Introduction

Google has become a central object of study for digital media scholars due to the power and impact wielded by the necessity to begin most engagements with social media via a search process, and the near-universality with which Google has been adopted and embedded into all aspects of the digital media landscape to respond to that need.1 Therefore, the near-ubiquitous use of search engines, and Google, in particular, in the United States demands a closer inspection of what values are assigned to race and gender in classification and web indexing systems and the search results they return. It also calls for explorations into the source of these kinds of representations and how they came to be so fundamental to the classification of human beings. In this research, I am interested in knowing two things: what kinds of results do Google’s search engine provide about Black girls when keyword searching, and what do the results mean in historical and social contexts? I also want to know in what ways does Google reinforce hegemonic narratives. To answer these questions, I use Critical Discourse Analysis as a method to explore the ways that Google Search results on the words “Black girls” discursively reflect hegemonic social power and racist and sexist bias. This research points toward a type of cultural hegemony within Google’s results on racialized and gendered identities, which prioritize the interests of its commercial partners and advertisers, rather than rendering the social, political and economic interests of Black women and girls visible.2

It is dominant narratives about the objectivity and popularity of web search results that make misogynist or racist search results appear to be natural. Not only do they seem “normal” due to the technological blind spots of users who are unable to see the commercial interests operating in the background of search (deliberately obfuscated from their view), they also seem completely unavoidable because of the perceived “popularity” of sites as the factor that lifts websites to the top of the results’ pile. Furthermore, general belief in myths of digital democracy emblematized in Google and its search results means that users of Google give consent to the algorithms’ legitimacy through their continued use of the product, despite its ineffective inclusion of websites that are decontextualized from social meaning, and Google’s wholesale abandonment of responsibility for its search results.3

To start revealing some of the processes involved, it is important to think about how results appear. Although one might believe that a query into a search engine will produce the most relevant and therefore useful information, it is actually predicated upon a matrix of ways in which pages are hyperlinked and indexed on the web, which has been carefully detailed by Mark Levene.4 Rendering web content (pages) findable via search engines is an expressly social, economic, and human project5—in which this goal is turned into a set of steps (algorithm) implemented by programming code, and then naturalized as “objective.” This process is algorithmic, scientific and mathematical by virtue of the procedural and mechanistic practices of tracing links among pages and legitimated as a process of “voting.”6 For the most part, many of these processes have been automated or they happen through Graphical User Interfaces (GUIs) that allow people who are not programmers (i.e. not working at the level of coding) to engage in sharing links to and from websites.

Research shows that users typically use very few search terms when seeking information in a search engine and rarely use Advanced Search queries, as most queries are different from traditional offline information seeking behavior.7 This front-end behavior of users appears to be simplistic. However, the information retrieval systems are complex, and the formulation of users’ queries involves cognitive and emotional processes that are not necessarily reflected in the system design.8 In essence, while users use the most simple queries they can in a search box because of the way interfaces are designed, this does not always reflect how search terms are mapped against more complex thought patterns and concepts that users have about a topic. This disjunction between, user queries and their real questions on the one hand, and information retrieval systems on the other, makes understanding the complex linkages between the content of the results that appear in a search, and their import as expressions of power and social relations of critical importance. Additionally, the public generally trusts information found in search engines. Yet, much of the content surfaced in a web search in a commercial search engine is linked to paid advertising, in part, which helps drive it to the top of the page rank,9 and searchers are not typically clear about the distinctions between “real” information and advertising.

Racial and gender bias in Google search

Search is one of the most under-examined aspects of power and consumer protections online, and regulation in the provision of information to the public through the Internet.10 I contend that there is value in expanding the discourse about search engine results by examining its intersecting racial and gendered bias. By taking a deep look at a snapshot of the web, at a specific moment in time and interpreting the results against the history of race in U.S. society, there is an opportunity to make visible processes that are biased in their impact, but obscured through the rhetoric of technology’s neutrality and popular acceptance in being merely a tool for human use. Therefore, this study is theoretically concerned with using critical race theory11 and Black feminism,12 to examine the commercial co-optation of keywords on Black identity. Google and other information monopolies like it have the ability to prioritize web search results based on a variety of interests.13 In this case, the clicks of users coupled with the commercial processes that allow paid advertising to be prioritized in search results mean that representations of women (particularly Black women who are codified as “girls”) are frequently ranked on a search engine page in ways that underscore their lack of status in society. Although I have collected searches on many racialized and gendered identities in the United States, the scope of this article is limited to a discussion of a search on “Black girls.” Certainly, there are many misrepresentations of identity in commercial search, and comparisons and critical analysis of these identities will be the subject of future research. Searches on girls of color, as demonstrated by the specific discussion of Black girls, show the ways in which membership in gendered and racialized groups is highly sexualized and even stigmatized. This is not unlike the ways in which men, boys and Whites are characterized or represented, as even these are not without challenge due to lack of historical and social context for the nuances and importance of identity. My research is focused on leveraging the knowledge stemming from the digital humanities and social sciences to improve upon how identity information is portrayed in search engines, free from commercial influence, constraint and co-optation. Moreover, and this close reading of Black girls is intended to inform our recognition that there are problems with the way in which community based identities are unprotected and continually subject to the influence of commercialization.

Google’s algorithmic practices of biasing information toward the interests of the powerful elites in the United States,14 while at the same time presenting its results as generated from objective factors has resulted in a provision of information that perpetuates the characterizations of women and girls through misogynist and pornified websites. Stated another way, it can be argued that Google functions in the interests of its most influential (i.e. moneyed) advertisers or through an intersection of popular and commercial interests. Yet Google’s users think of it as a public resource, generally free from commercial interest15—this fact likely bolstered by Google’s own posturing as a company for whom the informal mantra, “Don’t be evil,” has functioned as its motivational core.

Further complicating the ability to contextualize Google’s results is the power of its social hegemony.16 At the heart of the public’s general understanding and trust in commercial search engines like Google, is a belief in the neutrality of technology—a technologically deterministic blind spot to the embedded social values in technology design itself—which only obscures our ability to understand the potency of misrepresentation that further marginalizes and renders the interests of Black women, coded as girls, invisible. On its own, commercial search does not provide appropriate social, historical, and contextual meaning to those who historically have been portrayed in racialized and hyper-sexualized ways. In this study, the reader will find a more meaningful understanding of the kind of harm that such limitations can cause for users reliant upon the web as an artifact of both formal and informal culture.17

Online racial disparities cannot be ignored in search because it is part of the organizing logic within which information communication technologies proliferate, and the Internet is both reproducing social relations and creating new forms of relations based on our engagement with it. Search technologies themselves and their design do not dictate racial ideologies; rather, they both reflect and re-instantiate the current social climate and prevailing social and cultural values. As users engage with technologies like search engines, they dynamically co-construct content within the technology itself.18 For example, clicking on links and hyperlinking websites together is one way of affecting search results—but only one. Results are partially a matter of algorithms, which include the ways that users have engaged with sites in the past. Online information and content available in search is also structured systemically by the infusion of advertising revenue and the surveillance of user searches, over which the subjects of such practices have very little ability to reshape or reformulate.

Hyper-visibility as a Means of Rendering Black Women and Girls Invisible Online

The potency of Google is that it functions as the dominant “symbol system” of society due to its prominence as the most popular search engine to date, and through its market dominance.19 Yet, rather than find access to empowerment on the first page of search, we find another site of struggle. The narrative of Black girls as pornographic object diminishes the prioritization of feminist knowledge and information in commercial search.

