Issue 15: Spectacle East Asia (Fall 2010)

In the Fall of 2008, when our colleagues in the Program in Visual and Cultural Studies at the University of Rochester began formulating the theme of the “Spectacle East Asia: Publicity, Translocation, Counterpublics” Conference, from which this issue’s contents are drawn, most of us had the Beijing Summer Olympics closely in mind. Having just witnessed much discussion in both academia and the mainstream press about the “spectacular” nature of the Beijing Games, it seemed prudent to investigate what was meant by this newest version of our old cultural studies warhorse, the Spectacle. For example, David Barboza wrote of Zhang Yimou’s opening ceremonies in the New York Times: “Nearly two years in the making, [Zhang’s] spectacle is intended to present China’s new face to the world with stagecraft and pyrotechnics that organizers boast have no equal in the history of the Games.”1 China’s “new face to the world,” however, was not limited to its reputation abroad; its (self-) representation through the “spectacle” of the Games, according to commentators, was to have a profound effect on the way the nation and its constituents understand themselves. China’s ascension in this decade to a leading—perhaps the leading—actor in international geo- politics was reflected in the fact that, in the Summer of 2008, the world’s eyes were focused on Beijing. How China understands itself was thus not only mediated by how it represented itself to the “world” through the Games, but also in the very fact of spectacle itself, that is, in being seen. As Kevin Caffrey argues, in China, the Games “became an issue of educating young people to take their place as members of a world community of nations.”2

The spectacle of the Beijing Games thus impacted social life on both the domestic and global registers, and established the global arena as the ground of domestic social relations. In his epilogue to a special issue of The International Journal of the History of Sport devoted to the 2008 Olympics, Caffrey refers to this interpretation of the Games as a “productive spectacle,” and other articles in the issue work to establish the interconnection of global media images with specific local concerns.3 Following from the central thesis of Caffrey’s issue, that abstract global forces, international geo-politics, and worldwide media are productive in the sense that they bring people together in a manner that impacts the sociality of everyday life (a point well taken here), this concept of a “productive spectacle” seems to fly against Guy Debord’s original characterization of spectacle as a device founded on separation.

–

In The Society of the Spectacle, Debord defines spectacle as “a social relationship between people that is mediated by images.”4 “The fetishistic appearance of pure objectivity in [these] spectacular relationships,” he continues, “conceals their true character as relationships between human beings and between classes.”5 Debord’s target in his influential 1967 text was a “reigning economic system” whose basis lay in the isolation of the subject, a system for which spectacle was deployed as its “perfect image.”6 With now more than forty years distance from Debord’s observations, it is our goal in collecting the essays and video art works that comprise Spectacle East Asia to explore the social life of spectacle, as it exists in contemporary China, Japan, and South Korea, and to revisit and reconsider the critique of spectacle by Debord and the numerous scholars who followed his lead. To invoke Debord’s famous line for a second time, might a social relationship between people through the mediation of images also possibly result in productive modes of sociality if the apparatus is not one of monolithic, integrated spectacle and its emphasis is reoriented from the atomization of the subject-turned- bourgeois consumer? Furthermore, might this possibility already be present in Debord’s thinking?

In contrast to many of his successors, spectacle, as articulated by Debord, was not visual at its core. For Debord, the “images” that mediate the subject of spectacular society’s material social relations constituted rather an imaginary, which is to say that spectacle bespeaks a fictitious, represented world that masks the alienation of an actual world dominated by advanced capitalism. In the social theory of more recent decades, the concept of the imaginary has proven useful in theorizing social life as it is mediated through forms of cultural exchange across space and time. For thinkers such as Benedict Anderson, Michael Warner, and Charles Taylor, print technologies and other communicative media enable a mode of discursive sociality among participants who may or may not be proximate to one another.7 Like Debord’s spectacular society, the social imaginary also bespeaks a kind of imaginary world, and its basis is also in culture as experienced through media. Taylor characterizes the social imaginary as “the ways people imagine their social existence, how they fit together with others, how things go on between themselves and their fellows, the expectations that are normally met, and the deeper normative notions and images that underlie these expectations.”8 Here, we return to the visual: while the respective “images” discussed by Debord and Taylor are not necessarily visual, the conditions of the contrasting imaginaries that they theorize have their respective bases in the dissemination of culture through a media apparatus that has become with each decade ever more visual.

