Do away with the actor and you do away with the means by which a debased stage-realism is produced and flourishes. No longer would there be a living figure to confuse us into connecting actuality and art; no longer a living figure in which the weakness and tremors of the flesh were perceptible.

– Edward Gordon Craig, from “The Actor and the Über- Marionette”

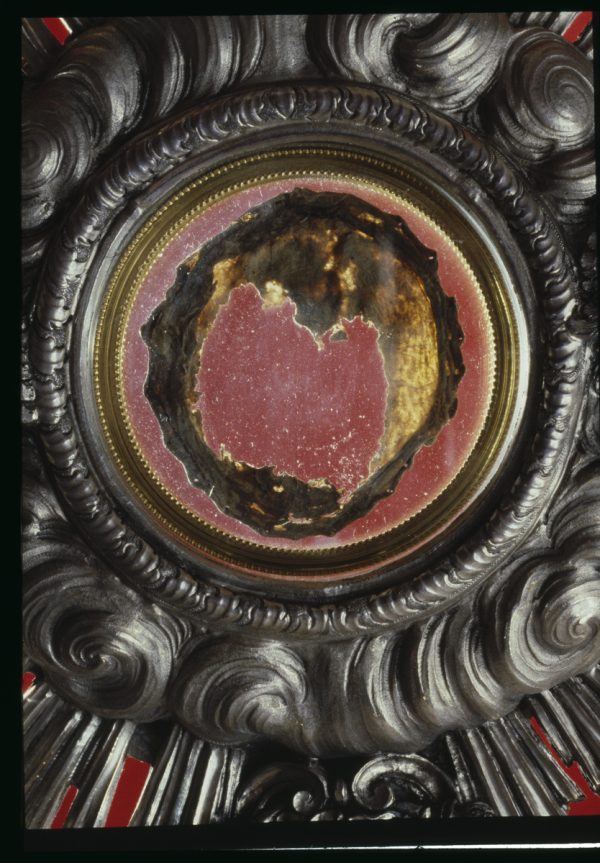

When I was ten, I found a religious pamphlet in my stepmother’s purse, which I obsessively read and re-read. It featured a story about an eighth-century Basilian monk who, saying mass, was overcome with doubt about the transformation of the communion elements of bread and wine into the flesh and blood of Jesus Christ. As this monk began to doubt, the bread and wine turned to real flesh and real blood before his eyes. The pamphlet spent the rest of its brief pages describing the scientific testing that had been done to prove that the fleshy membrane and coagulated blood, conserved in an ornate monstrance, were, in fact, living tissues from a human body and untreated by preservatives. Both their manifestation and continual survival were miraculous. The church had confirmed the miracle and, most recently, in 1971, so had Dr. Edward Linoli, director of the hospital in Arezzo and professor of anatomy, histology, chemistry, and clinical microscopy.1

For a budding religious child, a story of this kind – about a holy man suspecting that the major tenet of the Catholic faith, the transubstantiation, was untrue –created good measures of suspense. The layperson scientific report excited me too. But most compelling, the thing from which I couldn’t look away, was the image of an opulent metal standard enclosing a textured slice of bodily tissue (which comes from the heart, experts have determined)2 and five lumps of congealed blood. Pieces from the human body’s interior. Jesus’ flesh and blood. Right there. It was a miracle. It was monstrous.

In nearly all of the literature distributed by the church about the miracle of Lanciano, the reader sees photographs of human tissue and clotted blood, and reads the story close to how I have written it. Building on the photographic proof of the event, the authors describe the mysteriously occurring flesh and blood first as miracle, in the narrative account of the poor monk, and then remarkably, as evidence. Evidence of the transubstantiation: Christ’s body is truly manifest in the host and sacramental wine, whether it appears this way or not. This impossible miracle proves it. The Catechism asserts that, “Under the consecrated species of bread and wine, Christ himself, living and glorious, is present in a true, real, and substantial manner” and that, “ by the consecration of the bread and wine there takes place a change of the whole substance of the bread into the substance of the body of Christ our Lord and of the whole substance of the wine into the substance of his blood.”3 The Lanciano miracle literature goes one step further than assertion and offers empirical study that supports the fact of transubstantiation, no longer merely an article of faith:

1. The “miraculous Flesh” is authentic flesh consisting of muscular striated tissue of the myocardium.

2. The “miraculous Blood” is truly blood. The chromatographic analysis indicated this with absolute and indisputable certainty.

3. The immunological study shows with certitude that the flesh and the blood are human, and the immuno – hematological test allows us to affirm with complete objectivity and certitude that both belong to the same blood type AB – the same blood type as that of the man of the Shroud and the type most characteristic of Middle Eastern populations.

4. The proteins contained in the blood have the normal distribution, in the identical percentage as that of the serous-proteic chart for normal fresh blood.

