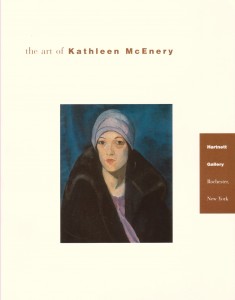

This essay returns me to Rochester, thirteen years after I left. It also returns me to a mild obsession I developed in my last year in Rochester with the artist Kathleen McEnery Cunningham, and with the fascinating social and cultural world of Rochester in the 1920s. I curated an exhibition of McEnery’s work at the Hartnett Gallery at the University of Rochester in 2003, and advised on another in New York a couple of years later. The essay will also be a chapter of a book I am completing, entitled Austerity Baby, which is part memoir, part family history, part cultural history. Two other chapters were published in 2013: one in the collection Writing Otherwise (edited by Jackie Stacey and Janet Wolff, published by Manchester University Press), and another here in the online literary journal, The Manchester Review.

* * *

The American artist Kathleen McEnery Cunningham presided at the center of a lively cultural scene in Rochester, New York, in the 1920s and 30s. In 1914, she had married Francis Cunningham, then secretary and general manager of James Cunningham, Son and Company, a luxury coach- and car-making company. She was probably introduced to Cunningham by his cousin, Rufus Dryer, a good friend of hers in New York and, like her, an artist and a student of Robert Henri at the Art Students League a few years earlier. Before her marriage she lived in New York, where she was already achieving success as a young artist. Her paintings were exhibited in gallery shows in the city with the work of Stuart Davis, Edward Hopper, George Bellows and other now well-known artists, and two were included in the landmark 1913 Armory Show, known as the major exhibition which introduced European modernism to the United States. In Rochester, she continued to paint—mainly still life works and portraits of her friends and acquaintances.

The city was transformed in the years immediately after McEnery’s arrival. Living in Rochester myself for the last decade of the twentieth century, I eventually discovered the city’s fascinating history, which I wrote about in another context:

Economically, the first three decades of the twentieth century had been described as Rochester’s golden age, and the centrality of Eastman-Kodak to the city’s prosperity had important cultural consequences. The establishment by George Eastman of the Eastman School of Music and the Eastman Theatre in 1922 was the single most important event marking the “end of provincialism.” Eastman brought musicians, opera directors, and teachers to Rochester from the capitals of Europe and thus virtually single-handedly created the conditions for a new cosmopolitanism in the city . . . A lively social and cultural world developed around this group, and McEnery (now Mrs. Francis Cunningham) was central to it.

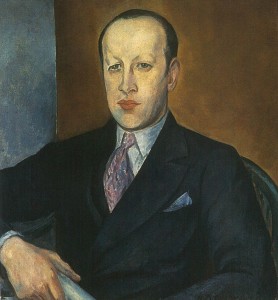

As a result of a series of chance events, I spent my last year in Rochester (2000-2001) doing research on McEnery’s work and life, interviewing people who remembered her (she died in 1971), and getting to know many of her twenty grandchildren. Of her three children, only Peter Cunningham was still alive, living in northern California. (He died in 2003, soon after the close of an exhibition of McEnery’s work I had curated in Rochester, which he was too ill to attend.) I met him a number of times, in Sausalito, San Francisco, and New York, and got some of my best information (and gossip) from him—to be treated cautiously, according to some of his children. Peter Cunningham’s account of McEnery’s involvement with the English orchestra conductor Eugene Goossens (brought to Rochester by George Eastman in the 1920s) seems to have been common knowledge, though. McEnery painted Goossens’s portrait at least twice; one portrait is still in the Eastman School of Music.

Several of the people I spoke to—mainly women in their 80s and 90s—remembered McEnery well, especially in her later years, and had fascinating stories to tell about the salon she ran in her house on Goodman Street (bequeathed to the Rochester Museum and Science Center on her death, and now used as the Center’s administrative offices). Belatedly, I came to realize what a fabulous world Rochester must have been in the 1920s (prohibition notwithstanding—indeed, from everything I heard, it was more or less ignored). The gorgeous villas on East Avenue and nearby (including Eastman’s own home, now the George Eastman International Museum of Photography and Film) stand as a reminder of a way of life for the city’s wealthier inhabitants.

