Written By Jacqueline Witkowski

“Sometimes the war news seems so abstract and it’s hard to imagine what it’s like for soldiers—knitting helped make it real to me.” 1

Left in the visitor’s notebook, this statement commented on Sabrina Gschwandtner’s Wartime Knitting Circle (2007), an interactive installation that invited the audience to sit down with the artist and other gallery attendees to discuss the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan while choosing from a variety of “wartime” knitting patterns: squares for blankets to send to Afghanistan and stump socks for those who suffered from casualties.

Fig 1. Sabrina Gschwandtner Wartime Knitting Circle, 2007. Acrylic, cotton, wood, various knitting notions, Dimensions variable Photo by Alan Klein, courtesy of the Museum of Arts and Design, New York.

In 2012, the Renwick Gallery in Washington, D.C.—a Smithsonian dedicated to American craft from the 19th century to present—unveiled the exhibition, Craft Futures: 40 Under 40, of which Gschwandtner’s work was a part. Curator Nicholas R. Bell argues that it was this generation—the forty artists featured—who were the most directly influenced by the events of September 11, 2001 (as the oldest were 29 years old and the youngest only 17). Bell states “the 9/11 attacks fundamentally altered the experience of everyday life for all Americans, but particularly for those in their formative years…”2Within the events of September 11th, there came the widespread digital surveillance and its own ongoing war. This war incorporates the domain of the Internet, where whistleblowing uncovers en masse the documents, videos, and secreted dialogues and posts them for an unequivocal public access. If this is the legacy of September 11th, as the digital becomes a normative tool for information emission, then what occurs when the medium of knitting is moved from a tactile craft and into the digital domain?

Craft, war, and politics intersected long before Gschwandtner’s knitting circles, or other artists’ work such as Dave Cole’s Evolution of the Knitting Needle through Modern Warfare (2000-2005), or Marianne Jorgensen’s Pink M.24 Chaffee (2006)—artists also featured in the Craft Futures exhibition. The instances tying craft and activism existed prior to when artist Betsy Greer coined the term “craftivism” in 2001. The term took hold with crochet, knitting and quilting, and Greer attributes the term to the post-9/11 War on Terror campaign and the formation of the group, “Church of Craft,” with a mission to “create an environment where any and all acts of making have value to our humanness.”3 Images such as the concept of “knit bombing” come to mind, where various items found on the streets are covered in colourful, knitted yarn: trees, fire hydrants, posts, even bicycles are obscured in multi-colored swatches.

Fig 2. Knit bombing on Main Street, Vancouver, British Columbia (2014) photo by Margaret Stern

But in 1981—20 years before Greer and knit bombing—a group of knitters joined the woman-only action in Berkshire, England, and protested against nuclear warfare and the installation of American cruise missiles at Greenham Common Royal Air Force Base.4 Then, at the onset of the 21st century, there were protests involving knitters in Montreal against the passing of the Free Trade Area of the Americas Agreement, in Prague with the meeting of the World Trade Organization/International Monetary Fund, and in Calgary with the G8 summits. While not overly political or engaged in direct political action, these Revolutionary Knitters chose their targets and pushed against capitalist agendasfurther highlighting how the “resurgence of ‘feminine’ knitting” became “much more intertwined with the changing ‘masculine’ economy.”5 Lisa Anne Auerbach’s Warm Sweaters for the New Cold War (2004-ongoing) juxtaposed the infamous image of a hooded Abu Ghraib prisoner with rhetoric of the Bush administration, calling attention to the very impassioned and in turn, violent, approaches taken post 9/11.6

Craftivism, in turn, has become a tool for artists to critique grandiose military spending, nuclear armament, and call attention to a war machine that supports cultural and national hegemonies. Therefore, I will highlight an implicit link between the act of knitting and the industrial war complex; a relationship that, in an indirect manner, has furthered a gendered participation and has been problematized by artists Cat Mazza and Kristen Haring as they formulate a digital and coded mediation into their knitted projects. These projects complicate women’s perceived historical roles in war: no longer are women seemingly protesting through their knitting, but rather their knitting contributes to wartime activity. Furthermore, cotemporary forms of warfare, such as the ongoing digital war between the state and hackers resituates how new frames of war are evoked. To rethink just how the hand is related to machinery, or the hand to craft and the machine to war, it is plausible to refer to the 19th century Marxist critique concerning freedom, the individual, and capitalism. In a report to the Congress at Brussels in 1868, Karl Marx states,

