaty of Paris, an agreement with Spain that ended the Spanish-American War and forced the imperial power to relinquish its still-standing colonies (Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines) to the United States. After a few decades, during which Puerto Rico was ruled by a military government and had its officials appointed by the President of the United States, Congress passed the Jones-Shafroth Act in 1917, which granted Puerto Ricans U.S. Citizenship. In 1947 Puerto Ricans were granted the right to democratically elect their own governor (thank you!), and in 1950 Congress allowed for Puerto Rico to write its own constitution (benevolent!) which, after congressional approval, went into effect in 1952 (#blessed!). Journalist Juan González provides some context:

For decades, Puerto Rico was important to the American economy as a center of sugar cane growing, then as a tax haven for manufacturing and pharmaceutical companies, and as a military stronghold and bulwark against the spread of communism in Latin America. But now it is no longer needed for any of these things. Most of the U.S. military bases have closed, and Congress began in 1996 to phase out the island’s tax haven status. As soon as the last of the federal tax breaks — known as Section 936 — ended in 2006, corporations started leaving and the island plunged into a recession from which it has yet to recover. For the past 20 years, a succession of island governments has been closing structural operating deficits with borrowed funds supplied by Wall Street firms eager to market its triple tax-exempt bonds to wealthy and middle-class Americans and Puerto Ricans.11

Because the U.S. profits off its relationship with Puerto Rico, the nation’s interconnection is decidedly unequal and sadistically maintained by U.S. Congress. For example, since 1976 the federal government has been granting U.S. corporations a tax exemption to income originating from US territories under the section 936 of the tax code. In addition, Puerto Rico’s corporate tax system provides significant incentives for U.S. corporations to set up subsidiaries, mainly petrochemical and pharma companies, on the island. Income generated by these subsidiaries is not subject to U.S. income tax, and only 12% of the entire workforce in Puerto Rico at the time was employed by companies benefiting from section 936.12 The expiration of section 936 in 2005 has been a major contributor of the island’s economic depression. Its elimination was promoted by New Progressive Party Governor Pedro Rosselló whose son Ricardo Rosselló is the current governor of Puerto Rico.13 Today, $35 billion in manufacturing profits made in Puerto Rico (a third of the island’s Gross National Product) is returned back to the United States and not reinvested in the island. Heriberto Martínez-Otero and Ian Seda-Irizarry, expand on other contributing factors to the crisis;

Factors such as the popping of a construction bubble, the dismantlement of the industrial model of development, the expiration of a federal tax break for corporate income, the approval of CAFTA-DR,14 changes in the global economy, incompetent and servile government administrations, and the island’s colonial relationship with the United States have all contributed to an economic depression that predated the [2008] worldwide crisis.15

In 2009 New Progressive Party conservative Luis Fortuño was elected governor, and as consequence, public policy took a sharp neo-liberal turn which included the discharge of 30,000 public sector employees, increases in tuition for higher public education, the privatization of Puerto Rico’s airport, contracting out the construction of a gas pipeline to a childhood friend, and the loosening of environmental protection laws to lure in foreign investors. All the while, Fortuño’s government managed to rack up $16.55 billion in debt and confer contracts for undisclosed professional services totaling to $9,000 million.

To restore fiscal responsibility and in keeping with its quasi-colonial status, Congress signed into law the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA) in 2016.16 PROMESA granted an unelected seven member board, referred to as the Fiscal Control Board, constitutional power over Puerto Rico’s government. The fiscal control board’s powers concerning the future of Puerto Rico include the following:

The board may issue subpoenas, certify voluntary agreements between creditors and debtors, seek judicial enforcement of its authority, impose penalties, and enforce territorial laws prohibiting public sector employees from participating in strikes or lockouts. The board’s responsibilities include:

● approving the governor’s fiscal plan;

● approving annual budgets;

● enforcing budgets and ordering any necessary spending reductions; and

● reviewing laws, contracts, rules, and regulations for compliance with the fiscal plan.17

In addition, the fiscal oversight board has the “authority to force the sale of government assets and establish efficiencies that consolidate agencies and reduce workforce.”18 It is no coincidence that members of the board include former Santander bank executive and president of the BGF (Puerto Rico’s Government Development Bank, and government bond issuer) Carlos Garcia and José Carrión III, who is a shareholder of Banco Popular, the island’s largest bank, which is also amongst the list of creditors. According to reports Santander participated in underwriting $61 billion in Puerto Rican bonds, in which $1.1 billion were paid to Santander and others in issuance fees.19 The U.S. Republican party’s House of Representatives Speaker Paul Ryan and Senate Majority leader, Mitch McConnell chose members of the oversight board, while Carrión has donated at least $80,000 to US political candidates including Jeb Bush and Marco Rubio.20

Colonization assumes the supremacy of one culture over another, while demanding the colonized subject to define “who they are as people.” Puerto Rico’s artistic output has frequently grappled with defining what it means to be Puerto Rican, almost to the point of mania, with almost no other theme or motif extant. Of course, Frantz Fanon, and others have written at length about the psychological and psychiatric effects of colonialism on its subjects. The effects of colonialism on the colonized is reminiscent of the consequences of emotional abuse on humans. The trauma of centuries worth of colonialism is repressed and blocked, and colonized subjects may suffer from dissociative amnesia in an effort to erase a disturbed, violent past. The internal state of consciousness can only find its way out through carnivalesque outpouring.

