Christopher Schaberg and Timothy Welsh

Picture an everyday traveler’s experience at the airport: the traveler checks in and receives a boarding pass, consults a monitor for the flight’s status, queues through security, waits, boards, and finally reposes in the aircraft seat, perhaps thumbing over an iPhone’s screen as the engines purr to life. In this situation, interactions between the individual traveler and the larger airport network are abound: humans, machines big and small, information technologies, a vast grid of energy, politics, geography. The reality of air travel exists on many levels at once, crisscrossing lines of human phenomenology, computer data flows, and physical logistics.

Walking into an airport in a videogame happens somewhat differently, yet with curious similarities. After entering a disc into the terminal, the player logs on, checks game settings, and waits through load screens. The console meanwhile processes a queue of commands and inputs, pixels rapidly changing color to depict free-motion through virtual space as the player sits back, thumbing a controller as the CPU fan purrs in the background. A simulated space skinned to resemble an airport at last materializes on the screen, and game play can commence.

These two distinct contexts—the airport and the airport-in-videogame—clearly overlap thematically and share strange haptic experiences. As we play through the terminal over the course of this essay, we will see how these overlaps are more than thematic, and the somatic similarities far from simple. Numerous videogames employ airport levels as spaces for action and pursuit. The 3D renderings of their familiar environs offer a plentitude of “ordinary affects”1 and behind-the-scenes details as fodder for pursuit and evasion. Concurrent with advances in gaming technologies have been advances in the digital technologies supporting air travel, particularly handheld devices. Not only have airlines upgraded digital systems to enhance efficiency and the in-flight experience, travelers carry more and more powerful digital devices—laptops, tablets, phones, mobile gaming systems, etc.—through security and onto the planes.

Gaming’s relationship to the airport extends beyond mere representation. Games participate in airport culture at the same time that the culture of air travel participates in videogaming. Self check-in kiosks and security checkpoint labyrinths demand to be navigated in real life, just as the airport level asks to be explored in the videogame. In either context, it seems one is always playing through the terminal.

At first blush, the relationship between airports and airport-game-levels would seem to be one of mere representation or simulation. Their shared stake in the development of digital communications technologies, however, leads to integral if sometimes unexpected intersections between both discrete contexts. We read these occasions from the theoretical perspective of mixed realism, which is a way of understanding the interweavings of the virtual, the material, and the social that define the contemporary moment.2

The term mixed realism describes an orientation toward the increasingly omnipresent media-generated virtualities in everyday social life. Where these virtualities have come to be understood as “false, illusory, or imaginary,” their impact on contemporary wired culture is anything but.3 While it may be more or less obvious how the virtual spaces of Facebook or an online banking website participate in the flows of social or financial capital, it can be much less clear how the abundance of fictional spaces—such as that of videogames—stage exchanges between online and offline contexts. The concept of mixed realism offers a methodology for tracing the ways our engagements with these fictional environments constitute participation in real social life away from the screen.

This essay presents a series of vignettes springing from two primary points of analysis: the LAX shooting of November 2013, and the Modern Warfare 2 level “No Russian.” Our goal is to suggest that these two seemingly unrelated events (or call them ‘texts’) exemplify the sort of strange medial exchanges and overlaps arising in contemporary wired culture. The concept of mixed realism helps us to recognize and describe the intersections of air travel and videogaming occurring on scales both tragic and mundane, entertaining and horrific. Understanding how lived social spaces such as the airport are both infused with and extended by media-dependent virtualities will continue to be extremely important as digital technologies proliferate.