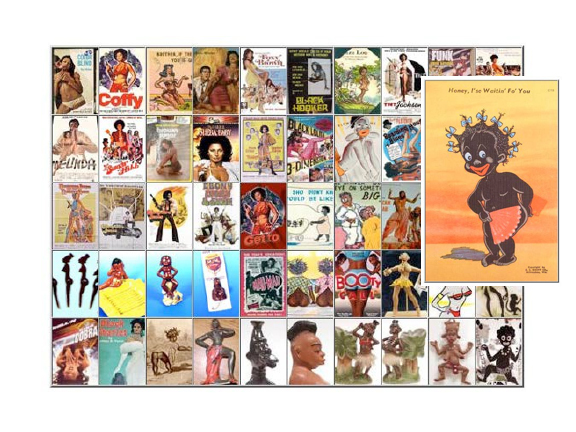

Black Feminist scholars are increasingly looking at how Black women are portrayed in the media across a host of stereotypes, including pornography, and I am adding to this tradition by looking at the web.20 Jennifer C. Nash foregrounds the complexities of Black women and pornography in ways that are helpful by theorizing that the ways in which Black women are sexualized is contingent upon racist narratives, which are both historical and profitable.21 As a result, Black feminists have typically aligned with anti-pornography rhetoric and scholarship to respond to this phenomenon.22 While this research is not a specific study in the nuances of Black women’s agency in Internet pornography, which Mireille Miller-Young has covered in detail, or the virtues and problematics of pornography;23 in general, this literature is helpful in explaining how women are displayed as pornographic search results. I therefore integrate Nash’s expanded views about racial iconography into a Black feminist visual studies framework to help interpret and evaluate the Google search results.24 These iconic representations can be seen over time in Fig. 1.

Figure 1. One dominant narrative stereotype of Black women: The Jezebel Whore, depicted in more than 100 years of cultural artifacts. Source: Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia at Ferris State University.

It is important then to locate the current online narratives in historical and social context, which I believe reflect the furthering of hegemonic, dominant narratives of Black women as hypersexualized and oversexed, and serve as a silencing mechanism in the efforts to gain greater social, political, and economic agency. Specifically, cultural images and symbols inject dominant social biases into search engine results by transmitting a coherent set of meanings that evolve historically. By foregrounding pornography as the most important or meaningful kind of information about Black women, as Google did in the 2011 rankings I have examined, these narratives are made most meaningful.

In the field of Internet and media studies, much of the research interest and concern of scholars about harm in imagery and content online has been framed around the social and technical aspects of addressing Internet pornography, but less so about the existence of commercial porn, which is a less desirable subject of study.25 As a result, Black women and girls are both under-studied by scholars and associated with “low culture” forms of representation.26 This blind spot in research is directly linked to the positionality of Black women and women of color as less suitable subjects of inquiry in scholarly publishing, in general.

The porn industry was valued at $96 billion in 2006 and encompasses an estimated 420 million pages of porn on the Internet, 4.2 million websites dedicated to porn, and 68 million search engine requests for porn every day.27 There is a robust political economy of pornography, which is an important site of commerce and technological innovation that includes file sharing networks, video streaming, e-commerce and payment processing, data compression, search, and transmission.28 Gail Dines discusses this web of relations that she characterizes as stretching “from the backstreet to Wall Street.”29 Black women are more racialized and stereotyped in pornography—explicitly playing off of the media misrepresentations of the past, and leveraging the notion of the Black woman as “ho” through the most graphic types of porn in the genre. Miller-Young underscores the fetishization of Black women that has created new markets for porn, explicitly linking the racialization of Black women in the genre, as evidenced in the kinds of representations Google surfaced to the top.30

Women’s bodies serve as the site of sexual exploitation and representation under patriarchy, but Black women serve specifically as the deviant of sexuality when mapped in opposition to White women’s bodies.31 Identities of Black women and black girls are a profitable site of taboo sexuality32 and are positioned as a type of “truth” based on public trust in the credibility of Google search.33 bell hooks details the ways that Black women’s representations are often pornified by White and patriarchally-controlled media, and that, while some women are able to resist and struggle against these violent depictions of Black women, others co-opt these exploitative vehicles and expand upon them as a site of personal profit.34 Miller-Young’s research on the political economy of pornography is important to understanding how Black women are commodified through the “‘pornification’ of hip-hop and the mainstreaming and ‘diversification’ of pornography.”35

The web itself has opened up new centers of profit and pushed the boundaries of consumption. Never before have there been so many points for the transmission and consumption of these representations of Black women’s bodies. It is in this tradition, then, that studying the discursive realm of text, image, and meaning prioritized in web search can be beneficial to studying race and gender on the Internet. This, coupled with the advertising costs associated with racial and gender identities brokered by Google can help make sense of the trends that make Black women and girls’ sexualized bodies a lucrative marketplace on the web. In this case, I contextualize porn on the Internet as an expansion of capitalist interests.

The Reproduction of Racialized and Gendered Power Relations

Noticeably absent in the discussions of Google’s near-monopoly status is the broader, social and technical interplay that exists dynamically in how technology is increasingly mediating public access to information, from libraries to the search engine. Lack of attention to the current exploitative nature of online keyword searches only further entrenches the problematic misrepresentations in the media for women of color, since the Internet and its landscape offer up and eclipse traditional media distribution channels, and serve as a new infrastructure for delivering all forms of prior media: television, film, and radio, as well as new media which are more social and interactive. Taking these old and new media together, it can be argued, as Jessica L. Davis and Oscar H. Gandy do, that the Internet has significant influence on forming opinions on race and gender.36 Representations of women and people of color in the traditional mass media, akin to those I discuss here in search results, have been problematized by many scholars37 and the Internet is part of the landscape of new media where race and representation are being investigated.38 Despite the rhetoric of freedom, and the contradictions that Wendy Chun articulates in her work on how the Internet has been sold as a source of freedom,39 the reorganization of economic and social relations in the shift from the industrial to “information society” has led to even more uneven distributions of capital around the globe and a reconstitution of social and economic relations predicated upon “information haves and have nots.”40 What this analysis underscores is that biased traditional media processes are being replicated, if not more aggressively, around Black girls (and women’s) misrepresentations in search. This is important because the web has been embraced as a liberating tool in the age of digital technology. Information, knowledge, and culture are central to human freedom and human development. How these are produced and exchanged in our society critically affects the way we see the state of the world as it is and might be; who decides these questions; and how we, as societies and polities, come to understand what can and ought to be done.41

In fact, many aspects of these uneven distributions of power are predicated upon racialized and gendered practices—from extraction practices in the making of microchip processors, to computer hardware manufacturing through the disposal of e-waste. These practices are often hidden from view and rendered invisible. Sarah T. Roberts’ research underscores, for example, the various hidden aspects of digital labor that are often racialized and gendered in video content moderation—a key service used by giant media companies like Facebook or Google’s subsidiary, YouTube.42 She notes that practices of determining which kind of content (video) is allowed to proliferate in online commercial spaces, which:

…introduces the existence of actors unknown to and unseen by the vast majority of end-users who are nevertheless critical in the production chain of social media-making decisions… It paints a disturbing view of an unpleasant work task that the existence of social media and the commercial, regulated Internet, in general, necessitate.43

These labor pools are often racialized and gendered, as are the values upon which moderation takes place. What this work underscores are the myriad ways that decision-making processes are happening within the platform, via both human and algorithmic protocols and other human interventions.

Roberts’s research intersects the findings of this study by pointing to how the results that surface on the web in commercial spaces like Google are not neutral processes—they are linked to human experiences, decision-making, and culture. Amidst a host of complaints about the lack of transparency in Google’s search technology, the company released an infographic in early 2013 on how its algorithm works.44 The company explained that it currently indexes over 30 trillion web pages through hyperlinks, sorts the content based on more than 200 factors, and filters out spam to ensure high quality information is provided in its search technology. What is important about this latest information release from Google is its acknowledgement that its employees make programs and algorithms in “The Search Lab” and that the ideas for search are a product not of the algorithm on its own (as it suggests in its explanation for why we get objectionable content on some searches45) but as a product of its engineers.

Search is Not Democratic for Black Women and Girls

There are many myths about Internet search engines that proliferate, including the notion that what rises to the top of the information pile is strictly what is most popular as indicated by hyperlinking. Indeed, what is most popular on the web is not necessarily what is most trustworthy or truthful. It is on this basis I contend there is work to be done to contextualize and reveal the many ways that Black women are framed in sexist language that renders them “girls” and misrepresented commercial search. This warrants an exploration into the complexities of whether the content surfaced is a result of popularity, credibility, commerciality—or even a combination thereof. Borrowing from Matthew S. Hindman’s critique of the flawed logic that web results are the result of democratic processes (e.g., we vote with our clicks and only what is most popular rises to the top),46 the outcome of the searches I studied in 2011 would suggest that both sexism and pornography were, at that time, the most “popular” values on the Internet when it came to women, especially Black women and Black female children. In reality, there is more to result-ranking than just how we vote with our clicks47 and various expressions of sexism and racism are related, as my research shows.