The Wretched of the Screen: Rican Specific Meme Societies, Collectives and Artists

An old adage goes that politics, not baseball, is the national sport of Puerto Rico. The current fiscal crisis and the island’s longstanding colonial status have served as a wellspring of idiosyncratic, sardonic and probing memes that cut deep into the outrage of Puerto Rico’s population and into the crassness of the ruling government’s austerity measures. This is what scholar Manuel Avilés Santiago calls the patria digital or in English, the “digital motherland” which steps in as harborage in the absence of a legally recognized “motherland.”21

In her essay “In Defense of the Poor Image”, visual artist Hito Steyerl describes how the poor image—low-quality copies in motion—constructs “anonymous global networks just as it creates a shared history,” adding that the poor image “builds alliances as it travels, provokes translation or mistranslation, and creates new publics and debates.”22 Such images emerge and circulate in a variety of contexts, ranging from the ostensible echo-chamber of “Film twitter” a loose amalgamation of film nerds regurgitating hot takes on film, to the alt-right online community and its meme production. Steyerl continues:

The networks in which poor images circulate thus constitute both a platform for a fragile new common interest and a battleground for commercial and national agendas. They contain experimental and artistic material, but also incredible amounts of porn and paranoia. While the territory of poor images allows access to excluded imagery, it is also permeated by the most advanced commodification techniques. While it enables the users’ active participation in the creation and distribution of content, it also drafts them into production. Users become the editors, critics, translators, and (co-)authors of poor images.23

Remixed, shared and spun into hot-takes, memes have entered the idiosyncratic lexicon in Puerto Rico. So much so, that you often encounter mainstream media commenting on its rapaciousness, in a pitiful attempt to re-establish its relevance. Family owned media, distribution, marketing and real-estate empire GFR (Grupo Ferré Rangel) Media runs three local daily newspapers and dominates political discourse with its influence and power. El Nuevo Día, the publication with the largest circulation in the island, was bought by Luis Alberto Ferré Aguayo, former governor and founder of the pro-statehood party Partido Nuevo Progresista, and is currently directed by his son, Luis Alberto Ferré Rangel. Another popular tabloid newspaper, Primera Hora, was founded by another heir of Ferré, Antonio Ferré, and its current editor in chief is his daughter, Maria Luisa Ferré-Rangel. El Nuevo Día is a member of the Inter American Press Association (IAPA), an organization that has been frequently accused of right-wing bias, and which represents owners of large media corporations in Latin America, with close ties to the CIA.

Memes provide citizens with an empowering way to express themselves outside of traditional media circuits, something that had not existed before. Memes embody how you interact with friends and family from the diaspora, and you wouldn’t put it past yourself to utilize memes as a vehicle for flirting with someone. Sharing the source of your favorite deep-cut memes means something. But, Puerto Rican memes go beyond their quality as a sort of folk expression contained and experienced on the web. As a preconditioned sociolinguistic phenomenon, they may also operate as a ceremonial purge of the effects of colonialism; a twenty-first century take on cybernetic syncretism. An amalgamation of cultures and firmly held opinions uploaded, compressed and ripped into contempt and defiance. They are wretched in their conveyed delivery, but not in their manufacturing.

In the following sections, I will revise and describe popular meme pages that explicitly address the leading up and current status of Puerto Rico’s fiscal crisis. A number of the Facebook meme pages explored in this essay are administered by various individuals, many of which overlap and oversee various meme groups. Inter-meme-page quarrels are not uncommon and almost all of the meme pages employ a participatory mode of production and incite interactions by their online audiences.

PuertoChan

Appearing on the internet in 2010, PuertoChan is Puerto Rico’s response to 4chan, the popular English language imageboard website and probably the first collated website to broadly feature Puerto Rican memes. Puerto Chan’s logo, which has mutated over the years, is a vector image rendering of the flag for the 1868 Lares Uprising, remixed and referenced extensively on the forum.24 PuertoChan was notorious for its /r/ recreo channel, a free-form random channel where an overabundance of memes came into sight and became hugely popular. It was known for its disorderly and rowdy anonymous users, who fiercely defended free-speech and created top-notch memes that swiftly spread through other online communities, especially amongst young people. This was probably where Puerto Rican meme culture started. After several hacks and for allegedly “mysterious” reasons, the image board ceased operations in June 2016. We laughed, we cried, se pasó cabrón.

Memes en la Trienal Poli/Gráfica de San Juan

An early attempt from the art world to capitalize upon the singularity and popularity of the Puerto Rican meme culture was the incorporation of an online exhibit, titled #elmemestaenlatrienal or “triennial memes” into the 4th Poly/Graphic Triennial of San Juan, an international arts and cultural event sponsored by the Government of Puerto Rico and the Institute of Puerto Rican Culture. The 4th edition of the triennial, celebrated in 2016, was curated by Gerardo Mosquera, Vanessa Hernández-Gracia, and Alexia Tala. The theme of the triennial aimed to “examine the formal and conceptual displacements of the graphic image between different fields, media, backgrounds, (and) senses.”25As part of the triennial activities, an open call was made to the general public to create memes and post them on various social media, accompanied by the hashtag #elmemestaenlatrienal.26 The open call sought to “make the processes of recycling and displacement of images visible, without actively enforcing them.”27