Airport Shootings

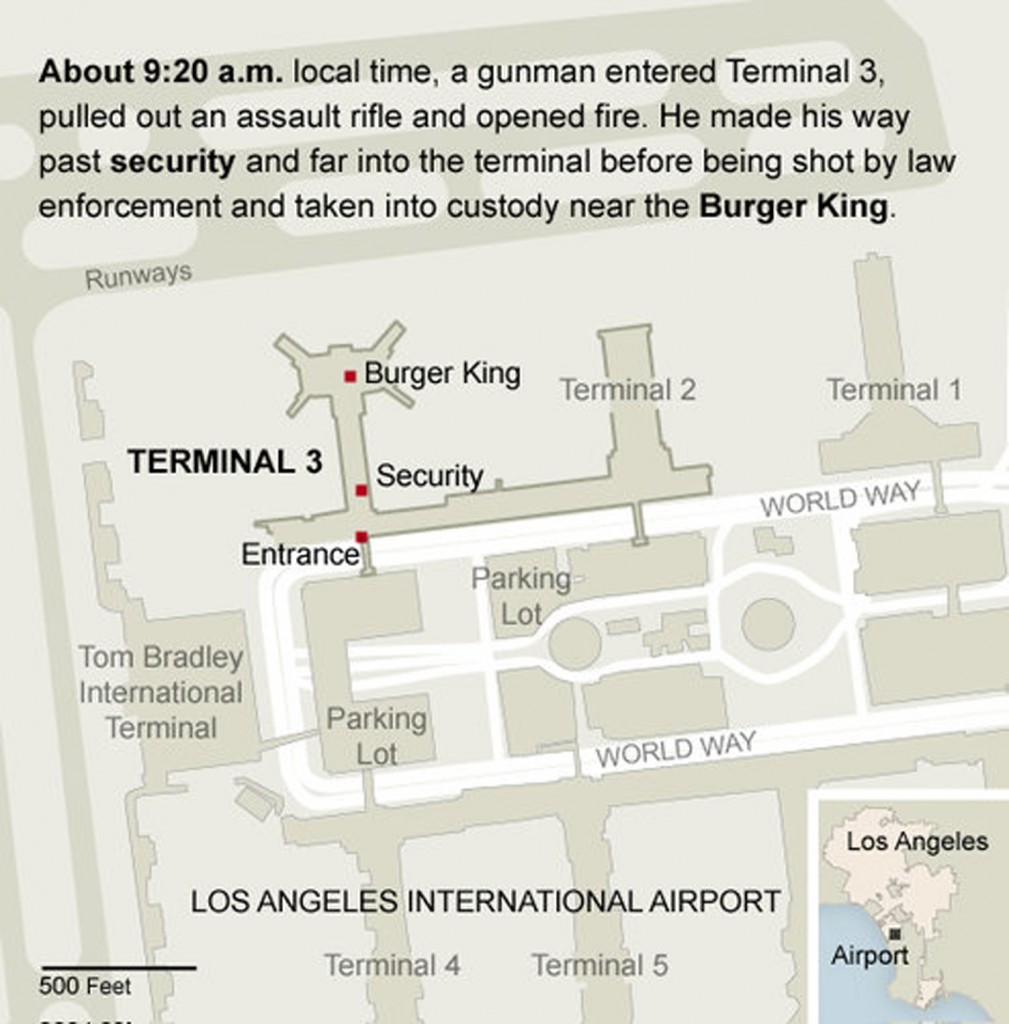

On the morning of Friday, November 1, 2013, a man carrying an assault rifle and over 100 rounds of ammunition broke through the Los Angeles International Airport security checkpoint, shooting multiple Transportation Security Administration officers and “sending travelers fleeing in panic” [Fig. 1].4

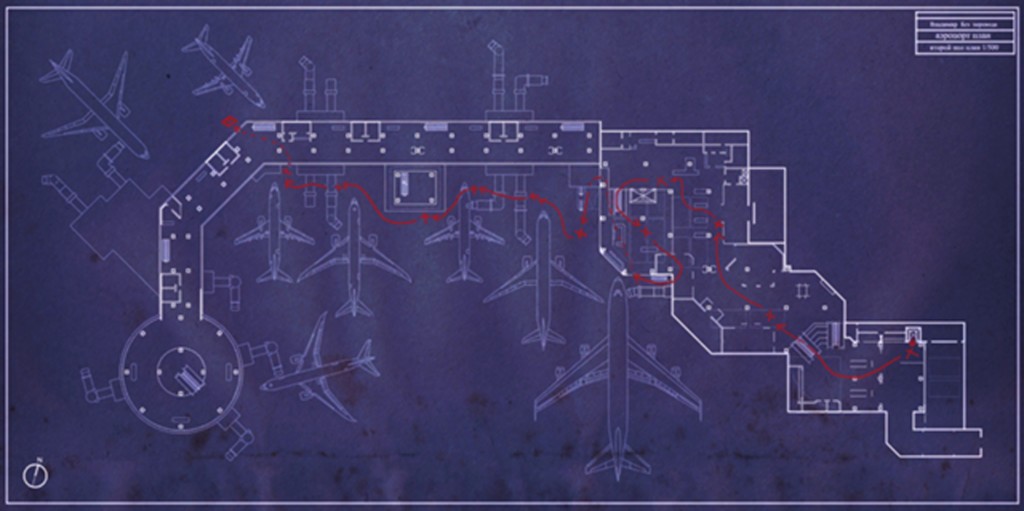

The gunman was eventually shot and detained, leaving a scene eerily resembling the play-space in Infinity Ward’s Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2 [Fig. 2].5

The game’s most infamous sequence, a level called “No Russian,” casts the player as one of four gunmen who slowly make their way through Moscow Airport killing anything that moves [Fig. 3]. Controversy has attended the level since before it was released publicly. It has even been referenced in a terrorist attack on the actual Moscow Airport in January 2011, though that incident bore little resemblance to the in-game action.6

Figure 3. “No Russian” level, Infinity Ward, Modern Warfare 2, 2009, PC, Xbox360, Playstation3, OSX.

Videogames almost inevitably appear in the public discourse in the fallout of high-profile mass shootings; in the case of LAX, however, games did not enter the media’s discussion of the events. When one considers the lengths to which Modern Warfare 2 goes to realistically represent the first-person experience of assaulting an airport, it seems hard to believe it wasn’t a part of the storyline in the aftermath of the LAX shooting.

When games come up in mass media contexts, discussion tends to revolve around questions of realism. As Ian Bogost notes, “[…] moral outrage over videogames’ violence was possible only once they could make reasonable claims to realism.”7 Alexander Galloway identifies two dominant conversations in the media–as well as in some academic disciplines–about realism in videogames: the tendency toward highly detailed verisimilitude and the “Columbine Theory,” or the notion that videogames instigate violence.8 The Modern Warfare games exemplify both. For instance, “No Russian” deploys an intense blend of airport minutiae and recognizably vivid, first-person shooter virtual violence. Metal detectors, fluorescent lights, directional signage, LED displays, simple square tile flooring (you can almost feel your shoeless feet on it as you queue for the metal detector), the modular interior geometry—all of these details point to the architecture of the everyday airport security checkpoint, a point charged with tension but also infused with banality.

