Raysh Weiss

As the defining moment in the Biblical narrative of the Exodus from Egypt, the revelation at Sinai stands unparalleled in its political and theological importance in Israelite history. Curiously, the Pentateuch (or Torah) offers conflicting accounts of the revelation in two of its books, Exodus and Deuteronomy. Both accounts cryptically describe the physical qualities of the awe-filled moment. The difference between these descriptions raises important questions regarding the sequence of events at the revelation, its mode of address, and the nature of the sounds. Furthermore, each of the Biblical accounts describes the Sinaitic revelation from a different perspective, making a singular, cohesive representation of this event impossible. Illuminated Haggadot, dating as far back as the middle ages, prominently feature depictions of this defining event.1 A compilation of Biblical and Rabbinic texts, ritual prescriptions, and various blessings that serves as the manual for the Passover Seder conducted in Jewish homes, the actual text of the Haggadah dates from before the middle ages.

Here, I examine pictorial representations of the revelation at Sinai in six Haggadot: one from fourteenth century Spain and five from eighteenth century northern Europe. I will consider how the illustrations in these Haggadot depict the theophany at Sinai by drawing on motifs and aesthetic strategies from their own historical visual cultures. In each example, the Haggadah depictions of the revelation at Sinai evoke the synaesthetic experience of witnessing the revelation without necessarily allowing viewers to duplicate the Israelites’ trans-sensorial perception. In order to better understand the complexity of these elements, a brief cultural-historical survey of the Haggadah will elucidate the symbolic and contextual significance of these books and their images. I will then turn to the texts upon which these images are based and the interpretative challenges they pose.2 This brief analysis of the internal textual conflicts will help us appreciate the difficulties in creating any kind of unified image of this defining scene at Sinai when the Divine confronted the Children of Israel. Finally, a detailed formal analysis of each image will help determine how pictorial schema compensate for textual ambiguity and how much we can speak of an iconographic representation of the Sinai Theopany. Especially considering the famous Biblical injunction against “graven images,” the notion of graphically rendering a divinely abstract moment presents something of a challenge at the level of visual ‘translation.’ Moreover, the task of capturing in text the trans-sensorial experiences of the event, then translating those multiple perceptual (including sonic) experiences to pictures, prohibits any straightforward representation of the revelation.

General Context on the Haggadah: Seeing is Believing (and Remembering)

Second to Bibles, the most commonly illuminated object within the Jewish religion is the Haggadah. Serving a mostly pedagogical, ritual function, the Haggadah is a family-oriented, rabbinic text that often relies upon elaborate graphic visualizations to help recount the story of the Exodus from Egypt. The content, a mix of biblical and homiletical narratives, ritual instruction, and liturgy, began to be compiled in the second and third centuries (CE), with its core established in the ninth century in Babylonia. In addition to graphics adorning the edges of its pages, Haggadot, across the different regional traditions, tend to include some sort of exegetical marginalia as well. While the text of the Haggadah assumes primary importance at the Passover ritual meal, or Seder, the import of the artistic images adorning the pages is considerable. Both images and words assume a pedagogical role, encouraging Seder participants to relive the experiences of their ancient ancestors by becoming immersed—visually and aurally—in the account. In some ways, this sensory experience attempts to mirror the original experience of revelation, where both sound and image intertwined to create an overwhelming effect at the event’s commemoration.

First evidence of illuminated Haggadot dates back to the thirteenth century in Western Europe, where they were presumably created for private use.3 Today, about twenty Haggadot from the fourteenth century are known to survive. Scholars of European Jewish culture generally divide that world into three distinct geographic areas. These are Italy, Sepharad (comprised of the Iberian Peninsula, through Provence, down to the southern Mediterranean seaboard),4 and Ashkenaz (which included Germany and much of Eastern Europe). Beginning in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, each area produced illuminated Haggadot that reflected geographical particularities.5

As this study will reveal, however, expanding transnational communication via trade and migration and ever-developing means of producing and distributing Hebrew books helped break down such geographical classifications. By the eighteenth century we begin to witness intriguing hybrids in terms of style, aesthetic, and ritual. A critical development in the production and distribution of Haggadot came with, of course, the advent of printing in the fifteenth century. Around 1469, Hebrew printing surfaced in Rome and spread shortly thereafter to Amsterdam, Venice, Spain, Prague, and elsewhere.6 Mass production, rather than painstaking hand production and illumination, made the widespread availability and broad dissemination of Haggadot across the European continent a reality. Wide distribution, in turn, facilitated cultural cross-pollination that led to a blending of disparate regional styles.

The production of Jewish illuminated manuscripts, like that of general European illuminated manuscripts, flourished in the eighteenth century. In Europe, wealthy members of the Jewish elite who could commission manuscript copies of printed Haggadot fuelled the eighteenth century illuminated manuscript revival, particularly in Central Europe. In fact, many of the miniatures featured in the eighteenth century Haggadot were modeled on engravings in the 1695 and 1712 Amsterdam Haggadot. However, the most influential Jewish scribe-artists of this period were concentrated in Moravia.7 Whereas in the Middle Ages Jewish scribe-artists were, by and large, excluded from their non-Jewish (mostly Christian) counterparts’ artist guilds or scriptoria, certain Jewish European scribe-artists of the eighteenth century were now able to join book illustrators’ guilds.8 Because of this increased contact, Jewish Haggadah illuminations of this period began to reflect broader, more eclectic cultural motifs.