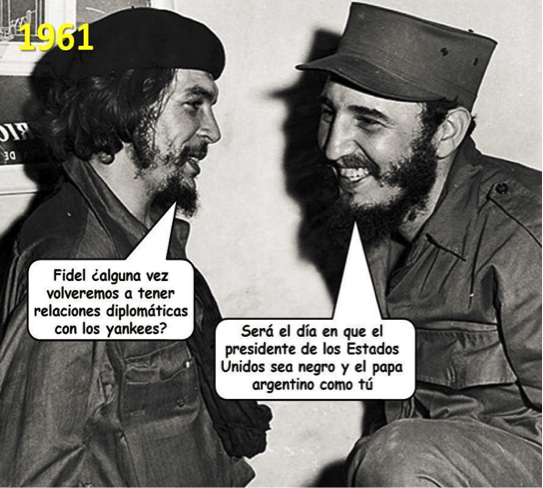

Figure 5 Ernesto “Che” Guevara: “Fidel, will we ever have diplomatic relations with the Yankees? Fidel Castro: “On the day that the president of the United States is a black man and the Pope an Argentine like you. [Author note: this meme example was only funny from 2015-2016.]

Aimbot

In internet culture, an Aimbot is a type of computer game bot that will auto-aim and shoot an enemy for a player in first-person shooter games. Their use in online gaming is considered as cheating by most players. The aimbot meme persona, on the other hand, creates the kind of layered, satirical video art that Puerto Rico has been thirsting/yearning for decades. Self-described as an independent production house based out of San Juan, Puerto Rico, this visual arts Facebook page is much more than that. With approximately 5,500 followers, aimbot samples and manipulates the visual aesthetic of national television stations, gaming platforms, movies of yesteryear with references to fragmented pieces of pop culture, and all other memes under the sun. aimbot’s visual prowess and humor is striking in for example, a June 6, 2017 video post titled: BBC Documentary of the Search for Douglas Rolón at the ancient ruins of the University of Puerto Rico Rio Piedras Campus. The video, riffs on the BBC’s officiousness, the documentary style of Werner Herzog, Ruggero Deodato’s Cannibal Holocaust, and the internal politics of the University of Puerto Rico—the largest public university—during the 2017 student’s strike, which lasted 69 days, in under 5 minutes.

Figure 6 “BBC Documentary of the Search for Douglas Rolón at the ancient ruins of the University of Puerto Rico Rio Piedras Campus,” video by aimbot

¡Batata!

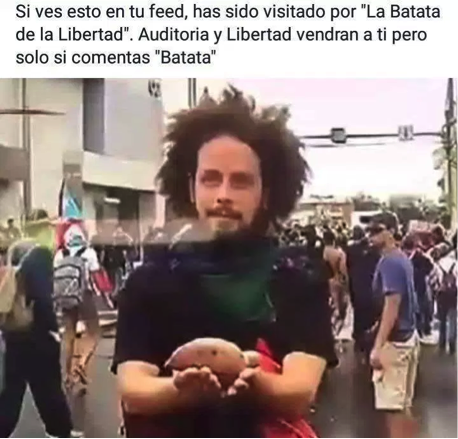

During the May 1st, 2017 National Strike, a young man holding a sweet potato, bombed Telemundo’s live broadcast and blurted out: ¡Batata! (“Sweet Potato!”) in deadpan, hilarious fashion. For those uninitiated in the wonderful world of Puerto Rican slang, a batata, is a term used for a member of the incompetent, corrupt political class that can easily parlay into government and be essentially bought at asking price. A sweet potato is an unsightly, starchy, tuberous root with low nutritional value. In an exclusive interview, conducted by alternative digital magazine, La Marginal, batata boy waxes poetic on the attributes of fresh Puerto Rican memes, this being one of the few video-centric ones in the repertoire:

Ultimately, I think the thing that surprised me the most was the proliferation of using memes as a means for politicization, in both irreverent and radical ways. (…) I am not saying what I did was something extremely radical. Not at all. But, people were tickled in a spot that had not been titillated in a while.29

He also concluded that “the political class doesn’t do anything for me, so we should eventually transcend these batata people. Because, it’s giving batatas a bad name.”30

Figure 8 “If you see this on your feed, you have been visited by the Freedom Batata. An audit of the debt and freedom will be yours only if you comment ‘Batata'”

Frente Amplio para la Re-Celebración de la Gran Regata Colón ‘92

This 650 member Facebook group is a self-described historiographical, memetic and feminist project. It appears to be supervised by many individuals that create memes around “Spanish colonization of the Americas and other imperial powers, pre-Raphaelite art, maritime themes before metal vessels, regatta boat shows, and topics relating to pre-Hispanic cultures.”31 The page’s name mocks the 1992 Colón Regatta, a spectacle of an event that consisted in 200 tall ships setting sail from Cádiz, Spain docking in San Juan, Puerto Rico as a commemoration of Christopher Columbus arrival to the Americas. In their page description, the group also adds a disclaimer asking users not to post memes originating from a page ran by adversary radio personality, comedian, and low-brow meme regurtitator, Molusco. At the time of writing 907,760 Facebook users follow Molusco’s page.

Frente Memero de Liberación Nacional

Taking cue from the FALN (Fuerzas Armadas de Liberación Nacional/Armed Forces for National Liberation), a militant marxist-leninist group that championed Puerto Rican independence and was active throughout the 1960’s-1980’s, the Frente Memero de Liberación Nacional is a 5-star rated, Facebook “political party” group that elucidates that they seek the “liberation for Puerto Rico and all of its lands, independence ‘till death, hopefully we’ll get it before it comes to that.”32 Though not as active as the other pages listed, FMLN is noted for photoshopping the sad faces of local politicians and senators onto tuberous roots.

