Click here for the Table of Contents

by Peter Murphy

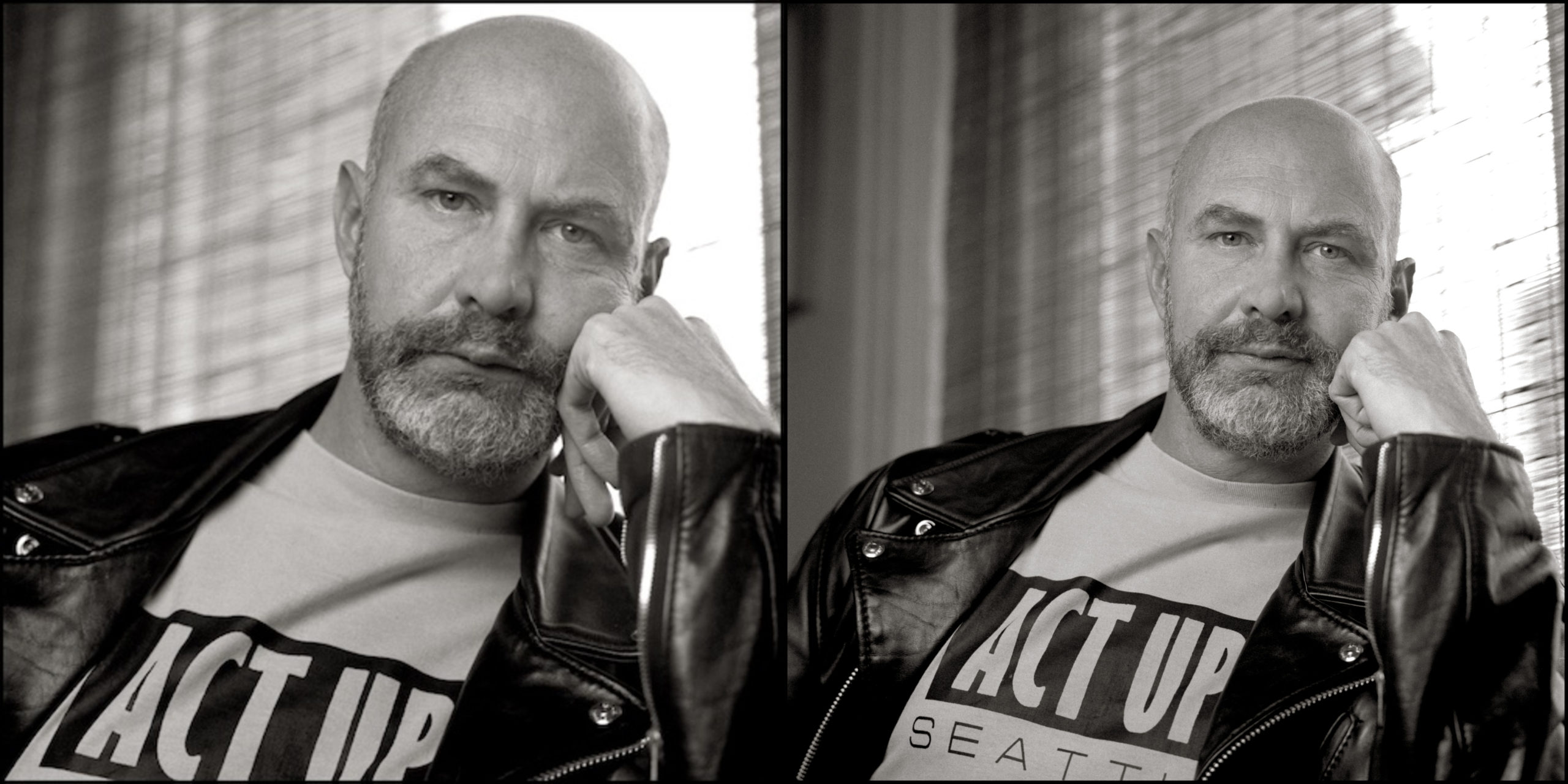

Featured images: T.L. Litt, Douglas Crimp, New York, 1990. (L) and Douglas Crimp, New York, 1990. (R). Images courtesy of the artist.

When it was time to decide the topic for Issue 33 of InVisible Culture, there was no question that it would be on anything other than Douglas Crimp (1944–2019). Douglas—someone who hardly needs an introduction, especially in the context of IVC—was an important figure for the journal and its affiliated graduate program in Visual and Cultural Studies. His pathbreaking essay “Getting the Warhol We Deserve,” for example, was published in our first issue. We would be remiss, however, to neglect to mention that Douglas was influential for an array of people and things: art history and criticism, queer theory and activism, gallery and museum exhibitions, and so many friends, students, and readers of his work. Given this vast network, our call for papers and artwork that engage with his legacy was a slight misnomer. There is no singular legacy to Douglas Crimp; instead, like his beloved New York City, there is a vibrant, shimmering grid of legacies, histories, and legends.

Rather than follow one route for honoring a beloved teacher, mentor, and friend, “After Douglas Crimp” shows a web of lines that weave, cross, and split from one another. Included in this issue are articles that use Douglas’s scholarship as a framework for analyzing art and culture, a collection of responses from his friends, colleagues, and students to a questionnaire, a digital poem that examines image reproduction and identity, a short film about Douglas’s attempt at making a cookbook, and three experimental pieces for our Dialogues section. Many of these contributions come from individuals who knew Douglas on some personal level, while the others point to the way that the majority of people came to know him (i.e. his writing). Therefore, this issue of InVisible Culture presents a rigorous intermingling of the personal and the professional, sometimes indistinguishable from one another, that Douglas perfected throughout his career.