* * *

Rochester in the 1920s is vividly portrayed in Paul Horgan’s charming roman à clef, The Fault of Angels. The novel was published in 1933, and won the Harper Prize of 1934. Horgan, who died in 1995, is best known for his fiction and non-fiction writing about the American Southwest, winning the Pulitzer Prize for History in 1955 and 1976 for two of his books. He was born in Buffalo, New York in 1903, and moved with his family to Albuquerque at the age of twelve. After high school in the New Mexico Military Institute, he moved to Rochester as a music student in the new Eastman School of Music, and spent the years 1923 to 1926 in the city, before returning to New Mexico to become the librarian of the Military Institute. As he tells the story, at the age of nineteen he found himself involved in multiple tasks in the new music school and opera company, working with George Eastman’s protégé, Vladimir Rosing, a Russian tenor brought to Rochester as director of the school’s opera department; and with Rouben Mamoulian, hired in turn by Rosing to teach dramatic action. Horgan’s account of his own role, written in 1988 in an appreciation of Mamoulian, gives an idea of the excitement, and also of the rather chaotic nature, of the early years of the “Rochester Renaissance”—a renaissance almost entirely due to the wealth and cultural enterprise of the city’s major figure, George Eastman:

The exciting days of the convening of the company were bounteous with promises for the future. Rosing made an address to the school of music at large in Kilbourn Hall, describing the aims of the company and its policies. As a newly enrolled music student, I was in that audience, listening with the same excitement as the members of the company. In all his plans, Rosing mentioned nothing about scenery, an art director, the physical mounting of the operas about to be undertaken. I needed a job to see me through my study of music. I produced overnight a sheaf of drawings for various operas I knew, and took them to him the next day. My authority for this bumptious venture was based wholly on my having planned and painted the scenery for two plays, a year or two before in school. After several hilarious incidents having to do more with me than with Rosing or Mamoulian, but within forty-eight hours, I was engaged to do the designs and paint the scenery for the opera company….. I was then nineteen years old, an unpublished writer, an unexhibited painter, an unheard singer, an unseen actor, and, above all, an unrevealed scenic artist.

In the opera company’s second season, Horgan was, he says, “relieved of my assignment as scenic artist, and a professionally experienced artist brought in.” But the careless mix of amateur and professional involvement—as it now seems to us—continued:

My duties became more various. In effect, I was Mamoulian’s Figaro, his general assistant, responsible for any number of details of the productions. At the same time, I was supposed to think up and even write the stage acts for the movie house each week. In a few of them I appeared myself. The job was fascinating, if exhausting. I had an intensive apprenticeship in production, design, acting, singing, writing, musical selection—the blend of the arts that go to make up the vocabulary of the stage. I remember that I was charged with designing make-ups for the productions of the operas, and every time we gave one, it was I who, with Mamoulian himself, “did” all the major people in their characters, applying grease paint up to the very minute of the curtain.

(The reference to the “movie house” recalls that the Eastman Theater in its early years was used six nights a week for movies, and the seventh for concerts.)

Horgan developed a close friendship in these years with the composer Nicolas Slonimsky, who also came to Rochester in 1923 as opera coach of the new company. In his amusing—and grandiose—autobiography, Slonimsky (who calls Horgan his “hagiographer”) describes him as a “kindred soul,” and a “talented painter and illustrator” who also “wrote facile verse and clever short stories.” In The Fault of Angels, Slonimsky is a central character, with the fictional name “Nicolai Savinsky” (or “Colya”), a close friend of the protagonist, “John O’Shaughnessy.” (Horgan’s own heritage was German and Irish.) The George Eastman character is easily recognizable in “Henry Ganson,” the multi-millionaire who had already given the university of the city of “Dorchester” a medical school, a dental school, a museum and a library—and now a theater and music school. The conductor Eugene Goossens (mentioned earlier in relation to the artist Kathleen McEnery), who was engaged by Eastman in 1923 and stayed in Rochester until 1931, is most likely the fictional conductor “Hubert Regis.” Indeed, in a letter of January 26, 1934, written from New Mexico to Kathleen McEnery in Rochester, Paul Horgan says this:

I had a most lively and amusing letter from Gene about my book. He said he was amused, and much surprised that I’d taken no more cracks at him than I did!

