Featured image: Patrick Staff, video still from The Foundation, 2015. Courtesy of Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles.

He was a damned good-looking guy, all right—and in that outfit he looked rugged, too. I reckon he was about twenty-four, and so well made that he just escaped being pretty. His black curly hair tumbled out beneath the peak of his motorcycle cap, pushed to the back of his head. […] The planes of his face from cheekbone to jawline were almost flat, perhaps a little hollowed, so that he gave the impression of a composite of all the collar ads, fraternity men, football and basketball players, and movie heroes of the contemporary American scene.1

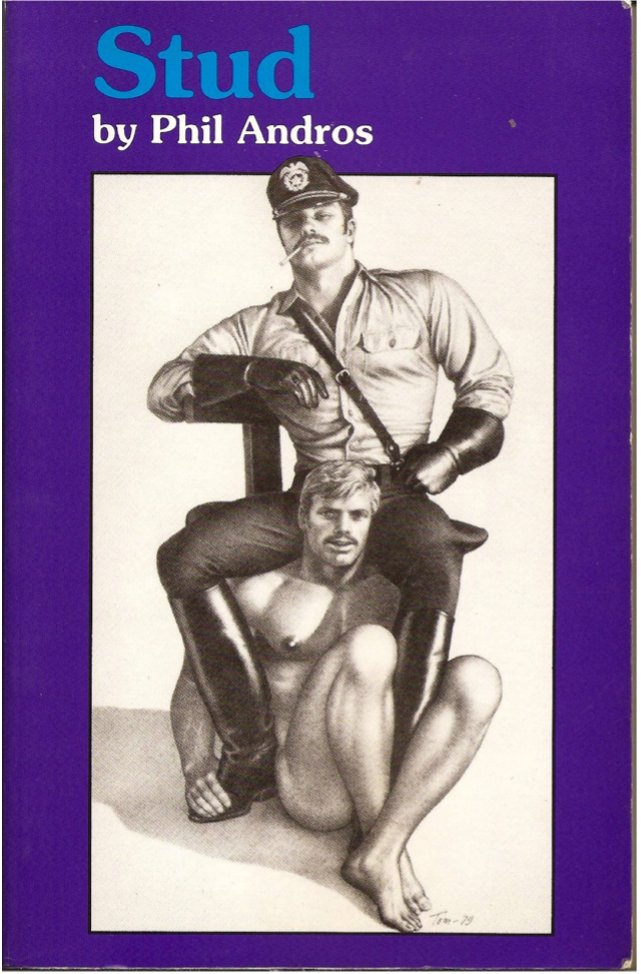

When the novelist, poet, and university professor Samuel Steward, working under the pseudonym Phil Andros, published in 1966 his erotic collection of short stories, Stud, he ushered forth a composite image of homoerotic fantasies, its model masculinities who, like the hum of their motorcycles and movie projectors, remain throbbing throughout. And if the seated man on the cover of the 1993 reprint (fig. 1) serves as a perfect “composite” of the many men encountered (to put it lightly) within, so too must he and his angled cheeks form the “logical” apotheosis of the scene of American homosexual desire: huge, hung, and strapped in leather, yes, but more importantly, white, male, and domineering. This 1979 illustration by the homoerotic artist Tom of Finland (Tuoko Laaksonen, 1920-1991) exemplifies an image of gay virility which persists even in the wake of the artist’s passing. His form, then, is bothcomposite and prescriptive, both embodying and extending a normative model of queer masculinity.2 But in keeping with the strictures of his disciplinary fetish, he enables and invites various forms of deviance. Like the naked hustler trapped in the prison of the cop’s clenched thighs, we might be tempted to wiggle free and misbehave.

When the transgender, London- and Los-Angeles-based video artist Patrick Staff (they/them) checked-in at the Tom of Finland Foundation from 2012 to 2015, they confronted this image of overt masculinity, screening the sadness and pain, embarrassments and anxieties central to a history of queer mourning. The Foundation, a twenty-eight-minute video essay combining meditative observation with highly produced stage performances, pictures the pleasures and displeasures of a queer archival practice steeped in a historical materialist melancholy, a longing for the loss of both Tom and his aforementioned popular composite. In one early scene (fig. 2) viewers see Staff seated before the foot of the bed, flipping through a small selection of Tom’s ephemera with one of the foundation’s contemporary caretakers, a mustached gay man who traded the sleek black leather gloves of the artist’s illustrative fantasies for those more wrinkled, white, cotton ones of the archive. On the bedroom’s walls behind them hang a selection of Tom’s boys, each finished with a typical hyperrealist tone exhibiting in full detail the big-dicked, burly, interpenetrating men. But the exchange below, between Staff and the caretaker of the house museum, is more reserved. The latter, in turn, relays, with a hint of nostalgia and a few furtive glances, a history of the foundation and the 1920s craftsman-style home in which it has come to reside.