Figure 11 Starchy Secretary of Justice, Wanda Vázquez, President of the Senate, Thomas Rivera-Schatz and disgraced former mayor of Guaynabo, Héctor O’Neill tubers.

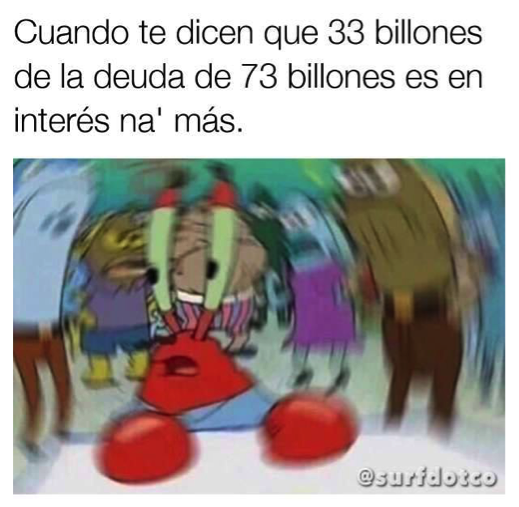

Figure 12 “When they tell you that $33 billion out of a debt of $73 billion is merely the rate of interest.”

Isla de Cabra Cinematic Society

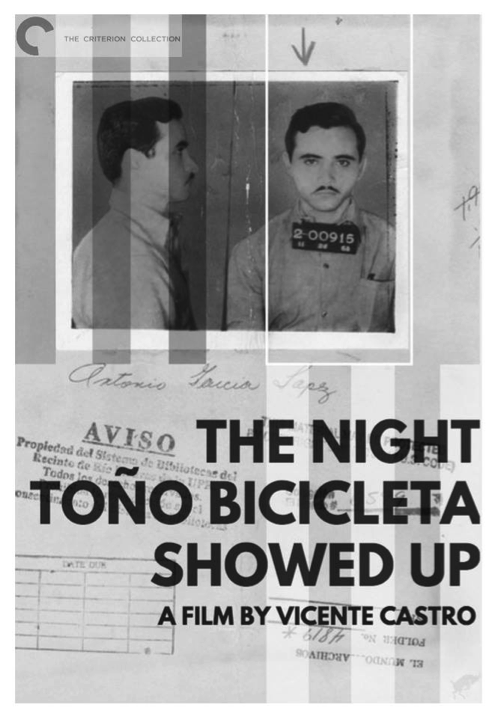

Originating in January 2017, Isla de Cabra Cinematic Society is a public Facebook group with approximately 300 members devoted to disseminating memes that draw upon the days of yore of Puerto Rican national television networks (that have since privatized or have been bought off by larger multinational networks) and the slim, albeit rich Puerto Rican cinematic tradition. Isla de Cabras (which translates as Island of Goats) is a small islet located near the bay of San Juan that, to the amusement of many nowadays, was used as a leper colony during the Spanish colonial period. ICCS is as per its mission statement the “Foremost and Most Recognized Goatislander Organization for the diffusion and discussion of the Seventh Art.”33 In the meme sample below, film connoisseurs envision the Criterion Collection release of the 1997, made for T.V. movie The Night Toño Bicicleta Showed Up by trash auteur Vicente Castro. According to one of the page’s creators it was started as a joke inspired by the Fake Criterions Tumblr, and a sincere preoccupation with certain lowbrow elements of Puerto Rican culture not being examined and discussed.

Figure 13 Criterion’s Special Collector’s Blu-ray of Vicente Castro’s “The Night Toño Bicicleta Showed Up”

MemeFrito

MemeFrito’s administrators are formally trained artists, therefore their meme output intentionally closes in on fine art collage. Juxtaposing disparate images of software navigation windows, Rican product placement, and substantial doses of symmetric repetition, featuring Osama Bin Laden, Christopher Columbus, and Teletubbies in the company of our most colorful politicians. In the example below, the meme criticizes Goya Foods decision to pull out its sponsorship of New York City’s Puerto Rican Day parade following the parade’s organizing committee decision to honor Oscar López Rivera, a Puerto Rican independence activist that had been imprisoned for 35 years and subsequently pardoned by President Barack Obama, in 2017.34 Goya foods, which has the Latino food market cornered, has come under fire in the past due to their ultra right-wing bias, sponsoring the parade for 60 years until they decided to undermine the parade and the federal government’s decision to commute López Rivera’s sentence. The meme on figure 13 reads “thanks for nothing” and features iconography from Taíno culture,35 Christopher Columbus (the Columbusing O.G.), the New Progressive Party (PNP), and the Popular Democratic Party (PPDI have it on good authority that if you look up Goya’s boycott of the Puerto Rican Day Parade on the internet, it leads to the definition of being “butt-hurt.”

