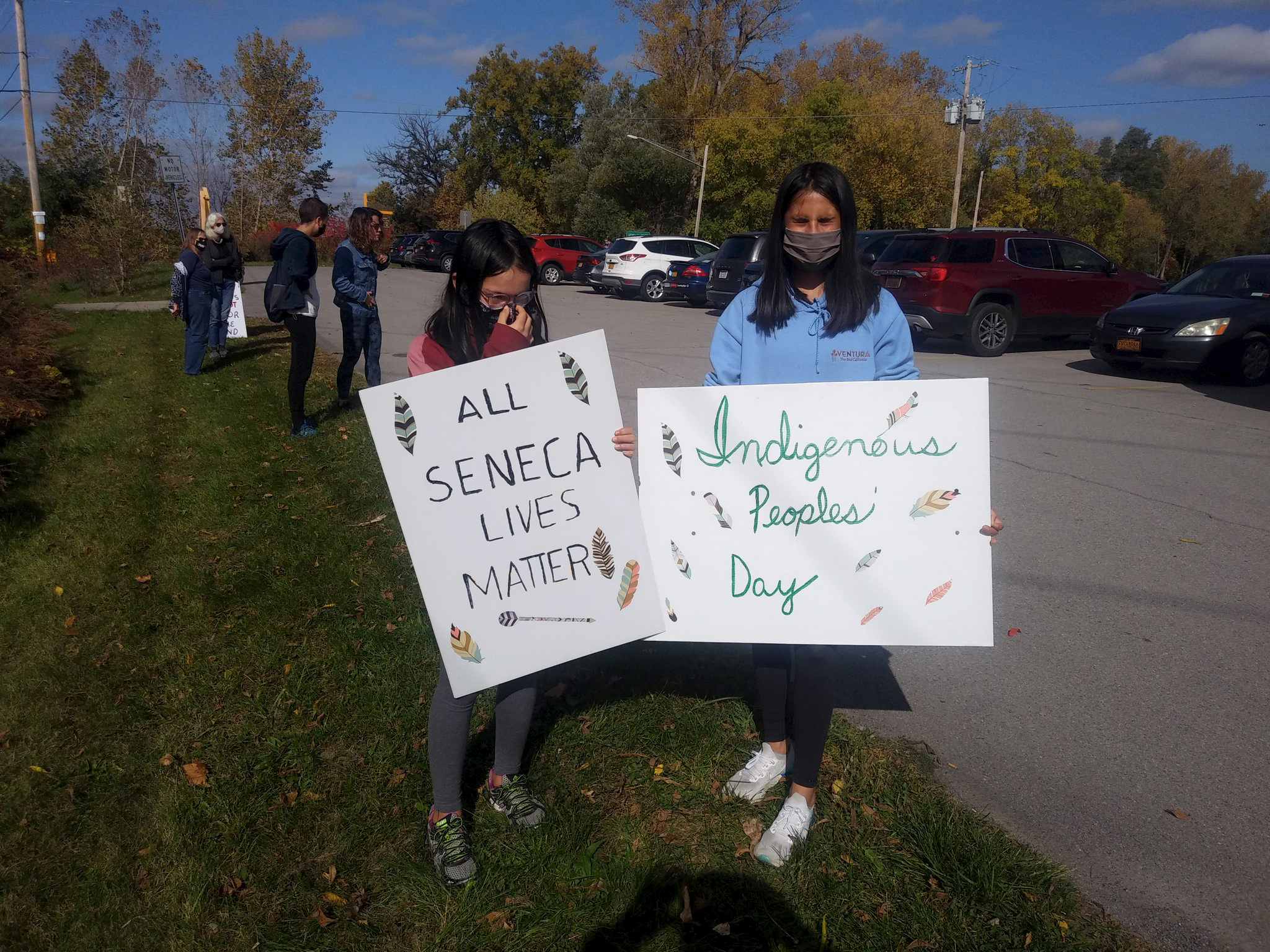

Featured Image: Two young Mexican-American protesters at the 2020 Indigenous People’s Day rally at the Seneca town of Canawaugus. Photograph courtesy of Michael Leroy Oberg.