5. No histological dissection has revealed any trace of salt infiltrations or preservative substances used in antiquity for the purpose of embalming.4

In the literature, these tissues are made to operate as both miracles and material facts. The pamphlet boasts that scientists, especially Dr. Linoli, have performed hundreds of tests, have walled up the miracle on all sides with empiricism, and have found that these objects require little of our faith. They are empirical material objects, testaments to the transformation of food and drink to flesh and blood at the altar on Sunday mornings, and testaments to positivist value. Miracles are especially worthwhile if they are objectively certain.

Ordinarily, in the mass, communion is neither so gory nor so indisputable. When I was little, reading about the Italian transubstantiation made me grateful that a miracle of material transformation did not happen weekly in my mouth. Kept in the eighth-century in a little Italian church I would never attend, the miracle of Lanciano produced just the right amount of fleshy reality. Why? Because it was already threatening to turn my clean white host sprinkled cursorily with sacramental wine into the palpable warmth of viscera. It presented too much body.

The excessive materiality of the Lanciano event draws attention to the distinct lack of corporeality in the regular Eucharistic sacrament. In fact, on a regular Sunday, the crisp, white host does an extraordinary work as stand-in. It is made to bear the traits of both an omnipotent, invisible God and a body scripturally rendered as emphatically fleshy – brutalized by physical torture and crucifixion, Christ’s body is blood, skin, meat and bone. A lot of work for little unleavened bread.

Lanciano also reminds us that the utterance, “This is my body,” declared by the priest in preparation for communion, where the transformative event takes place, is loaded indeed. Host and script, in the liturgy, are powerful, if unlikely collaborators. The extraordinary ritual transformation in communion is invisible and also emphasized for congregation in a distinct dramaturgical compendium of words, gestures, and visible and invisible props and characters. In this article, I trace the dramaturgy of the Eucharistic liturgy as it plays with bare-bones presentation and dynamic invisibility to produce a unique experience of faith that requires none of the empirical assertions of the Lanciano pamphlet.

In an announcement that amounts to a proclamation against all evidence, the priest, in the Catholic Mass, holding the ‘bread,’ often a circular, cracker-thin wafer declares: “This is my body.” The declaration that this here is identifiable as the body of Christ is particularly strange, since no body actually appears. The liturgical celebration of the Eucharist can be read against the certain proof of the Lanciano miracle in that, while the Catholic event features a demonstrative assertion, the demonstration itself, especially read theatrically, presents itself as a lack. The Eucharistic theatre features a play of absences and contrary “evidence,” profound distancing effects, which function as incitements to faith. In the Eucharistic rite, the leading actor fails to appear, the dramatic miracle fails to take place, and the dramaturgical framing exacerbates artifice rather than conceal it. Read dramaturgically, the Eucharistic celebration pairs demonstration and invisibility in ways that embellish the aporetic, producing a theatre that demands total faith.

It is easy to imagine ways in which the mass is itself theatrical. There is, after all, a liturgical script the priest and congregation follow, located in printed form, in the Sunday Missal. The catechism and surrounding theological and scholarly works confirm and reiterate this script. The church space is itself set up for a small group of actors to be watched by an audience/congregation. The priest/actor plays to the audience, facing them and speaking scripted lines audibly. He is in ritual costume. So are his altar boys and girls. He works with the same props from week to week, and plays the same character(s) unfailingly.

Joy Palacios, scholar of the theatrical nature of the mass, and early modern French clergy’s anxious efforts to distance themselves from the actors of theatres, writes about a historical transition from the mass divided from its attendants by an obscuring screen in the Middle Ages, to its emergence from behind the screen in the mid seventeenth-century with new attention to visual representation:

During the Middle Ages the ceremonies of the mass had not lent themselves to theater comparisons because they had unfolded in an enclosed area called a chancel accessible only to priests and separated from the laity by a wall or screen called a jubé, hence the notion that worshippers would hear rather than see a mass. Preaching, by contrast, took place in the part of the church where the laity gathered, called the nave. Preaching could even take place outside the church in the open air during missions. Thus, lay people in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries heard the mass but saw preachers. In the seventeenth century, however, French churches gradually opened their chancels and placed ceremonies on display.5

Moving communion from invisibility to visibility, which Palacios follows in exciting detail, lead to a construction of the optics of ceremonial sacrament within the Catholic mass, and to thoughtful clergy training on choreography of their priestly bodies. Suddenly, Palacios argues, priests were comparable to actors. They were “preaching for the eyes.”6

Alongside the blocking of bodies in and around the alter space, I am interested in the choreographic framing of attention to and understanding of the spiritual body of Christ presenced in the Eucharist bread within the dramaturgical structure of the mass. Catholic mass, while it can be viewed from the perspectives of performance analysis, is much more than theatre. The transubstantiation tenet, established in the thirteenth-century, that the bread of the Eucharistic celebration really becomes the body of Christ, certainly undermines analysis of what one is seeing and can see. At the same time, studying the mass, which has been designed with spiritual and highlighted visual elements in mind, from a theatrical perspective, uncovers a knotted tangle of dramaturgy’s encounter with mystery.