It is not our goal here to transvalue Debord’s terms, nor do we wish to “correct” his critique of spectacle with the social theory of later decades. It furthermore will not suffice to simply pose a critical, ad hoc or guerilla “counter-spectacle” to the affirmative, integrated spectacle that Debord describes. Rather, this issue proceeds from the pursuit of the modes of sociality that, for Debord, are effaced but always nonetheless present in the experience of spectacle. In The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere, Jürgen Habermas counterposes “critical publicity” with “manipulative publicity,” tracing the function of mass media “to obtain the agreement or at least acquiescence of a mediatized public” in the service of private interests.9 I invoke this opposition not to repeat the well-worn and too easy binary of critical and affirmative culture, nor even to advocate for a (re-)appropriation of the means of media dissemination—though surely it is a worthwhile goal—but because there lies in Habermas’s formulation a stress on the role of the public. Hijacking the spectacular apparatus is only the first step in recup- erating spectacle; the sociality embedded in spectacle ultimately lies in a different kind of production: not in the production of images in the literal sense, but in the production of an imaginary. For what makes the public public in Habermas’s sense is not that it receives publicity but, rather, that it constitutes and thus produces publicness.10 Herein lies the rational-critical debate that subtends Habermas’s theorization of the public sphere.

In the 21st century, new communicative technologies have augmented the bourgeois public sphere first described by Habermas almost fifty years earlier. The rapid growth of mass media in the second half of the twentieth century, particularly television, remained for the most part a means for one-way communication. However, the popularization of the internet in the last decade has enabled almost instantaneous discussion across great distances and has made cultural producers out of people who would have been, twenty years earlier, only consumers of information. One thread that runs through the essays that comprise this issue is the self-orientation of the cultural practices they analyze to the West. What Pheng Cheah had called, with some trepidation, “a global civil society or an inter- national public sphere” seems clearly to be one intended target of the counterpublics described by Hyejong Yoo and Caitlin Bruce, whether or not a truly global audience in fact exists.11

–

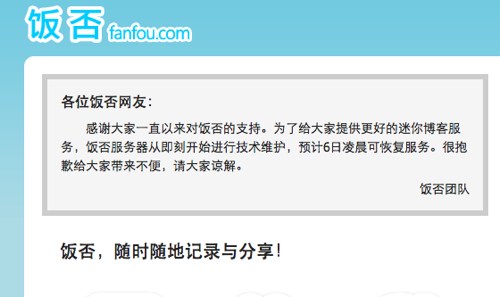

We began to work on this issue in the Summer of 2009, in the weeks leading up to the twentieth anniversary of the Tiananmen Square protests and massacre in Beijing. In response to the Chinese government’s blocking of social media websites such as Twitter, Facebook, Flickr, and even Hotmail in order to control the dissemination of information from Beijing to the rest of the world, local social media sites such as the now-dormant Fanfou.com—an almost exact replica of Twitter—invented a national holiday on June 4th, 2009 called “Chinese Internet Maintenance Day.” These websites erected splash pages with satirical messages such as: “In order to provide better service, the Fanfou server will undergo technical maintenance, effective immediately. We expect to resume service before dawn on the 6th of June,” while making the rest of their sites inaccessible for the days surrounding the anniversary. As with the Beijing Games, the Chinese government sought to preempt dissent around the June 4th anniversary, and, also like the Games, its stress was two-fold: on the one hand, the “Great Firewall of China” was aimed at curtailing the ability of dissidents to self-organize, while at the same time attempting to control China’s reputation and public image abroad.