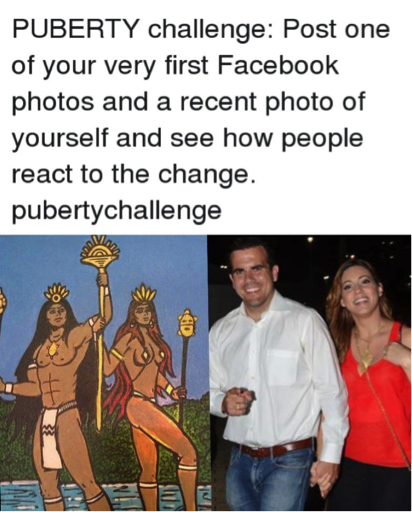

Figure 15 Governor Ricardo Rosselló and First Lady Beatriz Rosselló’s embarrassing puberty challenge pics as Spanish Gods. Playing on the trope that the indigenous peoples of America mistook Spanish colonizers as Gods.

Radical Cowry

Radical Cowry is popular Facebook page that frequently takes jabs at the class politics of Puerto Rico, endlessly mocking career politicians and residents of affluent suburbs. Like Isla de Cabra Cinematic Society, RC yields its inspiration from local children’s television shows from the 1980’s and 1990’s, like Chícola y La Ganga and Telecómicas. The page is currently being followed by 49,777 users, and is reportedly, is the source of many of Molusco’s reposts.

Referendum Memes Tumblr

This Tumblr page was created in the midst of the 2017 status referendum, which was boycotted by all main opposition political parties with the exception of the New Progressive Party, which is in favor of statehood. The referendum amassed a mere 23 percent of voter participation, in contrast to the average of 80 percent, and cost taxpayers $7.2 million in the middle of an economic crisis. The page captures about 80 memes, and was open to submissions in the weeks following the plebiscite.

Figure 18 Rosselló’s statehood granting gamma rays can make you experience austerity induced hunger in English!

Archiving the Meme: Let Me Show You My JPEG Collection

Most, if not all, of Puerto Rico’s meme output is contained on social media, on platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. Archives in Puerto Rico are not actively collecting digital culture, online communities, or image macros, like, for example, the American Folklife Center is.36 As archivists love to expound, none of these social media platforms should be treated as an “archive” or repository for one’s digital content, in the sense that these corporations do not provide ongoing maintenance of the digital files uploaded to them, a basic tenet of digital preservation.37 They also lack a mission statement to preserve and provide access to the content captured in these networking websites. As time progresses and widespread use continues, an individual’s social data may fall from their helm. Furthermore, as social data is now stored on third-party servers, individuals will see themselves less and less in control of the digital content they’ve produced and will depend on those very platforms to retrieve their information. When I asked meme producer aimbot, their thoughts and opinions about archiving memes, I received this response:

Creo que archivar m0m0s es un ejercicio redundante, los m1m1s ya existen en el INTERNET, eso es suficiente. No me gustaría ver una base de datos centralizada de mims, mucho menos ver uno enmarcado. Veo cualquier esfuerzo de “legitimar” a los m3m3s como arte como un fallo en ver que los m5m5s son otra cosa en su propia categoría.

I think archiving m0m0s is a redundant exercise, m1m1s already exist on the internet, that is sufficient. I would not like to see a centralized mim database, nor a framed one. I see any effort to legitimize m3m3s as art like a failure to see m5m5s as a category of its own.

Redundant as it may seem, it is a reality that links rot (about a quarter of them every 7 years), bits flip, servers may go offline and images may disappear from the web. Over 75 percent of all websites are inactive, while economic shifts, social unrest, and online fads can also contribute to the wiping out of entire online ecosystems. Redundancy is the basic principle of LOCKSS (Lots of Copies Keep Stuff Safe), a library led program that started in 1999 at Stanford University Libraries “in order to support the library community in a increasingly digital age with an inexpensive, technologically robust way to safeguard and control its digital assets.”38

Recent events such as the Trump administration’s scrubbing of environmental data from EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) website corroborate that just because an object existed on the internet does not mean that it will remain there.39 Major cultural heritage institutions such as the Internet Archive (IA), the Library of Congress (LOC), and the California Digital Library (CDL) have been tackling the matter of website archiving— the capture and preservation of completely rendered websites and the sustainability of digital formats. In 2010, the Library of Congress announced that it would collect and archive tweets from Twitter. In the span of 3 years, the LOC had collected 170 billion tweets. Since then LOC has concentrated its efforts on working around the challenges of providing access to researchers considering the massive size of the data collected. In a white paper update on the progress of the assembling of the unprecedented collection, LOC defined the value of Twitter and the merit in archiving social interactions contained in social media;

As society turns to social media as a primary method of communication and creative expression, social media is supplementing and in some cases supplanting letters, journals, serial publications and other sources routinely collected by research libraries. Archiving and preserving outlets such as Twitter will enable future researchers access to a fuller picture of today’s cultural norms, dialogue, trends and events to inform scholarship, the legislative process, new works of authorship, education and other purposes.40

In 2010, Facebook started offering a service that allowed users to download data from their personal profiles, including photos, posts, messages, event information, friend requests, and chat conversations. The files are downloaded as a .zip file, and data is segregated into folders according to their file type. However, Facebook does not offer this service to groups or business pages with multiple administrators, and does not include the option to omit data from their download. While you are able to download your personal data for your own digital archiving purposes, you are not allowed to do so for collective managed pages, leaving those records up for elimination. Twitter introduced its “archiving” service in 2012, allowing downloads in .HTML format that can be navigated by month. A user is able to search their archive by keywords or hashtags, but after downloading their data for the first time, a user must wait an approximate of two weeks to download their data a second time.