Founded in 1983 by Tom and friend Durk Dehner as a place from which to manage the copyright and sales of the artist’s illustrations, it has since operated as a library, museum, historical site, and community center. Weekly life drawing sessions bring together the neighborhood’s gay men, who reconstruct in close proximity to one another as well as the home’s numerous decorative dildos that selfsame sketch of masculinity with which the foundation was established and for which Tom has by now become synonymous. From his first published appearance in the spring 1957 issue of Physique Pictorial to his death in 1991, Tom’s illustrations have taken as subjects soldiers, sailors, cops, and leather-clad bikers. Despite (or because of) the incredibly detailed renderings of these male forms, Tom never hesitated to exaggerate their endowments. As a result, Tom of Finland has become representative of an era of more symbolic integrations between gay pornography and artistic production, between public acceptance of private pleasures, making his legacy a cause of communal celebration to this day.3

Yet the foundation, grappling with the evolving politics of queer identities, faces the challenge of its own historical re-narration: how can it serve as a home to a wider range of queer, trans, fem, raced, and disabled identities while still exhibiting the white, militant, masculine virility in which each of its walls has steeped since the early 1980s? Indeed, any such contention written into the intersectional ethics of generational “passing” may too easily slip into essentializing defamation.4 My aim, like Staff’s, is not to gloss over the temporal and contextual intricacies between queer generations, especially when the boundaries between them are more muddled than clear-cut. The temporal distinctions demarcating the dire realities of the AIDS crisis, to be clear, seem to perpetually include the present. Reexperiencing and renegotiating the pain and trauma of mass loss distinguishes the closure of nostalgia from the unbounded duress of “chronicity,” what Marc Arthur describes as “a temporality in which illness is ongoing rather than a climactic event of mortality.”5 Moreover, illness is not the only cause of queer loss. The annual Transgender Day of Remembrance so forcefully evokes the violence faced especially by trans people of color through its continual recognition of the names of loved ones lost to homicide.6 Gathering and naming the deceased serves to weave together an intergenerational fabric of queer and trans solidarity. As C. Riley Snorton and Jin Haritaworn foreground in their essay on “trans necropolitics,” “trans death opens up political and social life-worlds across various times and places,” solidifying connections across rather than distinctions between categories of history, experience, and ideology.7 Still, the screened relations between Staff and the foundation present, I think, a fruitful reconsideration of a responsibility to “a generation largely constituted of the dead” that tells a story of neither recovery nor refutation but an embodied attraction over and beyond the paradigmatic structures separating queer subcultural histories.8

This is “the work of mourning” that Douglas Crimp employs in a polemic against AIDS activists’ enforced opposition between militant action and the passive psychological sadness as well as pain often subtending such efforts.9 The “necessary and difficult” work of writing in the wake of widespread violence and loss, Crimp affirms in his 1989 essay, “Mourning and Militancy,” supports not merely the socialization of queer life but also and importantly the psychic conditions adhering the individual to the generational collective.10 Writing in the midst of widespread deaths due to complications with HIV-AIDS, ACT UP meetings, candlelight vigils, and incessant vitriol from queer and heteronormative media campaigns alike,11 Crimp emboldens the affectual relations of a community at once grieving for the dead and raging against a failed or even counterproductive government response.12 Yet the psychological underpinnings bridging grief to activism are more complex. Taking note of Freud’s account of the process by which individuals overcome loss through mourning, there remains a recuperative political potential in Crimp’s own definition, an active and transformative withdrawal and redirection of libidinal energies away from the “missing object” of the beloved toward the militant moment necessitated by a confrontation with reality.

It is melancholia, the pathological persistence of mourning, which sustains for Freud and Crimp alike the dangerous fall into moralizing self-abasement. For, rather than the political work of reality, the subject of Crimp’s queer melancholia directs the libidinal cathexes of loss toward the ego itself, making oneself, and not the world, “poor and empty.”13 In a move that seemingly aligns with ACT UP’s antithetical stance to mourning, Crimp decries this protracted sadness as a willful submission to popular media’s mythical moralism and self-incrimination. “I only want to draw an analogy,” he writes, “between pathological mourning and the sorry need of some gay men to look upon our imperfectly liberated past as immature and immoral.”14 While it may seem as though Freud’s titular binary maintains its structure within Crimp’s political cooptation, a more nuanced interpretation evidences the complexity of the latter’s scholarly sensitivity, no doubt a result of his stance between art and activism. As Crimp argues, mourning’s “particular pain” should not be the slippery slope toward melancholia’s self-loss. But this is not to discount mourning itself, nor the prolonged process through which it is felt. Rather, Crimp’s aim is to redirect the negative feelings away from self-infliction and, with it, self-moralization:

Frustration, anger, rage, and outrage, anxiety, fear, and terror, shame and guilt, sadness and despair—it is not surprising that we feel these things; what is surprising is that we often don’t. For those who feel only a deadening numbness or constant depression, militant rage may well be unimaginable, as again it might be for those who are paralyzed with fear, filled with remorse, or overcome with guilt. To decry these responses—our own form of moralism—is to deny the extent of the violence we have all endured; even more importantly, it is to deny a fundamental fact of psychic life: violence is also self-inflicted.15

Thus begins an amplification with which Crimp’s essay ends: a defense of the death drive and the profound negativity which joins mourning to militancy and militancy to mourning.