At the time this study was conducted, Google had not yet launched its new “personalization” tools which are designed to incorporate past search histories and help shape and tailor search results based on past places that have been visited online, so it is important to understand how this new protocol by Google might impact future results. A 2011 study by Martin Feuz, Matthew Fuller, and Felix Stalder found that personalization is not simply a service to users, but rather a mechanism for better matching consumers with advertisers, and that Google’s personalization or aggregation is about actively matching people to groups; that is, categorizing individuals.48 Personalization is, to some degree, giving people the results they want based on what Google knows about its users, but it is also generating results for viewers to see that Google calculates might be good for its advertisers. As a result of these practices, increasing attention is being paid to how the Internet acts as the space within which the attention, desires, and free labor of users are harnessed into surplus value.49 This new wave of digital interactivity, and its blind spots, is on the minds of many critical communications scholars, and has been an extensive site of inquiry about labor and the digital age.50

Not only do search engines often track and remember the digital traces of where we have been and what links we have clicked in order to provide more custom content (a practice that has begun to gather more public attention after Google announced it would use past search practices and link them to users in its privacy policy change in 201251), but search results also vary depending on whether filters to screen out pornography are enabled on computers. Information that surfaces to the top of the search pile is not exactly the same for every user in every location, and a variety of commercial advertising, political, social, and economic decisions are linked to the way search results are coded and displayed. At the same time, results are generally quite similar, and complete search personalization—customized to very specific identities, wants and desires—had yet to be developed in 2011. Personal-identity personalization has less impact on a variation in results than generally believed by the public.52

Understanding Identity Online

This research focuses on the capture of search results at one moment in time, and I use Critical Discourse Analysis as a method to make sense of what it means to get such results. Although I am focusing on Black women and girls, I try to resist the notion of essentializing the racial and gender binaries; however, I do acknowledge that the discursive existence of these categories, “Black” and “women/girls,” is shaped in part by power relations in the United States that tend to essentialize and reify such categories. Thomas Nakayama and Robert Krizek discuss the possibilities for understanding how racial identities are constructed and otherized in relation to largely under-examined sites of White identity.53 In seeking this object of analysis, I am actively engaging in an effort to unveil the hegemonic ways in which intersecting racialized and gendered identities are portrayed and legitimated through Google search. André Brock adds that “the rhetorical narrative of ‘Whiteness as normality’ configures information technologies and software designs” and is reproduced through digital technologies.54 Thus, hegemonic discourses about the hypersexualized Black woman, which exist offline in traditional media, are instantiated online as evidenced by my discussion of search results in Google.

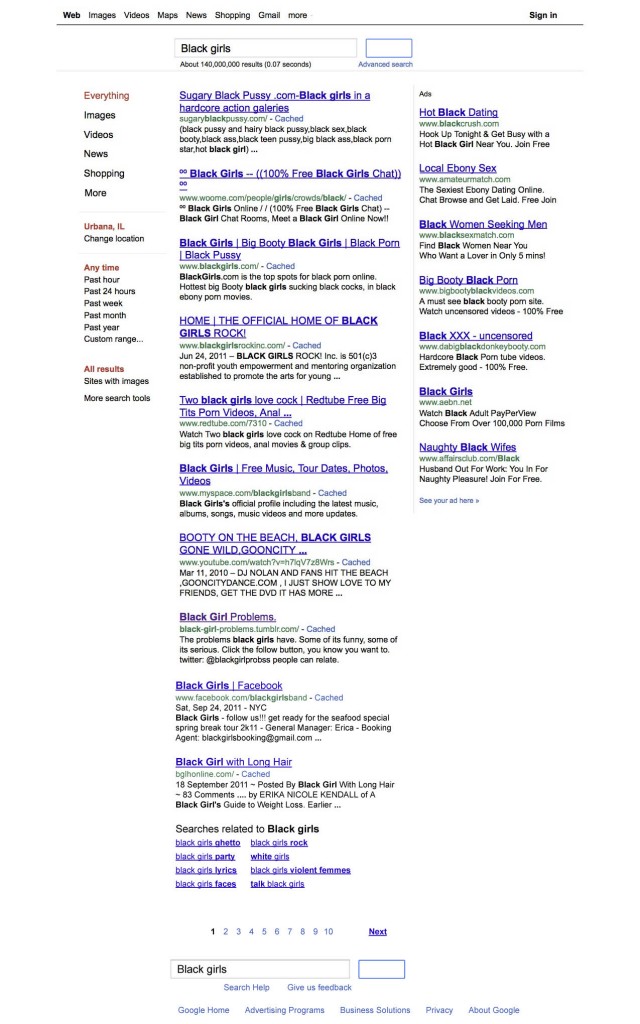

The following screen shot [Fig. 2] was captured on September 18, 2011 and reflects the way in which results were prioritized from Google’s indexed pages on the web:

In Fig. 2, Black girls are sexualized or pornified in half (50%) of the first ten results on the keyword search “Black girls.” Only three of ten results (30%) are blogs focused on aspects of social or cultural life for Black women and girls. One of the first ten results is a U.K. music band comprised of White men, and is coded as non-racial and non-gendered.

What these results point to is the commodified nature of Black women’s bodies on the web—and the little agency that Black female children (girls) have had in securing non-pornified narratives and ideations about their identities on the first page of search engine results. These results can be thought of as a visible representation of the ways in which Black girls as a sector of society are represented on any given day in Google’s search process. It is plausible at any given moment under the current search engine mechanism at play that other results might be prioritized. In fact, a year prior to this search, in 2010, the website www.hotblackpussy.com was the first result in a search on the term “Black girls.” By the end of 2012, Google’s algorithm had changed or search optimization techniques had been employed and the results had shifted to www.blackgirlsareeasy.com. As these results shift over time, what is clear is that the relationship between advertising and keywords, and that there is a lack of broader agency that exists at the abstracted level of community or group for women to influence their pornified representations.

A Critical Approach to Search

This raises questions about who owns identity and identity markers in cyberspace, and whether racialized and gendered identities are ownable property rights that can be contested in cyberspace. One can argue, as I am, that social identity is both a process of individual actors participating in the creation of identity, but also a matter of social categorization that happens at a socio-structural level and as a matter of personal definition and external definition.55 According to Mary Herring, Thomas B. Jankowski and Ronald E. Brown, Black identity is defined by an individual’s experience of common fate with others in the same group.56 The questions of specific property rights to naming and owning content in cyberspace are an important topic.57 I argue that racial markers are a social categorization that is both imposed and adopted by groups.58 Thus, racial identity terms could be claimed as the property of such groups, much the way Whiteness has been constituted as a property right for those who possess it.59 This is a way of thinking about how mass media has co-opted the external definitions of identity60—racialization —which also applies to the Internet and its provision of information to the public:

Our relationships with the mass media are at least partly determined by the perceived utility of the information we gather from them… Media representations play an important role in informing the ways in which we understand social, cultural, ethnic, and racial difference.61

Davis and Gandy argue that media have a tremendous impact on informing our understandings of race and racialized others as an externality—but this is a symbiotic process that includes internal definitions that allow people to lay claim to racial identity.62 Critical Race Theory and critical discourse analysis allows for a deeper reading of what it means for identity to be in the dialectical tension between the struggles for social justice organized around collective identities and histories, and the commercialization of such identities to sell products, services, and ideologies in an effort to accumulate greater profits.