In what follows, I focus, not on the entirety of the mass, or even the full preparation of the gifts through the congregational departure following their sacramental consumption. Rather, I have chosen to focus on the particular site of the citation of Christ’s words at the Last Supper through the transubstantiation and eating of the flesh. Even in this limited site of analysis, I locate several major dramaturgical elements worth investigation. These include script, props, scene, actor, and acting style – and all, read carefully, subvert the conventional designations these terms entail. At the limited site of the “This is my body” script delivery and the sacramental ingestion, I also note three actors in need of interrogation: the priest, the congregation, and God Invisible, the “Absentee par excellence” who nonetheless is so present that the other actors are able to eat his manifested body.

Jean-Luc Nancy comments upon the strangeness of the utterance “This is my body” in his work on the body entitled, Corpus. He, in fact, begins his text with the words: Hoc est enim corpus meneum.7 Nancy is astonished by the notion that: “…this this, here, is the thing we can’t see or touch, either here or anywhere else – and that this is that (God, or the absolute, if you prefer) – and the fact that “that” has a body, or that “that” is a body…”8 The idea that this bread is that body of God, that the this of the bread is “[t]he presentified “this” of the Absentee par excellence…”9 is astonishing, nearly beyond belief. While this article argues that the Eucharistic celebration in the Mass is theatrical, and uses the tropes of theatre as implements of investigation, eating the corpus may be the moment where the Eucharist ontologically breaks from theatre – for whereas in theatre, one is asked to temporarily suspend one’s disbelief in order to partake in the illusion, the Catholic Mass requires that believers actually believe, despite all evidence to the contrary, that this bread is actually that body and that God, who is the Absentee par excellence, is both present as an invisible spirit and present as a sacrificed body in the bread. God as invisible actor and invisible body has to be believed rather than seen and believed in the most extreme way – beyond the temporal boundaries of the mass, and beyond the usual visual expectations of quotidian life via the actual ingestion of a substance sensuously (and perhaps cognitively) experienced as bread and simultaneously believed to be body. “This is my body” is a profoundly disruptive utterance in terms of conventional opsis. And so is the eating of the bread that is believed to be a body. The Eucharistic sacrament, given the tension between what is concealed and what is given in the rite, presents radically high demands for its audience – it demands that they depend upon the suspended. Communion is a ritual practice in radical contingency.

It is important to remember that while we recognize that the Eucharistic rite refers to the original event of the (first) Last Supper as enacted by Jesus before his death, for his disciples, our understanding of the original event on which the sacrament of communion is built is knowable to us only via the biblical text.10 We have no other historical documents depicting the sacred meal, in which Christ served food and drink to his followers and asked them to share meals to commemorate him. Very little is known about Eucharistic church practice before the Fourth Century. The historical documents are sparse, and the validity of those that do exist is contested. The aspects we do know amount to an assortment of generalities surrounding the practice of eating the Eucharistic bread together with other believers in a common location, and on one’s own or with others at home. It seems, for instance, that the Eucharist, at least in North Africa, often took the form of believers supping together. 11 There are early sects who shared a commemorative meal each time they met.12 Tertullian (who, incidentally, was suspicious of theatre) describes the spiritual benefits of the faithful taking bread home from gatherings to eat later if they were fasting at the time of meeting. 13 According to Paul Bradshaw, a leading scholar of Eucharistic history, aside from these sparse accounts, little else in known about the communal practice of eating the Lord’s Supper in the first centuries following the death of Christ. It does seem, though, that the Eucharistic rite of the post Vatican II sacrament in my hometown of Deep River, Ontario, is not so far from the bread-breaking practices of early Christians, who took Jesus’ commandment to remember him by eating and drinking seriously. The contemporary mass is even less distant from the Fourth Century ritualistic practices of the church as it began to formalize its rituals in ways recognizable to contemporary mass attendants.