Crimp’s negative assertion remains a welcome rejoinder to twenty-first-century discourses misconstruing melancholia’s negative pathology as productive positivity. A published collection of essays of which Crimp’s later “Melancholia and Moralism” is a small selection finds the editors David L. Eng and David Kazanjian imputing to their titular loss “a creative instead of a negative quality.”16 Transforming the isolated individuality of Freud’s original diagnosis into a collective politics of remembrance reclaims, according to the editors, “the politics of mourning […] as that creative process mediating a hopeful or hopeless relationship between loss and history.”17 But as film scholar Eugenie Brinkema points out, in this shift “melancholia comes to take on every positive conceptual attribute previously denied it: as a projective reach into the historical totality that precedes an individual or society far from the introjective ambivalence and solipsistic suffering of Freud’s earliest treatments.”18 In other words, melancholia’s pathology has become normalized as a productive mediation, even dialecticization, between a historical passivity and a future potentiality. Even the deepest of despairs is now put to work, sublated, rendering a return to Freud’s and Crimp’s writings on loss itself as a sort of mourning for the loss of melancholia. Still, might there be a way to follow through on this mediation, exalting in the promise of relief from the recursive loops of Freud’s painful attachments, while still recognizing the private, negative passions following in melancholia’s wake? Moreover, how might these mourning rituals relay the queer relations among individuals and communities intergenerationally distinct yet contingent? And lastly, might various forms of aesthetic mediation assist in marking intergenerational time and picturing the expanded duration demanded by these nuanced affectual dimensions of loss? These are the questions with which Staff, by way of Tom, extends the debate on mourning and militancy across scales both personal and political, present and historical, individual and collective.

Like Freud’s, Crimp’s essay is an expansion of the concept of mourning to encompass the loss of not just a loved one but also valued abstractions.19 Notions of life and death are widened within the author’s definition to include “a culture of sexual possibility: back rooms, tea rooms, bookstores, movie houses, and baths; the trucks, the pier, the ramble, the dunes […] golden showers and water sports, cocksucking and rimming, fucking and fist fucking.”20 And while Crimp’s interpretation of Freud’s “loss of some abstraction” at the heart of mourning focuses on the disappearance of shared sexual desires sustained generation after generation, a small note surveying the crowd of one ACT UP meeting redirects his readers’ attention to the historical disparities distinguishing the constituents themselves. “I am struck,” he recounts, “by the fact that only a handful are of my generation, the Stonewall generation. The vast majority are post-Stonewall, born hardly earlier than the gay liberation movement itself….”21 The lost object of The Foundation’s mourning appears equally to be an entire generation, urging us to reconsider in the present “passing” of queer histories the host of emotions to which Staff’s mourning gives rise. Such emotions may be inclusive of, but by no means limited to, Freud’s melancholia or Crimp’s militancy. Identifying still others requires a special mode of feeling for the subtleties in Staff’s performance, where intricate layerings of affect sustained under the guise of dislocation afforded by observational cinema ripple to the fore along the same complexes as either melancholia or militancy. But as I hope to show, the dance between the life and death drives, between the instincts toward preservation and destruction, result in what I call, building on Crimp’s close reading of Freud, a form of “manic mourning” whereby the subject fulfills a temporary liberation from the lost object as the cause of their suffering, only to risk sudden re-attachment in the return of the generational collective’s incomplete mourning ritual.

These distortions between queer generations and their respective categories of experience, their “intuitive” forms of knowledge “in a queer time and place,” are not so easily recognized in the variegated forms of video art, at least in these particularly stoic scenes.22 Defining Staff’s personal political relationship to the men housed within the foundation follows no easy, conclusive path. As Staff reflects, “to say that I’m trans, but to also be assigned male at birth and presenting as pretty masculine, I can be seen as a kind of dilettante, or just a man playing with ideas. It’s a very particular gap, and one that actually a lot of people exist in. Society grants us very little freedom in our gender.”23 But Staff’s trans identity rubs up against not only the masculine comportment of the foundation, but also Tom’s archival cataloguing system, which still exists within the walls of the original home. The camera approaches first the foundation’s communal activities and the decorative whips, chains, and dildos of Tom’s room through lingering mediations before surveying the banality of the house’s cataloguing system. One shot, for example, exhibits shelved albums of erotica clippings, each bound in leather with gold horizontal lineaments tying together their spines, one after the other (fig. 3). But behind such playfully alliterative labels as “megacosmic models,” “magnificent men,” or “hairy hunks” hide the symptoms of the archive: process of counting, ordering, and reordering which seek to homogenize the undeniably ruinous nature of the museum.24 The effect is, importantly, temporal. Straight time is restored as a record of restoration and completion, an assurance of continuity, regulation, protection.