In January 2019, the University of Rochester hosted a “Black Studies Now” roundtable, in which faculty members, joined by the distinguished feminist scholar Hazel Carby, assessed the current state of Black Studies at UR and imagined its future. The University of Rochester is located on the ancestral homelands of the Seneca nation of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy; today, the university sits within a few hours of multiple Indian reservations. Carby alluded to this geography—and the exigencies of place—when she emphasized the importance of thinking through issues around indigeneity as we chart the future of Black Studies. What does it mean to think through issues of indigeneity? What does the concept of indigeneity offer Black Studies?

We might begin with a definition. In colloquial terms, indigeneity generally refers to the status of being original—or native—to a particular place. International organizations have added greater specificity, even as they typically avoid rigid definitions that could undermine a people’s self-identification and self-determination. In the 1980s, the International Labour Organization’s (ILO) Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention defined Indigenous peoples as descendants of populations “which inhabited a country or geographical region during its conquest or colonization or the establishment of present state boundaries” and “retain some or all of their own social, economic, cultural and political institutions.”1 While imperfect and not without controversy, the ILO’s two-part definition provides us with a foundation from which to think about indigeneity. Indigeneity raises questions of sovereignty, nationhood, and land, as well as different ways of thinking about citizenship and belonging.

Above all, indigeneity should direct our attention to the Native peoples on whose homelands we sit. The United States currently recognizes more than 570 Native nations; others are recognized only at the state level, while still more remain without formal recognition. What does it mean to think about Black Studies in a region surrounded by Seneca historical sites and vibrant Seneca communities; in a state that finally emancipated enslaved men and women just as state and private interests engineered the appropriation of Haudenosaunee land; in a country in which Native dispossession and Black chattel slavery, forced assimilation and Jim Crow, coincided and in many ways reinforced one another? Given my own perspective as a historian of Native America, Hazel Carby’s comments led me to consider what can be gained from critical explorations of the intersections of Black and Native histories and experiences within the boundaries of what is currently the United States—to consider, moreover, what Black Studies can gain from Native Studies and vice versa.2

The questions I am asking and the topics I am exploring are not new. Carter G. Woodson, a founding member of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, published “The Relations of Negroes and Indians in Massachusetts” in the Journal of Negro History in 1920, and comparable studies followed.3 Such inquiries proceeded unevenly throughout the century, spurred by the roughly contemporaneous establishment of academic Black Studies and Native Studies programs in the 1960s and 1970s.4 The last two decades have proven particularly fruitful. In 2000, historians Tiya Miles and Celia Naylor and community organizer Stephanie Morgan co-organized a national conference entitled “‘Eating Out of the Same Pot’: Relating Black and Native (Hi)stories.” The gathering revealed a collective hunger for public discussion of these shared stories; attendees included “scholars, artists, activists, [and] community members,” who identified as Native, Black, Black Indian, and white.5 “Eating Out of the Same Pot” resulted in an interdisciplinary anthology published six years later entitled Crossing Waters, Crossing Worlds: The African Diaspora in Indian Country.6 The primarily African Americanist contributors to the volume contend that Native America has been “a critical site in the histories and lives of dispersed African peoples.”7

Scholarship on the intersection of blackness and indigeneity, of Black and Indigenous peoples, continues to cross disciplinary boundaries. Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies scholar Tiffany Lethabo King’s The Black Shoals: Offshore Formations of Black and Native Studies was published in August 2019.8 Chad Infante, who recently joined the English Department at the University of Maryland, is working on a manuscript that uses feminist and queer theory to compare the oft-cited works of Black and Native authors such as Audre Lorde and Leslie Marmon Silko. Kyle Mays, a Black and Saginaw Anishinaabe scholar, has previously written about indigeneity in Detroit, a city often depicted exclusively within a Black-white paradigm, as well as about the linkages between US blackness and indigeneity in Indigenous hip hop.9 He is currently writing a book tentatively titled Black Belonging, Indigenous Sovereignty: Black American and Indigenous Histories in Unexpected Places. Mays, who has a dual appointment in UCLA’s Departments of African American Studies and American Indian Studies, was trained as a historian, and his new book project traces Black and Native histories “from the foundations of the United States until the present.”10

