Ullens Center for Contemporary Art’s (UCCA) summer group exhibition Society Guidance (Part I) is a show lesser seen. Compared to the institution’s other summer exhibition, the spectacularly displayed Picasso: Birth of a Genius, coterminously happening onsite, this well-researched curatorial project about Chinese art and culture in the 1990s gained much less viewing and media attention. A not-so-trivial detail is telling of the two shows’ relation: in order to see Society Guidance, I had to purchase the 150 RMB (22 USD) ticket and first view the birth of Picasso. Such a comparison may seem provincial at first: for one, Picasso is a great modernist whose first major retrospective in China is fitting for a contemporary art institution like UCCA. As its Director Philip Tinari was quoted saying, “For UCCA this marks the realization of a dream we have held since our opening in 2007, to present not only recent developments in contemporary art but to examine the underpinnings of the contemporary by showing modern masters.”[1] But perhaps more importantly, a show like Picasso grows out of the complex interplay of several cultural institutions of which UCCA is only one (though admittedly a major one). Supported by the Musée National Picasso-Paris and curated by its Head of Collections, Emilia Philippot, Picasso is the direct result of Sino-French cultural exchange, manifested “at the highest levels.”[2] The show constitutes an important part of the 14th annual Festival Croisements, an art festival organized by the French Embassy in China. We can perhaps infer that, for pragmatic reasons, Picasso reflects more of the bilateral cultural dialogue on such “highest levels” than any individual curator’s understanding of how to tell the life story of a Western modernist in China. Still, the here and now matters. Why in 2019, in Beijing, does the execution of a show like Picasso still take on the framework of “an artistic Genius?”

Thus, to frame Society Guidance in relation to “the West” and to Western modernism—in part, by this show’s proximity to Picasso—is a somewhat paradoxical act. The show is not at all burdened by Western questions—such as “how do these works relate to the historical avant-garde or to the neo-avant-garde?”—as they are often theorized in the West. While these questions are formed by the (necessary and timely) global turn of art history and its related attempts to imagine other forms of modernism, the urge to answer them is a burden for me, the art historian of contemporary Chinese art. But it is not primarily because of my art historical training that I see Society Guidance in relation to Picasso. It is simply part of the itinerary. The Picasso exhibition begins with a literal lineup—a commemorative and choreographed walk through a chronology of Picasso’s life—before one is allowed to enter the main gallery space, where the majority of works are displayed. But if one turns sideways along this walk, and wanders off the main route, one encounters two smaller gallery spaces: one to the left and the other to the right. There exists an entirely different lifeworld, and this is many visitors’ initial encounter with Society Guidance.[3] In order for me to meet the cultural scene of the Chinese 1990s, with its complicated and uneven cultural imaginaries of modernity and modernism projected onto a socialist reality, I have to first encounter the unambiguous shape of Western modernism.

