In this post, I will sketch the roles of sound reproduction technology within Indonesian cultural history in its process of “becoming” a nation.1 However, this is not an attempt to give all-embracing historical details. It is meant to be a short story of audible Indonesian cultural life. Loudspeakers and microphones are the central figures in this story.

In Western tradition, sound has long been an object of anxiety. In order to envision an ideal state, controlling sounds is probably the main object of Plato’s anxiety.2 In Greek mythology, luring sounds of the sirens, inspiring voices of the muses, and unwanted reflected calls of Echo are the subjects of cultural imagination. In a biblical story, the powerful and earth-wrecking voice of God speaks to Moses. Meanwhile, in Islamic eschatology, the blowing trumpets of the Archangel Israfeel are believed to end the world.

In Indonesian tradition, cursing words coming from a mother’s mouth have some powerful effects on her children. According to an oral legend from Sumatera Island, a boy, named Malin Kundang, turns into a stone after his mother cursed him for being ungrateful and disrespectful to his parents.3 Another oral legend, “The Legend of Sang Kuriang” from West Java, tells a different story of how powerful sound is. According to this legend, sounds coming from rice pounders and roosters are able to wake the sun, destroying a man’s dream to marry his own mother. Sound is also believed to have power over ghosts and spirits. Sounds coming from kentongan, a bamboo or wooden slit drum, have the powerful effect of expelling demons. All these narratives tell the power of sound over life (and death); sound inspires and threatens humanity.

Despite the all-seeing metaphors of modernity, the anxiety to control sound still persists. Nevertheless, the sacred meaning of sound as the property of nature and the supernatural (the Divine/s) has been secularized by modern technology. The sacredness is put down under human control. Once, sound reproduction belonged to the gods, but now it belongs to humanity.4 The 19th century invention of sound reproduction in the forms of the gramophone, wireless telegraph, and telephone had proven that humans had control over sound, and the human voice was immortal. The “aura” of sound was unearthed by its mechanical reproduction.5

One might think that the early “magical” invention of sound reproduction only affected life in the Western world, but Western colonization and imperialism also brought this tantalizing modern invention to the colonies. This applied to the colonial scene of Indonesia. In his analysis of the use of modern technology in 19th to early 20th century Indonesia, Rudolf Mrazek points out that cables and wires—even wireless technology—are metaphors for a spatial connectedness between the Western world (the Netherlands) and its colony (the Netherlands East Indies or Indonesia during the Dutch occupation) through sound.6

During his visit to Batavia at the end of the 19th century, W Basil Worsfold, a British traveller, noticed how this magical invention was commonly used. To his amazement, he said, “the telephone, again, is in constant use both in offices and private houses.”7 A century later, in the 1920’s, the Dutch queen sat in front of a microphone and then spoke wirelessly from Amsterdam to her colonial subjects in the Indies. Her distant disembodied voice coming from speakers of radio receivers was heard in the colony.8 Years before, the condition of being connected to distant disembodied voices had already been imagined by a young Javanese woman, Kartini, who would become an icon for the Indonesian women’s movement.9 These scenes show how the uses of modern technologies had also affected life in the colony.

In the early 20th century, Indonesia experienced “the age in motion” (zaman pergerakan). In his study of modern colonial life in Indonesia, Abidin Kusno analyzes this age as the period when political consciousness and modern consumption were on the rise.10 This age fostered the birth of the new Indies, the new colonial subjects, who were politically active and adherents of modern consumption. Modern technologies became commodities consumed by modern colonial society. As a

result, Batavia (now, Jakarta) and other cities in Java like Bandung, Semarang, and Surabaya were the new urban cities connected through modern consumption to other modern cities in Europe.

During the Japanese occupation of Indonesia, the Japanese military authority exploited the connectedness between the speakers and the listeners mediated by sound reproduction technology. In the time of the Pacific War, to gain sympathy and support from the Indonesian people and republicans, the Japanese used radio to broadcast their propaganda. Speeches using Indonesian language, traditional songs and musical instruments, and propagandist news were broadcast from radio stations reaching Indonesians’ public ears.11

In one of the Japanese public propaganda broadcasts, “loudspeakers were set up in forty public locations in Java’s cities” for the Indonesians who did not have access to radios.12 It was a spectacular moment, a fascinated crowd paid attention to the disembodied voices blasting from loudspeakers (Fig. 1). Public radio broadcasting was also a form of popular entertainment at that moment.