What is exciting for a contemporary study of the sacrament of communion is that, beginning in the Fourth Century, the mass began to take a shape akin to the mass that is observed today.14 Once Christians were no longer being systematically persecuted, they began to institutionalize and thus formalize their religion in ways that resemble the contemporary liturgy. Bradshaw describes the evolution of Fourth Century meetings like this:

Christians were no longer subject to persecution, but were now followers of a legitimate and respectable religion, a cultus publicus that sought the divine favour in order to secure the well-being of the state. So it needed to have more of the appearance of other contemporary religions – temples, altars, a visible priesthood, and so on – and its worship therefore took on more features of the worship of other religions. Its numbers grew, and so it occupied larger and grander buildings than before, and consequently in worship became grander in style…15

Fourth Century examples of prayer from the Didache are quite similar to prayers we recognize from the contemporary mass. For example, Prayer 1 from the Sarapion reads (in translation):

To you we offered this bread, the likeness of the body of the only-begotten. This bread is the likeness of the holy body, because the Lord Jesus Christ, in the night he was betrayed, took bread and broke (it) and gave (it) to his disciples, saying, ‘Take and eat. This is my body which is broken for you for forgiveness of sins…’16

And so on. There is much overlap in the Didache with the mass I participated in as a young girl. The evolution of the rite in accordance with cultural, religious and state practices suggests that the liturgical practice we have now was constructed decisively, over time, and that its style reflects formal and theological consideration about how the mass ought to be constructed.

The brief text of communion in my home parish, and many parishes like it, is as follows17:

(Priest is behind the altar; Congregation is kneeling at their seats, facing him)

Priest: On the night he was betrayed he took the bread, and giving you thanks he broke the bread and gave it to his disciples, saying:

TAKE THIS, ALL OF YOU, AND EAT OF IT: FOR THIS IS MY BODY, WHICH WILL BE GIVEN UP FOR YOU.

When supper was ended, he took the cup, and giving you thanks he took the cup, and gave it to his disciples, saying:

TAKE THIS, ALL OF YOU, AND DRINK FROM IT: FOR THIS IS THE CUP OF MY BLOOD, THE BLOOD OF THE NEW AND EVERLASTING COVENANT; WHICH WILL BE SHED FOR YOU AND FOR THE FORGIVENESS OF SINS. DO THIS IN MEMORY OF ME.

Blessed are you, Lord, God of all creation. Through your goodness we have this bread (wine) to offer, the fruit of the earth and the gift of human hands. It will become for us the bread of life (our spiritual drink)

(During this time, the priest sprinkles some wine on the bread and drinks the rest of the cup.)

All: Blessed be God forever.

(Omitting this part, which includes the Lord’s Prayer and an Offering of Peace amongst believers)

All: Lamb of God, you take away the sins of the world: have mercy on us. Lamb of God, you take away the sins of the world: have mercy on us. Lamb of God, you take away the sins of the world: grant us peace.

Priest: This is the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world. Happy are those who are called to his supper.

All: Lord, I am not worthy to receive you, but only say the word and I shall be healed.

Communion Minister: The body of Christ.

Communicant: (Take host and eat it, making sign of the cross) Amen.

It is both priest and congregation who utter this script in tandem.18 The priest, of course, is the one who cites the words of, and who can be said to play the role of Christ. His presentation of the role occurs narratively and imitatively, and is played with a distance that points to the theatricality of the event. The priest’s movement, his use of the ritual stage frames the Eucharist as a particular segment of the whole of the mass as he speaks from podia and from in front of the altar, but never from behind it until the moment where the communion elements are prepared. The contemporary priest’s “scene” or “set” is the entirety of the platform in front of the congregation – Catholicism has been expert in organizing the framing around the Eucharist scenographically. Adolph Adam whose Eucharistic Celebration is an attempt at a historic and theological account of the celebration of the Eucharist written in response to19 writes about preparing the altar, citing the General Instruction of the Roman Missal: “The altar should be freestanding to allow the ministers to walk around it easily and Mass to be celebrated facing the people. It should be so placed as to be a focal point on which the attention of the whole congregation centres naturally.”20 Further instructions ask that the priest approach the altar for the first time only when the preparation of the bread and wine has begun.21 This framing by blocking posits the Eucharist as distinct from the rest of the mass and anticipates further instruments of framing. One such device serves to indicate that the priest is “only acting” as Christ.

The priest, after all, plays both himself and Jesus. The dual nature of the actor presenting as himself and as the character he plays cannot but remind one of Bertolt Brecht’s recommendations for playing in order to create emotional distance and cognitive engagement.22 The estrangement effect Brecht is so famous for developing into an acting style meant to induce critical thinking and political transformation in audiences by disrupting their politically pacifying emotional responses already has roots in the ways Sunday priests play as though they are Christ with emphasis on the “as though” rather than the “are.” No priest in my hometown mass ever attempted to deliver a believable performance of his being the Son of God. In Brecht’s words, “He makes it clear that he knows he is being looked at.”23 The priest’s avoidance of naturalistic acting techniques is necessary for maintaining the congregation’s relationship to him as intermediary or ritual stand-in for Christ. Playing at Christ rather than playing Christ as a palpable character also allows the priest to perform his personal act of worship in saying the mass (he receives the gift of communion, consuming the elements too, remember). The Cathechism is clear on the matter of distance, saying, after Saint John Chrysostom, “It is not man that causes the things offered to become the Body and Blood of Christ, but he who was crucified for us, Christ himself. The priest, in the role of Christ, pronounces these words, but their power and grace are God’s.”24