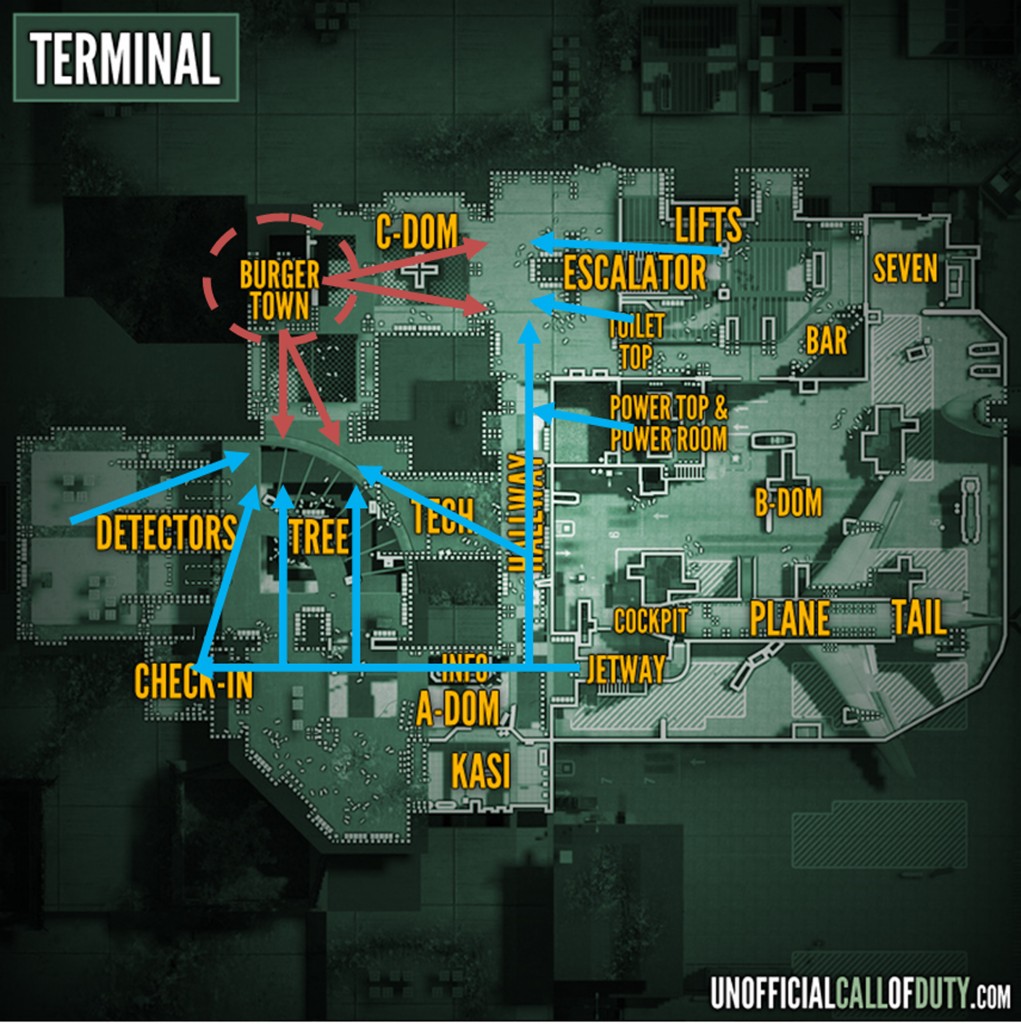

There are, actually, two discrete airport layouts in Modern Warfare 2. The “No Russian” level gets rearranged and repurposed for the multi-player map “Terminal,” with lines of sight opened up and the airport minutiae readymade for strategic play.9 Here the havoc of “No Russian” seems to have already occurred, and the players inhabit a wrecked, post-shooting airport terminal, with luggage scattered about and blood on the floor. The realism of this scene arguably becomes even more immersive and alluring as one is invited (if eccentrically, via gun induced violence) into the nooks and crannies of an everyday airport [Fig. 4]. Even the guns are hyper-realistic, with unique serial numbers clearly printed on each weapon. As the Columbine Theory goes, realism immerses the player qua shooter in a virtual environment free of consequences, which therefore has the potential to numb them to the horrors of the actual violence they rehearse in virtual pantomime on screen.10 And, yet, the most unrealistic thing happening in these games is the violence.

But the relationship such a scene of interactive virtual violence bears to the reality it invokes is much weirder than mere mimesis or mimicry. Games not only reflect the real world—they enact it, and interact with it. Because videogames supplement their depictions with what Alexander Galloway calls “the phenomenon of action,” representational models are always inadequate to capture the ways digital virtualities relate to contemporary social realities.11 The virtual realities appearing on-screen in games such as Modern Warfare 2 participate in a global wired culture, in which significant interactions in digitally generated environments are an ordinary occurrence. For instance, the Modern Warfare 2 player can activate a drone strike from a laptop—blurring a routine desk job, a deadly weapon of pursuit, and en-couched gameplay. In this sense videogames tend to offer fairly pure expression of what we might call mixed realism: their fictional worlds stage and re-contextualize exchanges with digital technologies that have real world presence and significance.

