I can’t speak for all academics, but personally I have a comforting little secret to air: despite the composed, jet-set, fellowship-laden, idea- and ambition-saturated veneer I might strive so desperately to affect for professional presentation, I often don’t know what I’m doing. This is especially true at the beginning of a major project, where I mostly don’t know what I’m doing. On darker days, it’s easy to get down on myself. On brighter days, I manage to remember that bringing genuinely interesting, well-developed new knowledge into the world is incredibly hard work—even for the pros.

In the summer of 2012, following my second year of graduate school, I received a research grant from my alma mater, Oberlin College, to spend two months in Philadelphia laying groundwork for a dissertation prospectus. I had long been inspired by the exhibits and events hosted by the Visual Culture Program at the Library Company of Philadelphia, and the staff there in prints and photographs kindly let me take up residence in their study room for most of July and August. I had been handed keys to a kingdom but possessed little more than a foggy notion of what I was doing there. Assistant Curator Erika Piola listened with patience as I floundered through something resembling a research query. I was interested in early photography but not the photographs themselves. Rather, I was fascinated by photographs that had been translated into prints. Did they have prints based on photographs? What about examples of printers and photographers collaborating in the 1840s and 50s? I couldn’t articulate what I wanted to find or why I even sought it in the first place. In short, I was working less from concrete, accrued knowledge and expertise than from itches, conjectures, hunches and feelings. Naïveté provoked constant wonder and worry. How would I know when I found something good and useful—something worth pursuing? Would I even know what to do with it when I did? I confess, I felt like an absolute idiot.

At one point, Erika suggested looking through their collection of lithographic portrait prints by Philadelphia artist, Albert Newsam (1809-1864). A deaf, mute orphan, whose arrival in Philadelphia at age ten coincided with the establishment of the country’s first schools for the deaf, Newsam’s life took a fortuitous turn that a generation earlier would likely have been unavailable to him. Educated at the new Pennsylvania Institution for the Deaf and Dumb as a ward of the state, he began apprenticing as a teenager with Cephas Childs—an engraver who was busily studying the new planographic printing process from Europe known as lithography. Bypassing the need for the intermediary step of engraving, the lithographic medium was incredibly well suited to draughtsmen, as it enabled them to streamline, multiply and monetize their talents in copying and sketching. The gifted Newsam thrived in this emerging industry and image ecology, gaining renown for his pictures. He remained with the printing firm for several decades (and through various ownership changes) until a stroke forced him to retire in the mid-1850s.

I became utterly entranced with Newsam’s fascinating (and ultimately tragic) story, but didn’t know what to make of it. Filed away in a kind of idea incubator in the back of my mind, it has taken more time, more reading and more thinking for me to begin figuring that out. I had started, really, with just a “pebble in my shoe,” as one advisor once put it: a suspicion that the history of photography’s love affair with its own origin story had somehow managed to elide entire sectors of visual culture production that preceded and co-existed alongside it. Newsam has since emerged as one of the interrelated studies I am now embarking upon to expand this given history.

While this particular odyssey feels unique to me, I suspect its general arc is quite familiar to most scholars and researchers. It is also the kind of messy, formative process of discovery that often gets written out of our final products—lingering (if we’re lucky) in talks, interviews or dinner-party conversation. The mark of insightful, effective academic writing is, after all, hiding our work. Like an elegantly plated meal in a upscale restaurant, not a trace of the fumbling mess and chaos of the kitchen should arrive at the diner’s table. Yet ironically, this table is where apprentice humanities scholars sit for our training. For the most part, we read the polished and published work of those ahead of us, while struggling to wrangle the mess in our kitchens. Writing groups and workshops go a long way toward bridging this pedagogical gap, but even these cannot address the less-choate phases of wandering and wondering that characterize the research process.

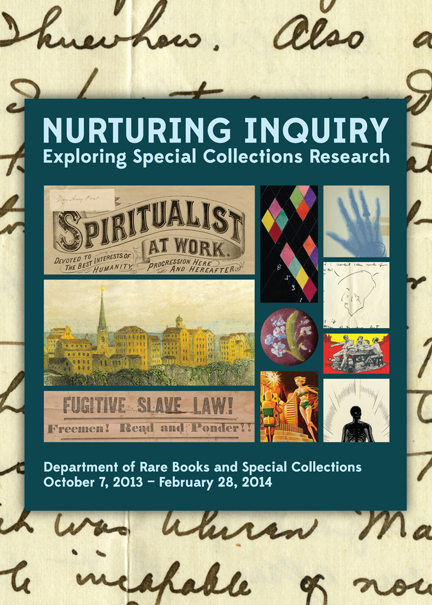

Seeking to bring the kitchen to the table, I proposed and helped develop a new exhibition now on view at the University of Rochester Library’s Department of Rare Books and Special Collections called Nurturing Inquiry: Exploring Special Collections Research. Co-curated with staff archivists and preservationists Phyllis Andrews, Lori Birrell and Andrea Reithmayr, the show offers a self-reflexive look at the collections through a lens of research-in-action. Each curator worked with researchers who have labored here—sometimes arriving on site in the same condition I narrated above—to produce essays of original scholarship ranging from the undergraduate term paper through the dissertation chapter and all the way up to the published monograph. The exhibition displays these endeavors alongside a sampling of primary sources used and, most importantly, personal statements reflecting on the researchers’ own experiences and processes. By offering a glimpse into what our work normally seeks to hide, my hope is that Nurturing Inquiry can help to both demystify this particular form of intellectual labor and increase camaraderie between its practitioners—at all points of our scholarly forays and careers.

Clockwise from Left: Introductory panels flanked by enlarged manuscripts that invite viewers into the primary task of transcription, participating researcher work on nineteenth-century spiritualism in the Rochester area, and participating researcher work on literary and photographic promotions during WWII.

Nurturing Inquiry: Exploring Special Collections Research is on view until February 28, 2014 in the Rare Books and Special Collections Department, Rush Rhees Library (2nd Floor), Monday through Friday from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Saturdays from 11 a.m to 3 p.m.

Please join us in the gallery for an opening celebration, featuring refreshments and lightning talks by research contributors on Tuesday, November 12, 2013 at 5 pm.