Another consequence of the use of machinery was that it entirely changed the relations of the capital of the country. Formerly there were wealthy employers of labour, and poor labourers who worked with their own tools. They were to a certain extent free agents, who had it in their power effectually to resist their employers. For the modern factory operative, for the women and children, such freedom does not exist, they are slaves of capital.7

What is often seen as women’s work and hobby art had the incredible potential to be politically activated, and particularly for Marx, labour with the machine immediately connected the individual to the capitalist endeavour. Sadie Plant builds on this critique of the relationship with the machine, capital, and war:

This was a brave new equilibrated world of self-guiding stability, pharmaceutical tranquility, white goods, nuclear families, Big Brother screens, and, to keep these new shows on the road, vast new systems of machinery capable of recording, calculating, storing, and processing everything that moved. Fuelled by a complex of military goals, corporate interests, solid-state economies, and industrial-strength testosterone, computers were supposed to be a foolproof means to the familiar ends of social security, political organization, economic order, prediction, and control.8

This is not to say that the handiwork that manifests outside of this gainful, commodity-producing labour field is immediately associated to the machine, but rather the lineage of the craft commodity becomes undoubtedly married into a relationship belonging to productivity and the apparatus—a machine that transforms over the course of two centuries to further wartime activity or to constantly prepare for a state of either national or digital war. The “factory,” with its shift to the business model and toward products, became connected to the machine code; and while manufacturing has not entirely shifted to further solely wartime and military production, there is a new constant fear on attacks and hacking. Knitting, a craft that has a long connection to the hand and to the machine, is tied historically to both these practices of hand-knit and machine-knit and can be be understood as existing alongside the capital investment of items for warfare.

The tactile wool, the mere presence of bodies conversing as they knit, and the materiality of the objects, all end as part and parcel to the viewing experiencing when artists connect the act of knitting to the military system. The armoured vehicle, rendered docile by the draped knitted coverlet uses each medium in its finite state: the wool is knitted, the tank assembled. The process and positionality of knitting changes in each project but the act of knitting itself, and the physical manifestations of the medium seem pertinent to how these works engage with the politics of war and capitalism. What happens when knitting, in its seemingly compliant structure—one that is malleable and controllable—becomes coded? If there has been any skepticism about this “hipster hobby” as Julia Bryan-Wilson points out, particularly as it has been “castigated as domestic, quiescent, conservative and trivial…because [it has] traditionally gendered,” how do artists such as Cat Mazza alter this uncertainty when the tactile material turns to the digital platform, altering both the way knitting is typically interacted with but incorporating new media that have their own trajectory regarding warfare and surveillance?9

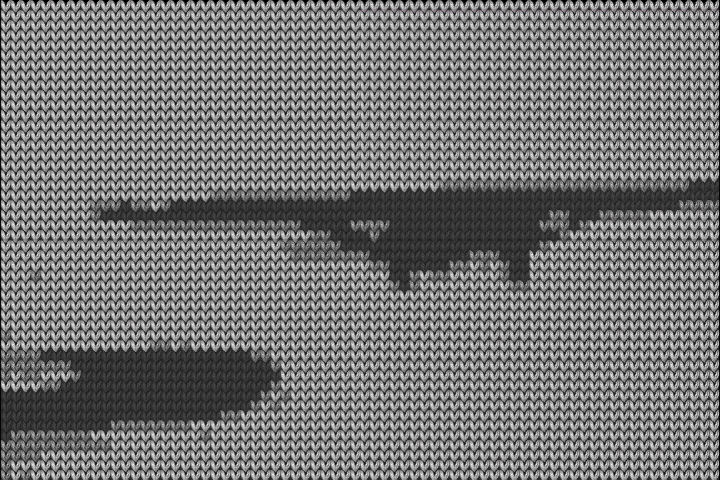

As the grainy images flicker, the colors oscillate between tonalities of grey that obscure bodies jumping out of planes and therefore conceal the abstracted landscapes that slowly appear. In light of the American occupations of Iraq and until recently Afghanistan, or even the ongoing detainment of prisoners at Guantanamo, the subject matter of Mazza’s Knit for Defense (2012) installed as a singular projection seems everyday, banal and innocuous.

Fig 3. Stills from “Knit for Defense” (2012) copyright Cat Mazza

Watching Mazza’s video installation jars the viewer—there is an immediate, but subtle, disjuncture between the medium and the subject. As these images begin to make visual sense, Mazza’s use of the medium encourages, or perhaps forces, a more focused effort in order to see what appears—to legitimate the understanding that the pixelated tonalities of grey are indeed soldiers and the large swatches of colour are landmasses, albeit, ones that oddly appear to be knitted.