The novel re-creates this social and cultural world, centered on the music school and opera company, and convening in the Corner Club (called by its real name in the novel) for drinks and meals before and after concerts. There doesn’t seem to be a McEnery character, but another of the city’s salonnières, Charlotte Whitney Allen, has much in common with “Blanche Badger,” whose book-lined home is always open to her friends. McEnery painted Charlotte Whitney Allen’s portrait a number of times; my favorite of these paintings is now in the Rochester Institute of Technology.

* * *

The star of the novel, though, is Nina. A White Russian arrived from Paris in 1924, she is the wife of “Vladimir Arenkoff” (“Val”), whom the protagonist, John, befriends. Nina is a passionate, flamboyant, and beautiful woman, with artistic abilities (or perhaps pretensions). She makes an overwhelming impression on John at their first meeting, and he remains charmed by her, and in love with her, until she and her husband leave for good the following year:

She stared at the gray bare trees outside, whose branches leaned upon the bay window in her turret alcove. She was not tall, but her body was so exquisitely shaped that she gave an impressive hint of tallness. Her face was really oval, pointed at the chin. Her brow and cheeks were pale with underglows of pearly café au lait. Her eyes were deep and sad and black, with sparkling whites and definitely curving brows that gave a frank mystery to her countenance. Her mouth was small and inconceivably expressive, even in repose. She had rouged it only at its outline. Her neck was magnificent, slender and full and straight. No jewel diluted its loveliness. Her shoulders went from it with the pride of waves. She was wearing a gown whose chic made the women in Dorchester look dowdy and content to be so. Her hands had long nails and no jewels. This morning she was holding in them a gold comb.

Almost immediately, John has a glimpse of how intensely she experiences every event, and how dramatically she inhabits the world:

“I do hope you will find it pleasant here,” said John, speaking a little slowly and a little loudly, until he realized that she was not deaf, but only unfamiliar with English. “Oh, mon Dieu!” she said, and with the greatest dignity began to weep. Her eyes were more brilliant, if anything, behind her tears, and John’s astonishment disappeared in admiration of her sadness and its great loveliness.

There is much more weeping, and there are many dramas, in the novel, by the end of which John succeeds in overcoming his crush on this lovely woman, who has spent a good deal of energy in trying her best to improve the lives of several people in the city, sometimes with success, often (most notably in the case of “Ganson” himself) without.

I had assumed that “Nina” was entirely an invention of the author’s, or, perhaps, a composite of several of the Russians brought to Rochester by Eastman and Rosing. But when I read Horgan’s letter to McEnery—the one in which he mentions the letter from Goossens—I realized that not only was she based on a real person, but “Nina” was her real name:

Dear Kathleen,

It was so delightful of you to send me the Nina letter in such a nice letter of your own that I am ashamed to answer you this lately for both. The Ninaisme is so really like that I am possessed of the curious conviction that my character in the novel was at times clairvoyant. I only wish it could be savoured by the reviewers who felt I’d poured it on too thickly…that no one could possibly think and talk/write like that. Of course, if only I could have invented such a line as the one in the letter: ‘Life is short and life is once’: I’d feel that the Harper prize was deserved this year. As it is, I have many doubts as to that.

Do you know, I am very curious to know what (if anything) E.B. thought of the book: and Nina herself, if she’s seen it. I sent them a copy long ago in the summertime, care of the Eastman School. But I have heard nothing from them. I am grieved to think I may have offended either of them with the story. Can you tell me anything? Oh, if they felt mockery in it anywhere, I should be awfully sorry. Because it isn’t there. Yet I take their silence to mean pique. I hope I’m wrong. Surely they perceive the problem of fiction: the taking of a model and the evolvement of something altogether personal and invented…fictional…from it? I really meant it when I put the ‘usual’ fiction disclaimer on the reverse of the title page. But no one ever believes that.