As a U.S. historian myself, I am enthusiastic about Mays’s project because of the scope of historical intersections and exchanges that to date have been unevenly explored. For generations following European settlement, encounters between African and African-descended peoples and Native Americans were characterized at least in part by interdependence and shared experience in free and unfree labor. Intermarriage resulted in kinship ties, and this was especially true when the wife/mother was a Native woman from a matrilineal society. Intermarriage also resulted in cultural fusion and multilayered identity formations.11 Over time, Euro-American observers, intent on making nonwhite populations legible, recorded Native individuals (with or without African descent) as “negro,” “mulatto,” “colored,” “African,” or “Black.” This documentary record served as an instrument of Indigenous erasure. After all, it was Indigenous—not African-descended—peoples who had prior claims to land in the Americas, claims that could at least theoretically be evaded with the stroke of a pen. The record also denies the possibility that one could be both Black and Indigenous, although European-produced documents did not always align with how individuals saw themselves or how their families and communities viewed them.

An entire subfield of Black Indian Studies has emerged in recent decades to explore the historical and contemporary experience of being Black and Indigenous. Black Indians challenge reductive, binary-dependent ideas about race, but for many this identity became fraught with the hardening of racial categories within as well as outside Native nations in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Scholars have dedicated particular attention to the African-descended peoples who lived among Native nations in the southeast. In the first decades of the nineteenth century, many Cherokees, Creeks, Chickasaws, Choctaws, and Seminoles—the so-called Five Civilized Tribes—endured forced relocation from their homelands. By this time, some of the men and women who traveled trails of tears to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) had become slaveholders, and their slaves, as well as some free Blacks, accompanied them on the journey. The experience of enslaved Blacks in Native America shared much with enslaved individuals throughout the South, but the historian and Africana Studies scholar Celia Naylor argues that “the stories of enslaved Africans in Indian Territory challenge . . . a monolithic African American cultural identity in the United States, whether in the nineteenth century or in the present day.”12

Blackness carried layered meanings in Indian Country that disrupt the Black-white binary that prevailed in much of nineteenth-century U.S. society. During the Reconstruction period, for example, the experiences of Black freedpeople, free Blacks of Native descent, and African Americans who migrated to Indian Territory in search of a refuge from white supremacy differed, sometimes significantly. Nor did these groups necessarily identify with one another in any meaningful way. The historian David Chang’s examination of racial politics within the Creek Nation reveals that Black Creeks—freedpeople as well as Blacks of Creek descent who had never been held in bondage—strongly identified with the Creek Nation while only gradually adopting a broader racial consciousness.13 Chang points to the 1898 founding of the Inter-national Afro-American League as an illuminating example of evolving (but not inevitably competing) loyalties. The men who gathered in the capital of the Seminole Nation likely did not select “Inter-national” in reference to a global Black struggle, as twenty-first-century readers may imagine. Rather, Chang suggests that the term acknowledged the nationhood of Native nations in Indian Territory; the new organization underscored founding members’ position within these nations while recognizing a need for a racially-based organization that transcended these boundaries.14

Freedmen’s path to citizenship was more difficult in other Five Civilized Tribes, and in some cases, such as for Chickasaw freedmen, it proved virtually impossible despite freedpeople’s dogged efforts. Two pieces of late nineteenth-century federal legislation—the Dawes Act and the Curtis Act—further constrained the possibilities of belonging for Indians of African descent. The Dawes Act set the terms for the allotment of tribal land; it authorized the division of tribal lands into plots that were allocated to heads of families and individuals. Native nations in Indian Territory were initially exempt from this legislation, but that changed with the Curtis Act. The federal commission tasked with determining tribal membership for the purposes of allotment adhered to the so-called one-drop rule and recorded all individuals with known African descent on a separate roll than non-Black tribal members, who were recorded by blood quantum. As the historian Alaina Roberts observes, these acts “reshaped the enrollment policies of Indigenous tribes throughout North America, constructing a constituency based on blood quantum rather than on kinship, adoption, or shared history.”15