Art historian Andy Campbell calls into question the recontextualization of Tom’s work within a museological sphere, challenging the supposed dichotomy between, on the one hand, the drawings’ intended liveliness and social animacy, and, on the other, the archive’s dusty mummification.25 Rather than propagate such a dichotomy, Campbell argues, Tom’s work invites a re-conception of the space of the (domestic) museum archive as through and through erotically charged, “a shared point of contact in the scene of erotically networked relations.”26 These men passing in and out in regular, daily succession form a communal network seemingly inspired by the mutual love and support subtending Tom’s work. “Here,” Campbell tells us plainly, “people eat, drink, sleep, fuck, and fight among the prints, collages, original drawings, and leatherwear that Tom produced and owned.”27 The interactivity of bodies and archival materials continually reanimates the archive and its generational transmission of knowledge. Of course, a “queer historical impulse” offering connections both personal and communal may afford the artist-as-researcher some much needed protection, especially when, as Carolyn Dinshaw reminds us, traditional boundaries of knowledge production tend to exclude the amateur and the fan.28 Adopting this historical turn seeks transhistorical lineages of queer identities in order to make visible and viable the very categories within which subjects situate themselves.29 Yet the challenge of historical specificity always rubs up against Foucault’s oft-cited discursivity of sexual norms, by now a well-heeded warning within queer theory purporting instead the historicity and contingency of categories both sexed and gendered.30

And yet the archive is not so much the subject of Staff’s film as the irregularities of its reperformance, first hinted at with the grating contrast of film grain, and the relative incoherence of a vernacular image. Intercutting Staff’s more polished, daytime meditations are handheld observational sequences drawn from the darkened recesses of Tom’s birthday party, an annual fundraiser and celebration of the now sanctified artist (fig. 4). Through the flickering light of birthday candles, the intermittent flash of a camera, and the beam of a 16mm projector screening vintage gay porn, we see semblances of an apparatus’ past continually transferred into Staff’s present through a process film scholar Pavle Levi refers to as “retrograde remediation”: “instances of remediation distinguished by some inherent discrepancy, by a pronounced practical/technological inadequacy of one (‘older’) medium to fully assimilate certain aspects of another.”31 Thus, Staff’s play with amateur form of video recording mirrors the artist’s more personal failures of assimilation. Layered atop the aging forms of the filmic apparatus are the social bodies that animate them, literalized here by the bearer of the birthday cake intercepting the projection of a couple of young lads casually 69-ing. And however much the celebration seeks to record the unidirectional movement—that straight time—of their collective temporality (i.e. the growing one year older), Staff’s retrograde remediation reasserts the transitory nature of the event that, as Elizabeth Freeman shows, “binds” queer subjects through temporal transitivity to their pasts.32 Staff’s camera captures this moment of convergence, in which layers of older and newer machinations never fully assimilate, and the bodies of their operational actors, like the couple 69-ing, never “properly” align.

These improper anachronisms warn us, moreover, of the risks in tracing the means by which conceptual circuits find their concrete material-technological supports. For the linking of concepts to bodies inevitably establishes norms, identifies artifacts, and maps routes of deviancy along which transgressors might be named.33 Staff’s “queer archaeological” method within the walls of the foundation’s cataloguing systems foregrounds the deliberate contextual and temporal clashes symptomatic of many an archival practice. Transgender and gender non-conforming bodies once purposefully excluded from the materials and thus matterings of the archive are here retroactively reinserted, but not without fault. The Foundation serves as a timely reminder of the dangers of designating transgender and gender non-conforming persons as distinct psychobiological types and archival categories. What Nancy Ordover calls the “myth of liberatory biologism” situates queer bodies within a biological determinism organized along a linear chronology of causation theories.34 To claim a hereditary construction of homosexuality or transgender identity upholds biological truths aimed at normalizing difference and reinforces eugenic ideologies used in the justification of “naturalized” forms of discrimination. The geneticization of sexuality and gender, for Ordover, interiorizes difference and contradiction, laying the foundation for eugenic ideologies in other contexts. How, then, do we make sense of the chronopolitical backdrops against which The Foundation layers its queer subjects? Though it may immediately appear to actualize the violent histories of “progressive sciences” through an adoption of its temporal layerings of difference, the film installation disorients and denaturalizes these dominant ideologies by holding histories not in harmony but rather estrangement and discord. Figuring the failure of memory in the awkward juxtaposition of queer generations, Staff moves beyond any traditional distinction between textual archives and embodied remembrance.

In this way, The Foundation serves as an imperative to surpass corrective tendencies bespeaking perfectible images of queer community, in which liberation is perpetually deferred. Seeking instead the productive failure of memory, one which considers the “ethical chance that may lie with getting it wrong,”35 supports the reanimation andreassertion of a history’s demise, all the while uncovering the presence of a particular bodily being wherein observational images espouse a connection to the materiality (and thus “matter”) of queer bodies, perception, and subjectivity. The Foundation provides us with an extension of Crimp’s theoretical foundation, a refocusing of Freud’s death drive through the lens of queer history in order to comprehend how violence is directed not only externally but also internally, and thus “to confront ourselves, to acknowledge our ambivalence, to comprehend that our misery is also self-inflicted.”36 The flag of queer futurity no longer flies a rainbow for redemptive temporality but rather hangs at perpetual half-staff in recognition of what Lee Edelman terms an “epistemological self-destruction”: “a nonteological negativity that refuses the leavening of piety and with it the dollop of sweetness afforded by messianic hope.”37 Yet for all its deadening consistency across the appearance of generational divides, this self-inflicted queer negativity orients the disciplinary pleasures of Tom’s toys toward an ever-arriving future.38