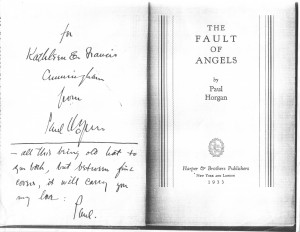

Horgan had also given a copy of the book to McEnery and her husband, inscribed inside: “for Kathleen & Francis Cunningham from Paul Horgan—all this being old hat to you both, but between fine covers, it will carry you my love: Paul.”

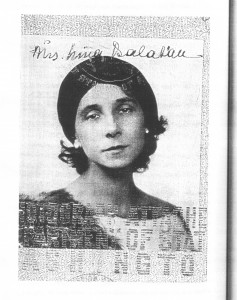

So who was Nina, and who was “E.B.”? If he had sent one copy for the two of them, it seems likely that E.B. was Nina’s husband. My assumption is that he was Emanuel Balaban, a conductor of the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra (a position he shared with Eugene Goossens in the 1920s). Balaban’s wife was indeed called Nina. Horgan’s letter to McEnery ends by asking her to send him a photograph of “the Nina portrait”—“the first one you did . . . In the gold dress, with the lucent and lunar hip.” In my research on McEnery, though I was able to see well over a hundred of her paintings (including one of another beautiful Russian woman, Katya Leventon, wife of a violinist in the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra), I hadn’t come across a portrait of this description. Having made the guess that she was the model for the fictional Nina, though, I then discovered Bruce Kellner’s 2002 literary portrait of Nina Balaban, whom he knew in New York in the 1950s. A graduate student in the University of Iowa’s writing program at the time, he decided to spend the summer of 1956 in New York, sharing an apartment with a friend from Iowa’s theater department. They came to rent Nina Balaban’s fifth-floor apartment at 6 West 75th Street for $65 a month, while she summered, and painted, in Woodstock. Here is a Nina thirty years after Horgan’s character:

Nina was in the doorway, managing to look apprehensive, welcoming, imperious, and charming all at the same time. Her eyes struck me first, dancing gray eyes, straight across the bottom and rounded into half-circles, black-rimmed and batting mascara-heavy lashes at us, under mismatched arcs for eyebrows, drawn on in high, single lines. Her teeth were white and even, and her hair was a reddish nest through which an electric charge might have recently surged. She was nut-brown, like soft and weathered leather. At first she seemed to be no taller than five feet, gaunt and wizened, and then perhaps of medium height and as youthful as we were. Was she forty? Sixty? I couldn’t tell. She wore huraches (sic) on her bare feet and an oversized blue wrapper, and under it a plain, soft blouse and a fulsome peasant skirt. There were gypsy loops with little rocks hanging from them in her earlobes; necklaces of beads, seeds, pods, semi-precious stones dangling from her neck; bangles on her wrists. The bright crimson staining her lips bled into tiny lines around them.

Older, of course. But also much changed from the unadorned goddess of Horgan’s description. (And now “nut-brown,” no longer “pale, with underglows of café au lait.”) One can allow for changing styles, for the pressures on an older woman, perhaps for the new milieu of the Woodstock art community where Nina spent her summers—and, of course, for fiction. Still, Kellner abolishes any doubt about the real and the fictional Nina. In one of her letters to him, after that first summer (he sub-leased her apartment again the following summer), she asks him, in her idiosyncratic spelling, if he knew where her copy of The Fault of Angels was:

I can’t find a book – “Fault of Angels” by Paul Horgan – This book is very dear to me – it was written about me and by my friend Paul – It is so important to me to have it. Did you tack it?’

The following summer, Kellner found the book for her, in her hall closet. But here is something very interesting—and, to me, rather mystifying. While the book was still missing, Kellner offered to try to find a second-hand copy for her:

No, she said, smiling and crying at the same time, another copy would not be the same thing; it was that particular copy that meant so much to her because she and Horgan had been lovers, and every time they’d gone to bed together they’d made a hole with a thumbtack in the binding.

When Kellner asked her about Horgan, she said “not sadly but wistfully perhaps, ‘we do not see each ozzer any more longer.’”