Figure 1. Radio loudspeaker in the street during a Japanese propaganda broadcast. Still from the Japanese propaganda film, Perkenan Kemerdekaan Kepada Indonesia, 1944. Image reproduced from the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision/NIOD.

Meanwhile, across the oceans, in Europe, the same technology was used by Nazis to annihilate different crowds. Sounds and voices blasting from the loudspeakers tortured the Jewish people in concentration camps, and they became the soundtracks for the prosecutors. That was the nightmare of mechanical reproduction years before it was “predicted” by Walter Benjamin: “All efforts to aestheticize politics culminate in one point. That one point is war.”13

Sound reproduction technology was indeed introduced by the Dutch into Indonesian cultural life. It brought distant sounds and voices into private houses, blasting through radio receivers and telephones. However, it was the Japanese who brought these sounds and voices outside the private space by mounting loudspeakers in public places to reach wider public audiences.14

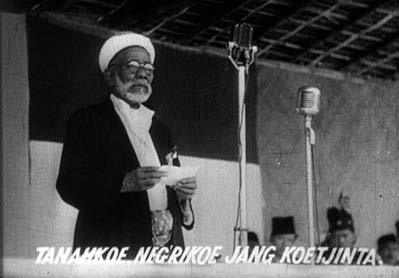

The aural power of modern sound technology was then reused by the Indonesian republican leaders to address their nationalist political views (Fig. 2). It reached the Indonesian public’s ears, and then “sonically” amplified the imagination of the archipelago as one nation; one amplified nation. Benedict Anderson is right when he argues that writing and print culture fosters nationalism.15 However, that culture only fosters the birth of the Indonesian intellectuals. I believe, in the context of the birth of Indonesia as a modern independent nation, loudspeakers and microphones are the products of technology that foster the birth of the nation: binding and amplifying the nation, uniting both the intellectuals and the masses. This sonic attachment is related to auditory culture prevailing at that time. Comparatively, the aura of sound also influences this attachment. The aura binds the speakers and the audiences emotionally. One could argue that aurality nurtures passivity, but in this scene, it had nurtured active participation.

Surkati expresses his gratitude for the Koiso Declaration, which promised independence in the future, September 1944. Image reproduced from the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision/NIOD.

Endang Suryana Priyatna

Lecturer, Universitas Islam “45” English Department

- A longer version of this blog post appears as a chapter in my MA thesis entitled A Story of the Amplified Nation: Sounds and Voices of the Divine, the Body, and the Machine. ↩

- Eric A Havelock, Preface to Plato, (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1963). ↩

- The legend is told as “The Legend of Malin Kundang.” ↩

- Jacques Attali, Noise: The Political Economy of Music, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1985), 87. ↩

- Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility: Second Version,” in The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility, and Other Writings on Media, ed. by Michael W Jennings, Brigid Doherty, and Thomas Y Levin (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2008), 19-55. ↩

- Rudolf Mrazek, “Let Us Become Radio Mechanics,” in Engineers of Happy Land: Technology and Nationalism in a Colony, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002), 161-91. ↩

- W. Basil Worsfold, A Visit to Java with an Account of the Founding of Singapore, (London: Richard Bentley and Son, 1893), 73. ↩

- Mrazek, 165. ↩

- Mrazek, 161. ↩

- Abidin Kusno, “Colonial Cities in Motion,” in The Appearances of Memory: Mnemonic Practices of Architectures and Urban Form in Indonesia (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), 155-81. ↩

- Ethan Mark, “Intellectual Life and the Media,” in The Encyclopedia of Indonesia in the Pacific War, ed. by Peter Post, et al. (Leiden: Brill, 2010), 348-62. ↩

- Mark, 357. ↩

- Benjamin, 41. ↩

- I am not certain whether there is a connection with this, but the most popular loudspeakers in Indonesia are made in Japan. In general and everyday use, most Indonesians usually name loudspeakers in the mosques as Speker TOA (TOA Speaker). TOA is a Japanese electronic consumer company, producing various types of loudspeakers and public announcers. ↩

- Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (New Edition) (Verso, 2006). ↩