Between Tom of Finland, The Foundation, and its diverse community extends, much aligned with the interests and imagination of their shared leathersex communities, a “signifying chain,” or a linking of signification Lacan understood to be not a conscious recall but an unconscious performance of memory.39 Dildos, dog collars, cock rings, shackles, hoods, altars, and offering cups join such chains in signifying throughout the film the materialization of Tom’s memories as both style and ritual. Yet Staff adopts a refracted form of their historical predecessor. Key here are the ways in which the “dialogue” between respective temporalities operates on the plane of aesthetics as a rhetoric of style. Evocations of Dick Hebdige’s Subculture: The Meaning of Style are in keeping with Tom’s historical moment. Together, Dick and Tom unveil the ways in which leathersex claimed codes of dress to be “described, interpreted, and deciphered,” thereby determining the evolution of a subcultural form and the ideology “acted out” by its members.40 Indeed, Hebdige’s sociology concerned the mods, skinheads, punks, teds, and greasers of 1970s British subcultural youth. However, the ways in which such groups either extended or antagonized the Rastafarian sources of their appropriation informs also Staff’s succession of specifically queer subcultures. Still, a key difference must be untangled: whereas Hebdige fixes Rastafarian style as a signifier to be taken up, reinterpreted, and reinscribed, Staff supports a dynamic re-making of history altogether, with “representatives” of each generation engaged in not so much a reenactment as a re-creation of the relations between both.

These personal negotiations are staged not at the foundation but elsewhere, in a stripped-down reconstruction of the foundation’s living room, with its characteristic dappled Los Angeles light leaking through the blinds of the front window, which serves as a sort of Brechtian “learning play” (Lehrstück) space in which the artist might explore the inter-subjective connections between themselves and an older, bearded gay man dressed in a long smock, a cut-off t-shirt, and a heavy silver chain around his neck.41 As the two reconstruct the room on a soundstage, a camera intercuts long tracking shots around the perimeter’s scaffolding with close-ups of laborious bodies-in-motion. But only after they carry on stage a small set of archival storage boxes which they, in turn, stack in the corner of the rudimentary room, do they assume their positions and re-orient themselves. Shortly thereafter, a choreographed dance ensues between the two generations of queer identities and ideologies, their parallel movements set to an electronic shuffle drawn from the collection of the foundation’s club records (fig. 5).

A medium close-up direct address with the older bearded man, now bathed in a warm orange light, initiates the scene. “Treat this place as your…” he pauses, wearing a slightly furrowed look on his brow, “…community center.” The video fades to black before transitioning to a long shot of the room, here demarcated by metal scaffolding supporting cool white stage lights. He stands at a slight remove in the opposite corner of the stage, though his comportment and angled approach matches precisely Staff’s. As a series of syncopated electronic kicks begins to echo throughout the space, a cut-in shows the two first raising, in unison, their left arms to a ninety-degree angle before inverting the positions of their hands so that their palms face upward. They lower their arms altogether, signaling the completion of the first step of an increasingly complex, albeit always rudimentary, dance sequence. The camera alternates across diverse perspectives of the stage and its performers, choosing to picture the two either from afar in a moment of relational pedagogy or in a voyeuristic close-up fetishizing the undulating bodies on-screen. In one curious shot, the camera tilts upward along Staff’s chest, completely bare save a black leather harness wrapped around their shoulders. Should the direct address with which the sequence began intimate the shared play of not just the performers’ but so too viewers’ gazes, Staff here not only invites but pleasures in the invitation of those same processes of bodily circulation, display, and reception at the heart of Tom’s work. Artist Nayland Blake writes of this playful coercion while referring to a typical orgiastic Tom scene which centers within its frame multiple men fucking while reserving still others for observation from the margins: “This allows for a double current of attraction/participation rather than the single current of gazer/object of the gaze. No longer interested in desire and its implied lack, Tom substitutes a pleasure of looking and being looked at, equating the cruising look with the sexual act.”42 The final consummation of the two generational representatives comes with a quick jump from a squatting position and a synchronized swinging of the arms, a perfect unification of bodies and their sexual proclivities.

In synchronizing their dance movements—a series of simple sways and steps—the two evidence the conformity seemingly necessitated by the image of Tom’s perfectionism with which I began. Staff’s adoption of the militant comportment constitutive of Tom’s hypermasculinity assists in, however ironically, severing the bond that once sustained the artist’s melancholic attachment to the “lost abstraction” of the preceding queer, subcultural generation. What Catherine Spencer calls the “pedagogies of performative afterlife” describe a process whereby a dominant/submissive relationship figures the latter so enchained and enchanted by the former that both find themselves, through discipline and direction, ascending to a higher self.43 But the passing of perfectionist partialities, I argue, need not always remain at a further remove, as the social democratic hope of inclusion. Such perfectionism is here materialized in the present as the temporary overcoming of melancholia through a momentary catalyzation, a choreographic integration revealing the fine line between melancholia and mania.