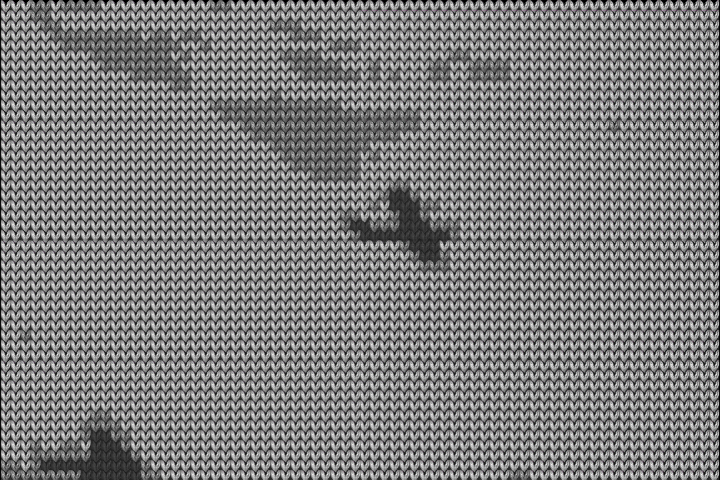

Fig 4. Stills from “Knit for Defense” (2012) copyright Cat Mazza

Fig 5. Stills from “Knit for Defense” (2012) copyright Cat Mazza

Fig 6 . Stills from “Knit for Defense” (2012) copyright Cat Mazza

Fig 7. Stills from “Knit for Defense” (2012) copyright Cat Mazza

Her ambiguity in Knit for Defense stems from the utilization of machine-knitted swatches of these scenes of war, taken from photographs from World War II, Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan, along with aerial footage captured by drones. She uses Knitoscope, a computer program that manipulates the photographed imagery and turns it into video footage that appears to be comprised of knits and purls, actions that occur when inserting the knitting needless through the bottom or top of looped yarn to create two basic stitches. Mazza invented the program herself and blends together two stereotypical tropes: the gendered craft of knitting and the masculinized world of war surveillance.10 Knit for Defense, therefore, plays with a very layered and nuanced history regarding knitting, photography, film and war culture.

Mazza’s larger body of work investigates two aspects of combat. Primarily, she explores the cinema of combat and secondly, her work interrogates how the citizen may or may not have—quite literally—a hand in perpetuating the war effort. The title, Knit for Defense, stems from the World War II effort encouraging women and children to knit sweaters, vests, socks, and other garments to send to England in 1941 and later to American soldiers. Yet this campaign is rooted within the Revolutionary War up until World War I, when the Red Cross distributed over a million pamphlets and held instructional sessions throughout the country to teach young girls to knit.11 On November 24, 1941, LIFE magazine published a five-page spread that urged women to help knit one million standard Army sweaters by Christmas to send to British allies. Furthermore, knitting became a topic of importance when it was utilized as a covert manner to conceal codes; thus, nations refused to allow the exchange of knitting instructions between countries for fear of steganography—or concealed writing. Mazza confronts the interconnections between coding, war, and surveillance through the craft of knitting, and her use of photography calls up the cinema of combat or as historian John Tagg states, “the mechanics of subjection.”12

Yet, as she obscures and manipulates these scenes, whether through turning them into the banal knit—and in turn, a “film”—she offers a new frame in which to highlight the very control that lies within video practices and their role in war. This simultaneously examines just how much control can happen in the digital mediation and handling of cinema, as well as how the ordinary medium of knitting could propagate and encourage such violent imagery, that in turn becomes itself mundane. As Paul Virilio discusses:

“The industrialization of the repeating image illustrated this cinematic dimension of regional-scale destruction, in which landscapes were continually upturned and had to be reconstituted with the help of successive frames and shot, in a cinematographic pursuit of reality, the decomposition and recomposition of an uncertain territory[,] in which film replaced military maps.”13

Under this guise, we must reconsider what is entrenched in these knit stitches as they move into the images of war and are further encoded and embedded—both historically and technologically—as large-scale digitized videos. Mazza’s hand is removed as Knitoscope offers her the ability to compute a moving image into one composed of knits, without ever picking up the knitting needles herself.

Mazza’s emphasis on World War II in Knit for Defense additionally provides a more nuanced look at the shift from discipline society toward control societies. The photographs used in Mazza’s video installations come from those wars that the United States has participated in, and yet, her title stems from a World War II initiative in which the industrialization of the country relied very little to none on the participating human knitters. The Second World War occurred at a time that witnessed widespread industrial production and mainstream availability of knitting and other textiles and thus, there “was far less need for homemade objects and many women knit because women had always knit in wartime.” Therefore, there was a tension between the increased mechanization and the notions of handcraft signifying “home” and “being cared for” for soldiers during wartime. Knitting became “more a symbolic, nostalgic custom and ritual than an actual material necessity.”14 Therefore, civilians, and women in particular, had always contributed to the war effort by knitting helmet liners, socks, sweaters and other accoutrements which provided a semblance of the warm domesticity the soldiers were fighting to defend, and in turn made women feel as though they were dutifully a part of the war effort.