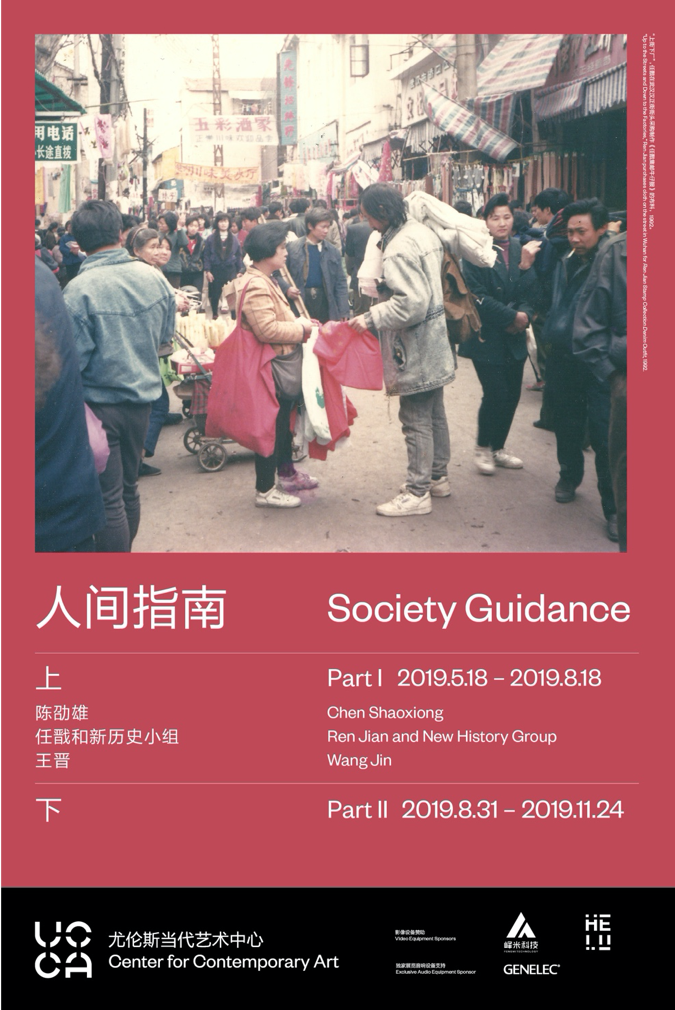

The title Society Guidance (人间指南) is drawn from the lo-fi fictional magazine at the center of a well-known 1991 Chinese television series Stories From the Editorial Board (编辑部的故事). As one of the most popular comedies of the decade, the show humorously introduces social problems that emerged during the changing economic and cultural paradigms of the 1990s with six distinctively characterized editors representing, roughly, three generations of Chinese intellectuals. The English translation “society guidance” attains a level of certitude and didacticism that is lacking in the Chinese phrase “Ren Jian Zhi Nan.” As a guide, society guidance is closer to a recording of the trials and errors of the human realm and is, to borrow the words of literary and cultural historian Tang Xiaobing, “in the spirit of pragmatic experimentalism.”[4]

Such a spirit is true for the current exhibition, which is best described as a re-staging of the diverse and multi-layered cultural scene of the Chinese 1990s. The relevance of this past scene is embedded in the contemporary world of China today, with a firm grasp of the historicity of its various forms of visual practices and pleasures. The show’s introductory text alludes to this awareness concretely when it asks: “What compels us to think the present situation with a past moment? Artists and researchers today, both young and old, must consider how to better coexist with the world. When art and culture no longer operate at the spiritual vanguard of the era, is it possible for us to work alongside the public to build another kind of culture?”

Culture here is capaciously defined. We see work that responds to the urban landscape of Guangzhou, to the newly formed art institution of biennales, to ideological symbols ranging from the U.S. dollar bill to the new CCTV tower, to denim designs and Chinese rock music. Featuring work by Chen Shaoxiong (1962-2016, Guangdong province), Ren Jian (b. 1955, Liaoning province), the New History Group, and Wang Jin (b.1962, Shanxi province), this exhibition considers what happens when these analytically astute practices are placed alongside other sorts of images—representations that collectively inform our understanding and imagination of Chinese “culture” in the1990s.

The first work we encounter in the exhibition space is Chen Shaoxiong’s two channel installation Sight Adjustor—7 (1998). In a dark room constructed at the entrance of the exhibition, two channels of videos are projected onto opposing sides of walls. Both projectors installed on the ceiling rotate in a clockwise motion and therefore cause the two video channels to move accordingly alongside the walls of the dark room. Activated viewers of Sight Adjustor are thus caught in-between the competing actions of seeing and turning, with no definitive relationship established between the viewing eye and the moving images. To make things more disorienting, the camera in both videos pan in a similar motion from left to right, presenting footages that oscillate between those of Guangzhou’s crowded urban environments—shopping centers, farmers markets, a bowling venue, a living room space—and closeup frontal shots of individual urban youth. “Adjustment” becomes the most accurate descriptor of this embodied experience of sight/site, a general but also capacious response to the rapidly changing landscape of Gaungzhou in the 1990s.

Sight, or what the artist himself calls “methods of seeing,” is the theme of three other exhibited works by Chen Shaoxiong. Street—2 (1998) and Street—Tianhe Plaza (1999) are from a series of photographs that Chen took in front of busy commercial streets in Guangzhou, with his hands holding a cardboard model of the street view in the foreground. These cardboard models are what the artist calls “scenery monuments.” They are crystallizations of Chen’s previous viewing experiences, on a specific day at a specific time, memorialized as papier collé and then placed back, in this current series of photographs, onto the ever-shifting urban world from where the views first came. These re-staged photographs thus index two layers of reality, one processed by the artist’s experience, the sedimentation of past moments, and the other bracketed by the automated mechanism of the camera. But is what we see a result of our past experience purely? Or is it a result of a learned concept, a manifestation of our social positioning, of what we dreamed last night or saw on television just now? These questions regarding what makes and unmakes a viewing subject, and what goes into the subject’s perception of reality are at the center of Chen Shaoxiong’s work presented in the exhibition. If Sight Adjustor—7 and the Street photographs sought to tackle these questions within the realm of the purely visual (and the visceral), then the 1997 video Landscape—1 functions like a theoretical guide to Chen’s visual manifestations. Here we see the artist working like an analytical philosopher, posing questions one after another about landscape, image, language, seeing and reality to his circle of art-world friends. One of these interviewees is artist Chen Tong’s toddler son Chen Huanle (陈欢乐). Huanle’s single consistent answer to Chen Shaoxiong’s continuous exposition about landscape is that “a great landscape is a landscape with more McDonald’s.”