These histories have spurred difficult questions that continue to be debated within and outside academia. Roberts, for example, is the descendant of Chickasaw freedpeople who were denied citizenship by the Chickasaw Nation. As such, although she is of Chickasaw descent, and although she has ancestors who lived their entire lives among the Chickasaws, Roberts likely will “never have the opportunity to enroll” as a Chickasaw citizen.16 Roberts emphasizes the extent to which the Dawes Commission laid the groundwork for subsequent disenrollments based on the logic of “blood.” In 2018, she published a brief essay in The Western Historical Quarterly calling on historians to speak out against the actions taken by some twenty-first-century tribal nations to disenroll members, an effort that has affected Black Seminoles, Black Cherokees, and many others, including previously-enrolled tribal members with no known African ancestry.17 This issue continues to divide Native communities, but some Native Studies scholars have spoken out in various ways as well. After Cherokee tribal leaders justified the disenfranchisement of Cherokee freedmen in 2007 on the basis of Native sovereignty, Jodi Byrd wrote that the Nation could “resolve the issue through a radical act of sovereignty that restores the Freedmen to full citizenship immediately.”18 Robert Warrior urged the principal chief of the Cherokee Nation to “follo[w] some of the best examples of Cherokee history rather than the morally corrupting and exclusionary ones he and his supporters have chosen thus far.”19

At the 2019 meeting of the Organization of American Historians, Roberts raised another thorny question when she delivered a paper entitled “Can people of African descent be settlers?” Following the African Caribbean poet Kamau Brathwaite, Jodi Byrd has used the term “arrivant” to refer to peoples who arrived in the Americas through violent coercion, but Roberts insists that this vocabulary does not account for the active role freedpeople played in the settler colonial project following Reconstruction.20 Kyle Mays makes a somewhat comparable point with regard to the late twentieth century by citing the work of Black radicals who used the history of Native oppression—with no acknowledgement of continued Native presence and struggles for sovereignty—to advance Black liberation agendas. Mays points, for example, to James Boggs’ and Grace Lee Boggs’ 1970 essay “The City is the Black Man’s Land,” in which the Detroit-based activists argue that Black people must take over city politics. While praising the Boggs as revolutionary thinkers, Mays also worries that from the perspective of Native people living in Detroit and other cities, “The City is the Black Man’s Land” effectively advocated the replacement of one settler power for another.21 The tendency of the city’s Black leaders to refer to themselves as “pioneers” underscores this point.22

These tensions remind us, as Tiya Miles has suggested, that liberation for two oppressed peoples has often been viewed as a “mutually exclusive” enterprise, for reasons that have deep historical roots.23 But we could also, as Miles herself has done at times, foreground those moments, however fleeting, when Black Americans and Native Americans—not mutually exclusive categories—formed alliances and coalitions in defiance of the federal government’s and white settlers’ attempts to divide them. The story of the military alliances between Seminoles and free Blacks and escaped slaves has been frequently told, but more recent alliances are equally instructive. The Society of American Indians (SAI), an Indian-led Indian rights organization founded in 1911, was modeled at least in part on the recently-created National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and W. E. B. DuBois became an associate member. The same year, DuBois and Charles Eastman, a Dakota physician and founding SAI member, traveled to London to participate in the United Races Congress. While certainly not evidence of a close alliance, Kyle Mays persuasively argues that DuBois and Eastman demonstrated “parallel opposition . . . to similar forms of oppression” and shared a “common stance against colonialism.”24

Although in the late 1960s Vine Deloria, Jr., a forefather of Native American Studies, emphasized the historical and contemporary differences between “the red and the black,” the protest movements of this period produced multiracial and, given Native nationhood, transnational coalitions.25 Sometimes, as in Seattle and other urban areas, alliances formed out of shared problems and agendas, while in other cases, individuals, groups, and organizations stood in solidarity with one another, as when the Black Panthers supported Native fishing protests and the American Indian Movement’s occupation of Wounded Knee, South Dakota. More recently, the anti-pipeline protests at Standing Rock and the Black Lives Matter movement have also been sites of Black-Native solidarity, however imperfect.

When I reflect on Hazel Carby’s comments at the “Black Studies Now” roundtable, I return to the need for sustained engagement between Black Studies and Native Studies, engagement of the type advocated by the editors of Crossing Waters, Crossing Worlds. As I hope is clear from the above discussion, Native Studies has at least as much to gain from such intellectual exchanges as does Black Studies. Yet the challenges are many. These are often painful conversations. Robert Warrior, who offered concluding comments at the 2000 conference at Dartmouth, observed that the gathering evoked intense emotions, as well as hostility and at least one occasion of threatened violence.26 Other challenges are more prosaic. Institutionally, Black Studies and Native Studies departments emerged around the same time, and on many campuses, they have struggled for legitimacy and stability ever since, sometimes not as departments but as tracks or centers under the umbrella of Ethnic Studies. In what often appears to be a zero-sum game, the incentives for protecting one’s own turf are real, and the structure of twenty-first-century universities can make it difficult to bridge the siloes.