While the airport is rendered in pictorially stunning detail, what happens in the “No Russian” sequence—or Modern Warfare 2 in general for that matter—is hardly ‘realistic’. Its narrative backdrop is downright ludicrous: the “No Russian” incident is blamed on an undercover CIA agent as part of a shared plot by an Ultranationalist Russian terrorist and a US Colonel to ignite a multi-theatre war between the US and Russia. What this level does is effectively mix with and mix up different social spheres, allowing for new configurations within wired culture.12

In light of the recent LAX shooting, the Moscow Airport of “No Russian” serves as an occasion to ponder further the concept of mixed realism, specifically where digital environments and air travel overlap. In this essay we work through several instances that reveal the overlapping of virtual environments and actual airports. The perspective of mixed realism illuminates how airports as places of video game pursuit depend on the everyday pursuits of commercial air travel, which, in turn, are increasingly interpenetrated with playful virtual spaces.

Beignets & Burgers

At our home airport, Louis Armstrong International, a small café in the main terminal sells beignets—the locally acclaimed fritters doused liberally with powdered sugar. This treat is more commonly associated with the French Quarter, and specifically the tourist destination Café Du Monde. Nevertheless, the beignets in our airport serve to authenticate the space, to stamp it as New Orleans. Airline crews and travelers passing through can get a vicarious taste of the city in the airport, regardless of whether they actually “go there” to participate in local activities and gustatory rituals.

Arriving at Louis Armstrong, as you leave your arrival gate—in the A, B, C, or D concourse—you end up in the main terminal, closer to your destination, close enough to purchase and consume beignets [Fig. 5]. Alternatively, it could be the last thing you devour before passing through security checkpoint, on your way out of New Orleans.

The presence of beignets at our own airport is a naturalizing part of air travel: the deep fried pouches of dough remind us that, even at the airport, we are somewhere real, in a place accentuated by the signs and textures of an authentic region. (That our own airport in New Orleans lacks a Starbucks in its terminals may at this point feel like a violation of the natural order; but let us hold that matter in abeyance for now.) Airport foodstuffs serves to some degree to transport us somewhere else—outside the end-to-end flow of a plane trip—to ground us in a place we have traveled through or to. Even at its most generic, travelers can expect that at almost any airport they can sit down at a TGIFriday’s or a Fox Sports Zone during a standard hour-long layover and enjoy a beer, some form of chicken wrap with ranch dressing, and fries—and thereby feel something like an evening at the local sports bar or mall food court. Even when such franchises are in actuality sports bars, their presence at airports is strictly simulacral: the point is to ground passengers in an imitation of something (itself generic) that exists primarily beyond the distortions and distensions of airport space-time.

Likewise, the beignets at the New Orleans airport entice passengers with a taste of the city without ever having to head to the French Quarter—or more likely, for those who are nursing a hangover on their way back home. The beignets, even though they are not ‘real’ (i.e., not from Café Du Monde), nevertheless confirm a sense of stable location, conferring on the airport a sense of place far from the airport gates and boarding announcements: they go beyond real, they are hyper-real, endowing the “non-place” with as-if real spatial qualities.13

And in a perverse turn, like Disneyland for Jean Baudrillard, the beignets—precisely by being obviously simulacral souvenirs—turn out to prop up all the normal, drab operations of everyday air travel. The beignets confer authenticity through hyper-real imitation. The costumes of pilots and flight attendants, the security checkpoint rituals, the lines of shuffling passengers—all these procedural theatrics pass under the radar of the unquestionably real, while the indelibly edible and heavily signifying beignets bubble and spurt in their fry oil baths. The theory of mixed realism focalizes all these layers of realism and hyper-realism, place and non-place, to see how they coexist and cohere. We don’t flinch at the beignets. We consume them and move along.

Surprisingly similar is the function of a small Burger Town franchise in the virtual Moscow Airport of Modern Warfare 2. Players might notice the thinly veiled approximation of Burger King nestled obliquely in the corner of the second floor of the “No Russian” level [Fig. 6]. Passing slowly through the carnage of bodies and abandoned luggage, the fast food restaurant offers little more than a bland backdrop, a generic signifier of the airport food court. With time to linger, however, players will find that the stall is open, and marginally interactive. You can duck in behind the counter and shoot up the rows of pre-packed burgers warming under heat lamps, awaiting customers who will never arrive. These exploding burgers contribute something to the realism of the scene—weirdly, to a scene already infused with the overtly simulacral. The virtual burgers, like our ‘real’ beignets, insist on the reality of a place through their packaged, reproduced, artificial aura.

This function is all the more clear by the inclusion of the Burger Town in the popular multi-player level “Terminal” [Fig. 7 and 8]. “Terminal” is set in the same airport, but the layout has been significantly reorganized. The rearranged space is more squared, with two somewhat open areas connected by corridors joining the tarmac to the interior. Burger Town occupies a much more prominent position at the intersection of two major throughways. As such, hiding behind the counter between the replica condiments can offer a player protection and easy lines of sight to snipe opponents as they get off the escalator, emerge from that bookstore that’s now an electronics depot, or sprint from security toward the departure gate.14 Here, the Burger Town kiosk cedes its realistic function as an airport eatery and gets repurposed for battle alongside downed soda machines and piles of luggage.