In one of the most famously confusing lines of the Bible, the Children of Israel are described as having “heard the lightning and seen the thunder” at the revelation at Mount Sinai.9 To understand Haggadah artists’ motivations then, is to consider this Biblical scene. As if the apparent confusion of the senses in this description is not sufficiently perplexing, the books of Exodus and Deuteronomy offer several distinct, and sometimes conflicting, accounts of the dramatic Sinai revelation. Certain accounts, such as those found in Exodus 19-20 as well as Deuteronomy 4-5, emphasize the sonic quality of the revelation. The accounts in Exodus 24 and Exodus 31, on the other hand, entirely omit the auditory element.10

The six Biblical passages containing descriptions of revelation’s sonic elements vary considerably in their treatment of the revelation’s sound, which, on the one hand, contains elements of mundane and actual sound, while on the other hand, contains within it the numinous element of the Qol, or “voice” of G-d Himself, or of his message. Perhaps the most striking image of sound is to be found in Exodus 19, the first account of the revelation, which portrays the “qol” as the sound of a great ram’s horn (Hebrew: qol shofar gadol) that—defying laws of physics—increases in intensity the longer it is sustained.11 This sound-image of the blaring horn recurs in Exodus 20:15, following the first iteration of the Ten Commandments: “And the people witnessed the thunder and heard the blare of the horn and the mountain smoking.”12 It is important to note here the specifically supernatural character of this sound described in the Exodus passages; sound here produces an effect (awe), not a message. Later, in Deuteronomy, this sound appears to be more intelligible.

In Deuteronomy 4:12, Moses reviews the story of the revelation, adding some fascinating detail. Describing the gift of the Ten Commandments, Moses says “The LORD spoke to you out of the fire; you heard the sound of words but perceived no shape—nothing but a voice.” In this passage, the qol assumes a slightly different tenor. Moses refers to a qol d’varim, or a “sound of words,” seeming to indicate that d’varim were among the sounds heard by the Israelites at the Sinaitic revelation. Likewise, the qol described in Deuteronomy 5:19—the subject of which is, again, the gift of the Ten Commandments— conveys the discernible speech of the divine: “The LORD spoke those words—those and no more—to your whole congregation at the mountain, with a mighty voice out of the fire and the dense clouds.” A literal reading of these texts suggests that the qol invoked in the Exodus accounts emphasizes a more sensational, visceral auditory encounter of ‘raw sound’ than the qol in the Deuteronomic account. The differences in these textual accounts culminate in a variety of visual renderings in depictions of this scene in the Haggadah. Whereas in certain Haggadot, the raw sound is underscored by color and composition, in other manuscripts, finely-printed words appear in the place of an ‘unimaginable’ Divine source, arguably to manifest the “intelligible sound.”

Another equivocation between various revelation accounts is the physical positioning of the people vis-à-vis the mountain and, consequently, their ability to hear across distance. Spatial perspective partly dictates aural perception. As mentioned above, the people are quoted as begging Moses to be excused from the mighty Divine voice because of its overpowering quality. While most revelation narratives suggest spatial distance between the Divine and the assembled multitude (Ex. 19:17, Ex. 19:24, Ex. 20:15 and 18, Ex. 24:2 and 9-18, Deut 4:11, and Deut. 5:5), some commentators understand the Israelites as quite literally standing “under the mountain.” One of the most famous post-Biblical accounts of the revelation at Sinai, the discussion in the Talmudic Tractate Shabbat, describes God as literally holding the mountain over the people’s heads.13 This account became deeply entrenched in the popular imagination of Jewish and neighboring peoples. In multiple suras of the Qu’ran, Mohammed vividly describes this very image of the revelation at Sinai.14 In these suras the Lord himself “persuades” Israel to accept the Law by holding a mountain over its collective head!

If the task of the exegete here proves challenging, then the work of the artist attempting to capture the “spirit” of this moment, centuries later and continents apart, is all the more daunting. Exegetes struggle to describe how Israelites heard the lightning at Sinai. How, then, do artists make sense of these seemingly inaccessible images and scriptural paradoxes? Much in the same way readers of the Bible actively grapple with the elusive quality of the divine and sonic elements suggested in these scenes, artists must concede to the inaccessibility of these descriptions and develop a set of signifying elements to visually compensate or the irreproducible sensation of the ineffable, infinite quality evoked by these cryptic descriptions.

How then do these complex layers of narrative translate into images? Do Jewish illuminated manuscripts establish iconic motifs, or do they create a standard depiction of the Sinai revelation? In order to answer these questions, let us turn our attention to pictorial renderings of the revelation at Sinai. This scene is most famously (and most commonly) featured on the pages of Passover Haggadot, which explicate the events surrounding the Biblical account of the Exodus from Egypt and the revelation at Mt. Sinai for Jewish liturgical and didactic purposes. The overwhelming bulk of Passover Haggadah compilations featuring images of the revelation at Sinai originated in Northern Germany in the eighteenth century. A close examination of the context and content of pictures of this scene from these six different compilations will help shed light on the ways in which this uniquely intriguing Biblical “moment of sound” was envisioned.