The promotional role of knitting encouraged morale and even in World War I, mothers and loved ones would include notes for their soldiers in the khaki kits and knitted gloves.15 Knit for Defense,” a line that corralled both women and children as part of the rapid wartime manufacturing occurs at a moment when, as Deleuze states on the shift from disciplinary to control societies, “the family is an ‘interior’ that is breaking down like all other interiors—educational, professional, and so on.” 16 This move towards control happens when Japanese Internment Camps began springing up through the western United States, when nuclear armaments were being tested to the point of possible and future detonation, and when women would soon be entering the work force in droves to take on the positions that their husbands, sons, and fathers left. Despite the apparent break down of the factory system at the basic level that they no longer had male labour, this idea that the shift in having female workers ushers in a sense that they, too, can participate in the war effort if even from afar. If the male presence was distinguished from the home, how easy it would be to bring the gendered dynamic into the open and offer a women a place where their husbands had been. Rosie the Riveter and other iconic images of women helping the industrial war complex were connected to female emancipation, but with their concentrated insistence and urgency to knit and participate in the effort, there is an intensity on women’s duty that sees an incoming shift at the level of the government towards that of control. The focus of the government turns to a kind of reform of the factory system that is equal to the business of war. These notions of work and labour in the industrial war complex expand Mazza’s own projects as she knits, or rather, has images machine-knitted for her. This removal of the hand alternates interestingly between the ways the United States encouraged the act of knitting but at the same time, the overhaul of the machine (and Fordism) had taken workers from their twelve-hour work day to the more manageable eight—or in time to be home to see dinner on the table. Reciting Marx’s quote about the inability of women and children to be free from capitalist chains becomes evermore overwhelming in that it highlights how the government apparatus encouraged women to come out of the woodwork, to work in the factories, but just as much to continue the domesticated labour—or what has been traditionally unpaid.17 Their hands in each labour are similar to this shift in what Mazza highlights. They are both very obvious and hidden: obvious in the way that there is now a female presence (and one that is readily encouraged) in the labour force, but hidden, in that this unpaid labour of the knitted garment (of which soldiers have no reliance) reifies the domestic, gendered sphere.

The acknowledgement of the separation and/or freedom from labour is demonstrated in the LIFE magazine spread detailing how to learn to cast on, knit, and purl, but more importantly to urge Americans to contribute to the war effort in Britain, by knitting one million sweaters by Christmas—notably just one month away. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt was frequently photographed knitting, and in 1941, “she boosted national participation by hosting a ‘Knit for Defense’ tea at the Waldorf-Astoria in New York City.”18 The cover of LIFE magazine used a stock photo of a woman knitting. She, a blonde haired, Caucasian woman, looks down at her needles as she works closely on the few rows that she has. Her concentration deflects the viewer’s gaze and she is dedicated to her craft, seemingly pursing her lips with focus.

On the interior portion of LIFE, there are black and white illustrations of a woman’s hands denoted by the carefully manicured and polished nails. Without the visualization of the face, or even the rest of the body, the hand and its labour become metaphorically cemented together. The anonymous and unpaid labour is again tied up in a gendered relationship. That is to say, the directions on how to contribute to the one million sweaters by Christmas— which would have required a skillset out of reach for a novice knitter—provide a connection between the typical labour that women perform as the following pages offer the result of their proposed production. One million sweaters knitted by Christmas names a quantifiable amount that is enacted predominantly, if not solely, by women. The labour that was now entirely obsolete in the industrial war complex has been resituated in order to offer a specifically gendered participation. Remember: “Women had always participated in the war effort through knitting,” notes Bryan-Wilson.19 And while this is factual, the labour regulations and the khaki wool used in regulation sweaters, socks, etc. were hard on women’s eyes as they were scratchy on women’s hands, and soon, factory labour either exploited their participation or completely eradicated it. For example, the Great War saw the demise of ‘luxury’ trades such as dressmaking and millinery.20 Historian Lucy Adlington notes,

Many more thousands of women were also dismissed from the industrial side of the textile trade—the big cotton, silk and wool factories of the north of England and Scotland—which traditionally employed women for roles that were considered ‘female,’ paying them far less than men for their work, but not sparing them the health hazards of factory life.21