One also might think here of Domenico Pietropaolo’s article Whipping Jesus Devoutly: The Dramaturgy of Catharsis and the Christian Idea of the Tragic in which soldiers in Passion plays are depicted as having to “perform the act of scourging Jesus, while speaking words of savage cruelty to him, but they must appear to do so as an act of piety rather than as an act of cruelty.”25 They are expected to “play and yet not to play the roles of the historical torturers.”26 The dual nature of the performance of the soldiers serves to complicate naturalistic or straightforwardly mimetic styles of playing.27

It is important that the priest play Jesus when re-enacting the Last Supper, but that he not play him too well. The Eucharistic rite is not simply a restaging, but is also an act of worship – thus, the priest takes an attitude of piety and adoration for Jesus, while simultaneously toggling speaking the words of Christ in first person and acting as historic narrator. In this way, the congregation never suspects that the priest has actually transformed into Christ – they know that he is acting. The priest’s intentional avoidance of attending to direct imitation in his delivery of Christ’s words points to artifice and the actor as stand-in, rather than the actualization of the real thing – as in the case of the transubstantiation. At the same time, the priest is really worshipping, in the present moment. In the brief lines uttered during communion, the priest becomes a living citation, standing in for the Lamb of God without too much indulgence in role-playing and playing the role of community priest, likely the role closest to what he would identify as his true self. This is never mistaken for that. To complicate the certitude of the “this,” the priest also acts in the present moment of the event, as an instrument of historical iteration, for the supper is a repetition of one the night before Christ’s death.

The layered temporality of the Eucharistic rite serves as another distancing effect. What of, for instance, the grammatical structure of the line: “On the night he was betrayed he took the bread, and giving you thanks he broke the bread and gave it to his disciples, saying, ‘Take this all of you and eat it’…?” The smattering of shifts in pronouns is alarming. On the night he – Jesus – was betrayed, he – Jesus – took the cup and gave you – surely the priest is invoking God as the great you here – thanks and praise. He – Jesus – broke the bread and gave it to his disciples – the subsequent you – saying, ‘Take this all of you and eat it…” In this moment, the priest speaks, as himself, to God and speaks the words of Christ to his disciples and also speaks as himself to the congregation of believers. These layers of pronouns invoke several temporalities at once – and cause the priest and the congregation to play several roles at once – they are themselves in the here and now remembering the original event of the Last Supper, and they are enacting the Last Supper as it happened centuries ago in full recognition of its having passed (they are already redeemed). They also repeat the original response to Christ’s command, participating in an iterative recurrence. These utterances are performative, terribly important to a Sunday morning. They are what make the transformation of elements happen; the present moment is made sacred precisely by this momentary dwelling in long historic and divine time.

The framing of the semi-imitative words of Christ within the narrative construction of the script that reads in the past tense should point to the priest’s citational and theatrical role. That these are not his words; that This is not his body, becomes apparent through the drawing of attention to the citational nature of the priest’s words.28Before the profoundly enigmatic utterance, “This is my body,” the priest frames the direct citation of Christ’s words, saying, “On the night he was betrayed, Jesus…” The invocation of the past tense indicates within the mass that this Eucharistic rite is an iteration of an original event. However, this is where the utterance, “This is my body,” begins to intervene into the well-established artifice of the priest’s role. For, as we know, Catholic theology is founded on the belief in transubstantiation. During the moments where the priest cites the words of Christ, the bread really does become his body.29 The performative utterance where something happens and is produced by what is said, as described by J.L. Austen, is anticipated by the tenets of the Catechism, which are direct about the performative and miraculous power of declarations: “This is my body, he [the priest] says. This word transforms the things offered.”30

Despite Catholic belief that words uttered under the right circumstances can transform substances, it seems obvious that, “This is my body” does not and cannot act as an appeal to proof, since so many of the theatrical constructions around the utterance affect a sense of distance from the immediacy of reality. The belief that the bread actually is the body of Christ seems to subvert this assumption about how affect is conventionally achieved via alienating elements. However, if the belief in the transubstantiation relies on faith– that is, on a leap not at all based on sight or a belief that necessarily relies on an aversion to evidence, then perhaps the arrival of God’s body can only occur despite all evidence to the contrary. In the midst of a theatre that draws attention to the priest as actor rather than the Son of God he portrays, God can still appear, and he does so, but in radical contradiction to the visible. In the realm of faith, this apparent contradiction – that the dramaturgical elements surrounding the priest’s role embellish artifice rather than attempt to depict God in any believable way but that the God depicted in this distancing way nonetheless arrives completely – is most apt.