A Formal Analysis the Revelation at Sinai

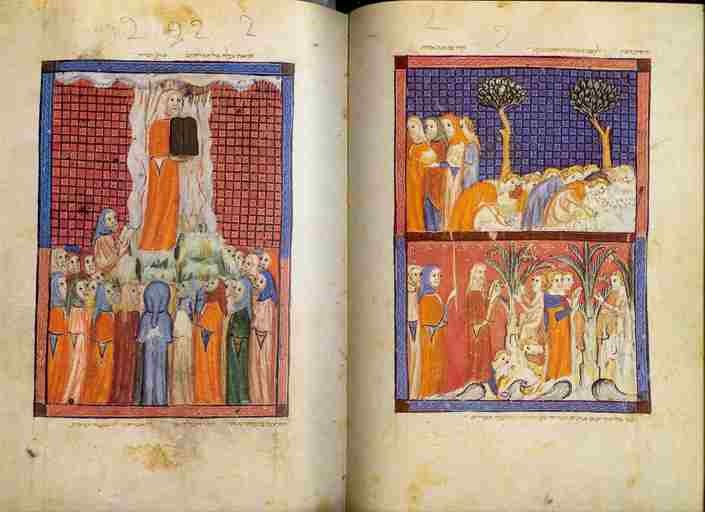

Until the eighteenth century, Haggadah illustrations—especially those produced in Western Christian lands—rarely included the Giving of the Law scene (the revelation at Mt. Sinai). However, the few notable exceptions that do exist help sharpen our understanding of the iconographic significance of themes and patterns that emerge later. Perhaps the most notable of these earlier representations of the Revelation at Sinai can be found in the bold image situated prominently on a full page toward the beginning of the Sarajevo Haggadah [Fig. 1].15

Figure 1. Unknown, “Revelation at Mount Sinai,” Sarajevo Haggadah, 14th century, painting on vellum, facsimile courtesy Spertus Institute of Jewish Studies, Chicago.

The Sarajevo Haggadah dates from mid-fourteenth-century Catalonia. Like other Haggadot originating from the Iberian Peninsula (part of the Sepharad region), the Sarajevo Haggadah includes a fully illuminated Biblical cycle at the beginning, depicting the creation of the world through the life and death of Moses. The revelation scene is included in this set of drawings on the left page. This cycle of miniatures closely resembles Latin Biblical illuminations of the same period. Upon the conclusion of the lavishly graphic Biblical cycle, the Haggadah text proper commences and pictorial illustration thereafter is sparse. Graphic embellishment is largely limited to the province of calligraphy.

In the Sinai scene, people stand at the mountain base and crowd the front of the picture. The background is not a desert scene, but features a pale crimson, rectilinear geometric design.16 The bodies’ scale defies the rules of perspective. Contrasting shades of clothing mute the pale mountain. In the Sarajevo images, the human figure trumps the specificity of place or environment.

The impossible scale of the figures stridently dwarfs what little we see of Mt. Sinai. Scale in this case should not be understood literally, but rather as a perceptual guiding mechanism. The way the artist reserves a full page for the Revelation scene (whereas most all other images included in the Sarajevo Haggadah Biblical Cycle are divided horizontally, with one scene placed atop the next), supports this understanding of scale. Occupying its own page formalizes the disorientation of “hearing the sounds” as it helps viewers recognize the singularity of this moment.

This depiction of Sinai in the Sarajevo Haggadah seems most in line with the descriptions in Exodus 19, which includes imagery of thundering, lightening, a thick cloud, and a horn of great sound. Not only does Moses, figured at left, stand amidst a blaze of flames, a shofar appears from the sky, signified by a continuous wavy white plume of clouds, above Moses’ head, to the right. Commenting on the especially tight composition and the distinct flatness of this image, Jewish art historian Joseph Guttmann explains that the pattern of featuring full-view figures in the foreground against a background of only heads—about twenty discernible faces in all—is often found in imperia Roman art.17 The figuration also contains hints of a French gothic influence, with elongated bodies casting their eyes upward. Despite the vertical emphasis of the human figures, the crowd itself is fused into a broad horizontal layer at the base. This geometric confusion—the refusal to flatten the event into a quickly discernible scene—mimics the resistance to comprehension achieved when Exodus describes the Israelites as seeing the sounds. The revelation scene in the Sarajevo Haggadah gives us visual noise.

The color palette remains relatively stable throughout the cycle, both within and immediately around the images. A red-blue border with white rinceaux adornment frames each scene while shades of royal vermilion, deep azure and crimson work together with costume to sugget each figure’s noble status. Notably, everyone represented in the scene at Sinai—Moses, the left side figure (presumably either Joshua or Aaron), as well as all others assembled—wear garments typically reserved for scholars or other great figures in the Jewish community of fourteenth-century Spain. Indeed, the figures don long, flowing cotes and garde-corps, with hoods drooping over the back.18 By presenting Biblical figures according to the contemporary sartorial standards of the day, these depictions reinforce and further amplify the gravitas of the revelation.

Above all, the Sarajevo Revelation scene foregrounds the Israelites (quite literally) and draws immediate visual attention to the tablets, depicted in the darkest color value of the image. Any hint of the Divine is stripped of such vibrant hues and represented in more irregular forms of the cloud, the mountain and the blazing flames. Because of the tightly packed composition, the shofar–the supposed source of the mighty sound–assumes an almost secondary and mundane visual status. The scene of revelation in the Sarajevo Haggadah thus emphasizes the earthly, visual elements of the revelation, while underplaying the more numinous aspects of Divine sound.

Nearly three hundred years after the production of the Sarajevo Haggadah, the scene at Sinai assumes entirely new contours in and around the Germanic lands, where distinct schools of scribe-artists in the Ashkenazi Jewish communities capitalized on expanded means of book distribution and production and began to codify Haggadah iconography.

With the advent of printing, Christian Europe witnessed a general decline in the production of illuminated manuscripts throughout the fifteenth century. And yet, thanks to the vitally central role scribe-artists played (and continue to play) in Jewish ritual life, Hebrew illuminated manuscripts never completely disappeared. It was not until the eighteenth century that Europe witnessed an illuminated manuscript revival.19 With the returning popularity of illuminated manuscripts in the rest of Europe, the production of illuminated Hebrew manuscripts also surged.