Although China’s reform and opening to a market economy began as early as 1978, the real intensification of consumer culture and wealth did not become a felt environment until the 1990s. In 1992, Wang Jin, a recent graduate from Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts, returned to his home city Beijing and found a set of discarded bricks from the Forbidden City’s renovation project. He painted images of U.S. dollars onto these old wall bricks and titled his work “Knocking on the Door.” In Society Guidance, this series of work made between 1992-1995 is presented anew as enlarged C-Print photographs with an added subtitle Knocking on the Door—Presidents on U.S. Dollars (1992-1995). Each painted brick is placed on top of an old box with a label that reads: “67 wooden-handled grenade, 78-72-622, set of 30 with a total weight of 23 kg.” The tint of the photographs alternates between a night-vision-goggle-green and a subdued sepia. In Chinese colloquial terms, bricks that one uses to knock on the door are stepping stones to success. They are, in other words, instruments. The symbolic value of the U.S. dollar as China’s brick that knocks open the door of the global capitalist system cannot be more apparent. But Wang Jin’s choice to present Knocking on the Door on pedestals of grenade cases also makes apparent another layer of fact about the instrument at hand: the U.S. dollar is not only a financial instrument, it is a lethal weapon, a mighty military regime. With such a brick in hand, are we prepared for its wealth, as well as its violence?

A separate room of Society Guidance, constructed as a reading room, centers on the work of Ren Jian and the New History Group. This curatorial decision is based on the fact that two major actions undertaken by the New History Group, Disinfection in 1992 and 1993 Mass Consumption, exist now only as archival files. Rather than putting together photographic or filmic recordings —those traditionally privileged parts of the “work” on display—Society Guidance contextualizes these archival files in relation to other textual publications and criticisms that together informed the practices of the New History Group. Disinfection (1992) can be understood as a kind of “institutional critique,” responding directly to the first Guangzhou Biennale in 1992. Artists involved in the New History Group were interested in the emergence of a new institution of art established in relation not only to the older state-endowed socialist art institution, but also to the opening of an art market and to the increasing importance of curators, critics, and their individual roles in the art world. The action of 1993 Mass Consumption is representative of the groups’ conception of “art as material product.” This conception of artwork as consumer products came out of the group’s hope to meld art into life. The detailed archival documents on site are crucial to a situated, historical understanding of 1993 Mass Consumption, which, bracketed from its formational context, can be easily aligned in “form” with many other art practices in the West. The concern here is not simply to transform artistic practice into commodity production, so that consumption becomes the Chinese art-goer’s liberated form of artistic reception. Rather, the concern of the New History Group’s institutional critique is embedded in the artists’ historical understanding of their own present— a time when the institution of art was radically reconfigured—forced open by new possibilities and new channels of circulation. The New History Group was not at all interested in individual artistic freedom or the claim “art for art’s sake” that emerged briefly in the history of contemporary Chinese art. The group wrote in the voice of a manifesto in 1993 that:

In brief, the product art, which goes back to life itself, completely deconstructs the appreciation of the beautiful free of utility and the view of “art for art”. It does not subsist with hardship in museum but goes into factory, shop, restaurant, station and ordinary home. It is like clothes which can be put on and off, like letters which can be delivered, like photographs which can be copied, like food which can be tasted. Thus from 1993, the product art will go to all over the country, all over the world.

This vision of product art driven by a desire for mass dissemination and social engagement echoes more deeply with a socialist moment of artistic practice than one of liberal-capitalism. Its egalitarian wishes may be utopian, conditioned by a certain reform-era naiveté, but its political imagination is by no means confined, limited to the much-repeated tales of political dissidence. For this reason—and similar to the equally committed but pragmatic experiments of Chen Shaoxiong and Wang Jin—the New History Reading room presents its audience with a guide that lays out the complexity and multivalence of 1990s Chinese culture.

Society Guidance is an effortfully curated show. It presents us with a situated historical lens, a full set of analytical tools, and contextual framing and artistic sounding boards. The rest of the effort to understand our reality is on us; and there is no genius needed.

Society Guidance (I) was on view at Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, Beijing from 2019.5.18 to 2019.8.18

[1] http://ucca.org.cn/en/exhibition/picasso-birth-of-a-genius/

[2] http://ucca.org.cn/en/exhibition/picasso-birth-of-a-genius/

[3] During the three times I came to see Society Guidance, many of its visitors first encounter the show while being lost, as they wandered off the correct routes designed for Picasso: Birth of A Genius. There is a separate entrance for Society Guidance, though in this case the viewer has to walk pass the lines waiting to go through Picasso’s chronology and enter at a side opening.

[4] A spirit of “pragmatic experimentalism” is Tang Xiaobing’s phrase to describe the complicated socio-economic as well as cultural condition of contemporary China. See Visual Culture in Contemporary China (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 14.