But could this possibly be true? The love affair in the novel is clearly unconsummated, and just as clearly one-sided. Nina is devoted to “Val,” her husband. Of course it’s fiction. But it seems very unlikely that the real “John,” Horgan himself, was actually involved with Nina. Moreover, if they made a hole in the binding each time they went to bed together (itself a rather weird-sounding ritual—but who knows?), then it must have been after the book’s publication in 1933. By that time, Horgan had long been in Albuquerque, and Nina in New York. (According to Kellner, “Maestro Balaban had long departed from Nina’s life when I knew her.”) Whatever the truth about this affair (and personally I suspect that Nina’s wild imagination created it in retrospect), I do wonder whether Horgan’s mind was ever put at rest on the question of Nina’s, and E.B.’s, reaction to reading the novel.

Although I haven’t been able to trace the portrait of Nina described by Paul Horgan, there is a Nina portrait by Kathleen McEnery, owned by one of the artist’s grandchildren; this is reproduced on the cover of the exhibition catalogue from 2003. Another portrait, though not identified, is very likely another of Nina. A comparison with a photograph in Kellner’s book is fairly convincing.

* * *

The “Rochester Renaissance” owed a lot, as I have said, to Eastman’s wealth and philanthropy. The city of the 1920s is often referred to as “Mr. Eastman’s town.” Amongst other achievements, he brought Martha Graham, then at the beginning of her career, to teach dance movement in the opera company in 1925. But other wealthy denizens of the city participated in the transformation of a quiet provincial city into an exciting cultural center. Emily Sibley Watson, heir to the Western Union fortune (both through her father, Hiram Sibley, and through her second husband, James Sibley Watson), had founded the city’s Memorial Art Gallery in 1913 in memory of her son James Averell, who died of cholera in 1904, at the age of twenty-six. The son of her second marriage, James Sibley Watson Jr., doctor, publisher, avant-garde film-maker, who died in 1982, spent most of his life in Rochester, after studies at Harvard, a short residency in Chicago, and a number of years in New York, where he pursued his medical studies at New York University. In 1919 he took over, with Scofield Thayer, the publication and editing of the respected New York-based literary journal The Dial. The journal ceased publication in 1929, but it had produced life-long friendships for Watson (known to everyone as Sibley) and his wife, Hildegarde Lasell. The poet Marianne Moore, who took over the editorship of the journal in its last years, visited them in Rochester, and had a lengthy correspondence with Hildegarde. (Volume 85 of The Dial, from 1928 contains two paintings by Kathleen McEnery, probably thanks to Hildegarde’s role, described in her memoir, of finding artists to include.)

On his return to Rochester in the late 1920s, Watson became involved in making movies, and with Melville Webber produced two films generally regarded as classics of the avant-garde—The Fall of the House of Usher (1928) and Lot in Sodom (1933). (In later years, he went back to his career in medicine, working in the University of Rochester’s radiology program, where he helped invent cinefluorography—X-ray motion pictures—which became an important diagnostic process.) Hildegarde, who had been an actress and singer in her early years—and had first met Sibley when she performed in something called Betsey Abroad, with, amongst others, Charlotte Whitney (soon to be Mrs. Atkinson Allen), in 1912—played Madeline Usher in the first film, and Lot’s wife in the second. The architect Herbert Stern, brought in to play the part of Madeline’s brother Roderick, looked back at the experience in 1975:

Every time I see the Watson-Webber version of The Fall of the House of Usher I am struck anew with wonder and awe. How was Dr. Watson, almost fifty years ago, able to produce a film that is, technically, avant-garde today? I had a part in the film, but all of the trick photography was done behind my back, as it were, and I had no idea that I was taking part in an epoch-making film. Perhaps there were props, but I can’t seem to remember them…

I have often wondered why I was chosen for the part. Could it be that Sibley thought of Roderick as a robot and sensed that I might fulfill that role? I took directions from Melville Webber and they were mystifying in the extreme: “Look weary and at the same time jubilant.” “Look perplexed and at the same time relaxed.” It was easy to appear weary and perplexed but never for a moment relaxed and jubilant.

The composer, Alec Wilder, who wrote the score for that film, recalls his involvement in Lot in Sodom a couple of years later. Another composer wrote the music, but Wilder, who was studying at the Eastman School of Music, helped to find the supporting cast:

The Sodomites themselves were a bit of a problem for, as is obvious, considering their sexual aberrations, they would be more convincing as Sodomites not only if they were lavishly costumed, but if their physical movements were on the effeminate side.