Furthermore, women, with the onset of the war and the longue durée of occupation, were now expected to construct kits for soldiers abroad: blankets, sweaters, vests, and socks all came from women knitters.22 Undoubtedly, one must consider the change in socioeconomic situation both between the United States and England during each of the world wars; however, there appears to be a general compliance in the issues that women’s labour of knitting during war efforts was experienced with unwavering enthusiasm. But if Mazza’s Knit for Defense sees the removal of the hand in favour of the installation’s violent mechanized crafted product and digitalization of scenes of war, then these images in LIFE magazine also convey a sense of violence towards the production line, or rather “harmless hobby” which produces hand knit sweaters in a moment that sees the greater mechanization of war. The four rows of four images provide in stark contrast the instructions for women to participate in the military effort in a manner that is indeed historically unrecognized and unpaid.

Each Knit for Defense offers a sense of violence that partakes in the control that the Second World War demonstrated over women’s labour. The later activism evoked by artists in the 1970s or the Revolutionary Knitters in Canada and the Czech Republic, refutes the removal of the hand from its connection to craft and thus, women’s labour. But this dissolution of the hand embellishes on the manner in which code was concealed in knitted patterns, and thus, elevates and expands the ways in which women’s labour becomes hidden in order to further the war effort. As Adlington further highlights on the undocumented and non-regulated workshops that mushroomed up to secure women’s participation, “Sylvia Pankhurst gave the misery a human face in her book The Home Front. It has relentless accounts of women’s seated labour: A mother with six children making seven soldier’s bags in four hours, for which she got 5 1/2d, out of which she to replace the needles broken on the thick fabric; a seamstress earning 2 s 1 d per day for a dozen shirts, but paying 2 ½ d to buy the sewing cotton. For a 42 hour stint, a woman sewing eyelet holes on kit bags was paid only 5s 7d….”23 What is so different in Mazza’s work than others working with craft, or even particularly with knitting, is that she completely eradicates her hand from the process of creation—yet she maintains control over the finalized project. She does not knit her own stitches but rather, the machine works for her to first create a pattern and then to combine these patterns in order to create moving digital images. Coding, in regards to knitting and textile production, functions with a double-entendre. Mazza is involved in a specific mode of code, the binary numbers that entrench the makeup of the program Knitoscope—itself having a pertinent name in relation to surveillance.

While the scholarship relating to hidden wartime codes remains considerably underdeveloped, the phenomenon sees its first appearance in popular culture with A Tale of Two Cities (1859), by author Charles Dickens. Character Madame Therese Defarge, a “mother of the revolution,” used pattern stitches as a code and knitted a list of the upper class doomed to die at the guillotine.24 Supposedly inspired by the “tricoteuses” or “knitters,” Dickens based the character on the women “who attended the National Convention in which the fate of unfortunate rich was debated during the French Revolution, knitting while they listened.”25 Despite involvement of Madame Defarge to take up knitting as a source of code, the use of knitting in espionage has nonfictional roots in the United Kingdom during the Great War. MI-6, a sector of the British Secret Intelligence, employed locals behind enemy lines. In 1914, Belgian professionals who wanted to provide support for their countrymen after the invasion by Imperial Germany began to encourage elderly women to participate. BBC Radio 4 reported, “they would get little old ladies who sat in their houses that happened to have windows that overlooked railway marshalling yards, and they would do their knitting and they’d drop one for a troop train, purl one for an artillery train and so and so on…”26 This enactment led to the Office of Censorship’s ban on posted knitting patterns in the Second World War, in case they contained coded messages.27 But this enactment of placing code inside a knitted pattern oscillates between the perceived gendered dynamics of docile and domestic and surveillance and informative. Women were producing goods that were both significant and entrenched with valuable information as they were enriched with fondness for their loved ones.

Mazza’s project notably plays with the dual definitions of coding that are associated with the industrial war complex. She first uses knit stitches as pixels, and thus highlights the historical connection to the knitted kits for the soldiers that appear in her work. Through the computer coding that operates under Knitoscope, Mazza then sets forth the relationship between the digital and forms of warfare. For artist Kristen Haring, this method becomes evident in her work Subtle Distress (2007), whereby the carrying of messages through the textile is a mechanism of translation between binary systems.