But how does God arrive? In what way does he appear? For one, he becomes incarnated in the props of the Eucharist. This presencing of the body occurs outside the domain of visibility, except in so far as what is visible – i.e. the bread – is not what is really there. Likewise, God’s full presence is assumed, though he does not show himself in any way. What does it mean for the liturgical theatre of the Eucharist to take as its main actor an Invisible God, and to declare his presence in the most radical way via the utterance and its actualization: “This is my body?”

In the transformation of bread to Christ’s body, the artifice of theatricality is in some ways subverted by the presencing of the “real thing,” but, on the surface, the bread acts precisely as a prop. The priest lifts it as Christ would and then the congregation eats from the chalice, wherein bread stands in for body. The status of the prop is such that it acts in place of the actual thing from life. It is, as it were, the sign for the referent in the “real world.” What can one make of a liturgical prop that appears to follow the formal register of the stage property – bread standing in for the original bread and Christ’s body – acting analogously – but that is accounted for, in practice, as being the actual body of the actual Christ, who lived two thousand years ago, when he first gave his body in the form of a sacrificial meal and then at Golgotha? Transubstantiation inverts mimesis – not by giving a real object in place of a fake one, but by presenting the fake one and simultaneously maintaining that what appears is not actually what is. This unconventional presentation and conception of the prop does not come without its tensions. As Nancy says, “But we certainly feel some formidable anxiety: ‘here it is’ is in fact not so sure, we have to seek assurance for it. That the thing itself would be there isn’t certain.”31 Likewise, Nancy utters his hesitation and the inadequacy of the stand-in:

“But instantly, always, the body on display is foreign, a monster that can’t be swallowed. We never get past it, caught in a vast tangle of images stretching from Christ musing over his unleavened bread to Christ tearing open his throbbing, blood-soaked Sacred Heart. This, this … this is always too much, or too little, to be that.”32

What Nancy points to is the unlikely miracle of faith in the face of inadequate evidence, of inadequate signification. Representations of Christ’s body in religious and cultural history present as being too much or too little in relation to the body of God, in its immense symbolic and spiritual weight. The bread, under this aesthetic analysis, is too little to be the body of God. The liturgical property serves as a reminder of its inadequacy as stand-in, and generates in its audience (and masticator) a natural disbelief or suspicion. It is in its failure to appear seamlessly that the Eucharistic bread is the perfect prop for an audience from whom the most audacious faith is required, however. It is precisely in the subversion of dramaturgical categories that the Eucharist asserts itself as a theatre of faith.

The ingestion of Christ’s body, via bread resembling bread, plays with appearance and faith in preposterous dimensions. Taking communion is a contradictory sensory experience. Visibly, the bread resembles bread. In the mouth, it sensuously cues the taste and texture of bread or wafer. In fact, Adam notes that great efforts ought to be made to have the bread in Mass resemble food.33 The ritual property has been considered at length and its appearance decisively errs on the side of food and not corpus. In the Eucharist, the congregation is asked to sensuously interpret bread, and is asked to simultaneously imaginatively interpret beyond bread to the eating of wounded flesh. She is, in a way nearly Stanislavskian, asked to act. To rehearse imagined circumstances until they palpably layer against the artifice of the ritual stage. “We always assent to sense: beyond sense, we lose our footing,” Nancy tells us.34 This “beyond sense” is exactly the territory of faith. The congregation member is supposed to experience the deepest proximity to God in ingesting the host. She is meant to enter into communion with God through the act of worshipful eating, and her ideal condition is not that of healthy skepticism or Brechtian cognitive distance. The Eucharistic transubstantiation could not cause the congregation to lose its footing more – but of course, this lost-footing is exactly the point. Where sense departs, faith arrives. It is then we take a leap.

The Eucharist, while theatrical and steeped in visuality, does not show everything. The liturgy’s major prop does not indicate as a prop usually does – it points to the historic bread of the last supper, but does not resemble the thing it ultimately ought to represent.

Furthermore, the notion of “prop” in the context of communion is itself subversive. The Eucharist’s major prop is also its main character. Catholics are themselves cognisant of this play of concealment and revelation alongside the interchangeablity of prop and character. As Adam writes:

Beneath the veil of the sacramental signs, it becomes real presence. As often as the congregation follows the command Jesus gave at his Last Supper, ‘Do this in memory of me,’ the risen Christ becomes present, together with his self-giving love, his obedience to suffering, his will to save, and his intercession for all people. Hidden under the visible signs of bread and wine, he is present as the high priest of the new covenant with his body given for us, his blood shed for us.35

Adam’s attention to veils, misleading visible signs and the appearance of God through the false indicator of bread leads us to our final dramaturgical consideration: that of the Invisible lead actor.