In addition to the importance placed on the ritual scribe a major catalyst of the eighteenth-century Hebrew illuminated book renaissance was the ascendance of a class of a noble class of Jews, or Hofjuden. With the Treaty of Westphalia and the close of the Thirty Years War, the status of Jews in Germanic lands began to change radically. The emergence of Hofjuden marked the rise of a Jewish wealthy elite who sought to beautify all aspects of Jewish life, including ritual items.20 Hofjuden would often specially commission Hebrew illuminated books. Since the artists commissioned were not necessarily Jewish, traces of Christian iconographical elements—particularly in Biblical scenes—are not uncommon.

Hebrew illuminated manuscripts underwent a series of fundamental changes as their content became exclusively liturgical in Western Christian lands during the eighteenth century. While the artists and scribes of eighteenth-century Hebrew illuminated manuscripts imitate copperplate engravings and printed lettering, they also infused their images with a humanist quality and a rococo spirit.[Roth, Jewish Art, 446.] Once again, issues of cultural and phenomenological translation assume primary importance: translation between registers of sensory experience, translation between event and narrative description, translation between narrative and pictorial representations, and translation across representation. This series of translations destabilizes the referent or that which is signified (in this case, the revelation at Sinai).

Essential to this study is a careful consideration of the iconographic elements and stylistic choices in the work of proselyte scribe-artist Abraham ben Jacob. Originally from the Rhineland area, Abraham ben Jacob completed his most significant work under the patronage of wealthy Jewish communities in the Netherlands. The Christian iconographical influence on Abraham ben Jacob’s work is especially heavy. Swiss artist Matthaeus Merian the Elder (1593-1650) is notable in this regard. 21 Although strongly influenced by Christian iconography, Abraham ben Jacob, following Jewish tradition, carefully avoids direct representation of God, thus modifying his style to suit his Jewish audience. Among Abraham ben Jacob’s most notable works is the Amsterdam Haggadah. First printed in 1695, this Haggadah was the first to use engraved copper plates (rather than customary woodcuts) for producing its illustrations, and was widely praised and imitated for its innovative techniques.

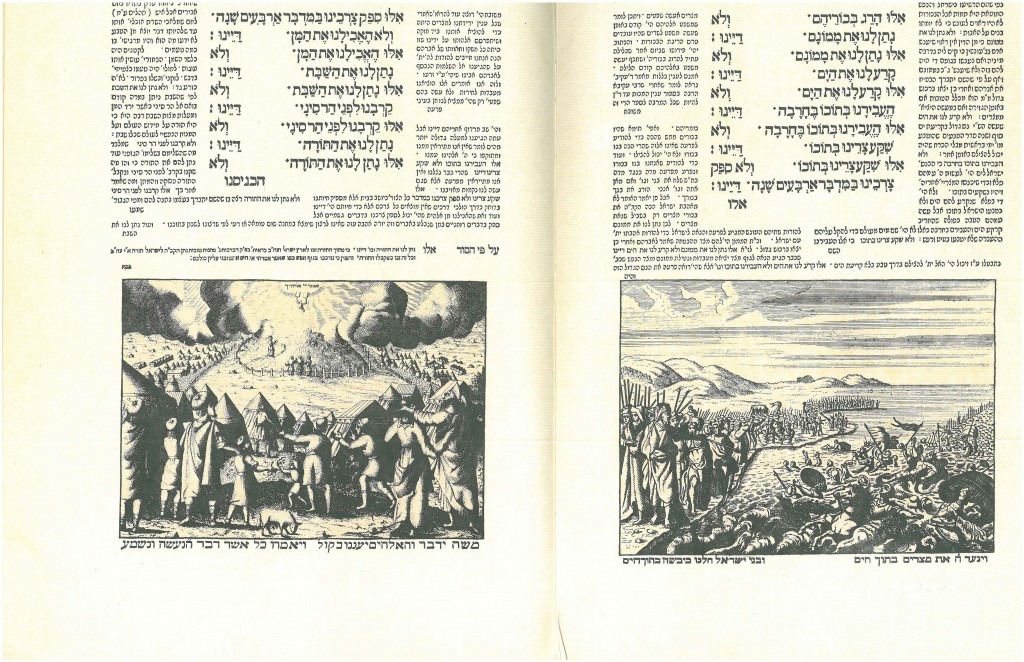

The creative and mechanical elements used to signify the Divine graphically stand out as among the most curious elements in the eighteenth-century illuminated Sinai images. In fact, the Amsterdam Haggadah’s revelation scene uses different representational schema than its other scenes [Fig. 2].22 Here, within the body of the Amsterdam Haggadah, the image is placed immediately below the text of the Dayenu song, which recounts the many great things God has done for Israel, including the giving of the Law at Mt. Sinai. In Abraham ben Jacob’s revelation scene, the wealth of graphic detail, conflicting vectors of visual attention, competing planes, and rhythmic sense of positive and negative space all amount to a rather daunting visual experience. To convey the absorbing sense of awe is to create a sense of distance between Moses and the Israelites receiving the law. A barely visible Moses stands in the center at the top of the page, marking the point at which the receding land and billowing smoke converge with the figures’ gazes. Under an overwhelmingly brilliant sun, he hoists the tablets.

Figure 2. Abraham ben Jacob (b. 17th century), “Revelation at Mt. Sinai,” Amsterdam Haggadah, 1695, copper engraving, British Library, facsimile courtesy of Spertus Institute of Jewish Studies, Chicago.