Figure 7. Plan schematics for “No Russian” assault, Infinity Ward, Modern Warfare 2, 2009, PC, Xbox360, Playstation3, OSX.

Figure 8. Unofficial Admin, “Map Callouts — Terminal,” 2012, UnofficialCallofDuty.com. Marked by the authors with arrows demonstrating lines of attack and defense from Burgertown.

In fact, the whole airport level has been transitioned to playground, and its representational reference to air travel and even to a scene of terror recedes behind kill/death ratios,15 clear shot lines, and defendable objectives. And still, the burgers explode when players shoot them. As the new layout accommodates multi-player shootouts, it undermines the realistic representation of a functioning airport and quotidian air travel. At the same time, it retains certain markers of realism. To be precise: the forever-warming burgers have no gamic value. Rather, they proffer a sense that this is a real place, the airport, where we know to expect—and even how to interact with—hyper-real objects.

Boneyards

Rockstar’s recently released Grand Theft Auto V features the most operable planes and most robust flying mechanics in the series to date. That isn’t actually saying much, as none of the planes could be flown in the previous title. In Grand Theft Auto IV (2008), the series’ console returns to Liberty City, its facsimile of New York, under the long shadow of 9/11.16 Rockstar in fact introduced the first flyable plane to the series a little over a month after the towers fell; however, Grand Theft Auto III’s Dodo, a badly damaged Cessna 152 named after a flightless bird, had its wings literally clipped and was programmed to be nearly impossible to fly [Fig. 9].17 Though piloting the Dodo is not a part of any mission, players can successfully get it off the ground, making it the last and only user-flown airplane to appear in Liberty City.

After GTAIII, the series left New York and started to offer planes intended to be flown. The subsequent game in the series, Grand Theft Auto: Vice City (2002), took place in Miami and included flyable floatplanes. The series then moved to the west coast with Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas (2004)—and returned there for GTAV—where it offered eleven fixed-wing aircraft, three functional airports, and Verdant Meadows, an airplane boneyard [Fig. 10].18

Boneyards in real life are where airplanes go to die—or at least to hibernate. They are repositories for old machines and scrap parts, usually located in deserts to minimize the adverse corrosive effects of humidity on aircraft aluminum. They are real places, even romantic in a way—see for instance their Ozymandian appearance alongside Patrick Dempsey in the 1987 Hollywood production Can’t Buy Me Love [Fig. 11].

But boneyards are also creepy and vast, even though they are designed only for pragmatic purposes. From Google Satellite View you can see these spaces in sprawling form lying just outside Tucson, Arizona: chilling reminders of a century of exorbitant airborne firepower, surveillance, and governmentality [Fig. 12].

By and large, the Grand Theft Auto series is about acquisition, the main character’s motivations typically tied to amassing credit of one sort or another. Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas is no different. The game tracks the playable character CJ Johnson’s efforts to make a better life for himself, his friends, and his family. After his release from prison in Liberty City, CJ and his Grove Street Gang reestablish themselves by claiming territory throughout the city from rival gangs. After CJ is expelled from the city and his best friend is arrested by a crooked cop, the rest of the game revolves around CJ gaining enough capital and resources to exact revenge and retake the streets. If a player follows the narrative to the end, CJ amasses plenty of money and street cred as well as a modest gas station and garage, a part-owner stake in a casino, a managing contract with a successful rapper, and any number of safe house properties across three cites, not to mention the abandoned airfield.

What is so strange about including an airplane boneyard in this game is that these are spaces of retirement, archaeological holding bays for excesses of the past. Even in San Andreas, the boneyard initiates a mission to obtain an experimental jetpack, which immediately obsolesces the stunt planes the player has just learned to fly. Planes are old school. There is little that is lively or even tangibly valuable in boneyards. Unless, that is, you are involved in the speculative finance operation of buying and leasing used aircraft (or parts), a profitable if risky business—but hardly a romantic enterprise. It’s basically office work and mundane logistics.

Perhaps this is precisely why Grand Theft Auto deploys the boneyard: it is a crystalized symbol of symbolization, a space for the figuring of abstract value in a reified form. These are not really planes, they are parts of planes. They are not valuable as such, unless hitched to sweeping systems of value, exchange, and power—systems that do in fact exist.

When you start looking for airplane boneyards on the Internet, like most things, you find images and stories of them everywhere [Fig. 13]. With some of the images, it’s hard to tell if they are real or fabricated. Indeed, these places seem to exist exactly in the strange realm that mixed realism exposes: the boneyards both stand for something real outside and depend on a becoming-real of new media spectation and consumption, framed by our small screens while representing and perpetuating junk space and big money.

Figure 13. Tech. Sgt. Bennie J. Davis III, Boneyard002, 2012, digital photograph, Airman Magazine (Flickr).