Nowhere in “Mourning and Militancy” does Crimp write of mania, despite Freud’s maxim that “the most remarkable characteristic of melancholia, and the one most in need of explanation, is its tendency to change round into mania—a state which is the opposite of it in its symptoms.”44 But as an extension of Crimp’s interpretation, an essayistic response in its own right, Staff’s The Foundation makes the necessary leap. Here, the passing of queer subcultural generations joins the passing from mourning into melancholia and militancy into mania. For, the synchronization of bodies representative of queer histories serves to expunge the threat of the loss, resulting in an excess of libidinal attachment to be performed as mania. Freud explains: “In mania, the ego must have got over the loss of the object (or its mourning over the loss, or perhaps the objects itself), and thereupon the whole quota of anticathexis which the painful suffering of melancholia had drawn to itself from the ego and ‘bound’ will have become available.”45 With this Freud, like Crimp, evades a discussion of mania’s aesthetic sensibility, citing its resistance to an investment in melancholic reproduction. Yet Staff’s video provides a glimpse into this index of the melancholic’s “joy, exultation, or triumph” over the lost object by registering the form of mania.46

The temporal dimension of the transition from mourning to militancy to mania takes shape both figuratively and spatially within this climactic scene. No longer a sequence but a simultaneity of generationally distinct queer subcultural histories, the bodies of its actors move about the space of the stage in all their gesticulating excess. Yet an aesthetic of mania cannot be interpreted by bodily expression alone; in fact, the stoicism of earlier scenes carries over into the choreography of assimilation. Rather, I interpret mania here as a successful dialecticization and overcoming of historical mourning through the mediation of not just dancing bodies, but also film, video, architecture, performance, and sound. Like the earlier birthday party scene, an entire media surround marks the historical drama, spatializing the dissolution of sequential temporality on stage and screen. Walter Benjamin formulates this spatialization in his analysis of the German Trauerspiel as a place “where heroic greatness meets its downfall, and the court is reduced to a scaffold,” as “a spatial continuum, which one might describe as choreographic.”47 In this light, the choreography of Staff’s dance proves to be not just the militant synchronization of moving bodies but so too the medial configuration of history’s dynamism.48

The image of a manic trajectory of mourning, however, is one that momentarily revels in the triumph over loss through the discharge of joyful emotion yet immediately begins searching for new connections of object-cathexes. Recognizing mania thus entails preparing for the slide back into melancholia. Judith Butler offers her own commentary on a choreography of mourning relishing in the pleasures of syncopation when she writes in her afterword to Loss, “After Loss, What Then?”:

the rituals of mourning are sites of merriment; […but] it is not always possible to keep the dance alive. If suffering, if damage, if annihilation produces its own pleasure and persistence, it is one that takes place against the backdrop of a history that is over, that emerges now as a setting, a scene, a spatial configuration of bodies that move in pleasure or fail to move, that move and fail to move at the same time.49

Mania is thus an incomplete mourning in oscillation with melancholia. Mania, of course, then, but mourning and militancy too: mourning, militancy, and mania.

The Foundation ends with a final appearance of the soundstage, this time rearranged in the rudimentary form of a bedroom, at the center of which begins to build a large mass of pink foam emanating from a machine often found as a recurring infrastructural feature of gay dance parties (fig. 6). Except now the boisterous scene of choreographed relations is reduced to an empty stage void of club music, the slow hum of the machine barely registering on the video’s soundtrack. As the formless cloud continues to grow, inching over the mattress, clothes, boots, and blank pieces of paper littered throughout, the camera cuts in to its deep ravines and towering peaks. A slow, handheld close-up tracking shot across the landscape of glittering pink bubbles dissolves, much like the dance between Staff and their other, any clear focal distinction between bodies, objects, and their respective histories. A fluid, queer melding of figures and forms finds its momentary maniacal apotheosis, a triumph over the loss associated with mourning. Yet it is, importantly, a momentary surmounting. The foam soon thereafter dissipates, leaving in its wake a damp wetness which warps and stains the objects below, like a pair of black leather boots evocative of Tom’s militant personas. Militancy and mania, this final shot asserts, turn out to be two sides of the same melancholic coin.

Perhaps, then, my anti-essentialist ultimatum and list of Staff’s mourning rituals from the outset of this essay might be a bit more refined. I take a cue here from Tavia Nyong’o’s study of an integrationist dance of different sorts: an “amalgamation waltz” investigating blackrepresentative space within memory through terms of a dialectical shuffling between essentialist impulses and anti-essentialist effects.50 Nyong’o helps us to visualize Staff’s practice as, in other words, an affective experiment situating a sort of queer separatism within a larger historical unfolding of queer integration and symbolic inclusion. And it situates the subject of Staff’s historical knowledge as the embodiment of this dynamic unfolding, their feelings of mourning and militancy as true and as just as their feelings of mania. “This performativity,” Nyong’o concludes,

interrupts complacent dreams of presenting the past as it was and, by placing the past in a parallax view with the present, establishes a friction rather than a fusion, a clash rather than a harmonization. It results in a representational space that is both black and, in a specific sense, negative, in that it cannot spell out a set of instructions on how to conduct ourselves in the present, but can only instruct against the presumption that its stories lie at the ready to be told.51

This is the performativity conveyed by the cover of Stud: that dominant/submissive, fort/da oscillation that insinuates a friction rather than a harmonization with the past, resulting in a perpetual release from the perfect prison of his clenched thighs, just as we seek to climb back in, and hold on tight.