Fig. 1. Splash page from Fanfou.com, screenshot, June 2009.12

I read this gesture as a barricade of sorts. Conspicuously absent of any hyperlinks, the splash pages denoting “Chinese Internet Maintenance Day” block all inroads from the “information super- highway,” redoubling the Chinese government’s own barricade to restrict public discussion. To these eyes, they also evoke the barricades of 1989. To say nothing of the literal barricades erected to block the advance of the People’s Liberation Army in the days leading up to the events of June 4th, most of us most vividly remember the Tiananmen Square protests and massacre by the photographic or video image of a lone man’s human barricade before a queue of four Chinese tanks. In a recent study on photography in public culture, Robert Hariman and John Lucaites refer to the iconic photograph as a “democratic spectacle,” arguing that its afterlife “subordinates Chinese democratic self-determination to a liberal vision of global order . . . that reinforces individualism and apolitical social organization” and represents “a progressive celebration of human rights while also limiting the political imagination regarding alternative and perhaps better versions of a global society.”13

The “Maintenance Day” barricades reflect the limits of democratic spectacle exemplified by the famous tank photograph, marking the very same absence of politically-engaged and necessarily collective social organization that Hariman and Lucaites identify in the ideology of Western liberal democracy. Here we see a virtual community of dissent, whose collective action is waged not as an explicit political program, or in the name of a sectarian party politics, but is marked, rather, by the voluntarism of a mediatized public arena in peril. I propose a dynamic form of spectacle at play here: we do not know which site first “underwent maintenance” at the beginning of last June, and by all accounts “Chinese Internet Maintenance Day” arose in an ad hoc manner. We presume that some of these sites may have been in communication with one another, but it stretches credulity—particularly as the lines of communication may have been monitored and restricted by the Chinese government— that the observance of this “holiday” en masse was the result of scrupulous planning by an underground cadre of internet radicals.14 Instead, we see here a politics in process, engaged above-ground and in plain sight: the dynamism I have identified has its basis in spectacle’s constitutive properties of seeing and being seen, in which a potential actor views a website declaring itself under maintenance and repeats the gesture on his or her own site, often redeploying the message—“We are undergoing maintenance on the days before and after June 4th, 2009”—with its own phrasing, irony, and wit.

The significance of “Chinese Internet Maintenance Day” for my purposes here is a kind of site-specificity that it displays: its part- icipants are mostly limited to Chinese language websites and, framed as a satirical national holiday, its public consists of those whom we might call the “netizens” of China. Furthermore, its stakes are mnemonic—its barricade is also a disguised monument com- memorating the violent June 4th repression—but the form of memory that it aims to preserve is not international, but rather local. “Maintenance Day” is not as readily assimilable to a narrative of individual, Western liberal democracy as the iconic image of the lone man before the tanks because the form and poetics of its publicity necessitates reproduction by its intended (local) public and is, thus, participatory in nature. Its goal is to effect a collective recognition by its intended public that its constituents do in fact constitute a public, which I want to distinguish from the more conventional international distribution of power that we encounter in subaltern activist appeals to what we might call an international or global public sphere (e.g., the circulation of the iconic tank image from the Tiananmen protests among first world actors arousing cosmopolitan concern and the subsequent international, but predominantly Western, shaming of the Chinese government for its “backwards” attitude towards civil liberties).

There are two distinct social imaginaries at play here. In the case of “Maintenance Day,” we have the self-declaration of a social imaginary as an activist public. Meanwhile, the “democratic spectacle” that Hariman and Lucaites describe abstracts local self- determination to reinforce the commonsense liberal ideals of an international cosmopolitan class, whose own social imaginary purports to give voice to imagined, unfortunate others: to empower the powerless by shaming the perpetrators in the international public arena. The rhetoric of international shaming brings us back to David Barboza’s New York Times article on Zhang Yimou’s opening ceremonies, which I quoted at the beginning of this introduction. In it, Barboza refers to Zhang as a “Chinese Leni Riefenstahl.” The implication, of course, is a comparison between the Beijing Games and the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, between Zhang and the fascist spectacle of the Third Reich, and, if we follow this comparison further, between the Chinese government and Hitler, Goebbels, et al. While not quite the Tea Party, I contend that Barboza‘s implied comparison is reckless and irresponsible and, furthermore, that such a comparison rests on our indelible collective memory of that image of the lone man and the four tanks, and on the narratives of Western liberal democracy that this image anchors.