There is a YouTube video that went viral a couple years ago that begins by panning across a troop of 20-somethings hanging out in a boneyard; suddenly they break into a breathtaking, highly choreographed sequence of parkour and free-run moves that take them over, under, and through the dormant airplanes: rebounding off fuselages, balancing on and bouncing off wings, climbing out of overhead luggage bins, and diving out doorways [Fig. 14].19 “The Takeover,” as it is called, is a thrilling few minutes of online adventure, and it reflects perfectly how the boneyard exists in a matrix visible through the concept of mixed realism. The boneyard appears as a stage and as a real place: it is exploited as a spontaneous and unusual space for play and pursuit, and yet gains purchase as a recognizable, able-to-go-viral set piece for digital video production and consumption. The video exposes all its staged artifice as nothing less than the materiality of super-modern life: retired commercial airplanes are rather easily reconceived as a playground, streamed through the video sharing service of YouTube, network of distraction par excellence. You could watch it on your cell phone the next time you are stuck at the airport, waiting for a flight. In fact it is precisely at this possible juncture, waiting in an airport watching “The Takeover,” that the theory of mixed realism again becomes useful: it helps to explain how the everydayness of the airport merges with the pursuit of fun in a re-mediated video on demand, a context that folds the present space of air travel into a vibrant flashing fiction. The lines between fiction and reality blur, mediated by handheld devices and little personal screens.

Figure 14. tempestfreerunning, “Airplane Graveyard Vs ProFreerunners: THE TAKEOVER,” 2013, YouTube.com.

Cell Phones

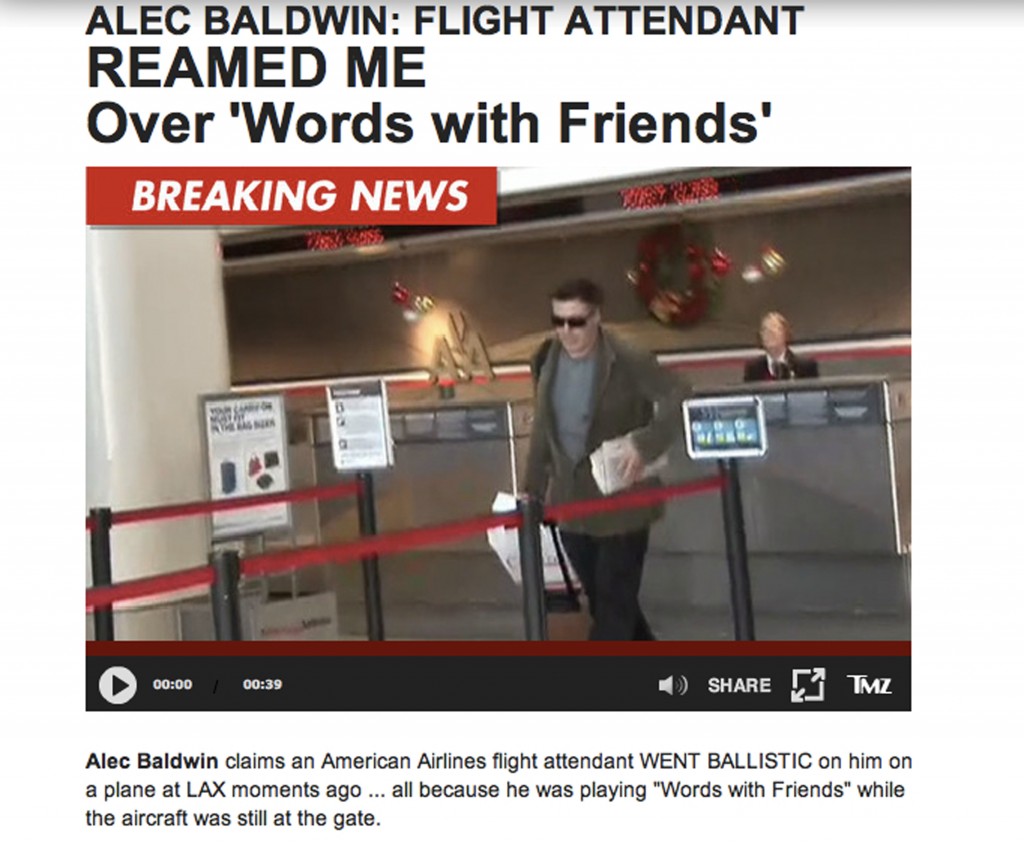

In late 2011 at LAX, Alec Baldwin was kicked off an American Airlines flight for refusing to turn off his phone after the aircraft door was closed.20 He was playing the game Words with Friends, and when the flight attendant demanded he shut down his personal device, allegedly he got up in a huff and stormed to the lavatory, slamming the door so hard that the captain of the flight became alarmed and called the crew to see what the disturbance was [Fig. 15].21

In the brouhaha that ensued, Baldwin was captured by paparazzi coming off the plane and being rebooked, appearing slightly disheveled and publicly shamed [Fig. 16]. This event was quickly composted into fecund material for a Saturday Night Live skit, in which Baldwin himself played the American Airlines captain apologizing to Alec Baldwin for the airline’s blunder [Fig. 17].22 The incident whipped up afresh the debate about whether we really need to turn off our cell phones in flight—a topic that now is old news, as the FAA has officially lifted some restrictions on electronic devices on planes under 10,000 feet.23

Along these same lines, in April 2013 an article made its way around the Internet with the sensational title “How a Single Android Phone Can Hack an Entire Plane.”24 Less interesting than the truth-value of this article was the provocation it presented: that commercial air travel might be increasingly, dangerously unmanned. Aircraft have always depended on a litany of complex, networked, redundant technologies to give passengers more or less smooth, reliable flight. Yet the perceived threat posed by an ordinary phone revealed latent anxieties about the place of the virtual in this heavily real space [Fig. 18].