Using Critical Race Theory as a framework for implementing Norman Fairclough’s critical discourse analysis means that I focus on the signifiers that make up a text, the specific linguistic selections that are apparent, the way in which they are juxtaposed, the sequencing and layout on the page and so on.63 According to Fairclough, the study of texts and images and the discursive ways they are used to represent people is important because it has direct impact on what the receptive public believes.64 Images and the visual culture in the United States are critical to the shaping of identity. This is not to say that people do not have agency in re-shaping and re-constituting identity through texts, institutions, organizations, political action, and other such engagements. However, what Fairclough stresses is the causal effect of visual texts on belief—as they “contribute to establishing, maintaining and changing social relations of power, domination and exploitation.”65 This critical view on ideology is a fundamental part of understanding how to evaluate texts and images beyond the descriptive content analysis methods that can report the kinds of words that appear in a URL, sentence description, or advertisement, but fall short of being contextualized in terms of power or domination among various social groups.66 Moreover, Mikhail Bakhtin elucidates this idea that “utterances” are deeply embedded in specific cultural contexts:

The linguistic significance of a given utterance is understood against the background of language, while its actual meaning is understood against the background of other concrete utterances on the same theme, a background made up of contradictory opinions, points of view and value judgments—that is precisely that background that, as we see, complicates the path of any word toward its object.67

Indeed, the text and images on a web page also constitute “utterances” in the Bakhtinian sense, and they operate and are positioned in a deeper context of racist and sexist cultural representations and mischaracterizations of Black women and children over the course of centuries.

By comparing the results and ads on the search for “Black girls” to broader social narratives about Black women and girls in the dominant U.S. popular culture, we can see the ways in which search engine technology replicates and instantiates derogatory notions. These discourses include narratives of Black women as a series of historical and modern stereotypes such as “Jezebel,” “Sapphire” and the “Mammy,”68 which are often met with resistance by Black women and girls, and simultaneously, woefully internalized.69 During slavery, stereotypes were used to justify the sexual victimization of Black women by their property owners, given that under the law, Black women were property and therefore could not be considered victims of rape. Manufacture of the Jezebel stereotype served an important role in portraying Black women as sexually insatiable and gratuitous.70

Understanding the power relations embedded in texts includes examining the actors involved. In the case of looking at Internet search, I concede that there are a number of actors and artifacts: the producers of websites, the words or text chosen for the URL, sentence descriptions and advertisements, search engine algorithms and optimizers, media conglomerates, advertisers, and search engine users who come across search results—all of which are involved in the production of meaning.71 Published text and images on the web can have a plethora of meanings, so attention must be paid to the implicit and explicit messages about Black women as girls in both the texts of Internet search results or hits and the paid ads that accompany them on the web page.

Analyzing Discursive Representations: Black Girls as Commodity Objects

There are theoretical ways to contextualize and analyze what it means to be characterized through texts and images and how this is an expression of power relations. Michel Foucault offers a meaningful way to think about the ways that discourse is located in “external conditions of existence, for that which gives rise to the chance series of these events and fixes its limits.”72 The pornification of identity, or its co-optation by industries that can profit from it, are given rise from the current conditions upon which information access on the web is largely a commercial venture in search. The conditions of Black women identities (as girls) are also conditioned by the long history of media misrepresentation. Therefore, in my analysis of search results, I do not look deeply at what advertisers or Google may be intending to do. Instead, I focus on the social conditions that surround the lives of Black people as they have been affected by conditions that allow such representations to come to the fore. In order to more fully comprehend the Foucauldian call for an examination of the “external conditions of existence,”73 Barney Warf and John Grimes explore the counter-hegemonic discourses of the Internet by noting the stable hegemonic notions of the web, which have persisted, and are part of the external logic that buttresses and obscures social aspects of the web:

Much of the Internet’s use, for commercialism, academic, and military purposes, reinforces entrenched ideologies of individualism and a definition of the self through consumption. Many uses revolve around simple entertainment, personal communication, and other ostensibly apolitical purposes… particularly advertising and shopping but also purchasing and marketing, in addition to uses by public agencies that legitimate and sustain existing ideologies and politics as “normal,” “necessary,” or “natural.” Because most users view themselves, and their uses of the Net, as apolitical, hegemonic discourses tend to be reproduced unintentionally…Whatever blatant perspectives mired in racism, sexism, or other equally unpalatable ideologies pervade society at large, they are carried into, and reproduced within, cyberspace.74

One way of evaluating the quality of Google’s search results on identity is to try to make sense of identity markers and the results found in search against what Foucault might characterize as part of the logic of the web. Brock characterizes these transgressive practices that couple technology design and practice with racial ideologies “as a social structure, represents and maintains White, masculine, bourgeois, heterosexual and Christian culture through its content…. These practices neatly recreate social dynamics online that mirror offline patterns of racial interaction by marginalizing women and people of color.”75 What Brock points to is the way in which discourses about technology are explicitly linked to racial and gender identity—normalizing Whiteness and maleness in the domain of digital technology and as a presupposition for the prioritization of resources, content, and even the design of information and communication technologies.

I use Fairclough’s critical discourse analysis model, which involves text analysis (description), processing analysis (interpretation) and social analysis (explanation). I looked at the page of search results and I clicked on the links to understand more deeply the content that these headlines, URLs and sentences are describing:

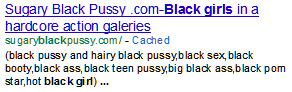

Figure 3. First result on the first page of a keyword search for Black girls in Google search engine on 09/18/11.

In the text for the first result [Fig. 3], the word “pussy,” as a noun, is used four (4) times to describe Black girls. This necessitates an examination of the process by which the search result is being produced and received. Another way of processing meaning and interpreting the text as described above is to click on the links to see if the content of the site being described is accurately reflected in the description, URL and headline:

Figure 4. First page (partial) of results on Black girls in a Google Search with first result detail and advertising.

In the case of the first page of results on Black girls, I clicked on the link for both the top search result (unpaid) and the first paid result, reflected on the right hand side bar, where advertisers who are willing to spend money through Google AdWords™ are able to have their content appear in relationship to these search queries [Fig. 4].76 The advertising in relationship to Black girls is hyper-sexualized and pornographic, even if it feigns to be dating or social in nature. Additionally, some of the results like the U.K. rock band “Black Girls” lack any relationship to Black girls. This is an interesting co-optation of identity, and because of their fan following and possible search engine optimization strategies, they are able to secure strong placement for the band’s fan site on the front page of Google.

What I am arguing is that it does not matter if searches for Black girls and porn are highly popular, because a search on Black girls without including the word porn still gets you porn. Because we cannot see Google’s algorithm to understand precisely why Black girls and porn are linked, without including the term “porn” in the search, I am calling attention to what the output is (the results), regardless of whether Google was intending a shortcut because of the popularity of searching for Black girls (like many other women and girls’ identities), in 2011. Further, if all the Black girls were involved in looking for themselves using the myth of digital democracy, they would still be outnumbered by porn searchers. Thus, their identity is subject to control by people looking for porn, and porn searches do not even have to be explicit. It is precisely this shortcut, if you will, of making porn and Black girls synonymous that I am trying to point to as problematic for many women’s identities. I use the search for Black girls, in this study, as an example that boldly illustrates the point. Make no mistake, however, there are many identities that are grossly misrepresented in commercial search.

Co-optation of identity has been discussed in broad terms for many individuals and communities alike. As such, practices like “Google-bombing” (also known as Google-washing), where people co-opt contents or terms and redirect them to unrelated content, are impacting both SEO (Search Engine Optimization) companies and Google alike.77 While Google is invested in maintaining quality of search results in PageRank™ and policing companies that attempt to “game the system”—as Brin and Page foreshadowed—SEO companies do not want to lose ground in pushing their clients or their brands up in PageRank™.78 Google-bombing is the practice of excessively hyperlinking to a website to cause it to rise to the top of PageRank™, but it is also seen as a type of “hit and run” activity that can deliberately co-opt terms and identities on the web for political, ideological, and satirical purposes. Bar-Ilan has studied this practice to see if the effect of forcing results to the top of PageRank™ has lasting effect on the result’s persistence, which can happen in well-orchestrated campaigns.79 A recent media spectacle of this nature is the case of Republican Senator Rick Santorum of Pennsylvania, whose website and name was associated with insults in order to drive objectionable content to the top of PageRank™.80 Others who have experienced this kind of co-optation of identity or less than desirable association of their name to an insult include former President George W. Bush and pop singer Justin Bieber.