Fig 8. “Subtle Distress” (2007) copyright Kristen Haring

On her practice, Haring states:

I spell out words by switching between the two stitches that make up knitting (knit and purl) like a telegrapher switches an electrical current on and off to send Morse code. With patience, text can be deciphered from the shape of the stitches. This project complicates reading partly to emphasize that all communication depends on cultural codes. Understanding Morse code knitting requires combined knowledge of domains often set apart as masculine and technical, in the case of Morse code, and feminine and folksy, in the case of knitting.28

The case of binary coding in Haring’s work, aligned closely to how Mazza’s work functions, forays into the gendered aspect of textile work and information systems. The masculine images of war, men jumping out of planes and images taken from drones, become the homely knitted projects that only when further encoded become digitalized. For Haring, there is a playful manner in which she uses steganography in her work. Rather than the machine that inputs stitches, her hands become the mechanism and she hides her own messages in the garments.29 If binary systems for Morse code are a set of zeroes and ones, and in the most basic sense stand as the on/off of electrical currents, then the knit/purl exist too as a binary system. “Knit” correlates to the dot or the “on” of electricity, while the “purl” stands for the “off” position of the current or dash. So as Haring knits Morse code, she manipulates the letters into systems of knits and purls, thus creating projects like the SOS sweater—a red crew neck sweater containing emergency distress information.

But why evoke Morse code? Understandably, Haring’s decision is mounted on the two options awarded in knitting— knit and purl stitches—and thus, the binary becomes nothing more than the two states of being that exist, both electrically and in the medium. This set of systems creates a fierce tension on what information is transparent and what is ultimately concealed. To the untrained eye, Haring’s SOS Sweater conveys little, unless (and this would be a stretch) you are an experienced knitter who both recognizes the patterns and more importantly, can identify Morse code. The language system itself is not inherently militarized but it was employed heavily in the Korean and Vietnam wars, as well as in 1941 when the citizens of Northern France, Belgium, and the Netherlands began to tap out the dot, dot, dot dash that would make up the letter “V” – a signal for Victory. Her work falls in line with the entrenchment of code maintained by Madame Defarge and the Belgian grandmothers watching trains through their windows—it is a subtle blend of the power of the gendered craft in times of masculine war machine. This conscious referencing of history by the artists, particularly in relation to the history of World War II specifically, is distinct from other politicized forms of practice. Yet does its covert and concealed manner render it obsolete under the historical problem set of industrialization and masculinized informational systems? For Mazza, this removal of the hand in lieu of Knitoscope only supports the dismissal of the handmade in favour of the machine-made knitted scenes.

This manoeuvre of the hand under these realms of codes creates both a contradictory and complementary conundrum for knitting in times of war. Haring’s work so readily complicates the notion of coding in the sense that she brings both steganography and electronic code into question with her work; however, Mazza too, has a hand in concealing a message about the history of labour in the craft via the images and title she has chosen for her project. Her removal of the hand only begs the viewer to think of how hands have been moved outside the frames of war. These frames, however, are constantly in flux as nations prove that digital warfare happens not just abroad, where drones manage air strikes, but on the home front. Thinking of Knitoscope’s calculation of knitted stitches into binary code to produce the final product, Mazza’s installation leaves much unknown to the viewer or rather, much is concealed in her work. Her work dissolves the sensation of the government’s aim of protection and safety through both the employment and distortion of the war images of Afghanistan, Iraq, Vietnam and World War II.

If, as Gilles Deleuze argues that “codes are passwords… indicating whether access to some information should be allowed or denied,” then what needs to be acknowledged outside of this established frame of coding?30 Haring and Mazza’s projects appear dependent on the viewer’s ability to decipher Morse code or on the historical frame that cultivated Knit for Defense: the video installation is altered to become less than documentary evidence and more of a visual anomaly as Haring’s sweater, to the untrained eye, is composed of simply knit yarn. Coding, warfare, and surveillance now incorporate the craft of knitting, but there is a system of knowledge that exists in each of these topics. If codes are passwords, then these digital and tactile iterations of knitted works are the information, but have evolved to combine their own historical connections to forms of espionage and binary coding. Through the use of a historically gendered medium, the tactile and technical interlocutions between textile and message only begin to tackle the histories surrounding women’s labour and knowledge. The very notions of coding, hacking, and even computer science more generally have been fields where women are marginalized; yet these artworks address the manner in which gendered spheres have traversed new boundaries into the sphere of digital information. But what exists outside of this established frame of coding? Haring and Mazza’s projects seem dependent on the viewer’s ability to decipher Morse code and on the historical frame in which the effort Knit for Defense arose. There is a lack of information provided to the viewer, specifically with Mazza’s work in which photographs become altered rather than part of a documentary action, or in Haring’s work where “SOS” functions as only a signal indicating distress rather than an acronym or abbreviation. Yet what makes Mazza’s work so compelling is how she manipulates the installation to incorporate photography—a medium with a long connection to the industrial war complex and surveillance. Despite the ever-evolving methods of information distribution, photography appeared at a time that witnessed a disharmonious industrialized society and yet evolved to become applicable to a range of technical and scientific progress within institutions. Therefore, photographs came to exist as a document of record, source of evidence, and witness. Tagg notes how this assumption of validity in the photographic assumed “a central and privileged place within its rhetoric of immediacy and truth…claiming only to ‘put the facts’ directly or vicariously, through the reports of ‘first hand experiences.’”31 Behind the knitted images, Mazza provides documentary evidence of war, often taken at face value. Rather than simply engage images from WWII, the artist traces the manner in which photography and later video footage had become incorporated into war surveillance; there is a connection to the very heroic storming of Normandy, the incredible airing of wartime footage from Vietnam, and the penultimate drone attacks that completely evacuate the human body from the frame of war.