Virtuality mediates all manner of ordinary activity. It seems odd to think human air travel might be considered especially susceptible to digital interaction, as if it exists in a realm where boundaries of virtual and real must be vigorously policed. Whether we are dealing with airports in video games, or the gamic possibilities of actual air travel, ubiquitous technologies permeate these sites and the virtual/real dichotomy falls short.

That air travel might be something we interact with, that we play—this is the gamut of mixed realism, a theory for how we live in a world that constantly disturbs neat categories of on screen and off. Flight attendants may no longer ask passengers to put cell phones and electronic devices in their “off positions”—but the matter of being in “airplane mode” is no less murky than it has been for some time.

Coda

To return to where we began: following Paul Anthony Ciancia’s assault on LAX, the airport was delayed for hours. The New York Times slideshow (it became another online spectacle, after all) shows the scene of the crime, police officers swarming the terminal—and passengers milling about after the shooting, checking their phones, and waiting, waiting, waiting [Fig. 19].

Some of the photographs taken around this event make it look like barely an emergency at all. It almost appears as though passengers and workers are more annoyed that their day has been interrupted—another damn delay at the airport. And at least one of the images should look strangely familiar: the aerial view of one tarmac scene suggests a vantage point, a tactical summary of the landscape. Indeed, this image was no doubt captured by a helicopter hovering above the airport, targeting the site for the sake of newsworthy reconnaissance.

Although Ciancia was only 23 at the time of the shooting. And yet—perhaps because it did not take place at a high school or on a college campus—the question of video games in the shooter’s past was never raised. And unlike the game level “No Russian,” this was not a mass shooting incident: the killer was targeting TSA agents specifically. (Apparently Ciancia was carrying a “note” with “antigovernment and anti-T.S.A. ramblings.”25 ) It would seem that this rupture in the fabric of everyday airport life had nothing to do with its first-person shooter digital counterpart.

And yet, in the aftermath one passenger was quoted as saying, “If he would have come up the ramp, he would have had a field day with all the people lying on the ground, like me.”26 It is the ordinary passenger who recognized the airport as a game space, replete with strategic possibilities for interactive pursuit.

Consider the info-graphic that accompanied the New York Times coverage of the event. It is here, innocuously online, that we find ourselves to be not too far from the multi-player “Terminal” map of Modern Warfare 2. What we find in this semiotic matrix is a swarm of overlapping, collaborating registers involving fun, fiction, seriousness, and stark reality. It is difficult to get oriented in this airport playground, this ambiguous zone of pragmatics and pursuit. The New York Times info-graphic makes this disorientation plain with its bold heading, as if to ensure we know that even here, both tactically and mundanely, there’s a Burger King in play [Fig. 20].

- The phrase “ordinary affects” is the anthropologist Kathleen Stewart’s, and stands for the amalgam of spontaneous and scripted everyday scenarios, gestures, and technologies that shape and frame contemporary American life. See Kathleen Stewart, Ordinary Affects (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007). ↩

- Timothy Welsh develops his concept of mixed realism in Mixed Realism: A Theory of Fiction for Wired Culture (University of Minnesota Press, forthcoming). ↩

- Pierre Lévy, Becoming Virtual (New York: Plenum Trade), 16. ↩

- Jennifer Medina and Ian Lovett, “Security Agent Is Killed at Los Angeles Airport,” New York Times, November 1, 2013. ↩

- Infinity Ward, Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2, Xbox360, PS3, Windows (Activision, 2009). For those not familiar with the Call of Duty franchise, these games are realistic yet cinematic, military-themed, first-person shooters. The Modern Warfare series began in 2007 with Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare, and marked the first in the franchise set in the contemporary period. The series is extremely popular. Within twenty-four hours of its release in 2009, Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2, doubled the record-breaking weekend box office sales of Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight (2008). Initially revered for its tight controls, realistic graphics, innovative multiplayer, and self-conscious narrative, successive releases failed to develop its game mechanics. More recent editions compensate for repetitiveness with increasingly unbelievable set-pieces and hyperactive game modes and, yet, still enjoy wild commercial success. As a result, the hardcore gamer community tends to revile Modern Warfare as a game for more casual and unsophisticated gamers. ↩

- The “No Russian” mission leaked before Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2 even reached store shelves, triggering controversy about the level. The game was then cited by multiple news outlets–in the US and Russia–in a real life terrorist attack on Moscow Airport in January 2011. That attack, however, was carried out by a suicide bomber, making it quite different from the “commando raid” the game depicts. For example, see Robert Mackey, “Russian Media Points to Moscow Airport Attack in U.S. Video Game,” New York Times, The Lede (blog), January 25, 2011 (9:17 a.m.). ↩

- Ian Bogost, “Rage Against the Machines,” The Baffler 24 (2014). ↩

- Alexander Galloway, Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006), 71. ↩