At the level of community identity co-optation, Vaidhyanathan chronicles recent attempts by the Jewish community and Anti-Defamation League to challenge Google’s priority ranking to the first page of anti-Semitic, Holocaust-denial websites.81 So troublesome were these search results that in 2011 Google issued a statement about its search process, encouraging people to use “Jews” and “Jewish people” in their searches, rather than the seemingly pejorative term “Jew”—claiming that they can do nothing about its co-optation by White supremacist groups.82 It is important to note that Google has conceded the fact that anti-Semitism as the primary information result about Jewish people is a problem, despite its disclaimer that tries to put the onus for bad results on the searcher. Equally troubling, in November of 2009, a Google image search for Michelle Obama produced a Photoshopped image of the First Lady as a monkey. Vaidhnayatan reminds us that rather than remove the image from its database, Google again posted the disclaimer about offensive search results and skewed the algorithm to push her image further down the image rankings.

Without such limits on derogatory, racist, sexist or homophobic materials, Google allows its algorithm—which is laden with “sociopolitics”83—to stand without debate while it protests its ability to remove pages or addresses these injustices as a function of its algorithm. I offer that we must revisit the socio-historical and commercial conditions that allow for some bodies to be sold as sexual commodity while others are assumed into the role of consumer under the organizing principles of the private sector and the heterosexual male gaze. In this case, Black women coded as girls’ online identities have been put back on the auction block for sale to the highest bidders or the most technically savvy at web optimization. The narratives of neutrality and objectivity dissuade those with legitimate protests from powerfully arguing over misrepresentation—a practice that often renders them invisible in having any effective power. Under the current rhetoric of search fairness and objectivity, the seemingly neutral algorithms by Google cannot be held responsible, nor can the authors of the mathematical language of the web search tool.

When I evaluated the types of advertising on the right hand side of the page for the term “Black girls” it became apparent that these, too, were situated in the socio-historical contexts of systemic forms of racism and sexism that make plausible a space for such misrepresentation to both exist, and be legitimated. All of the ads were pornographic or hypersexual and featured Black women who appear to be adults offering sex as the product for sale. This is how we are to make sense of the results and tie them to the conditions of possibility which created them: the hypersexualization and hyper-visibility of Black girls as sex commodities renders other possibilities of Black girls representations non-existent for, “Without much exaggeration one could say that to exist is to be indexed by a search engine.”84 These conditions for such results are equally predicated upon the legacy of domination over Black people in the United States,85 the entrapments of rape culture under patriarchy,86 and the commodification of women as pornographic objects.87 Taken together, they articulate the disturbing commercial viability of Black girls as web commodities.

Color-blindness and Neutrality as a Means of Silencing

Formulations of post-racialism presume that racial disparities no longer exist, within which the color-blind ideology finds momentum.88 George Lipsitz suggests that the challenge to recognizing racial disparities and the social (and technical) structures that instantiate them is a reflection of the possessive investment in Whiteness—the inability to recognize how hegemonic ideas about race and privilege mask the ability to see real social problems.89 In the midst of the changing social and legal environment, inventions of terms and ideologies of “color-blindness” disingenuously portend a more humane and non-racist worldview alongside celebrations of “multiculturalism” and “diversity,”90 which obscure structural and social oppression in fields like computer and information sciences that are shaping technological practices.91 Despite these conventions and ideologies that attempt to obscure the salience of race in the United States, a critical look at Google search tells a different story about representation and the forms of legitimacy that are conferred upon women’s identities. What is crucial about keyword searching is that Blacks’ and women’s status offline is reflected in the constructs of the Internet. Specifically, claims that the U.S. society is moving toward greater social equality are undermined by data that show a substantive decrease in access to home ownership, education, and jobs—especially for Black Americans.92 Making race the problem of those who are racially objectified, particularly when seeking remedy from discriminatory practices, obscures the role of government and the public to solve systemic issues.93

Central to these “color-blind” ideologies is a focus on the inappropriateness of “seeing race.” In sociological terms, color-blindness precludes the use of racial information and does not distinguish any classifications or distinctions.94 Yet, despite the claims of color-blindness, research shows that those who report higher racial color-blind attitudes are more likely to be White, and more likely to condone or not be bothered by derogatory racial images viewed in online social networking sites.95 In the midst of re-energizing the effort to connect every American, and to stimulate new economic markets and innovations that the Internet and global communications infrastructures will afford, the real lives of those on the margin are being re-engineered. New terms and ideologies make a discussion about such conditions problematic, if not impossible. This rhetoric of post-racialism and colorblindness places the onus of discrimination or racism on the individual, or in the case of Google, on the algorithm. Rather than situating problems affecting racialized groups in social structures,96 those who call attention to the problems are made the problems themselves.

These explorations of web results on the first page of a Google search also reveal the default identities that are protected on the Internet or are less susceptible to marginalization, pornification, and commodification. Don Heider and Dustin Harp showed that, in the early days of the web, even though women comprised just slightly over half of Internet users, their voices and perspectives were not as loud nor did they have as much impact online as those of men.97 Their research demonstrates how some users of the Internet have more agency and can dominate the web, despite the utopian and optimistic view of the web as a socially equalizing and democratic force.98 Their research on the male gaze and pornography on the web argues, consistent with Annette Kuhn’s argument that the Internet is a communication environment that privileges the male,99 pornographic gaze, and marginalizes women as objects.100 Consistent with other forms of pornographic representations, pornography both structures and reinforces the domination of women.101

The previous articulations of the male gaze continue to apply to other forms of advertising and media—particularly on the Internet, and this research expands the conversation about the pornification of women on the web as an expression of racist and sexist hierarchies. When these images are present, White women are the norm and Black women are over-represented, while Latinas are under-represented.102 T. A. Gardner characterizes the nature of the depictions of Black women in pornography by noting, “pornography capitalizes on the underlying historical myths surrounding and oppressing people of color in this country which makes it racist.”103 These characterizations translate from old media representations to new media forms, which I have shown in this discrete artifact captured at one moment in time.

The Internet has also been a contested space where the possibility of organizing women along feminist values in cyberspace has had a long history.104 Judy Wajcman contributes a feminist framework for theorizing the ways in which information and communication technologies are posited as the domain of men, marginalizing not only the contributions of women to ICT development, but in using these narratives to further instantiate patriarchy.105 For Wajcman, men have used their control and monopoly over the domain of technology to further consolidate their social, political and economic power in society: “Instead of treating artifacts as neutral or value-free, social relations (including gender relations) are materialized in tools and techniques. Technology was seen as socially shaped, but shaped by men to the exclusion of women.”106 Equally, the rendering of people of color as non-technical, the domain of technology “belongs” to Whites, and reinforces problematic conceptions of African-Americans.107

The work of Wajcman and Anna Everett outlines the historical development of narratives about women and people of color, specifically African-Americans. Each of their projects points to the specific ways in which technological practices prioritize the interests of men and Whites. For Wajcman, “people and artifacts co-evolve, reminding us that ‘things could be otherwise,’ that technologies are not the inevitable result of the application of scientific and technological knowledge…The capacity of women users to produce new, advantageous readings of artifacts is dependent upon the broader economic and social circumstances.”108 Adding to the historical tracings that she provides about early African-American contributions to cyberspace, Everett notes that these contributions have been obscured by “colorblindness” in mainstream and scholarly media.109 Institutional relations predicated upon gender and race situate women and people of color outside of the power systems from which technology arises. Dominance is mutually constituted within technologies, and the marginalization of women and non-Whites is a byproduct of such entrenchments, design choices, and narratives about technical capabilities.110

In the face of dominant narratives of the Internet as a mechanism for progress and advancement,111 and of increased pluralism through computer mediated communications,112 both of which notions have been contested,113 I agree with previous scholars that the structural inequalities of society are being reproduced on the Internet, and that the quest for a race-, gender- and classless cyberspace could only “perpetuate and reinforce current systems of domination.”114 This includes reinforcing narratives of commercial search engines as value-free, neutral sites on the web. More than fifteen years later, the present research corroborates past concerns about uneven racial and gender power relations on the web.