The iconographical import of the sun is key here: not only does it designate the epicenter of this Divine maelstrom, but it also contains text and radiates long thick rays in all directions.23 The rays point outward to literalize the transmission of the law. The text within the sun reads “Anokhi Hashem Elohekha” (I am the Lord your God), a phrase taken directly from the first of the Ten Commandments. In attempting to capture the vision-defying Divine force, Abraham ben Jacob resorts to text as a signifying measure. The artist emphasizes the heaviness of the clouds (again, closely following the description from the Bible) by using chiaroscuro to accent the three-dimensional, kinetic quality of the heavens. The winding multi-directionality of the clouds mirrors the negative space demarcating Moses and his attendants’ position near the mountain from the area populated by the rest of the children of Israel. The figures’ comportment in the foreground of the page further implies a sense of nearly chaotic shock, with each of their glances pointed in varying directions.

Both the Divine force and the sounds described in the Biblical sources defy and exceed visual representation. Amidst the impossible cacophony of divinely inspired sounds and images, the text alone becomes accessible to rational human comprehension. Abraham ben Jacob relies on the famous text as a reminder of that which we cannot possibly fathom or personally feel as readers, let alone remember. By inserting an easily identifiable passage the artist anchors the picture to a specific meaning while allowing the visual elements to suggest a synaesthetic dimension: spectators fix their sight on the light that emanates thunder and are led to contemplate that which is beyond normal human understanding.

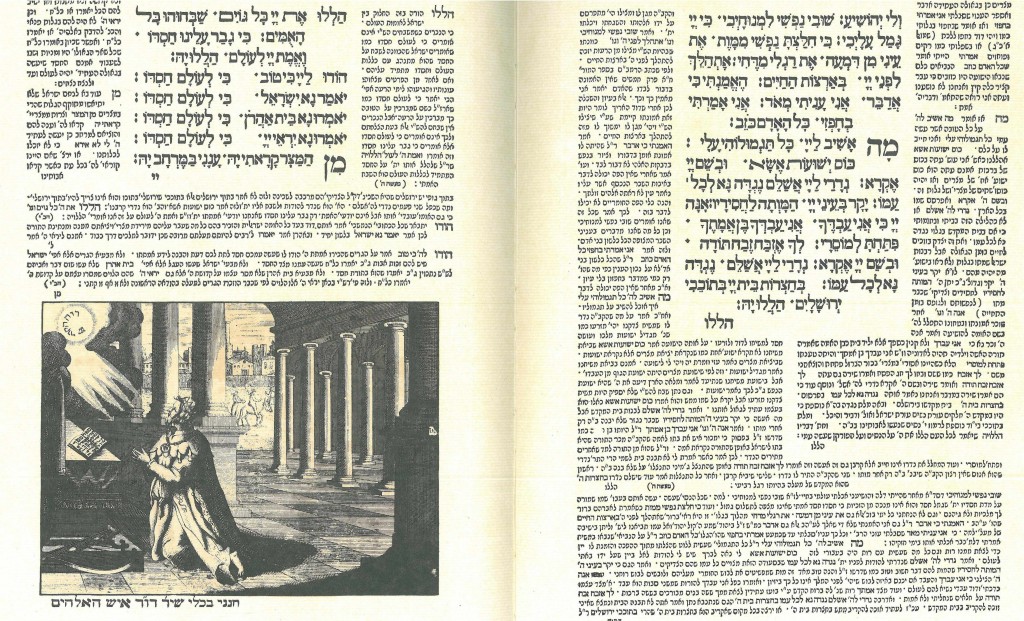

Later in the Amsterdam Haggadah, in a scene that illuminates the Hallel section of the Seder service, Abraham ben Jacob employs the same technique of pairing the sun with a brief text about the Divine [Fig. 3].24 In this engraving of King David, to whom the authorship of the Psalms contained in the Hallel is ascribed, is portrayed kneeling before the radiating sun image. Here, too, the sun embodies the Divine presence. Like the sun image in his revelation scene, ben Jacob’s sun contains text directly referring to God. Opposed to the direct, horizontal line of the three-word text at Sinai, the writing in the David scene outlines the sun. It reads, “Ruach ha’Kodesh” (the Holy Spirit). Other Haggadah illuminations of this region and period employ sun with text in similar ways.

Figure 3. Abraham ben Jacob (b. 17th century), David Kneeling Before God, Amsterdam Haggadah, 1695, copper engravings, facsimile courtesy of Spertus Institute of Jewish Studies, Chicago.