Here at UR, we have an additional yet related challenge: our institution currently offers little in the way of Native American Studies research or course offerings. I arrived at UR—and in Haudenosaunee Country—in fall 2017. Hired as a U.S. women’s and gender historian, to date my research and much of my teaching center on the history of Native America. Having previously taught at public institutions in the West, I have been struck by the relative absence of Native Studies on this campus, and my presence in this forum speaks to this. I am a white scholar, and I am not a specialist in the topics I have raised. I am, however, personally, intellectually, and pedagogically committed to a robust Black Studies program, and I am currently one of a handful of faculty members to whom people across campus turn when there is a perceived need for attention to Native issues. It seems to me that if we want to answer Carby’s call in a meaningful way, we need more, and we need a broad-based campus commitment to Native Studies. Thus, Carby’s roundtable comments provide our campus community with an opportunity to reflect on the future of Native Studies as well as Black Studies. This reflection is timely, as universities throughout the U.S. and Canada have been and will continue to face pressure to consider their obligations to the Native peoples on whose homelands they are located.

My purpose is not to distract or detract from the spirit of January 2019’s “Black Studies Now” roundtable, which both assessed the state of Black Studies at the University of Rochester and made a case for the moral urgency of the field in this time and place. Rather, my contribution has been to reflect on what can be gained by viewing these projects—Black Studies and Native Studies, and the many intersections that arise through these fields—as co-constitutive. Tiffany Lethabo King begins The Black Shoals by recounting the visceral experience of listening to an Anishinaabe woman’s story of her people’s history. Hearing the story unmoored King: “There was something about the way this Anishinaabe woman spoke of genocide. I knew that it had everything to do with now, with tomorrow, with yesterday. With then. And more so, it had everything to do with slavery.” For King, the Anishinaabe woman’s story proved transformative, leading her to embrace a Black radical politics that is her inheritance, a radical politics that “proceeds and moves toward Black and Indigenous futures.”27

- Office of the United Nations Higher Commission for Human Rights, “The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples: A Manual for National Human Rights Institutions,” 2013, accessed August 27, 2019, https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/IPeoples/UNDRIPManualForNHRIs.pdf. This manual also includes alternative definitions proposed at various times by the United Nations and other entities. ↩

- This is not to suggest that these issues are specific to the United States. Indeed, given the global nature of both Black Studies and Indigenous Studies, scholars are currently exploring the intersection of Black and Indigenous experiences in a variety of contexts. This essay’s confinement to the United States is the result of limitations of space and my own expertise. ↩

- Carter G. Woodson, “The Relations of Negroes and Indians in Massachusetts,” Journal of Negro History 5 (1920): 45-57. Laura Lovett analyzes Woodson’s publications as well as comparable studies published in the same journal in this period in “‘African and Cherokee by Choice’: Race and Resistance under Legalized Segregation,” in Confounding the Color Line: The Indian-Black Experience in North America, ed. James Brooks (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002), 208-09. ↩

- Perhaps the most significant book to emerge out of the intellectual and political movements of the late 1960s and 1970s era did not appear until the 1990s. Jack Forbes, a scholar of Powhatan-Renape and Delaware-Lenape descent, published Africans and Native Americans a year after his retirement. Forbes helped found the Native American Studies department at the University of California-Davis and also published in the field of African American Studies. See Jack Forbes, Africans and Native Americans: The Language of Race and the Evolution of Red-Black Peoples (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993). ↩

- Tiya Miles, “Preface: Eating Out of the Same Pot?,” in Crossing Waters, Crossing Worlds: The African Diaspora in Indian Country, ed. Tiya Miles and Sharon P. Holland (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006), xv-xvi. ↩

- In the interim, the historian James Brooks, who participated in the Dartmouth conference, edited an anthology that explored comparable questions. James Brooks, ed. Confounding the Color Line: The Indian-Black Experience in North America (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002). ↩

- Tiya Miles and Sharon P. Holland, eds. Crossing Waters, Crossing Worlds: The African Diaspora in Indian Country (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006), 3, 22. ↩