Of added concern is the fact that both Facebook and Instagram add compression to uploaded video and images, this involves encoding information using fewer bits than its original representation. An estimated 350 million photos are uploaded to Facebook every day, 70 million to Instagram.41 Because of the sheer amount of uploaded photos, both social media platforms apply compression to the images to “lighten the load.” Compression algorithms can be either lossy or lossless, lossy ones providing a loss of information from the source that is deemed “acceptable.” The majority of video compression algorithms use lossy compression and codecs, which combine spatial image compression and temporal motion compensation. Highly compressed video has a propensity for exhibiting visible distortions and artifacting. Currently, users don’t have the option to turn compression on/off. Facebook also restricts the video formats that may be uploaded to their platform as MP4 and MOV files to ones shorter than 120 minutes and under 4GB in size.

In 2014, North Carolina State University Libraries were awarded an EZ Innovation Grant (made possible by funds from the Institute of Museum and Library Services) to develop a toolkit to guide cultural heritage organizations towards collecting social media content.42 Comforting as it may be to rely on having an “archive” option on social media platforms, according to Cathy Marshall, principal researcher at Microsoft’s Research Silicon Valley Lab, no one is really backing-up their content, but instead, ironically, hoping that “someone else is doing the backup.”43

Another threat to digital cultural artifacts is the current of underfunding cultural heritage institutions. Of this, digital archivist Trevor Owens opines that: “To this end, one of the biggest things we can do to support digital preservation is to work toward demonstrating the value and relevance of our work to the communities we serve.”44 Puerto Rico maintains a National Archive, and various affiliated municipal and university archives, but none of them have a full-fledged digital preservation program, nor do they actively collect social interactions on the internet, or websites created on the island. In 2011, Puerto Rico’s Chief Information Officer, released a guide for document digitization aimed at piloting a large-scale document digitization project for government agencies, municipalities and corporations under the jurisdiction of the Program for Public Documents Administration of the executive branch of the Puerto Rican government.45 However, that document is only concerned with the scanning of paper-based documents and does not even consider born-digital objects.

In similar fashion, Puerto Rico’s General Archive, created in 1955, is in a collaborative project with the National Digital Archive of Puerto Rico (ADNPR), a recent private initiative that seeks to establish a strategic plan for digitizing documents, maps, periodicals, video, and audio, and make them available to researchers. The project came about in response to the General Archive lacking an index, inventory, and catalog in digital form, and is managed by volunteers. The University of Puerto Rico’s Rio Piedras and Mayagüez campuses also have ongoing projects that address the urgency of preserving and providing access to digitized or born-digital data, but the higher education institution has yet to recognize the significance of online culture and does not collect memes. In the Mayagüez campus, known for its top-notch engineering and agricultural science schools, has recently implemented a digital institutional repository (DiRe) that aspires to be a “central, digital data storage site for the scientific and creative work of the university.”46 While the Rio Piedras campus, the largest one in the public University system, is also developing its institutional repository which is yet to be made public, it will also compile/include recent digitization initiatives from its Puerto Rican Collection and will have an open access mission statement.

Transitioning from digitizing paper catalogs to archiving memes is a long stretch that is further complicated by up-to-the-minute information that, after contentions with the fiscal control board, the government passed its 2018 fiscal year budget, slashing the Institute of Culture’s (which oversees the General Archive) budget to $8,474,000 or about $57,000 less than the past fiscal year.47 For reference, the Georgia Archives was threatened to close its facilities in 2012 after a 3% budget cut equating to $732,626, and was forced to reduce its staff to three. By the same token, citizens may view memes as trivial JPEGs that circulate the web, but upon further inspection, memes help illustrate the cacophony of voices surrounding a pivotal moment in Puerto Rico’s history.

Post-script

Clifford Geertz’s appreciation of culture as a “vernacular web” delineates that, long before the internet, human beings were caught in “webs of signification” of their own doing/making. What we say, do, and create emerges out of a net of interaction that both predates and postdates us. At the dawn of the digital revolution, distinctions between folk and mass media were blurred in online discourse. Since then, we have become accustomed to consuming in-jokes, folk beliefs, rumors, and storytelling that are the products of a particular culture and chronicle the everyday. It is, of course, no different under the auspices of crushing austerity measures with little democratic power. In conversation, Rubén Ramos Colón, a contributing member of ICCS indicated that, “everything local is conjectured as a counterpoint to the opinions and regimen of an outside visual culture; but I think there is a style and intelligence and a calculated geometry in what is posed here, resources and opportunities that, I swear, are and will be fundamental when we are proposed new ways of seeing and recreating ourselves.”48 Post-Hurricane Maria and the devastating effects it had on the Caribbean, including Puerto Rico, it is challenging to conceive or re-image a collective future that protects itself from vulture hedge-funds and a criminally neglectful White House while simultaneously attending to basic needs like access to clean drinking water, electricity, nutritious whole foods, gainful employment, among other immediate needs. The most impacted areas in the island are outside of the major metropolitan areas and were memes to have any tangible power in moments of distress is by enabling community networks on isolated regions.

Pioneering Net artist and theorist Olia Lialina chronicled the first few years of user adoption of the world wide web and offers some encouraging thoughts on the possibilities of the internet and memes, especially when considering nations in crisis: “There was a pre-existing environment; a structural, visual and acoustic culture you could play around with, a culture you could break. There was a world of options and one of the options was to be different.”49 If a different world is possible, let memes guide the way.