Author’s note: This essay was developed with the assistance of Haley Hvdson, Andy Campbell, and my fellow panelists—Iris Pintiuta and Stephen Woo—at the University of Southern California’s 2020 First Forum conference, “Passing,” where this work was first presented. Special thanks to Peter Murphy, Jacob Carter, and the anonymous peer reviewer for their feedback and support.

- Phil Andros, The Stud (Washington, D.C.: Guild Press Ltd., 1966), 17. Emphasis mine ↩

- For the ways in which figurative forms and orientations of approach become normative, and the ways in which “queer” deviations serve to provide their own new forms of (dis)pleasure, see Jeremy Melius, “Sculpture from Behind,” in Photography and Sculpture: The Art Object in Reproduction, eds. Sarah Hamill and Megan R. Luke (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2017), 67-80. ↩

- For accounts on the history of Tom of Finland, see F. Valentine Hooven III, Tom of Finland: His Life and Times (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 1993); Micha Ramakers, Dirty Pictures: Tom of Finland, Masculinity, and Homosexuality (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2000); and Dian Hanson, ed., Tom of Finland XXL (Cologne: Taschen, 2009). ↩

- My use of the term passing here is multivalent. Not only does it suggest the sequential chronologies of distinct generations, but especially relevant for raced and/or transgender and gender non-conforming persons are the pleasures and problems of subjectivity, agency, and authenticity in passing. See especially Sandy Stone, “The ‘Empire’ Strikes Back: A Posttranssexual Manifesto,” in The Transgender Studies Reader, 1st Edition, eds. Susan Stryker and Stephen Whittle (New York and London: Routledge), 221-235; C. Riley Snorton, “’A New Hope’: The Psychic Life of Passing,” Hypatia 24.3 (2009): 77-92; and Sandra Harvey, “Passing for Free, Passing for Sovereign: Blackness and the Formation of the Nation,” PhD Dissertation, University of California Santa Cruz, 2017. ↩

- Arthur builds on the work of Elizabeth Freeman, who correlates “chronicity” with “a certain shapelessness in time,” adding that “chronic conditions seem to belie narrative altogether.” Marc Arthur, “Nostalgia and Chronicity: Two Temporalities in the Restaging of AIDS,” Theatre Journal 73.1 (2021), 19-36 (24-25); Elizabeth Freeman, “Hopeless Cases: Queer Chronicities and Gertrude Stein’s ‘Melanctha,’” Journal of Homosexuality 63.3 (2016): 329-438 (336). ↩

- See a recent special issue on “New Work in Transgender Art and Visual Culture Studies,” especially the editors’ introduction: Cyle Metzger and Kirstin Ringelberg, “Prismatic Views: A Look at the Growing Field of Transgender Art and Visual Culture Studies,” Journal of Visual Culture 19.2 (2020): 159-170. ↩

- C. Riley Snorton and Jin Haritaworn, “Trans Necropolitics: A Transnational Reflection on Violence, Death, and the Trans of Color Afterlife,” in Transgender Studies Reader 2, eds. Susan Stryker and Aren Z. Aizura (New York: Routledge, 2013), 66-76 (66). ↩

- Patrick Staff, “A Structural Idea of Fluidity: Gil Leung and Patrick Staff,” Mousse 45 (2014): 280-283 (281). ↩

- Sigmund Freud, “Mourning and Melancholia,” in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Vol. XIV (1914-1916), trans. James Strachey (London: The Hogarth Press), 243-258 (245); Douglas Crimp, “Mourning and Militancy,” October 51 (Winter 1989), 3-18 (6). ↩

- Crimp, “Mourning and Militancy,”4. ↩

- Many of the examples Crimp cites propagate self-accusational myths of morality: “we lie, deny reality, have no standards; we are narcissistic, self-indulgent, self-destructive, unable to love or even form lasting friendships; we flaunt it in public, abuse alcohol and drugs; and our community leaders and intellectuals are fascists.” Crimp, “Mourning and Militancy,” 13. ↩

- In a later essay entitled “Melancholia and Moralism,” Crimp sets his sights on American media’s “regimes of the normal.” And while this critique of an insistent moralism and normativity assists recognizing the dangers of writing reductive blame, my attention remains with his earlier essay’s more explicit psychoanalytic (re)interpretation of mourning and melancholia. Crimp, “Melancholia and Moralism,” in Loss: The Politics of Mourning, eds. David L. Eng and David Kazanjian (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2003), 188-202 (201). ↩

- Freud, “Mourning and Melancholia,” 246. ↩

- Crimp, “Mourning and Militancy,” 14. ↩

- Crimp, “Mourning and Militancy,” 16. ↩

- David L. Eng and David Kazanjian, “Introduction: Mourning Remains,” in Loss: The Politics of Mourning (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2003), 1-28 (2). ↩