- Modern Warfare 2 includes three game modes: a single-player narrative campaign, a two-player set of challenges called “Special Ops,” and online multiplayer. The online multiplayer offers a suite of different competitive scenarios placing player versus player or team versus team with varying objectives. By far the simplest and most popular is called “Team Deathmatch” which pits two teams against each other to see which can score the most kills of the opposing team members. Success in this format—and really most of the multiplayer modes—depends on a team’s ability to secure and control strategic areas of the map, particularly high-traffic areas where opposing players will attempt to get from one area of the map to another. ↩

- See, for example, Jerald J. Block, “Lessons from Columbine: Virtual and Real Rage,” The American Journal of Forensic Psychiatry. 28, no. 2 (2007): 5–34. ↩

- Though Galloway observes that games are fundamentally an action-based medium, his attempt to outline a concept of gaming realism based on this fact ends up returning to a representational model. To the dominant conceptions of videogame realism (the ‘Columbine Theory’ and “hyper-representational realism”), Galloway adds a third form, “social realism,” which describes the ‘correspondence’ between what happens in the game and the social lives of the player. Citing as examples Under Ash, a game released Syrian publisher Dar Al-Fakr, and Special Forces, a game made by Hezbollah Central Internet Bureau, Galloway argues that their realism comes from giving voice to the ‘restricted code’ of the Palestinian movement. Compared to America’s Army, the American first person shooter on which these Palestinian titles are based, “the engine is the same, but the narrative is different” (82). In other words, their realism results from their narrative strategies, and is thus based in their representational capacity. Likewise, his concept of ‘allegorithmic’ critique, a methodology for assessing the relationship between videogames and social life, depends on a binary representational structure, specifically the allegory. What we are trying to suggest with the concept of mixed realism is that the relationship between air travel and videogames goes beyond allegory. Rather these two social spheres overlap and intersect, such that to play these games is to participate in the culture of air travel and, at the same time, to board a flight is to participate in gamer culture. ↩

- For an article length treatment of the mixed realism of the Modern Warfare series, see Timothy Welsh, “Face to Face: Humanizing the Digital Display in Call of Duty: Modern Warfare.” Guns, Grenades, and Grunts: First-Person Shooter Games. Ed. Gerald A. Voorhees, Joshua Call, Katie Whitlock (London: Continuum, 2013). ↩

- The anthropologist Marc Augé uses the phrase “non-place” to describe sites like airports and other super-modern zones of pure (if also heavily mediated) transition. See Augé, Non-Places: An Introduction to Supermodernity (New York: Verso, 2009). ↩

- “Terminal” originally appears in Modern Warfare 2. It was rereleased as downloadable content for multiplayer play in Modern Warfare 3 (Infinity Ward and Sledgehammer Games, 2011), with some slight changes. For example, the store that joined the hallway to the open area past the metal detectors was changed from a bookstore to a Traube electronics shop resembling a TechShowcase or InMotion. Coincidentally, this alteration tracks with the general downswing in standalone booksellers (Todd Leopold, “The Death and Life of a Great American Bookstore,” CNN, September 12, 2011) and the upswing of airport electronics retailers (Jane L. Levere, “At Airports, a Bigger Push to Sell Electronics,” New York Times, November 28, 2011). ↩

- A typical measure of aptitude in multiplayer games like Modern Warfare, kill/death ratio tracks the number of times a player kills another versus how many times they are killed themselves. A ratio above one is fairly good. ↩

- After the series left the fictional Liberty City following Grand Theft Auto III (Rockstar, 2001), it did return there for Grand Theft Auto: Liberty City Stories (Rockstar, 2005, 2006), which was released on the PlayStation Portable and was later ported to the PlayStation2. None of the planes are flyable in this title either. ↩

- DMA Design, Grand Theft Auto III (Rockstar Games, 2001). Rockstar has stated that they never intended the Dodo to be flown and considered the broken plane something fun for players to play with. They also explained that this was always the intention and was not altered as a result of September 11th, as they felt the core of the game was driving and shooting. See R* Q, “Grand Theft Auto III: Your Questions Answered – Part Two (9/11, The ‘Ghost Town’, The Dodo and Other Mysteries),” Rockstar Newswire, January 5, 2012. ↩

- Rockstar North, Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas, PlayStation2, Xbox, Windows, OSX (Rockstar Games, 2006). ↩

- tempestfreerunning, “Airplane Graveyard Vs Pro Freerunners: THE TAKEOVER,” March 6, 2013. ↩

- TMZ STAFF, “Alec Baldwin Plane Incident — Flight Attendant REAMED ME Over ‘Words with Friends’,” TMZ.com, December 6, 2011. ↩

- Zynga, Words with Friends, iOS Android Facebook (Zynga, 2009). ↩

- Saturday Night Live, Season 37, Episode 9 (NBC, December 10, 2011). ↩

- Airlines and the FAA are currently working out policies for standardized cell phone usage on airliners; on most flights these days it is something of an elephant in the cabin, as flight attendants try to moderate usage and as passengers attempt to still somewhat slyly push the limits imposed on them. ↩

- Jamie Condliffe, “How a Single Android Phone Can Hack an Entire Plane,” Gizmodo, April 11, 2013. ↩

- “Security Agent Is Killed at Los Angeles Airport,” New York Times. ↩

- Medina and Lovett, “Security Agent Is Killed at Los Angeles Airport.” ↩

![[Figure 1. Screenshot, Embedded slideshow, The New York Times online, 2013]](http://ivc.lib.rochester.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/1-1024x1012.jpg)