Women, particularly Black women, are manifested on the Internet in search queries against the backdrop of a White male gaze that functions as a monopolistic lenses on the U.S. Internet. Group identity as invoked by keyword searches reveals this profound power differential that is reflected in contemporary U.S. social, political, and economic life. It begs the question that if the Internet is a tool for progress and advancement as has been argued by many media scholars, then, cui bono—to whose benefit is it? Tracing these historical constructions of race and gender offline provides more information about the context in which technological objects like commercial search engines function as an expression of a series of social, political, and economic relations that are often obscured in technological practices.115

Conclusion

The impetus for my work comes from theorizing Internet web search results from a Critical Race Theory and Black Feminist Perspective; which means, I ask questions about the structure and results of web searches in relationship to social justice—a standpoint that drives me to ask different questions than have been previously posed about how Google search works. This study builds on previous research that looks at the ways in which both Whiteness and racialization are a salient factor in various engagements with digital technology represented in video games,116 websites,117 virtual worlds,118 and digital media platforms.119 A Black Feminist and Critical Race Theory perspective offers an opportunity to ask questions about the quality and content of racial hierarchies and stereotyping that appear in results from commercial search engines like Google; it contextualizes them by decentering Whiteness and maleness as the lens through which results about Black women and girls are interpreted. By doing this, I am purposefully theorizing from a feminist perspective, while addressing often-overlooked aspects of race in feminist theories of technology.

In this research, I sought to critique the political economic framework and representative discourse that surround racial and gendered identities on the web. Traditional media misrepresentations have been instantiated in digital platforms like search engines, and web search itself has been interwoven into the fabric of American culture. Although rhetorics of the Information Age broadly seek to disembody users, or at least minimize the White/majority hegemonic framework and backdrop of the technological revolution, Blacks/African-Americans have embraced, modified, and contextualized technology into significantly different frameworks despite the relations of power expressed in the socio-algorithms that privilege certain representations about Blackness and gender over others (e.g., a search of “Black girls”). I believe this study can open up a dialog about radical interventions on socio-technical systems in a more thoughtful way that does not re-inscribe racist and sexist images of women. Search is, and will continue to be, contextually relevant with culture and gender leading these identity formations among people of color in the United States.

Search engine optimization strategies and budgets are rapidly increasing to sustain momentum and status for websites in Google search. David Harvey and Fairclough point to the ways that the political project of neoliberalism has created new conditions and demands upon social relations in order to open new markets—tensions I argue, in the case of search, are at the expense of certain members of society, namely, non-majority and minority populations.120 This has negative consequences for maintaining and expanding upon social, political, and economic organization around common identity-based interests–-interests not solely based on race and gender, although these are stable categories through which we can understand disparity and inequality.

In the case of Google searches conducted in 2011, there was a limited lens through which Black girls and women could be represented on the first page of Google’s search engine results, one that rendered the social, political, and economic aspects of Black women and girls’ lives largely invisible. Although the algorithm shifted the results on Black girls in August 2012, other women and girls of color including Latinas and Asians are still hypersexualized and all of these processes deserved detailed attention. These increasing trends in the unequal distribution of wealth and resources, including assets online and control over credible representative information in commercial search are contributing to a closure of public debate and a weakening of democracy. These conditions are making discussions about problematic results in commercial platforms a matter of litigation by individuals, but leave little recourse for groups of people because of the ways in which hateful speech or harm must be proven in court. Google is protected by its reliance upon corporate free speech or lack of control over search results while simultaneously expanding its economic interests. This unbridled expansion of commercial control over information and identity deserves attention, especially as identity markers like, “Black girls,” are for sale on the web to the highest bidder.

The near-ubiquitous use of search engines in the U.S. and perhaps worldwide, demands a closer inspection of what values are assigned to race and gender in classification and web indexing systems, and warrants exploration into the source of these kinds of representations and how they came to be so fundamental to the classification of human beings. Commercial search implodes when it comes to providing reliable, credible, and historically contextualized information about women and people of color, especially Black women and girls, which serves as a means of silencing Black women and girls as social and political agents. Continued study of these phenomena is an opportunity to contest the alleged neutrality of technology, while creating new opportunities for social justice and fair representation online.

- See Helen Nissenbaum and Lucas D. Introna, “Shaping the Web: Why the Politics of Search Engines Matters,” in The Internet in Public Life, ed. Verna V. Gehring (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2004), 7-27; Shiva Vaidhyanathan, The Googlization of Everything (And Why We Should Worry) (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press , 2011); Elad Segev, Google and the Digital Divide: The Bias of Online Knowledge (Oxford: Chandos Pub, 2010); Alejandro M. Diaz, “Through the Google Goggles: Sociopolitical Bias in Search Engine Design,” in Web Searching: Multidisciplinary Perspectives, eds. Amanda Spink and Michael Zimmer (Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer, 2008), 11–34. ↩

- For the concept of cultural hegemony, see Antonio Gramsci, Prison Notebooks, ed. J. A. Buttigieg (NY: Columbia University Press, 1992). ↩

- See Matthew S. Hindman, The Myth of Digital Democracy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009). ↩

- Mark Levene, An Introduction to Search Engines and Navigation (Harlow, England: Addison Wesley, 2006). ↩

- Vaidhyanathan, Googlization. ↩

- Sergey Brin, and Lawrence Page, “The Anatomy of a Large-Scale Hypertextual Web Search Engine,” Computer Networks and ISDN Systems 30(1-7) (1998), 107-117. ↩

- Amanda Spink, Dietmar Wolfram, B. J. Jansen, and Tefko Saracevic, “Searching the Web: ThePublic and Their Queries,” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 52(3) (2001), 226-234; Bernard J. Jansen and Udo Pooch, “A Review of Web Searching Studies and a Framework for Future Research,” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 52(3) (2001), 235-246; Dietmar Wolfram, “Search Characteristics in Different Types of Web-Based IR Environments: Are They the Same?” Information Processing and Management, 44(3) (2008), 1279-1292. ↩

- Karen Markey, “Twenty-Five Years of End-User Searching, Part 1: Research findings,” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 58(8) (2007), 1071-1081. ↩

- Nissenbaum and Introna, “Shaping the Web.” ↩

- The debates over Google as a monopoly were part of a Congressional Antitrust Subcommittee hearing on Sept. 21, 2011 and the discussion centered around whether Google is causing harm to consumers through its alleged monopolistic practices. Google has responded to these assertions. See P. Kohl and M. Lee, “Letter to Honorable Jonathan D. Leibowitz, Chairman, Federal Trade Commission,” December 19, 2011. ↩

- Kimberle W. Crenshaw, “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color,” Stanford Law Review 43(6) (1991), 1241–1299. ↩

- Patricia Hills Collins, Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment (New York, NY: Routledge, 1991); bell hooks, Black Looks: Race and Representation (Boston, MA: South End Press, 1992). ↩

- Diaz, “Through the Google Goggles”; Segev, Google and the Digital Divide; Nissenbaum and Introna, “Shaping the Web.” ↩

- Diaz, “Through the Google Goggles”; Segev, Google and the Digital Divide; Nissenbaum and Introna, “Shaping the Web”; Vaidhyanathan, Googlization of Everything. ↩

- See Kristen Purcell, Joanna Brenner, and Lee Rainie, Search Engine Use 2012, retrieved on 23 March 2012. ↩

- Segev, Google and the Digital Divide. ↩

- Cameron McCarthy, “Multicultural Discourses and Curriculum Reform: A Critical Perspective,” Educational Theory 44(1) (1994), 81-98. ↩

- Christian Fuchs, “Labor in Informational Capitalism and on the Internet,” The Information Society 26 (2010), 179-196. ↩

- For the concept of “symbol system” as domination, see Gerda Lerner, The Creation of Patriarchy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986). ↩

- See Jacqueline Bobo, Black Women as Cultural Readers (New York: Columbia University Press (1995); Maria St. John, M. “It Ain’t Fittin’,” Studies In Gender & Sexuality 2(2) (2001), 129; Janell Hobson, “Digital Whiteness, Primitive Blackness,” Feminist Media Studies 8 (2008), 111-126; Jennifer C. Nash, “Strange Bedfellows: Black Feminism and Antipornography Feminism,” Social Text 26(4 97) (2008), 51-76. ↩