So I did a perhaps mean thing: I approached the most effeminate among the Eastman School students and, under some wildly false pretense, persuaded them to come to the “barn” for a tryout. Unsuspecting of my nefarious plot, they arrived like swallows returning to Capistrano, allowed themselves to be lavishly bedecked and alarmingly maquillaged by Melville Webber, with the great wit and hyperbole that were his special talent… and permitted themselves to be photographed in a hysterical, posturing group. But it must have rapidly become clear that their unconventional personalities were being mocked, for they never appeared again. I’m surprised that I had the courage to enter the Eastman School during their subsequent (admittedly justifiable) fury at having been so misled.

In 2001, I interviewed Nancy Watson Dean, who had married James Sibley Watson after Hildegarde’s death in 1976. She left her own first husband, to whom she had been married for forty years, to marry Watson, after a long friendship with him and with Hildegarde. After Watson’s death, she was married a third time, to a childhood friend, Sterling Dean, in a marriage that lasted fifteen years, until his death in 2000. In preparation for our first meeting, she wrote a five-page memoir, which she read aloud to me when I visited her in January 2001. She spoke about Sibley’s involvement with The Dial, and about her own early career as a watercolor portraitist of children. She recalled Kathleen McEnery, and had known her children, Joan and Peter, quite well at one time:

During Hildegarde’s heyday, she and 2 other wealthy matrons here entertained often and loosely organized a real coterie. The other 2 matrons were Clayla Ward and Kathleen Cunningham. The scene, in this distinctly conventional city, consisted of several gays (though nothing was said about that), several couples and a number of attractive widows. They met at various locations and were unconventional and merry…

Concerts were held every week, and before long I discovered that during intermissions, if you went to a certain hall on the Gibbs St. side of Eastman theater, Kathleen and Clayla, and often Hildegarde, held court. It was an interestingly dressed, chic crowd. After the concert, it often re-met either at Clayla’s, which was a mansion on Grove St. or a restaurant called “Town & Country” on Gibbs St. across from Eastman Music School…. Another place they gathered was the Corner Club. This was up a flight of stairs in a building just east of the present Carlson Y. The same chic dressers, much gaiety…All three of the reigning women were witty, amusing and loved their devotees. They knew the latest “happenings” in Rochester and conversations were interesting.

Although I had the chance to talk to other elderly women who remembered Kathleen McEnery, and recalled something of the Rochester of a certain class and cultural circle, I came too late to be able to encounter many recollections of “the golden age.” Elizabeth Holahan, ninety-seven years old when I interviewed her in 2002, two years before her death, was long-time President of Rochester Historical Society and life-long resident of Rochester. She had worked all her life as a house restorer, amongst other things restoring the house of Eastman’s birth in Waterville, NY, and having it moved to the Genesee County Museum. She remembered all the grandes dames of an earlier Rochester, but kept her distance, telling me that, unlike them, she had to work for a living. At some point in our conversation, she went down to her basement, and returned with two small portraits done by Kathleen McEnery—one of her sister, Margaret, who had died young, and one of herself. (These are now in the Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester.) She told me that she didn’t at all want to sit for the portrait—that she was too busy at work—but that Kathleen “wouldn’t take no for an answer.” My conversation with her reminded me that my view of 1920s Rochester was very skewed, to an upper-middle-class and rather privileged sector of the community. But it remains quite fascinating to me. And Miss Holahan (as she was known) was probably my closest connection to that world. As the Executive Director of the Rochester Historical Society, Ann Salter, said when she died, this was “an incredible passing for our community.”

I was struck by the extraordinary change in life she witnessed—her life spanned a century,” Salter said. “She’d talk about a party at the George Eastman House, and then it would hit me: George was actually there.

George Eastman died on the 14th of March, 1932, at the age of 77. He had been in failing health for some time. After a busy morning of meetings and document-signing at his home, he lay down on his bed and shot himself in the heart. He left a note beside the bed: “To my friends. My work is done—Why wait? GE.”