The “Maintenance Day” barricades echo a different image of self-sacrifice from Tiananmen Square, one that can also be read as a barricade: the Goddess of Democracy statue erected in the Square— facing the portrait of Chairman Mao—by students from the Central Academy of Fine Arts on May 29th, 1989. Wu Hung stresses the distinctness between the Goddess of Democracy and the American Statue of Liberty, to which its physical form alludes. The statue, Wu writes, intentionally and distinctly represents a young Chinese woman, and became an image for collective identification among the protesters: “Soaring above the cheering demonstrators, she was immediately understood by everyone in the Square: ‘She symbolizes what we want,’ explained a young worker. Then, stabbing his chest, ‘she stands for me.’”15 The Goddess statue differs from the more famous “tank man” image both in terms of the collective mode of its construction and because, unlike the lone figure before the tanks, the statue was surrounded by protesters, seemingly draped in their flying banners.

The Goddess statue’s mode of publicity, Wu argues, was in its status as a temporary monument: “a monument that was intended to be destroyed,” the product of “an attempt to carry out a kind of planned suicide.”16 The Academy students purposely built the statue as large as they could so that it could not be easily removed—indeed, the statue was ultimately plowed into and toppled by a tank, in Wu’s words “lying together with those murdered youths.”17 “Chinese Internet Maintenance Day” was also a temporary monument, marking the Chinese government’s repressive censorship in the days leading up to the anniversary with a euphemistic self-sabotage. However, while its self-censorship repeated that of the Chinese government but in a more plainly observable manner, its memorial function takes on another sense of “seeing.” To follow the theme of memorialization also engaged in Okwui Enwezor and Hyejong Yoo’s contributions to this issue, the internet barricade observed the prohibited anniversary of June 4th under the guise of a national holiday, each site forcing its visitors to observe the holiday—to see that the site is down is already to have observed “Maintenance Day”— while at the same time impelling the visitors to observe both the disguised anniversary and its prohibition. As previously stated, the moment of this multivalent “observation” then enters into a dynamic process of reduplication, and in turn remakes the government barricade against its intention, into a site of public debate. At the same time, the multi-sitedness of the “Maintenance Day” barricades counters both the ubiquity of the government’s integrated spectacle and the omnipresence of its surveillance apparatus, not only adding the condition of being observed to observing (as in Habermas’s opposition of critical and affirmative spectacle), but placing the two in dialectical relation.

–

The essays that comprise Spectacle East Asia each contribute to a larger understanding of contemporary spectacle that is rooted in the social. Okwui Enwezor looks at two anniversaries—the 40th anniver- sary of May ’68 as he was curating the 2008 Gwangju Biennale and the 15th anniversary of the May 18, 1980 Gwangju uprising in South Korea that the Biennale was founded in 1995 to commemorate—and counterposes the commemoration of May 18, whose “events of resistance . . . are still marked on the present,” to the retrospective rhetoric of avant-gardist revolution and narratives of universal liberation (and heroic failure) that have both falsified a true memory of May ’68 and rendered it (merely) historical. From his thoughtful analysis of how the historical event of May 18 resonates with present concerns, Enwezor examines how the building of cultural institutions in South Korea based on the commemoration of spectacular street protests comes to engender local debate while mediating the local with the global arena.