- Olivia Solon, “Richard Dawkins on the internet’s hijacking of the word ‘meme,’” Wired, June 20, 2013, http://www.wired.co.uk/article/richard-dawkins-memes. ↩

- “Internet meme,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Internet_meme&oldid=798319529 (accessed June, 2017). ↩

- Van Newkirk II, “Puerto Rico’s Plebiscite to Nowhere,” The Atlantic, June 13, 2017, https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2017/06/puerto-rico-statehood-plebiscite-congress/530136/. ↩

- Aria Dean, “Poor Meme, Rich Meme,” Real Life, July 25, 2016, http://reallifemag.com/poor-meme-rich-meme/. ↩

- Laur Jackson, “The Blackness of Meme Movement,” Model View Culture, March 28, 2016, https://modelviewculture.com/pieces/the-blackness-of-meme-movement. ↩

- Dean, “Poor Meme, Rich Meme.” ↩

- Jackson, “The Blackness of Meme Movement.” ↩

- Ian Mackenzie, “The Linguistics of Spanish. Caribbean Spanish,” https://www.staff.ncl.ac.uk/i.e.mackenzie/caribbean.htm (accessed June 2017). ↩

- Lauren Squires, “From TV Personality to Fans and Beyond: Indexical Bleaching and the Diffusion of a Media Innovation,” Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 24(2014): 42–62, doi:10.1111/jola.12036. ↩

- Mike Godwin, “Meme, Counter-meme,” Wired, October 1, 1994, https://www.wired.com/1994/10/godwin-if-2/. ↩

- Juan Gonzalez, “Puerto Rico’s $123 Billion Bankruptcy Is the Cost of U.S. Colonialism,” The Intercept, May 9, 2017, https://theintercept.com/2017/05/09/puerto-ricos-123-billion-bankruptcy-is-the-cost-of-u-s-colonialism/. ↩

- Miriam Ramirez De Ferrer, “Tax Breaks for Companies in Puerto Rico Don’t Help Islanders,” New York Times, January 23, 1993, http://www.nytimes.com/1993/01/23/opinion/l-tax-breaks-for-companies-in-puerto-rico-don-t-help-islanders-079193.html. ↩

- Yaisha Vargas, “Puerto Rico Watches Corporate Tax Breaks Finally Expire,” Puerto Rico Herald, May 25, 2005, http://www.puertorico-herald.org/issues2/2005/vol09n23/PRWatchCorpTax.html. ↩

- The Dominican Republic-Central America FTA (CAFTA-DR) is the first free trade agreement between the United States and a group of smaller developing economies: our Central American neighbors Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, as well as the Dominican Republic. ↩

- Heriberto Martinez-Otero, and Ian Seda-Irizarry, “The Origins of the Puerto Rican Debt Crisis,” Jacobin, August 10, 2015, https://www.jacobinmag.com/2015/08/puerto-rico-debt-crisis-imf/. ↩

- Derisively called “La Junta”, or in Spanish, “La Junta de Control Fiscal” (JCF). ↩

- H.R. 4900 PROMESA-Puerto Rico Emergency Financial Stability Act of 2015, https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/4900/all-info (accessed June, 2017). ↩

- Puerto Rico Emergency Financial Stability Act of 2015. ↩

- Carlos García, and José Ramón González, “Pirates of the Caribbean: How Santander’s Revolving Door with Puerto Rico’s Development Bank Exacerbated a Fiscal Catastrophe for the Puerto Rican People,” Hedge Clippers, December 13, 2016, http://hedgeclippers.org/pirates-of-the-caribbean-how-santanders-revolving-door-with-puerto-ricos-development-bank-exacerbated-a-fiscal-catastrophe-for-the-puerto-rican-people/. ↩

- José Delgado, “New Administrator of the Government’s Finances,” El Nuevo Día, October 1, 2016, https://www.elnuevodia.com/english/english/nota/newadministratorofthegovernmentsfinances-2246865/. ↩

- Manuel Avilés-Santiago, “Lamento pixelado: Tras el código memético de la patria digital,” YouTube video, https://youtu.be/2Is1orVGWck. ↩

- Hito Steyerl, “In Defense of the Poor Image,” E-flux Journal 10 (November 2009), http://www.e-flux.com/journal/10/61362/in-defense-of-the-poor-image/. ↩

- Steyerl, “In Defense of the Poor Image.” ↩

- The Lares Uprising (El Grito de Lares) was a rebellion against Spanish colonial rule in Puerto Rico, planned by national heroes Ramón Emeterio Betances, Segundo Ruiz Belvis, Mariana Bracetti (who famously sewed the flag), amongst others. ↩

- “IV Poly/Graphic San Juan Triennial: Latin American and the Caribbean,” E-Flux, October 4, 2014, http://www.e-flux.com/announcements/30560/iv-poly-graphic-san-juan-triennial-latin-american-and-the-caribbean/. ↩

- “#elmemestaenlatrienal 4ta. Trienal Poli/Gráfica,” 80grados, October 23, 2014, http://www.80grados.net/elmemestaenlatrienal-4ta-trienal-poligrafica/. ↩

- Translated to English by author; “hacer visibles los procesos de reciclaje y desplazamiento de la imagen, sino ejercerlos activamente. Entendemos el término “exposición” como un proceso de pensamiento y creación de discurso a través de la imagen.” ↩