* * *

Before I “discovered” Kathleen McEnery in 1995, she had had a brief moment of visibility in 1987. This was the year the National Museum of Women in the Arts opened in Washington, D.C. Two of McEnery’s paintings were included in the inaugural show, curated by Eleanor Tufts. She writes this in the catalogue:

Kathleen McEnery is one of the discoveries of this exhibition. A whole corpus of impressive works exists in the homes of her children as testament to her painterly accomplishment. Two of her paintings were in the Armory Show of 1913, and her works were exhibited in New York galleries. But after this promising beginning, she yielded to her responsibilities as wife and mother and gave up her artistic commitment.

In 1914 her marriage to Francis E. Cunningham took her to Rochester, New York, where he manufactured in his grandfather’s carriage factory the Cunningham automobile, “the nearest thing to a Rolls-Royce produced in America.” They had a daughter and two sons in the first decade of their marriage, and in 1917 the family moved to a new house, which included a spacious studio.

The two paintings Tufts included in the 1987 show were Going to the Bath (one of the works included in the Armory Show, and now in the National American Art Museum in Washington, D.C.) and Breakfast Still Life (owned by McEnery’s granddaughter in Virginia, and the painting I chose for the front cover of my book, AngloModern). Eleanor Tufts is wrong about McEnery giving up her art after marriage. (Indeed, an article about her in the Rochester local paper in the 1930s is headed “Mrs. Cunningham: Real Artist and Real Wife and Mother.”) It’s a little surprising that she was left with this impression, since she was in contact with McEnery’s son Peter (by correspondence) and daughter Joan (also by correspondence, and a visit to Joan’s home in November 1985). Joan Cunningham Williams, who was married to a diplomat and at that time lived on a farm in Virginia, was herself an artist. She studied in New York and Paris, and was commissioned as a WPA artist in 1940, when she painted a mural at Poteau Post Office in Oklahoma. (She wasn’t necessarily Eleanor Tufts’s most helpful informant, though. In one of her short hand-written notes to Tufts, she has five mistakes about her mother, included date and place of birth and date of death. She also seems to have forgotten, as Tufts politely points out in her reply to another letter, to have included a promised map for Tufts’s visit to the farm.)

I was able to see Eleanor Tufts’s papers, including the correspondence with the Cunninghams about McEnery’s work, thanks to her colleague at SMU, Alessandra Comini, herself a distinguished art historian who has written widely on early twentieth-century German and Austrian art. In her letter to Joan Cunningham Williams (reminding her to send the map), Eleanor Tufts adds a postscript to say, “One or two colleagues may drive with me.” Alessandra Comini did accompany her, as Tufts’s later letter of thanks makes clear:

Dear Mr. and Mrs. Williams,

You were absolutely wonderful about showing us the paintings of Kathleen McEnery, and I deeply apologize about our driver’s wrenching us away prematurely. Both Professor Comini and I felt very privileged to meet you both, and we reluctantly departed at the insistence of our hostess…

Both Alessandra and I hope that we might some day return to visit you – next time in a rented car!

As far as I know, they didn’t visit Joan Williams again, though the correspondence continued for several months as the NMWA show was planned (and as Eleanor Tufts changed her mind several times about which works by McEnery she wanted to borrow). After her discovery of the artist on this occasion, Tufts included a note about her in the 1989 edition of American Women Artists, and contributed a short piece about her for Jules Heller and Nancy G. Heller’s North American Women Artists of the Twentieth Century; the 1995 edition of the latter book is dedicated to Eleanor Tufts after her death in 1991.

* * *

Nina Balaban left New York some time after Kellner’s acquaintance with her in the 1950s. Born in 1890, she lived to be one hundred and one, and died in 1991. I contacted Bruce Kellner in February 2006, before I left the United States to return to England after a stay of eighteen years. Not very surprisingly, he still remembered her well. He put me in touch with the artist Sam Spanier, who lived in an arts community and spiritual center called Matagiri , near Woodstock, which he had founded with his partner Eric Hughes in 1968. We exchanged letters, and had a long telephone conversation that same February (Spanier died in 2008) . He knew Nina Balaban throughout the later decades of her long life—he recalled meeting her on a beach in Provincetown in the 1940s, when, by then in her 50s, she was in a bikini and, according to him, looking many years younger than her age. He recalled that she lived for many years with a sculptor, more than twenty years younger than herself. Ten years after Sam Spanier’s first meeting with Nina, when Bruce Kellner rented her New York apartment, he couldn’t tell if she was forty or sixty. She told Kellner, in 1956, that she wanted to go to Woodstock for the summer to paint. They continued this rental arrangement for two more summers.