Hyejong Yoo’s essay on the 2008 Candlelight Vigil protests in Seoul also reflects on the spectacle of protest. Her argument departs from a critique of conventional politics and illustrates the manner in which the nation—an unfashionable and seemingly regressive concept in our so-called cosmopolitan age—was, for the Candlelight protesters, a counter-figure waged against the global economic interests of the South Korean state. The actions of President Lee Myung-bak’s government, she contends, were interpreted by the protesters as acting against the “national” interest and, thus, a “rhetoric of purity” emerged in which conventional, ethnic-based nationalism was replaced by a nationalism in which “purity” stood for the democratic civil society promised by the nation-state’s constitution and reflected in the memories of the democratic protests of May 18, 1980 and June 10, 1987. This fundamentally rights-based protest, disguised as a recuperated nationalism, presents a com- pelling and forceful reading of the poetics of tactical spectacle in the internet age, and the manner in which those in want of political agency might mobilize it.

Enwezor and Yoo both begin from the relatively recent industrialization and global-economic ascendancy of South Korea; Rika Hiro revisits a similar moment in Japan in the 1970s. The “Spectacle East Asia” Conference ended with the observation that its two papers on Japanese topics concerned the art of the ’70s while its only Japanese video art submission (the ethnically Korean, Japanese- born and raised artist Kwak Duck-jun’s Self-Portrait ’78) was from the ’70s. With the recent international prominence of first Chinese, then Korean art, had Japan, I wondered, been relegated in East Asian cultural discourse to the historical?

It is tempting to account for our conference’s unintentional emphasis on Japanese art from the ’70s (as well as the larger cultural trend that it symptomizes) by looking at contemporary Japanese culture’s earlier moment of “contact” with the West, but Hiro’s essay on the Japanese art group Video Earth provides us with a model that complicates this kind of Western cultural determinism. Her essay analyzes Video Earth’s basis of its collectivity around the democratic potential of the video medium, reading the formal characteristics of video (as opposed to those of photography) alongside the social possibilities of the newly available technology. Japanese modernity, she argues, created new economies of vision based on a redefinition of the public and private spheres. She uncovers a kind of publicity in Nakajima Kō’s “self-censorship” of Video Earth’s dual-projection video work What is Photography? (the work would have violated obscenity laws if shown publicly), a publicity that is intimately tied to Japanese modernization and which cannot be reduced to international art trends and movements, or to the precedence of Nauman and Graham, Chelsea Girls, even Paik.

Caitlin Bruce returns us to the present and analyzes graffiti culture in 21st century Beijing and Shanghai in relation to the branding and marketing of the new Chinese mega-city. She begins from the premise that a truly social space must depart from its branded international image (mianzi, or “face value”) and engage its inhabitants in local, face-to-face social relations.18 Exploring the competing impulses of nationalism and globalization in contemp- orary Chinese urban planning, Bruce proposes local graffiti culture as a counterpublic reclamation of city space in response to its commodification by state and corporate interests.

In 1987, Krzysztof Wodiczko characterized the Situationist International’s strategies of détournement and dérive as a “public intervention against spectacle” and a “tendency toward alternative spectacle.” This alternative spectacle, he argued, engaged in the “manipulation of popular culture against mass culture.”19 At stake here is the opposition that Wodiczko draws between popular culture and mass culture, between the public and integrated spectacle. Spectacle, in its guise as the late-capitalist boogeyman of cultural studies at the end of the 20th century, was a device aimed to deceive and control the masses. The undifferentiated masses, following its various definitions by cultural critics such as Siegfried Kracauer and Raymond Williams, must be rendered specific, re-embodied in their physical and social localities as people—i.e., the antecedent of both the public and of popular culture.20 The goal of the essays in the following pages is to explore the parameters of this definition of people, and to investigate and theorize the deployment of a larger definition of spectacle in its name.21 The authors of Spectacle East Asia follow spectacle down many roads: from the rarefied seats of high finance and urban planning to the graffiti-laden walls of soon-to-be- gentrified neighborhoods, from World Expositions and international art fairs to impromptu art galleries whose doors cannot be opened to the public, from sites of large-scale political protest to internet message boards. Together, they pursue what I take to be the utopian moment in Debord: in giving La Société du spectacle its name, he must have envisioned some room for a social life within it.