Ironically, the absence of God and his failure to appear requires the least proof in this dramaturgical reading. It is easy to take for granted that God has simply never visibly shown himself during the liturgy. God is the Absentee par excellence, but he is also omnipresent and the one through and for whom the mass is conducted. He is, in this way, both the invisible lead and the invisible witness – the “congregation” watching the congregation. He is also the Great “You” of the script that reads, “On the night he was betrayed he took the bread, and giving you thanks he broke the bread and gave it to his disciples, saying…” Rule XXXVI of the Regulae theologicae of Alain de Lille tells us that: “Whenever a demonstrative pronoun refers to God, it falls away from demonstration.”36 The Eucharist invokes a God who is indemonstrable. This play of obscurity may affect a feeling of the sublime in the congregation.37, 54 [First published in 1757]).] But, of course, Christ is also eaten by his audience, who believes him to be present according to the bold assertion, “This is my body.” And here is another tension between the audacity of the claim about presence and what is actually seen and experienced by the community of believers: on the one hand, we have a body, brought forth from the past into the present by divine rite – the body of a god appearing here and now, and each Mass until he returns so “palpable” it can be eaten. Beneath the veil of bread, which is real, an invisible God rests. And on top of all this, the believers are assured of God’s presence as Spirit – also wholly unwitnessable. One could conceivably ask a believer, “Have you ever seen God?” to which they could surely reply, “No. But I eat his sacrificed body every Sunday.” A Catholic audience member is caught between a visually rich liturgical theatre and an incalculable, wholly unapproachable God. Between a wholly other Absentee and the repeated eating of that aporetic Spirit, who meal after meal “appears,” omnipresent and “certainly” present at the Mass, though never visible.

The inaccessibility of God combined with the assertion of his total presence points to a contradiction that is exacerbated by the messianic/eschatological promise that He is coming back. If not here yet, then where and when is He? As the congregation waits, they enter a relationship of deferral with Christ, situating Him as about to arrive one day in the future. He will come again. Christ is simultaneously cited by the priest who locates Him in the past, in the time of the early church, the time described in the gospels. Nonetheless, Christ is radically present, characterized by the priest in the moment of the mass as being the one who offers the gifts of His body and blood to the congregation. The communion elements, for Catholics, don’t just represent Christ’s sacrificial flesh and blood but are ingested as miraculously presenced. A brief journey through the articles of the Catechism describes the layered time of the Eucharist sacrament: the sacrament is a memorial for Christ’s original sacrifice, an offering of praise to God, and a making-present of Jesus’ body, blood and spirit.38

The Eucharistic audience is subject to several temporal conflations – those of the moment Christ left the earthly plane, the present moment wherein we are in the company of the invisible Holy Spirit aspect of God, the promise of Jesus’ body becoming flesh again in communion, and the coming again of Christ in the most unpredictable way “in the end” – without being able to witness any of these manifestations, except through the theatrical ritual practice. The congregation, in the same eskhaton as those at that Last Supper, are continually in a process of anticipation or deferral of the visible arrival of Christ, who is fragmented into several aspects of the same invisible God, a God who came, disappeared mysteriously from a tomb, is ostensibly here (though we can’t see him), and will come again. Surely these multiple aspects of the same God and the simultaneous temporalities the church inhabits during the Mass assure that God is not locatable as either actor or character. The temporal structure of the liturgy, as informed by dramaturgical elements which include what is shown and what (Who) is not, ensures that the audience is caught, not in the suspension of disbelief, but in the attention to belief – the failure of the arrival of God in any visible way assures that the Eucharistic congregation remains in a state of messianism. They are caught in the anticipatory suspension that characterizes faith. Leaning into what may come, without guarantee of arrival.

For all that it shows, the Mass never reveals its best actor. The Catholic liturgy presents an abundance of artifice in lieu of demonstrating God’s real presence. And in Catholicism, the “great mystery” is that the seemingly absent elements are the most real, the most present. God is not just an actor who refuses to show up to rehearsal. He is the show, just without showing himself. We are a long way from Lanciano’s material proof of Christ’s presence. Certitude is not communion’s guarantee. In fact, the Eucharistic theatre is not so much a liturgy for blind belief, but rather a theatre in which all dramaturgical signs point one way and lead another, in a play of concealment and revelation. Faith, in the theatre of the Eucharist, is incited by the confusion of dramaturgical designations and by the presentation of artificial visual elements that manifest an invisible reality. Artifice aligns to make present the unrepresentable.

God, the star of the liturgical show, never shows up. The failure of the performative utterance “This is my body” to actually produce an adequate prop makes the This of, “This is my body” even more suspect. The requirement of the priest to play Jesus and the manner in which he does so can only embellish God’s absence. The distancing effects of actors, props and script in the Eucharist create a necessary level of sensory and cognitive disbelief. It is precisely these dissonances that incite the believer to faith.

The miracle at Lanciano is pretty incredible. That radical uncertainty can be produced every Sunday is extraordinary.