Cat Mazza enacts a specific frame of war upon the viewer. Judith Butler’s Frames of War helps viewers understand just what has been provided to us by the artist. The various crafted items that are conglomerated under “knitivism” or “craftivism” actively highlight the government’s roles in nuclear attacks, militant invasion, and more generally, the industrial war complex of which has become so banal. Even the SOS sweater by Haring provides a connection to the craftivism that has evoked the ongoing scholarship over the past decade on the phenomenon. Mazza, however, encourages a much different approach to the critique of war. With Abu Ghraib and other tortuous events becoming staged for mass view, the frame of war seems clearly enmeshed with the act of photography, and in turn leaving specific questions on the role of representation and dissemination. Considering the dominance of embedded reporting that has allowed for an approved perspective from the US government and military, there is a difficulty according to Butler in how the viewer approaches these scenes of war. The viewer arrives at the image with the inability to process it outside the mandated “frame” of war—the scenes that Mazza portrays are both removed from the first frame in that they are approved images, caught in the legacy of these wars, and secondly, they exist as visual knits versus pixels.32 The visual and textual images read as signs of humanness or precariousness according to Butler, and, as such, the suffering of those in the degrading and humiliating photographs require recognition. Acts of recognition, such as the viewer’s visual realization in the knitted scenes, break and interrupt the grand narratives that surround war and represent victims.

As Sabrina Gschwandtner stated, “knitting is a living tradition—it’s physical knowledge of a culture. Knowledge of language dies so quickly. It’s awesome to find a sweater and look at the language of it—to see how it’s made, what yarn was used, and how problems were solved. A sweater is a form of consciousness.”33 Contemporary emphasis on knitting must be seen a political intervention as it makes these over sensationalized notions of war and mass media representation visible to the viewer. If one can gain a new point of entry to a longstanding and complicated debate, change can be possible. These connections to knitting, surveillance, coding, and warfare have become so entwined over the course of the 20th and 21st century. The double-entendre that appears with coding and the historical precedence that craft saw connected to espionage continue to exist, but have evolved to combine the technological advancements of binary coding and Internet hacking. However, interesting tension endures between the gendering of these spheres that artists, particularly those such as Kristen Haring and Cat Mazza, explore with their projects. The tactile and technical interlocutions between textile and message only begin to tackle the histories surrounding women’s labour and knowledge, and the manner in which these artworks have begun to delve into the typically gendered spheres has traversed new boundaries into the digital.

** I am indebted to Dr. John O’Brian and his seminar, “Photography, Surveillance, and Voyeurism” that provided the platform to analyze the politics of knitting. Many thanks to Cat Mazza, Kristen Haring, Sabrina Gschwandtner, and Dr. Trish Kelly.

- Nicholas R. Bell, “Craft Futures: A Generation at Hand,” in 40 Under 40: Craft Futures, (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian American Art Museum, 2012): 22. ↩

- Ibid., 21. ↩

- Betsy Greer, “Craftivist History,” in Extra/Ordinary: Craft and Contemporary Art, ed. Maria Elena Buszek, (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2011): 178. ↩

- Robertson, “Rebellious Doilies and Subversive Stitches: Writing a Craftivist History,” in Extra/Ordinary: Craft and Contemporary Art, ed. Maria Elena Buszek (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2011), 189. ↩

- Ibid., 192. ↩

- Ibid.,196. ↩

- Karl Marx, “From the Minutes of the General Council Meeting of July 28, 1868,” On the Consequences of using Machinery under Capitalism. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/iwma/documents/1868/machinery-speech.htm ↩

- Sadie Plant, “Binaries,” in Zeroes and Ones: Digital Women and the New Technoculture (London: Fourth Estate, 1997), 32-33. ↩