- Tiffany Lethabo King, The Black Shoals: Offshore Formations of Black and Native Studies (Durham: Duke University Press, 2019). ↩

- Kyle Mays, “Indigenous Detroit: Indigeneity, Modernity, and Racial and Gender Formation in a Modern American City, 1871-2000” (PhD diss., University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2015); Mays, “Decolonial Hip Hop: Indigenous Hip Hop and the Disruption of Settler Colonialism,” Cultural Studies 33, no. 3 (2019): 460-76. ↩

- “Kyle T. Mays,” UCLA Department of African American Studies, accessed August 27, 2019, https://afam.ucla.edu/2017/08/14/kyle-mays/. ↩

- These intersecting histories are not confined to Native and African peoples in the British colonies. See Dedra S. McDonald, “Intimacy and Empire: Indian-African Interaction in Spanish Colonial New Mexico, 1500-1800,” in Confounding the Color Line: The Indian-Black Experience in North America, ed. James Brooks (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002), 21-46. ↩

- Celia Naylor, African Cherokees in Indian Territory: From Chattel to Citizens (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008), 22. See also Tiya Miles, Ties that Bind: The Story of an Afro-Cherokee Family in Slavery and Freedom (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005); and Tiya Miles, The House on Diamond Hill: A Cherokee Plantation Story (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010). ↩

- David Chang, The Color of the Land: Race, Nation, and the Politics of Landownership in Oklahoma, 1832-1929 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010). See also Kendra Taira Field, Growing Up with the Country: Family, Race, and Nation after the Civil War (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018). ↩

- David Chang, “Where Will the Nation Be at Home?: Race, Nationalisms, and Emigration Movements in the Creek Nation,” in Crossing Waters, Crossing Worlds: The African Diaspora in Indian Country, ed. Tiya Miles and Sharon P. Holland (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006), 80. ↩

- Alaina Roberts, “A Hammer and a Mirror: Tribal Disenrollment and Scholarly Responsibility,” Western Historical Quarterly 49, no. 1 (2017): 92. ↩

- Roberts, “A Hammer and a Mirror,” 91. ↩

- Roberts, “A Hammer and a Mirror.” ↩

- Jodi Byrd, The Transit of Empire: Indigenous Critiques of Colonialism (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011), 146. ↩

- Quoted in Byrd, The Transit of Empire, 146. ↩

- Byrd, The Transit of Empire, xix. ↩

- Kyle Mays, “The Political Discourse of Black Indigeneity, and Why It Matters,” Native Appropriations, June 16, 2015, http://nativeappropriations.com/2015/06/the-political-discourses-of-black-indigeneity-and-why-it-matters.html; and Mays, “Black Indigeneity, Part II (Or Back to Back),” Native Appropriations, January 25, 2016, https://nativeappropriations.com/2016/01/black-indigeneity-part-ii-or-back-to-back.html. See also Mays, “Indigenous Genocide and Black Liberation,” Indian Country Today, February 24, 2017, https://newsmaven.io/indiancountrytoday/archive/indigenous-genocide-and-black-liberation-mYZF-Vjd3U-eKD5JSX-ERg/. Grace Lee Boggs was the child of Chinese immigrants. ↩

- Thomas Sugrue’s history of postwar Detroit refers to an active Black “Pioneers Club” in the 1950s. Sugrue uses the phrase “black pioneers” throughout the monograph. Sugrue, The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005), 235. ↩

- Miles, Ties that Bind, 4-5. ↩

- Kyle Mays, “Transnational Progressivism: African Americans, Native Americans, and the Universal Races Conference of 1911,” American Indian Quarterly 37, no. 3 (2013): 243. ↩

- Vine Deloria Jr., Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto (New York: Macmillan, 1969). ↩

- Robert Warrior, “Afterword,” in Crossing Waters, Crossing Worlds: The African Diaspora in Indian Country, ed. Tiya Miles and Sharon P. Holland (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006), 321-25. For other reflections on the emotional as well as intellectual dynamics of the conference, see Miles, “Preface: Eating Out of the Same Pot?”; and Valerie J. Phillips, “Epilogue: Seeing Each Other through the White Man’s Eyes,” in Confounding the Color Line: The Indian-Black Experience in North America, ed. James Brooks (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002), 371-85. ↩

- King, The Black Shoals, x, xiii. ↩