- Nash, “Strange Bedfellows.” ↩

- Nash, “Strange Bedfellows.” ↩

- See Mireille Miller-Young, “Hip-Hop Honeys and Da Hustlaz: Black Sexualities in the New Hip-Hop Pornography,” Meridians: Feminism, Race, Transnationalism 8(1) (2007), 261-292. ↩

- See also Bobo, Black Women; Miriam Thaggert, “Divided Images: Black Female Spectatorship and John Stahl’s Imitation of Life,” African American Review 32(3) (1998), 481; St. John, “It Ain’t Fittin’.” ↩

- See Susanna Paasonen, “Trouble with the Commercial: Internets Theorised and Used,” in The International Handbook of Internet Research, eds. Jeremy Hunsinger, Lisbeth Klastrup, and Matthew Allen (Dordrecht: Springer, 2010), 411-422. ↩

- Paasonen, “Trouble with the Commercial.” ↩

- Gail Dines, Pornland: How Porn Has Hijacked Our Sexuality (Boston: Beacon Press, 2010). ↩

- Dines, Pornland, 48. ↩

- Dines, Pornland, 47. ↩

- Miller-Young, “Hip-Hop Honeys.” ↩

- hooks, Black Looks. ↩

- Miller-Young, “Hip-Hop Honeys.” ↩

- Purcell, Brenner, and Rainie, Search Engine Use 2012. ↩

- hooks, Black Looks. ↩

- Miller-Young, “Hip-Hop Honeys,” 262. ↩

- Jessica L. Davis and Oscar H. Gandy, “Racial Identity and Media Orientation: Exploring the Nature of Constraint,” Journal of Black Studies 29(3) (1999), 367-397. ↩

- Wendy Chun, Control and Freedom: Power and Paranoia in the Age of Fiber Optics (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2006); Jean Kilbourne, Can’t Buy My Love: How Advertising Changes the Way We Think and Feel (NY: Simon and Schuster, 2000); Anthony J. Cortese, Provocateur: Images of Women and Minorities in Advertising (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 2008); William M. O’Barr, Culture and the Ad: Exploring Otherness in the World of Advertising (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1994). ↩

- See Lisa Nakamura, Cybertypes: Race, Ethnicity, and Identity on the Internet (New York: Routledge, 2002); Nakamura, Digitizing Race: Visual Cultures of the Internet, (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2008); Lisa Nakamura and Peter Chow-White, eds., Race after the Internet (New York: Routledge, 2011); Anna Everett, Digital Diaspora: A Race for Cyberspace (Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 2009); André Brock, “Beyond the Pale: The Blackbird Web Browser’s Critical Reception,” New Media and Society 13(7) (2011), 1085-1103; André Brock, Lynette Kvasny, and Kayla Hales, “Cultural Appropriations of Technical Capital,” Information, Communication and Society 13(7) (2010), 1040-1059; Latanya Sweeney, “Discrimination in online ad delivery,” Queue Magazine 11(3) (2013), preprint available here; Safiya Umoja Noble, “Missed Connections: What Search Engines Say About Women,” Bitch 12(54) (2012), 37-41. ↩

- Chun, Control and Freedom. ↩

- Dan Schiller, How to Think about Information (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2007); Vincent Mosco, The Political Economy of Information (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1988). ↩

- Yochai Benkler, The Wealth of Networks: How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2006. ↩

- Sarah T. Roberts, Behind the Screen: Unveiling the Digital Labor of Online Content Moderation (forthcoming 2013). ↩

- Roberts, Behind the Screen, 16. ↩

- Google’s infographic can be found here ↩

- See Google’s Disclaimer here ↩

- Hindman, The Myth of Digital Democracy. ↩

- Hindman, The Myth of Digital Democracy. ↩

- Martin Feuz, Matthew Fuller, and Felix Stalder, “Personal Web Searching in the Age of Semantic Capitalism: Diagnosing the Mechanisms of Personalization,” First Monday, 16(2-7) (2011). ↩

- See Michael A. Peters and Ergin Bulut, eds., Cognitive Capitalism, Education and Digital Labor (New York: Peter Lang, 2011); Ergin Bulut, “Labor and Totality in ‘Participatory’ Digital Capitalism,” in New Times: Making Sense of Critical/Cultural Theory in a Digital Age, eds. Cameron McCarthy, Heather Greenhalgh-Spencer, and Robert Mejia (New York: Peter Lang, 2011), 51–70. ↩

- See Fuchs, “Labor in Informational”; Jonathan Burston, Nick Dyer-Witheford, and Alison Hearn, “Digital labor: Workers, authors, citizens,” Ephemera 10(3/4) (2010), 214-221. ↩

- Google Web History is designed to track signed-in users’ searches in order to better track their interests. Considerable controversy followed Google’s announcement and many online articles were published with step-by-step instructions on how to protect privacy by ensuring that Google Web History was disabled. See the Washington Post for more information on the controversy (last accessed on June 12, 2012). Google has posted official information about its project here (last accessed on June 22, 2012). ↩

- Feuz, Fuller, and Stalder, “Personal Web Searching.” ↩

- Thomas Nakayama and Robert Krizek, “Whiteness: A Strategic Rhetoric,” Quarterly Journal of Speech 81(3) (1995): 291-309. ↩

- Brock, “Beyond the Pale,” 1088. ↩

- See Fredrik Barth, Models of Social Organization (London: Royal Anthropological Institute, 1966); Richard Jenkins, “Rethinking Ethnicity: Identity, Categorization and Power,” Ethnic and Racial Studies 17(2) (1994), 197-223. ↩

- Mary Herring, Thomas B. Jankowski, and Ronald E. Brown, “Pro-Black Doesn’t Mean Anti-White: The Structure of African-American Group Identity,” Journal of Politics 61(2) (1999), 363. ↩

- Vaidhyanathan, Googlization; Oscar H. Gandy, “Consumer Protection in Cyberspace,” Triple C: Cognition, Communication, Co-operation 9(2) (2011), 175-189, retrieved October 1, 2010. ↩

- Jenkins, “Rethinking Ethnicity.” ↩

- Cheryl Harris, “Whiteness As Property,” in Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings that Formed the Movement, eds. Kimberlé Crenshaw, et al (New York, NY: The New Press, 1995). ↩

- Jenkins, “Rethinking Ethnicity.” ↩

- Davis and Gandy, “Racial Identity,” 367. ↩

- Jenkins, “Rethinking Ethnicity.” ↩

- Norman Fairclough, Critical Discourse Analysis (London: Longman, 1995). ↩

- Norman Fairclough, Analysing Discourse: Textual Analysis for Social Research (London: Routledge, 2003). ↩

- Fairclough, Analysing Discourse: Textual Analysis, 9. ↩

- Norman Fairclough, Analysing Discourse (Taylor and Francis, 2007). ↩

- Mikhail M. Bakhtin, The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays (Austin, TX: University of Texas, 2006, 1981), 281. ↩

- Carolyn M. West, “Mammy, Sapphire, and Jezebel: Historical Images of Black Women and Their Implications for Psychotherapy,” Psychotherapy 32(3) (1995), 458-466. ↩

- hooks, Black Looks. ↩

- Deborah Gray White, Ar’n’t I a Woman? Female Slaves In The Plantation South (New York: Norton, 1999). ↩

- Fairclough, Analysing Discourse. ↩

- Michel Foucault, The Archaeology of Knowledge, trans. R. Swyer (London: Tavistock Publishing, 1972), 229. ↩

- Foucault, Archaeology of Knowledge, 229. ↩

- Barney Warf and John Grimes, “Counterhegemonic Discourses and the Internet,” Geographical Review 87(2) (1997), 260. ↩

- Brock, “Beyond the Pale,” 1088. ↩

- To protect the identity of subjects in the websites and advertisements, I intentionally erased faces and body parts using Adobe Photoshop while still leaving enough visual elements for a reader to make sense of the content and discourse of the text and images. ↩