Nina moved to Woodstock permanently in the early 1960s. Already established as an artist, she began to specialize in hand-painted ceramic plates. These still turn up from time to time on auction websites. Today—the day I am writing—I find on Amazon a book of her printed covers (at £124 rather too much of an extravagance for me to send for):

Balaban, Nina. Plan zemli. (Russian Edition) New York, National Printing & Publishing Company, (1936). 4°. 40 pages. Original printed wrappers with art-deco illustration. The front cover with a small tear and chip. A little dusty. Inscribed by Nina Balaban to Kathleen Cunningham To my dear friend Cathleen – with love from Nina. 5.Feb.36 New York. With the printed dedication for Emanuel Balaban. Text in Russian.

Kathleen Cunningham is, of course, Kathleen McEnery, under her married name.

* * *

With thanks to the Cunningham and Williams families for images, information and encouragement; to Bruce Kellner and the late Sam Spanier for conversations about Nina Balaban; to Professor Alessandra Comini for allowing me access to Eleanor Tufts’s correspondence; and to Margaret Beetham, Brenda Cooper, Viv Gardner and Judy Kendall for helpful feedback on this essay.

Image credits

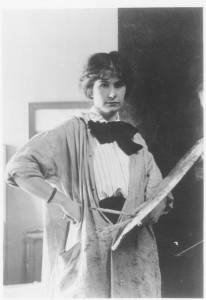

Photograph of Kathleen McEnery, c. 1910, photographer unknown. Image provided by the Cunningham and Williams families.

Exhibition catalogue, The Art of Kathleen McEnery, 2003. Hartnett Gallery, Rochester, NY.

Kathleen McEnery, Portrait of Eugene Goossens, c.1927. Image provided by The Sibley Music Library, Eastman School of Music, University of Rochester, and with the permission of the Cunningham and Williams families.

Photograph of Cunningham residence, photographer unknown. Image provided by the Cunningham and Williams families.

Photograph of Cunningham residence, 2001, by Janet Wolff.

Kathleen McEnery, Woman Seated (Charlotte Whitney Allen), n.d. Image provided by Rochester Institute of Technology.

Frontispiece of The Fault of Angels by Paul Horgan, with inscription, 1933. Photograph by Janet Wolff.

Kathleen McEnery, Portrait of Nina Balaban, n.d. Image provided by Anne Subercaseaux, San Francisco.

Photograph of Nina Balaban, 1925, photographer unknown.

Works cited

Paul Horgan, The Fault of Angels (New York and London: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1933).

Paul Horgan, “Rouben Mamoulian in the Rochester Renaissance,” in A Certain Climate: Essays in History, Arts, and Letters (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 1988), 195-220.

Corydon Ireland, “Elizabeth Holahan, a lifelong friend to city, dies,” Democrat and Chronicle (December 29, 2002), 3B-4B.

Bruce Kellner, “Nina Balaban,” in Kiss Me Again: An Invitation to a Group of Noble Dames (New York: Turtle Point Press, 2002), 209-228.

Herbert Stern, “Some retrospective views (II)” in “The films of J.S. Watson, Jr., and Melville Webber”, The University of Rochester Library Bulletin, Vol. XXVIII, No.2 (Winter 1975): 77-78.

Eleanor Tufts, Catalogue entry on Kathleen McEnery Cunningham, in American Women Artists 1830-1930, ed. Eleanor Tufts (Washington, D.C.: The National Museum of Women in the Arts, 1987), 55.

Alec Wilder, “Some retrospective views (III)” in “The films of J.S.Watson, Jr., and Melville Webber”, The University of Rochester Library Bulletin, Vol. XXVIII, No.2 (Winter 1975): 79-85.

Janet Wolff, “Questions of discovery: the art of Kathleen McEnery,” in AngloModern: Painting and Modernity in Britain and the United States (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2003), 41-67.

1 Comment