We were reminded upon writing this introduction that it has been over two years since Douglas passed away. We want to ask ourselves if it has really been that long, but we already know the answer. Instead, we might ask why it sometimes feels like we just received the news. Or why, at other times, it feels like the news never happened and we can still reach out to him. These lapses in temporality and judgment are, as Douglas would surely remind us, intrinsic to the work of mourning. Mourning shrinks and expands, divides and multiplies; Douglas taught us this many years ago. Freud posits that at an unforeseen point, mourning does conclude. But what comes after? Douglas isn’t here to answer that for us, but, as our contributors can surely attest, he showed us how.

In “The Haunting of a Modernism Conceived Differently,” Matthew Bowman reexamines some of Crimp’s groundbreaking essays published in October that established postmodernism as a crucial theoretical concept answerable to recent developments in art and its criticism. He discusses how categorial separations that are thought to be integral to modernism (e.g. medium specificity and teleology) are undercut in Crimp’s proposal of a “modernism conceived differently” that figuratively haunts his theorization of postmodernism. Bowman seeks to recover the relation of postmodernism to this alternative modernism in several examples of Crimp’s influential scholarship. He aims not to treat this other modernism as an intellectual aberration, a failure of argumentative consistency, but rather to spotlight its critical fecundity and its betokening of Crimp’s early interest in deconstruction.

Theo Gordon’s article “Re-reading ‘Mourning and Militancy’ and its Sources in 2021” examines how the intellectual force of Crimp’s canonical essay partly derives from its selective use of sources. As Gordon notes, “Mourning and Militancy” (1989) has proven fundamental to the study of contradictory affects and ambivalence in AIDS activism, even as it draws selectively on a range of source texts like Simon Watney’s Policing Desire (1987). Following Crimp’s critical examination of ambivalence and Watney’s study of the plight of heterosexual parenthood in the AIDS crisis, Gordon analyzes how Russell T. Davies’ British television AIDS drama It’s a Sin (2021) reinforces problematic tropes of femininity and the maternal in the context of an epidemic that the series imagines as only afflicting gay men.

In “Manhattan-Hanover Transfer,” Lutz Hieber and Gisela Theising take us to New York City in 1988, where their first encounter with the New York art world gave them a new perspective on art and activism that was markedly different from what they knew in Germany. After visiting the ACT UP exhibition at White Columns in 1988, Hieber and Theising began planning an ACT UP exhibition of their own. This led them to meet Crimp in 1990, and he helped the authors collect material for exhibitions in Germany on the activist group. As a result, works by New York artists affiliated with ACT UP not only became recognized but also circulated widely in Germany. This also triggered forceful debates amongst German art scholars, which was supplemented by support from Crimp in publishing work that continued to introduce his ideas to the social sciences in Germany. As Hieber and Theising reveal in prose that is both personal and critical, the expansive sense of community that Crimp identified in ACT UP reached beyond the New York art world to international discourses and communities.

In “Mourning, Militancy, and Mania in Patrick Staff’s The Foundation,” Christian Whitworth analyzes Patrick Staff’s 2015 video installation The Foundation, which restages the Tom of Finland Foundation in Los Angeles as a site of intergenerational responsibility for the curation of queer identities and histories. As Whitworth notes, Staff choreographs awkward experimental dance sequences within a fabricated set to reconcile a trans-feminine identity with the Foundation’s masculine comportment. One sequence manifests an extension of melancholic and militant mourning spelled out by Crimp during the rise of the AIDS epidemic. He argues that Staff’s performance illustrates a form of “manic mourning” which seeks new modes of queer passing, a difference marked neither by reverence nor irreverence for but rather an attraction over and beyond the paradigmatic structures distinguishing histories of queer subcultural generations.

The featured artwork for the issue is Cindy Hwang’s “Thirty-six Copies of the Mona Lisa.” Broadly speaking, the work is a digital poem about Chinese national identity, oil painting reproductions, and Western colonialism. When Hwang originally made Thirty-six Copies in collaboration with Cynthia Hua, she was not thinking about Crimp and his work. However, her recent engagement with his seminal essay “Pictures” led her to revisit and reconsider Thirty-six Copies through the pictorial conceits articulated in his essay and produce the work included here. Following Crimp’s postmodern theorization of representation, Thirty-Six Copies exists in a generative gap wherein the relationship between picture and text is sometimes indeterminate, loosely associative, or more complex than initial appearances might suggest.

Dialogues, the section where we publish exhibition reviews and experimental texts, features three contributions that examine the influence of Crimp in varying modes. Benjamin Haber and Daniel J. Sander follow a Crimpian analytic model to analyze past and present representations and conflations of pandemics. Meanwhile, Xiao (Amanda) Ju performs a reading of a chapter from Before Pictures to meditate on the ways reading opens channels of communication. Finally, Peter Murphy provides reflective descriptions of the courses he took with Crimp at the University of Rochester.

Issue 33 includes a special insert devoted to more personal reflections on Douglas. In addition to our call for papers, we solicited responses from Douglas’s friends and colleagues to a questionnaire written by IVC’s editors. The scope of the questions (which are included in the issue) range from the private and the political to the serious and the witty. Given this spectrum, we received a variety of responses that adhere to the mixture of reflection and criticism that was intrinsic to Douglas’s writing. The contributions reveal Douglas in many guises: from the ACT UP activist shopping for an outfit to wear to the Sydney Gay & Lesbian Mardi Gras Festival to the timid yet assured scholar buying his first car late in life; from the curious researcher in the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center to his signature in New York City gallery logbooks. Like the peer-reviewed articles in this issue, these personal responses attest to the multiple ways Douglas and his legacies have held and will hold influence over the lives of others.