- Istituto San Clemente I Papa e Martire / Real Presence Eucharistic Education and Adoration Association, Eucharistic Miracle of Lanciano (2006), 1. ↩

- Istituto San Clemente, “Eucharistic Miracle,” 1. ↩

- Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2nd ed. 1376, 1413, accessed June 9, 2017. http://www.vatican.va/archive/ccc_css/archive/catechism/p2s2c1a3.htm ↩

- Istituto San Clemente, “Eucharistic Miracle,” 1. ↩

- Joy Palacios, Preaching for the Eyes: Priests, Actors, and Ceremonial Splendor in Early Modern France (University of California Berkley: Dissertation, 2012), 1. ↩

- Palacios, Preaching for the Eyes, 1-2. ↩

- Jean-Luc Nancy, Corpus, (New York: Fordham University Press, 2008), 3. ↩

- Nancy, Corpus, 3. ↩

- Nancy, Corpus, 3. ↩

- See Matthew 26, Mark 14 and Luke 22 for the scriptural accounts of the Last Supper. ↩

- Paul Bradshaw, Eucharistic Origins (London: Oxford University Press, 2004), 99. ↩

- Bradshaw, Eucharistic Origins, 13. ↩

- Bradshaw, Eucharistic Origins, 100-01. ↩

- Because of his anti-theatrical prejudice, it would have been most interesting, for the purposes of this artcile, though perhaps beyond its scope, to investigate the Eucharist as it occurred in Tertullian’s day. Though information about this period is obscure, Tertullian does write about the Eucharist, but less in terms of form. He is more interested in situating it in relations to Old Testament scriptures about blood and body (Bradshaw, Eucharistic Origins, 95). ↩

- Bradshaw, Eucharistic Origins, 139. ↩

- Bradshaw, Eucharistic Origins, 118. ↩

- Written from memory, with the help of online missals and Adolph Adam’s The Eucharistic Celebration. ↩

- Sometimes, members of the congregation take the roles of “communion ministers” and give the consecrated bread to be eaten to other parishioners. A thorough investigation into the dramaturgical effect of the proliferation of the priest’s role to a few parishioners lies beyond the scope of this article. ↩

- Adolf Adam, The Eucharistic Celebration: The Source and Summit of Faith (Collegeville: The Liturgical Press,1994), ix. ↩

- Adam, Eucharistic Celebration, 53. ↩

- Adam, Eucharistic Celebration, 54-5. ↩

- Bertolt Brecht, “On Chinese Acting,” translated by Eric Bentley in The Tulane Drama Review 6.1 (1961): 130–136. ↩

- Brecht, “On Chinese Acting,” 131. ↩

- Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2nd ed. 1375, 1413, accessed June 9, 2017. http://www.vatican.va/archive/ccc_css/archive/catechism/p2s2c1a3.htm ↩

- Domenico Pietropaolo, ‘Whipping Jesus Devoutly: The Dramaturgy of Catharsis and the Christian Idea of Tragic Form’, in Beyond the Fifth Century: Interactions with Greek Tragedy from the 4th Century BCE to the Middle Ages, ed. Ingo Gildenhard and Martin Revermann,(Berlin/New York: Verlag/de Gruyter, 2010), 404. ↩

- Pietropaolo, “Whipping Jesus,” 404. ↩

- Obviously, the passion plays predate Naturalism proper, but one could still say that they resist straightforward imitation, a stylistic feature thought through by Plato, Aristotle, Horace and others since antiquity. ↩

- “The Council of Trent followed the uninterrupted tradition of faith when it described this (the presencing of Christ through communion) as a ‘re-presentation’ of the one sacrifice of Christ that places it into the present as a contemporary reality” (Adam, Eucharistic Celebration, 65). ↩

- Here, we are a long way from Plato’s assertion that the original is superior to its copies and repetitions, since here the original is exactly re-produced via the copy. ↩

- Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2nd ed. 1375, 1413, accessed June 9, 2017. http://www.vatican.va/archive/ccc_css/archive/catechism/p2s2c1a3.htm ↩

- Nancy, Corpus, 5. ↩

- Nancy, Corpus, 5. ↩

- Adam, Eucharistic Celebration, 58. ↩

- Nancy, Corpus, 13. ↩

- Adam, Eucharistic Celebration, 65. Italics mine. ↩

- Giorgio Agamben, Language and Death; The Place of Negativity, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1991), 28. ↩

- Obscurity, Burke told us in the eighteenth century, is the first condition of the sublime. He writes, “To make any thing very terrible, obscurity seems in general to be necessary” (Burke, Edmund, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful [London: Oxford University Press: 1990 ↩

- Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2nd ed. 1322-1419, accessed June 9, 2017. http://www.vatican.va/archive/ccc_css/archive/catechism/p2s2c1a3.htm ↩

2 Comments