- David Barboza, “Gritty Renegade Now Directs China’s Close-Up,” in New York Times (August 7, 2008). http://www.nytimes.com/2008/08/08/sports/olympics/08guru.html (last accessed June 2010). ↩

- Kevin Caffrey, “Epilogue: Approaches to a Productive Spectacle,” in The International Journal of the History of Sport 26:8 (July 2009), 1147. ↩

- In addition to Caffrey’s epilogue (cited above), see also: Xuefei Ren, “Olympic Beijing: Reflections on Urban Space and Global Connectivity,” and Hua Guangtian, “Olympian Ghosts: Apprehensions and Apparitions of the Beijing Spectacle,” both from the same issue. ↩

- Guy Debord, Society of the Spectacle (1967), trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith (New York: Zone, 1994), 12. ↩

- Ibid., 19. ↩

- Ibid., 22, 15. ↩

- See: Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities (New York: Verso, 1983); Michael Warner, The Letters of the Republic (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990), and Publics and Counterpublics (New York: Zone, 2002); and Charles Taylor, Modern Social Imaginaries (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004). ↩

- Taylor, 23. ↩

- Jürgen Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere (1962), trans. Thomas Burger (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1989), 177-178. ↩

- For a discussion of this passage in Habermas and the coining of the neologism “publicness” as the term “publicity” began to be inextricable from consumer culture and advertising, see: Sven Lütticken, Secret Publicity: Essays on Contemporary Art (Rotterdam: NAi Publishers, 2006), 28-30. ↩

- Pheng Cheah, “Introduction: The Cosmopolitical—Today,” in Cosmopolitics: Thinking and Feeling Beyond the Nation, eds. Pheng Cheah and Bruce Robbins (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1998), 37. In the same volume, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak reminds us that uneven access to the internet and uneven levels of media literacy across the globe render the “global” largely—and hegemonically—Euro-American, as she sarcastically declares: “Hail to thee, pax electronica.” Spivak, “Cultural Talks in the Hot Peace: Revisiting the ‘Global Village,’” in Cosmopolitics, 332. ↩

- “Thank you for your continued support of Fanfou. In order to provide better service, the Fanfou server will undergo technical maintenance, effective immediately. We expect to resume service before dawn on the 6th of June. We apologize for the inconvenience and hope that you understand.” ↩

- Robert Hariman and John Lucaites, No Caption Needed: Iconic Photographs, Public Culture, and Liberal Democracy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), 209. ↩

- One estimate counts 393 websites participating in “Chinese Internet Maintenance Day.” http://cnreviews.com/life/events/chinese-internet-maintenance-day_20090604.html (last ac- cessed June 2010). ↩

- Wu Hung, Remaking Beijing: Tiananmen Square and the Creation of a Political Space (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005), 46. ↩

- Ibid., 49. Emphasis is in the original. ↩

- Ibid., 46. ↩

- This definition of mianzi/”face value” (面子) is intimately connected to public image. In Chinese, to “give face” is to publicly show respect, and here “face” takes on a meaning similar to that of the English idiom “save face.” ↩

- Krzysztof Wodiczko, “Strategies of Public Address,” in Discussions in Contemporary Culture, ed. Hal Foster (Seattle: Bay Press, 1987), 44. ↩

- See: Siegfried Kracauer, “The Mass Ornament” (1927), trans. Barbara Correll and Jack Zipes, in New German Critique 5 (Spring 1975); and Raymond Williams, Culture and Society: 1780-1950 (London: Chatto and Windus, 1958). ↩

- The Chinese renmin (人民) and Korean minjung (민중) have their distinct historical and discursive resonances—renmin has its indelible association with the communist ideologies of the People’s Republic while minjung, as exemplified in Hyejong Yoo’s contribution to this issue, is inseparable from the nation’s democracy movement—but the general sense of “people” to which both terms speak underlies both the fluidity of people that I am identifying here, and the possibility of imagining in these terms new or alternative modes of sociality. See also: Sohl Lee’s engaged discussion on the rethinking of renmin and minjung in her curatorial statement in this issue, to which I happily defer on this topic. ↩