Introduction / Issue 31: Black Studies Now and the Countercurrents of Hazel Carby

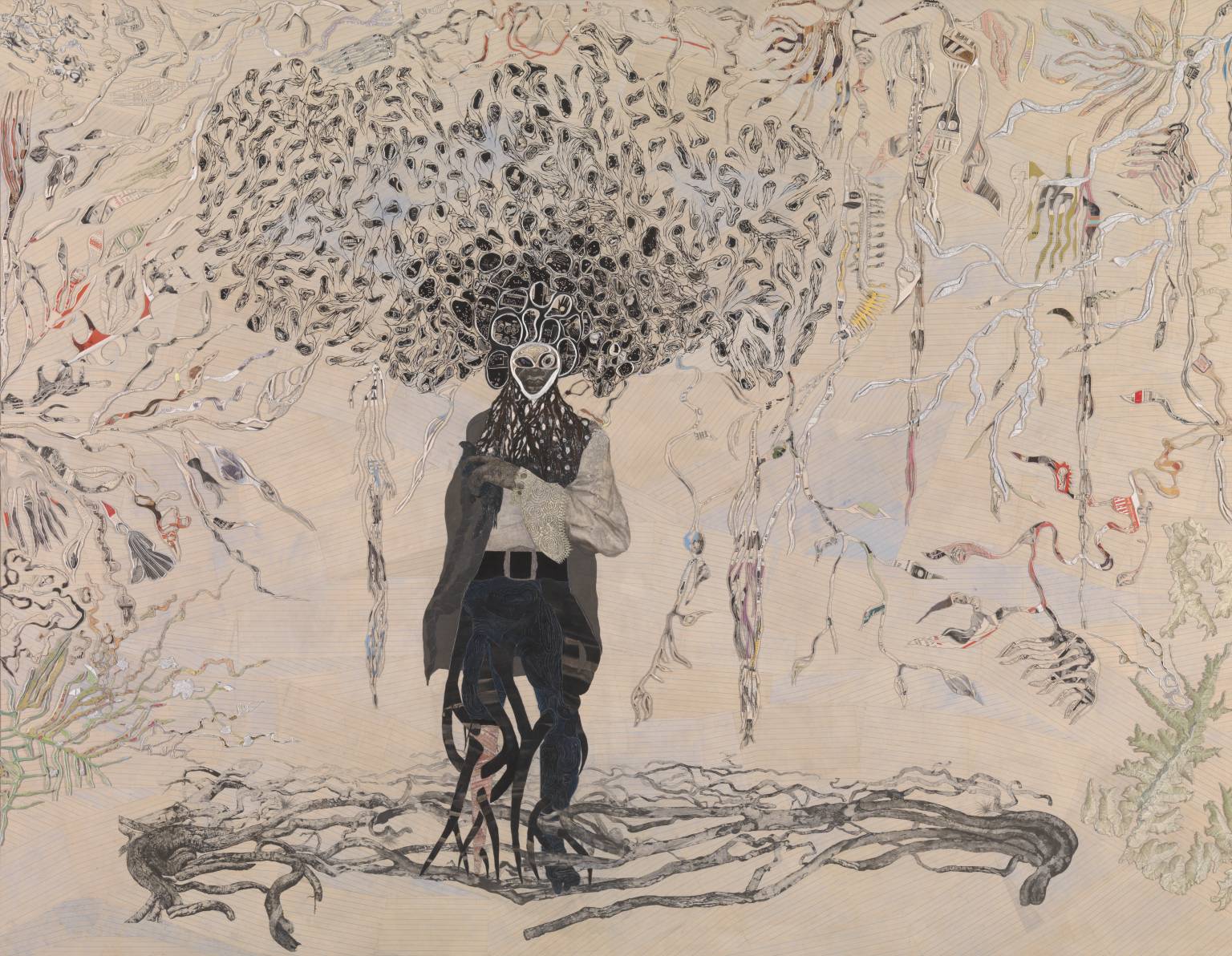

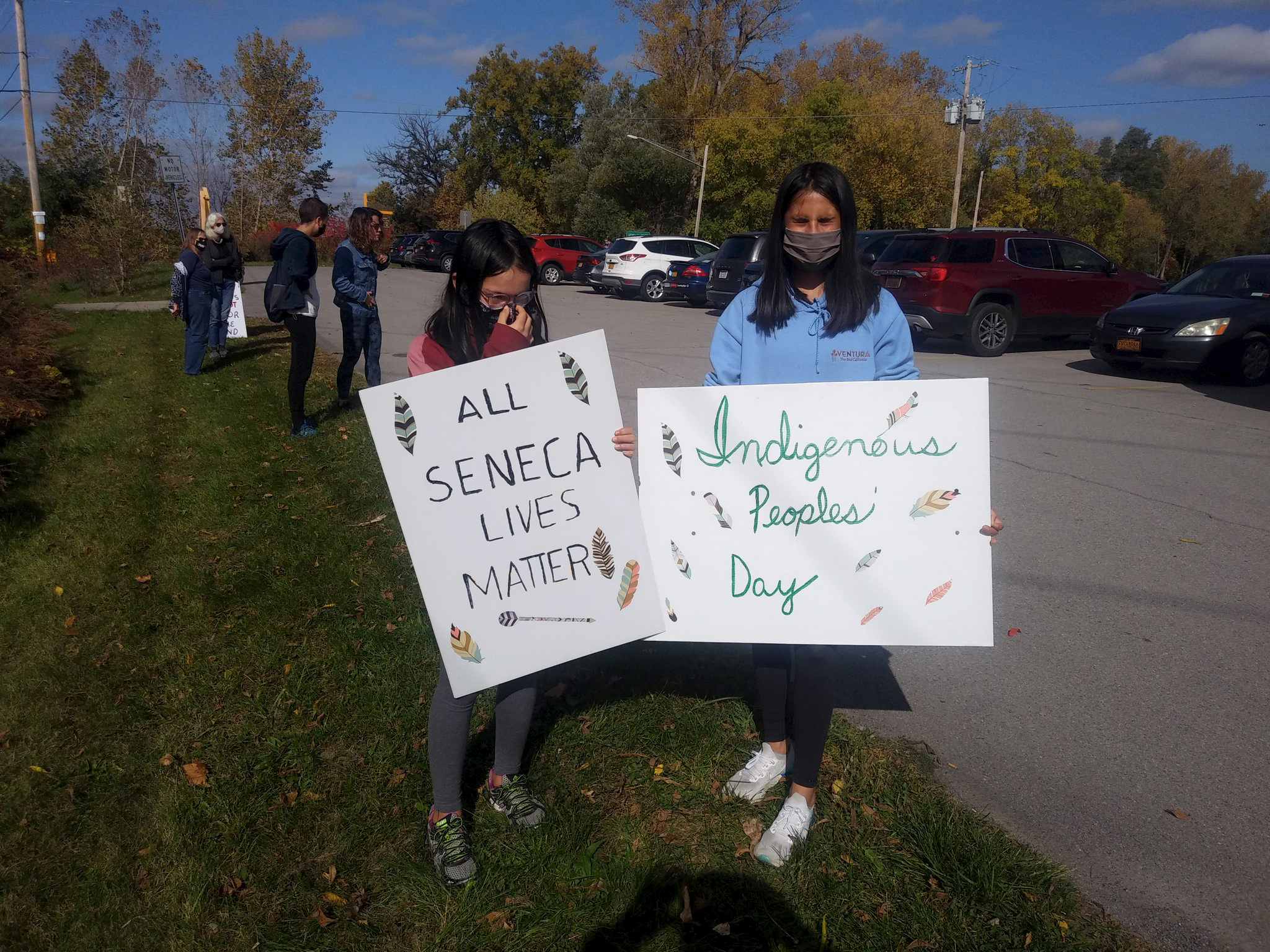

Jump to Table of Contents by Joel Burges, Alisa V. Prince, and Jeffrey Allen Tucker Featured image: Ellen Gallagher, Bird in Hand, 2006. © Ellen Gallagher. Image © Tate. She was dismayed when she realized that what she wanted to imagine, what she was struggling to bring into being, now seemed beyond her reach. Was it improbable or impossible? What could she dream in a present of imminent environmental catastrophe? How could she sculpt the contours of a future when the future, any future, had been foreclosed?—Hazel V. Carby, “Black Futurities: Shape-Shifting beyond the Limits of the Human”1 In winter 2019, when Hazel V. Carby came to the University of Rochester (UR) as the Distinguished Visiting Humanist, no one knew global pandemic and large-scale anti-racist protests awaited us one year later in the spring, summer, and now fall of 2020.2 We did not anticipate the rise of an anti-immigrant visa crisis in higher education as we began to write this introductory essay, or the revelation of the death of Daniel Prude as we were finalizing …