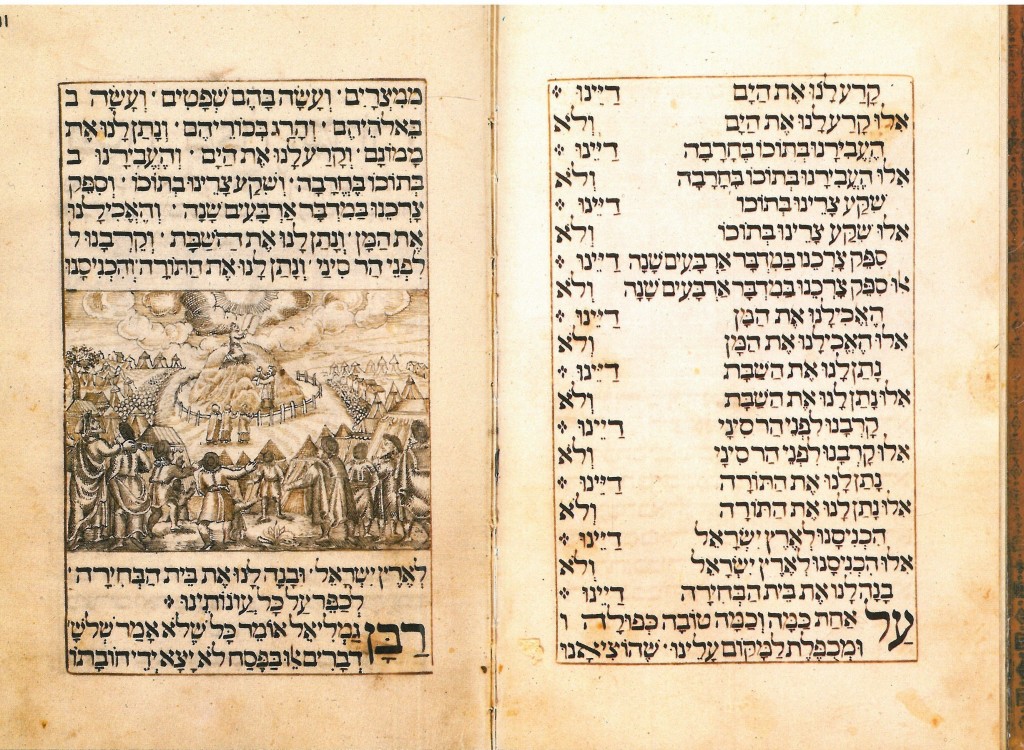

Lesser known than the Amsterdam Haggadah is the Moravian Haggadah from 1737. While the book lacks colophon or other hints of the artist’s identity, we do know that the Moravian Haggadah followed the format and style of the Amsterdam Haggadah.25 The Moravian Haggadah’s revelation scene is placed in the same part of the Haggadah service as the revelation scene in the Amsterdam Haggadah—beneath the song Dayenu—and draws upon the same basic layout as its predecessor. Nonetheless several notable differences between the two images of Sinai are immediately apparent [Fig. 4]. Differences in composition, tone, balance, as well as architectonic features all help create a more intelligible scene in the Moravian Haggadah.

Figure 4. Unknown, “Revelation at Mt. Sinai,”Moravian Haggadah, 1737, engraving, facsimile courtesy of Spertus Institute of Jewish Studies, Chicago.

More symmetrical than its Dutch predecessor, two registers of concentric forms organize the picture. Rings of tents fill the foreground. Upward-sweeping clouds dominate the top of the picture, echoing the structure of the camp below. Evoking sound through composition, the Moravian scene includes few non-instrumental figures in the foreground. Figures around the mount command viewers’ attention. The Moravian depiction enlarges the three figures we barely see in Abraham ben Jacob’s rendering, making them the fulcrum on which the symmetry pivots.26 In lieu of a shofar, internal text, caption, or other visual elements signifying invisible sonic sensation, the Moravian Haggadah Revelation scene relies on a rhythmic, circular structure to suggest sound.

A Moravian scribe-artist, Simmel of Polin, created another Haggadah Revelation scene at the beginning of the eighteenth century.27 Like Abraham ben Jacob and the anonymous creator of the Moravian Haggadah, Simmel of Polin placed his depiction of Sinai within the context of the Dayenu song. At first glance, the scene resembles the Amsterdam Haggadah’s version, with a unique cloud design, multiple vectors of activity, and empty space between people and mountain [Fig. 5]. But, unlike the two preceding examples, Moses is here pictured from the side, rather than frontally, holding up two connected tablets, unlike the separate ones featured in the Amsterdam and Moravian Haggadot.

Figure 5. Meshullan Simmel Sofer of Polna, Moravia, “Revelation at Mt. Sinai,” Heb. MS 8° 5573, 1718-19, Jewish National and University Library, Jerusalem, facsimile courtesy of Spertus Institute of Jewish Studies, Chicago.

Meshullam Simmel Sofer of Polna, Moravia

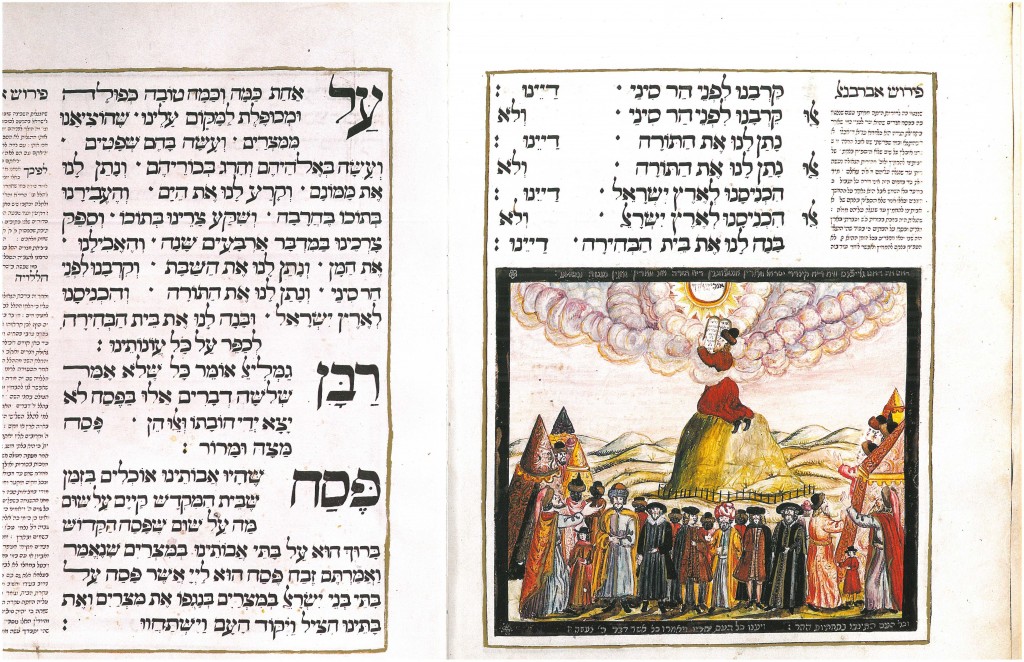

The Altona Haggadah (otherwise known as the Rosenthaliana Leipnik Haggadah) of 1738 is another of the Haggadot scripted “in Amsterdam lettering” [Fig. 6]. While scribe-artist Joseph ben David of Leipnik (originally from Moravia) followed the basic format and design scheme of the Amsterdam Haggadah, he was particularly innovative and skilled in his use of mixed gouache and water colors, achieving brilliant coloration in his rococo illustrations. He incorporated period-specific, distinctive genre-elements, especially apparent in the costume and architectonic elements.