- Julia Bryan-Wilson, “Knit Dissent,” in Contemporary Art: 1989 to the Present, ed. Alexander Dumbadze and Suzanne Hudson (Sussex: Wiley Blackwell, 2013), 245. ↩

- On the program, Knitoscope, Mazza explains: I work with a custom program called Knitoscope to create animations. The program is based on the open-source freeware and knit pattern program knitPro that’s hosted on my website microRevolt.org. Knitoscope builds on the concept of image to stitch but is an application for moving images. Knitoscope builds on knitPro’s concept of image to stitch but is an application for moving images. I developed it in 2005 as a grad student and it was programmed in C with Quicktime and OpenGL by Shawn Lawson. Basically I hand- or machine-knit a swatch, scan individual stitches into a database and then the program will generate a stitch in correlation to the video’s RGB. The final video is threaded together with multiple programs based on source footage from World War II, the Vietnam War and wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.” Jenny Gill and Cat Mazza, “In Focus: Cat Mazza’s “Knit for Defense,” Creative Capital: The Lab, 16 July 2012, http://blog.creative-capital.org/2012/07/in-focus-cat-mazzas-knit-for-defense/. ↩

- Bryan-Wilson, “Knit Dissent,” 247. ↩

- John Tagg, The Disciplinary Frame: Photographic Truths and the Capture of Meaning (Minneapolis and London: Minneapolis University Press, 2009), 3. ↩

- Paul Virilio, “Travelling Shot over Eighty Years” in War and Cinema: The Logistics of Perception (London and New York: Verso, 1989), 79. ↩

- Bryan-Wilson, “Knit Dissent,” 247. ↩

- Lucy Adlington, “Knitting by the Ton” in Great War Fashion: Tales from the History Wardrobe (Gloucestershire: The History Press, 2013), 109-11. ↩

- Gilles Deleuze, “Postscript on Control Societies” in CTRL (SPACE): Rhetorics of Surveillance from Bentham to Big Brother, ed. Thomas Y. Levin, Ursula Frome, and Peter Weibel (Karlsruhe: ZKM Center for Art and Media, 2002), 318. ↩

- This argument concerning domestic labour has been addressed in multiple places; however, because of the scope of this paper, there is both a need to highlight this seen/unseen-gendered labour. Helen Molesworth’s, “House Work and Art Work,” October 92 (Spring 2000), 71-97. ↩

- Paula Becker, “Knitting for Victory—World War II,” HistoryLink.Org. 19 August 2004. http://www.historylink.org/index.cfm?DisplayPage=output.cfm&File_Id=5722 ↩

- Bryan-Wilson, “Knit Dissent,” 247. ↩

- “Suddenly women were wanted again – for long, long hours and derisory wages. Khaki fabric was tough to sew, rough on the hands and hard for the eyes.” Adlington, “Knitting by the Ton,” 104. ↩

- Ibid., 109. ↩

- Ibid., 111. ↩

- Ibid., 109. ↩

- Molly Oldfield and John Mitchinson, “QI: How Knitting was Used as Code in WW2?” The Telegraph, February 18, 2014, accessed February 19, 2014. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/men/the-filter/qi/10638792/QI-how-knitting-was-used-as-code-in-WW2.html ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- BBC Radio 4, “MI6: A Century in the Shadows,” July 27, 2009, accessed April 3, 2014. http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00lrsnk ↩

- Oldfield, “QI: How Knitting…” ↩

- Transmission Arts: Artist Experiments with Broadcast Media and the Airwaves, “Kristen Haring,” accessed April 3, 2014. http://transmissionarts.org/artist/pfsbgd ↩

- Spark 172 with Nora Young, “The Beauty of the Binary,” February 12 &15, 2012, accessed on April 3, 2014, http://www.cbc.ca/spark/episodes/2012/02/10/spark-172-february-12-15-2012/ ↩

- Deleuze, “Postscript,” 319. ↩

- John Tagg, The Burden of Representation, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993), 8. ↩

- Judith Butler, Frames of War: When is Life Grievable. London: Verso Books, 2009: Butler’s argument revolves around how the viewer arrives at the image with the ability to process it outside of the “frame” of humanity and can thus negate a “haunting;” she, therefore, disavows Susan Sontag’s argument that the narrative informs and the image haunts. When the subject is seen outside of the frame of humanity, the images are no longer haunting—without this sense of haunting, there is no sense of loss and the individuals are not seen as grievable because they are outside the frame that the viewer considers human. ↩

- Gschwandtner, “Knitting is…” 275. ↩