- Eng and Kazanjian, “Introduction,” 2. ↩

- Eugenie Brinkema, The Forms of the Affects (Durham and London: Duke University Press), 70. ↩

- “Mourning,” writes Freud, “is regularly the reaction to the loss of a loved person, or to the loss of some abstraction which has taken the place of one, such as one’s country (Vaterland), liberty, an ideal, and so on.” Freud, “Mourning and Melancholia,” 244. ↩

- Crimp, “Mourning and Militancy,” 11. ↩

- Crimp, “Mourning and Militancy,” 10. ↩

- Jack Halberstam stresses the variability of queer experience in A Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives (New York: New York University Press), 2005. ↩

- Patrick Staff, Interviewed by Katie Guggenheim, February 2015, London. In Patrick Staff: The Foundation, ed. Aileen Burns and Johan Lundh (Milan: Mousse Publishing, 2015), 114-121. ↩

- “And the history of museology,” writes Crimp, “is a history of all the various attempts to deny the heterogeneity of the museum, to reduce it to a homogenous system or series.” Douglas Crimp, “On the Museum’s Ruins,” October 13 (1980): 41-57 (50). ↩

- Andy Campbell, “How to Talk About Tom,” in Bound Together: Leather, Sex, Archives, and Contemporary Art (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2020), 55-79. ↩

- Campbell, “How to Talk About Tom,” 62. ↩

- Campbell, “How to Talk About Tom,” 75. ↩

- Carolyn Dinshaw, Getting Medieval: Sexualities and Communities: Pre- and Postmodern (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1999), 1. ↩

- See Dean Spade, Normal Life: Administrative Violence, Critical Trans Politics, and the Limits of the Law (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2015). ↩

- Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1: An Introduction, trans. Robert Hurley (New York: Vintage Books, 1990), 43. ↩

- Pavle Levi, Cinema by Other Means (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 42. ↩

- Elizabeth Freeman, Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2010). ↩

- Mathias Danbolt, “Disruptive Anachronisms: Feeling Historical with N.O. Body,” in Temporal Drag, eds. Pauline Boudry and Renate Lorenz (Ostfildern, Germany: Hatje Cantz, 2011), 1982-1989 (1986). ↩

- Nancy Ordover, American Eugenics: Race, Queer Anatomy, and the Science of Nationalism (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003), 123. ↩

- Tavia Nyong’o, The Amalgamation Waltz: Race, Performance, and the Ruses of Memory (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2009), 136. ↩

- Crimp, “Mourning and Militancy,” 17. ↩

- Lee Edelman, Carolyn Dinshaw, Roderick A. Ferguson, Carla Freccero, Elizabeth Freeman, Judith Halberstam, Annamarie Jagose, Christopher Nealson, Nguyen Tan Hoang, “Theorizing Queer Temporalities: A Roundtable Discussion,” GLQ 13.2-3 (2006), 177-195 (195). ↩

- Queer Futurity (New York: New York University Press, 2009). ↩

- “With the second property of the signifier, that of combining according to the laws of a closed order, is affirmed by the necessity of the topological substratum of which the term I ordinarily use, namely, the signifying chain, gives an approximate idea: rings of a necklace that is a ring in another necklace made of rings.” Jacques Lacan, Écrits: A Selection, trans. Alan Sheridan (London and New York: Routledge), 116. ↩

- Dick Hebdige, Subculture: The Meaning of Style (London and New York: Routledge, 1979), 44. ↩

- The term insinuates the active participation among the performers on-stage of the lessons of the drama. Bertolt Brecht, Große kommentierte Berliner und Frankfurther Ausgabe, ed. Werner Hecht et al., xxii.2, (Frankfurt/Main and Berlin: Suhrkamp and Aufbau, 1988-2000), 939-944 (941). ↩

- Nayland Blake, “Tom of Finland: An Appreciation,” in Out in Culture: Gay, Lesbian and Queer Essays on Popular Culture, eds. Corey K. Creekmur and Alexander Doty (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1995), 349-350. ↩

- Catherine Spencer, “The Pedagogies of Performative Afterlife,” Parallax 24.1 (2018): 19-44. ↩

- Freud, “Mourning and Melancholia,” 253. ↩

- “The manic subject plainly demonstrates his liberation from the object which was the cause of his suffering, by seeking like a ravenously hungry man for new object-cathexes.” Freud, “Mourning and Melancholia,” 255. ↩

- Freud, “Mourning and Melancholia,” 254. ↩

- Walter Benjamin, The Origin of the German Tragedy Drama, trans. John Osborne (London and New York: Verso, 1998), 93 and 95. ↩

- Judith Butler, “Afterword: After Loss, What Then?” in Loss: The Politics of Mourning, eds. David L. Eng and David Kazanjian (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2003), 467-473 (469). ↩

- Butler, “After Loss, What Then?,” 472. ↩

- Nyong’o, The Amalgamation Waltz, 164-165. ↩

- Nyong’o, The Amalgamation Waltz, 165. ↩