- The website for the triennial can be found at www.trienalsanjuan.com. ↩

- Marcis Pechio, “La batata y usted: entrevista al chico batata,” La Marginal, May 5, 2017, http://lamarginalpr.com/la-batata-y-usted/; Translated to English by author: “(…) creo que últimamente a mi me ha sorprendido la proliferación de utilizar el medio del meme para la politización, tanto de manera irrelevante como de manera más radical. Eso me parece para nada algo que uno puede echar a menos, porque a veces uno está bien perdido en que uno está sometido bajo ciertas fuerzas. Yo no digo que lo que hice fue una cosa sumamente radical. Para nada. Pero definitivamente le dió una cosquilla a la gente en un lugar que les hacía falta.” ↩

- Translated to English by author: “La clase política para mi, no sirve de nada, asi que deberiamos, inclusive, eventualmente trascender llamar a esa gente batata. Porque, it’s giving batatas a bad name.” ↩

- Translated to English by author; “Somos un grupo historiográfico, memético y feminista. Favor de adscribirse a tópicos de la conquista española (y otras potencias imperiales), arte antiguo a prerrafaelita, tópicos marítimos anteriores a embarcaciones de metal, celebraciones de Regatas y barcos de vela o relacionados a culturas prehispánicas.” ↩

- Translated to English by author; “Frente amplio para la liberación de Puerto Rico y todas sus tierras, independencia hasta la muerte, hopefully la conseguimos antes de que llegue a eso.” ↩

- Translated to English by author; “La Primera y Más Reconocida Organización Isladecabrina para la difusión y discusión del Séptimo Arte.” ↩

- Goya Foods is a Hispanic brand of food items that got its start in Puerto Rico in 1936, and is headquartered in Secaucus, New Jersey. ↩

- Taíno Indians were the principal indigenous people inhabiting the Greater Antilles (Cuba, Jamaica, Hispaniola and Puerto Rico) during the 15th century. ↩

- https://www.loc.gov/collections/web-cultures-web-archive/about-this-collection/ (accessed June 2017). ↩

- According to the OAIS (Open Archival Information System) reference model framework, a compliant archive consists of an organization that has “accepted the responsibility to preserve information and make it available to a designated community”, including “sufficient control of the information provided to the level needed to ensure Long-Term Preservation” and the following of “documented policies and procedures which ensure that the information is preserved against all reasonable contingencies, and which enable the information to be disseminated as authenticated copies of the original, or as traceable to the original”; CCSDS, Reference Model For An Open Archival Information System (OAIS) Magenta Book, June 2012, https://public.ccsds.org/pubs/650x0m2.pdf. ↩

- About LOCKSS, History, https://www.lockss.org/about/history/ (accessed June, 2017). ↩

- Naomi Waltham-Smith, “Rogue Scientists Race to Save Climate Data,” Wired, January 19, 2017, https://www.wired.com/2017/01/rogue-scientists-race-save-climate-data-trump/. ↩

- Update on the Twitter Archive at the Library of Congress, January, 2013, https://www.loc.gov/static/managed-content/uploads/sites/6/2017/02/twitter_report_2013jan.pdfAccessed (June, 2017). ↩

- Kimberlee Morrison, “How Many Photos Are Uploaded to Snapchat Every Second?” AdWeek, June 9, 2015, http://www.adweek.com/digital/how-many-photos-are-uploaded-to-snapchat-every-second/. ↩

- North Carolina State University Libraries, “Social Media Archives Toolkit” https://www.lib.ncsu.edu/social-media-archives-toolkit (accessed June 2017). ↩

- Cathy Marshall, “Whose Content Is It Anyway? Social Media, Personal Data & the Fate of our Digital Legacy,” Video uploaded to the Library of Congress Webcasts. http://www.loc.gov/today/cyberlc/feature_wdesc.php?rec=5581 (accessed June 2017). ↩

- Trevor Owens, Conclusions draft for “Theory & Craft of Digital Preservation,” https://docs.google.com/document/d/1eUlT0JUDdpUOgy0x5Mdv7MxUjVAyz6erEoqpPkqvZEE/edit (accessed June, 2017). ↩

- Chief Information Officer, Oficina del Principal Ejecutivo de Información de Puerto Rico. “Guia para la digitalizacion de documents Versión 1.0,” http://www2.pr.gov/GobiernoAGobierno/Documents/Sistema%20Central%20de%20Gestion%20Documental%20rev%202011-03-08.pdf (accessed June 2017). Translated from Spanish by author: “Programa de Administración de Documentos Públicos de la Rama Ejecutiva del Gobierno de Puerto Rico.” ↩

- UPRM Digital Institutional Repository, https://dire.uprm.edu/ (accessed June 2017). ↩

- Mariela Fullana-Acosta, “Despojan de fondos a las entidades culturales,” El Nuevo Día, June 29, 2017, https://www.elnuevodia.com/entretenimiento/cultura/nota/despojandefondosalasentidadesculturales-2335725/. ↩

- Translated to English by author: “que todo lo local se da en contrapunto al dictamen y régimen visual exterior, pero creo que hay estilo e inteligencia y una geometría bastante calculada en lo que se plantea aquí, recursos y oportunidades a las que apuesto y que juro son y serán fundamentales a la hora de plantearemos nuevos caminos y formas de vernos y recrearnos.” E-mail interview, June 5. ↩

- Olia Lialina, “A Vernacular Web, The Indigenous and the Barbarians,” http://art.teleportacia.org/observation/vernacular/ (accessed June, 2017). ↩