Figure 6. Joseph ben David (b. 18th century), “Revelation at Mt. Sinai,” Altona Haggadah, 1738, parchment, British Library, facsimile courtesy of Spertus Institute of Jewish Studies, Chicago.

Joseph ben David’s rendering of the Giving of the Law represents the most radical departure thus far from the Amsterdam image. Instead of a flat, barren wasteland, mountainous terrain makes up Sinai. Smooth, open, monochrome white represents the sky. This atmospheric clearing directs viewers’ attention to Moses, the compositional rhythm of the clouds, and the curiously positioned people below. Perhaps the most perplexing feature of this particular version is the way in which Joseph ben David pictures the assembled multitude as largely facing away from the revelation. It is as if the crowd consciously poses for a group portrait.

The anachronistic dress also suggests that these people are actually elite northern European Jews of theeighteenth century. Likewise, the curiously angular tent design is particular to eighteenth-century architecture, both on the level of form and ornamentation. While it is certainly possible that these anachronistic elements are simply a matter of artistic license, it is also possible that portraying those receiving the Law at Sinai as contemporaries is a nod to the Rabbinic Jewish injunction that, in every generation, each Jew is obligated to see himself as if he himself had experienced the exodus from Egypt and the Revelation at Sinai. Thus, those who stand at the mountain in the Haggadah illustration, by resembling eighteenth-century European Jews, both visually imitate and thus symbolically embody their presence at this moment.

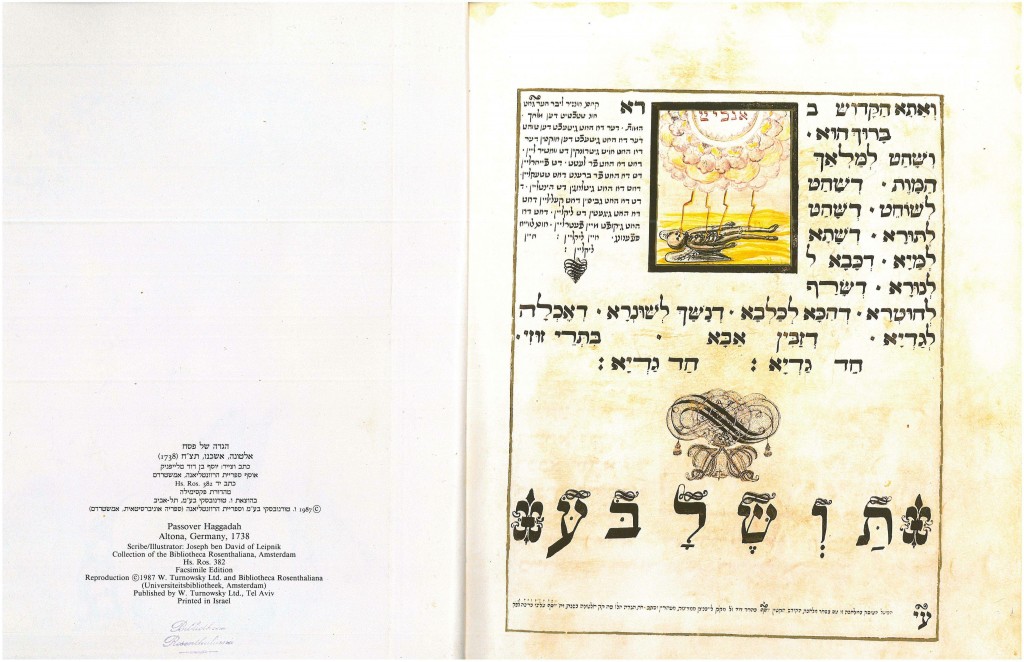

And yet, Joseph ben David retains several key signifying elements from the Amsterdam Haggadah. Both feature text emblazoned on a centrally positioned sun above Moses. We see this motif again towards the end of the Haggadah in Joseph ben David’s accompanying illustration of the Hagadya, a song chronicling a rather violent chain of animals devouring each other, culminating in God’s smiting of the Angel of Death. In Joseph ben David’s illustration, the final scene is almost comically depicted [Fig. 7]. Once again, we see the words “Anokhi Hashem” boldly positioned atop a sun from which rays emanate, destroying the Angel of Death. By reverting to text, Joseph ben David avoids direct representation of God as he magnifies the mystery of Divine presence.

Figure 7. Joseph ben David (b. 18th century), “Angel of Death (in Chad Gadya),” Altona Haggadah, 1738, parchment, British Library, facsimile courtesy of Spertus Institute of Jewish Studies, Chicago.

As with the Moravian Haggadah, the Altona Haggadah’s billowy smoke-like “clouds” suggest the sounds that emanated from heaven. Sound and God appear at once. Though linked in Revelation narratives and ben David’s picture, the forces of each Haggadah resist pictorial representation. Through repeated depiction in radiating circular forms, ben David flattens the synaesthetic experience of witnessing God into a picture.28 But the repeating rings also point to an ever-expanding affinity between God and sound.