- Internet lore attributes the creation of the term “Googlebombing” to Adam Mathes who associated the term “talentless hack” with a friend’s website in 2001. A website dedicated to the history of web memes attributes the pre-cursor to the term to Archimedes Plutonium, a Usenet celebrity, for creating the term “searchenginebombing” in 1997. See here for more information (last accessed on June 20, 2012). Others still argue that the first Google-bomb was created by Black Sheep who associated the terms “French Military Victory” to a redirect to a mock-page that looked like Google and listed all of the French military defeats, with the exception of the French Revolution where the French were allegedly successful in killing their own French citizens. The first, most infamous instance of this was the case of Hugedisk magazine linking the text “dumb motherfucker” to a site that supported George W. Bush. See: Michael Calore; Scott Gilbertson (January 26, 2001), “Remembering the First Google Bomb,” Wired News, archived from the original on February 25, 2007, retrieved January 27, 2007 for more information. ↩

- Brin and Page note that in the Google prototype, a search on “cellular phone” results in PageRank™ making the first result a study about the risks of talking on a cell phone while driving. ↩

- Judith Bar-Ilan, “Google Bombing from a Time Perspective,” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 12(3) (2007), article 8. ↩

- In 2003, radio host and columnist Dan Savage encouraged his listeners to go to a website he created: http://santorum.com/ and post definitions of the word “santorum” after the Republican Senator made a series of anti-gay remarks that outraged the public. ↩

- Vaidhyanathan, Googlization. ↩

- See Google’s Disclaimer here. ↩

- Diaz, “Through the Google Goggles.” ↩

- Nissenbaum and Introna, “Shaping the Web,” 9. ↩

- See Harris, “Whiteness As Property”; hooks, Black Looks; Collins, Black Feminist; George Lipsitz, The Possessive Investment in Whiteness: How White People Profit from Identity Politics (PA: Temple University Press, 1998); Robert Jensen, The Heart of Whiteness: Confronting Race, Racism, and White Privilege (San Francisco, CA: City Lights, 2005); Richard Dyer, White (London: Routledge, 1997). ↩

- See Joseph C. Dorsey, ‘“It Hurt Very Much at the Time’: Patriarchy, Rape Culture, and the Slave Body-Semiotic,” in The Culture of Gender and Sexuality in the Caribbean, ed. Linden Lewis (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2003), 294-322. ↩

- hooks, Black Looks; Susanne Kappeler, The Pornography of Representation (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1986). ↩

- See Michael K. Brown, et. al., Whitewashing Race: the Myth of a Color-Blind Society (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003). ↩

- Lipsitz, The Possessive Investment; see also Brown, Whitewashing Race; and Jensen, The Heart of Whiteness. ↩

- See Helen A. Neville, M. Nikki Coleman, Jameca Woody Falconer, and Deadre Holmes, “Color-Blind Racial Ideology and Psychological False Consciousness Among African Americans,” Journal of Black Psychology, 31(1) (2012), 27-45. ↩

- See Christine Pawley, “Unequal Legacies: Race and Multiculturalism in the LIS Curriculum,” Library Quarterly, 76(2) (2006), 149-169. ↩

- Brown, Whitewashing Race; Jensen, The Heart of Whiteness; Chris McGreal, “A $95,000 Question: Why are Whites Five Times Richer than Blacks in the US?” Guardian, UK, retrieved September 15, 2010. ↩

- Brown, Whitewashing Race; and Crenshaw, “Mapping the Margins.” ↩

- Lipsitz, The Possessive Investment; Brown, Whitewashing Race; Pamela Burdman, “Race-blind Admissions,” retrieved September 14, 2010. ↩

- See for instance, Brendesha M. Tynes and Suzanne L. Markoe, “The Role of Color-Blind Racial Attitudes in Reactions to Racial Discrimination on Social Network Sites,” Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 3(1) (2010), 1-13. ↩

- Brown, Whitewashing Race. ↩

- Don Heider and Dustin Harp, “New Hope or Old Power: Democracy, Pornography and the Internet,” Howard Journal of Communications 13(4) (2002), 285-299. ↩

- David J. Gunkel and Ann Hertzel Gunkel, “Virtual Geographies: The New Worlds of Cyberspace,” Critical Studies in Mass Communication 14 (1997), 123-137; John Vernon Pavlik, New Media Technology: Cultural and Commercial Perspectives (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1996); Douglas Kellner, “Intellectuals and New Technologies,” Media, Culture and Society 17 (1995), 427-448; John Perry Barlow, “A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace,” retrieved May 10, 2011. ↩

- Annette Kuhn, The Power of the Image: Essays on Representation and Sexuality (NY Routledge, 1985). ↩

- Heider and Harp, “New Hope.” ↩

- Heider and Harp, “New Hope.” ↩

- Alice Mayall and Diana E. Russell, “Racism in Pornography,” Feminism and Psychology 3(2) (1993), 295. ↩

- T. A. Gardner, “Racism in Pornography and the Women’s Movement,” in Take Back The Night: Women on Pornography, ed. Laura Lederer (NY: William Morrow, 1980), 105-106. ↩

- See Susanna Paasonen, “Revisiting Cyberfeminism,” Communications: The European Journal of Communication Research 36(3) (2011), 335-352; Stacy Gillis, “Neither Cyborg Nor Goddess: The (Im)possibilities of Cyberfeminism,” in Third Wave Feminism: A Critical Exploration, eds. Stacy Gillis, Gillian Howie and Rebecca Munford (London: Palgrave, 2004), 185-196; Cornelia Sollfrank, “The Final Truth about Cyberfeminism,” in Very Cyberfeminist International, eds. Helene von Oldenburg and Claudia Reiche (Hamburg: OBN, 2002), 108-113; Donna J. Haraway, Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature (London: Free Association Books, 1991). ↩

- Judy Wajcman, Feminism Confronts Technology (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1991); Wajcman, “Feminist Theories of Technology,” Cambridge Journal of Economics 34 (2010), 143–152. ↩

- Wajcman, Feminism Confronts, 5. ↩

- See Bruce Sinclair, “Integrating the Histories of Race and Technology,” in Technology and the African American Experience: Needs and Opportunities for Study, ed. Bruce Sinclair (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004), 1-17; Everett, Digital Diaspora; Rayvon Fouché, “Say It Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud: African Americans, American Artifactual Culture, and Black Vernacular Technological Creativity,” American Quarterly 58(3) (2006), 639-661; Alondra Nelson, Thuy Linh N. Tu, and Alicia Hedlam Hines, Technicolor: Race, Technology, and Everyday Life (NY: New York University Press, 2001); Nakamura, Digitizing Race; Alexander G. Weheliye, “‘I Am I Be’: The Subject of Sonic Afro-Modernity,” Boundary 2 30(2) (2003), 97-114; Ron Eglash, “Race, Sex, and Nerds: From Black Geeks to Asian American Hipsters,” Social Text 20(2) (2002), 49-64. ↩

- Wajcman, “Feminist Theories,” 150. ↩

- Everett, Digital Diaspora, 149. ↩

- See Everett, Digital Diaspora. ↩

- See Hazel Dicken-Garcia, “The Internet and Continuing Historical Discourse,” Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly 75 (1998), 19-27. ↩

- See Nancy K. Baym, “The Emergence of Community in Computer Mediated Communication,” in Cybersociety: Computer-Mediated Communication and Community, ed. Steven G. Jones (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1995), 138-163. ↩

- See Tom Postmes, Russell Spears, and Martin Lea, “Breaching or Building Social Boundaries? SIDE-Effects of Computer-Mediated Communication,” Communication Research 25 (1998), 689-715. ↩

- Gunkel and Gunkel, “Virtual Geographies,” 131. ↩

- Langdon Winner, The Whale and the Reactor: A Search for Limits in an Age of High Technology (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1986); Arnold Pacey, The Culture of Technology (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1983). ↩

- David J. Leonard, “Young, Black (or Brown), and Don’t Give A Fuck: Virtual Gangstas in the Era of State Violence,” Cultural Studies Critical Methodologies 9(2) (2009), 248-272. ↩

- Nakamura, Cybertypes. ↩

- Lori Kendall, Hanging Out in the Virtual Pub: Masculinities and Relationships Online (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2002). ↩

- Chun, Control and Freedom; André Brock, “Life on the Wire,” Information, Communication and Society, 12(3) (2009), 344-363. ↩

- David Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005); Fairclough, Analysing Discourse. ↩