Among the pictorial representations of the Theophany at Sinai, perhaps the most iconographically intriguing sample comes from the Copenhagen Haggadah of 1739, penned and illustrated by Uri Pheibush [Fig. 8].The Moravian scribe-artist lavished considerable attention on his historic and biblical representations, with an eye toward Biblical fidelity.29 Pheibush was among those artists to follow the general style of the Amsterdam Haggadah, but he often altered elements he found to be misrepresentative of the scenes themselves.30 Most Haggadah illuminators place the revelation scene on the page containing the Dayenu, where it serves as an illustration of the giving of the law, which is mentioned in one of the verses of this song. Pheibush places his scene, however, underneath the recitation of “Pesach, Matza v’Marror,” the three core components of the Passover feast according to the Haggadah text. This seemingly arbitrary placement is difficult to explain in light of Pheibush’s attentiveness to contextual detail.

Figure 8. Phillip Isaac Levy (b. 1720-1795), “Untitled,” Copenhagen Haggadah, 1739, parchment, Royal Library and the Jewish Community of Copenhagen, Denmark, facsimile courtesy of Spertus Institute of Jewish Studies, Chicago.

Despite the conservatism of his illuminations in terms of content, Pheibush makes important technical interventions. With a strong emphasis on painting with new techniques of coloring and composition, Pheibush also integrated local elements and contemporary details, such as furniture, home interiors, costume, landscape and heraldic elements. Despite the commitment to representational images and injection of contemporary elements, Pheibush’s images are surreal. They establish a warped sense of depth and are saturated in rich and contrasting hues.

Attempting to visualize Divine acoustics, the Copenhagen Haggadah Revelation scene culls multiple signifying elements from the depictions considered above.31In the Copenhagen depiction, the sun contains the text of the First Commandment, two shofars float mid-heaven and flank the sides of the mountain, and foreboding plumes of clouds submit the ethereal action to a familiar concentric structure. Circular clouds, here with shofars appearing suspended from their midst, again suggest the sound of God speaking. Foreground and background, the heavens and the earth, are demarcated here not only by spatial placement and scale, but also by color and saturation. The tents clustered at the base of the frame create an abrupt chromatic sweep of bold color, whereas the heavens revert to a more restrained and muted gray palette. The arrangement of tents marks another crucial difference between Pheibush’s depiction and earlier Haggadah paintings. No longer situated in a continuous, inclusive band, the tents are scattered in clusters.

The picture includes only two discernable figures in the distance, Moses and Aaron.32 Mirroring the pictorial absence of the Divine, the lack of people creates an eerie sense of anticipation. Indeed, the edges of the Copenhagen Revelation scene cannot neatly contain its contents, and every side and direction point outward, to a Beyond. Conceding to its representational inadequacy to depict transcendence (whether sonic, Divine, or both), this image seeks to exceed the frame in pointing to an ineffable and an invisible presence.33

The Revelation Scene and the Acoustical Sublime

In Moses and Monotheism, Freud famously remarked that the people of Israel’s conceptual/theological innovation of an inaccessible, invisible God “signified subordinating sense perception to an abstract idea, it was a triumph of spirituality over the sense.”34 Such an ostensibly anti-sensual legacy might seem to leave scant room for pictorial daring and virtuosity, and yet, upon reviewing the six depictions above, we see the immense outpouring of creativity such conceptual limitations inspire. The great sounds at Sinai, described by the Scriptures and imagined in the Haggadah pictures, all by virtue of their indeterminacy (i.e. their position outside the frame of the knowable in the narratives), manifest a feeling of the sublime in the Kantian sense: the failure of the human intelligence to comprehend the absolutely great.

The numinous, ineffable divine encounter that the Israelites experienced at Sinai emerges in the Biblical text via what Kant calls “subreption” (confusing the sensible with what belongs to understanding).35 Sound, which emanates from a space beyond the imagination of the narrative, comes to represent the unknowable itself, or, at the very least, becomes a vehicle for the transmission of some trace of that which lies beyond human comprehension. In a move away from the emerging rationalist norms of the time, the “acoustical sublime” of the Revelation text and its subsequent pictorial renderings gesture toward the failure of the Enlightenment project.

Despite the impressive stylistic diversity, variation of mood, and incorporation of local elements in each Haggadah’s different depiction of Sinai, one unifying element connects them all—the insertion of a recognizable present (through the integration of familiar images, such as landscapes, costume, and architectonic elements and motifs) into an eternity of wonder. Haggadah painters worked through familiar imagery, experimentation, artistic traditions, and religious conventions to depict the unknowable, the invisible or supravisible, and the extra-audible.36

- Plural of Haggadah. ↩

- In their thorough survey of Jewish book art, Ursula and Kurt Schubert advocate a close reading of the biblical and post-biblical rabbinic sources in interpreting the iconographical elements. See, for example, their discussion of the Giving of the Law. Kurt and Ursula Schubert, Jüdische Buchkunst, Vol. 1 (Vienna: Akademische Druck – ind Verlagsanstalt Graz, 1983), 91. ↩

- Joseph Gutmann, Die Darmstädter Pessach-Haggadah (Berlin: Propyläen, 1971). It should also here be noted that certain Jewish art historians, such as Chavivah Feld-Karmeli point to even earlier fragmentary evidence of Hebrew manuscript illumination–as early as tenth-century Yemen and Syria. See Ha-Metsayer Bi-Yetsi’at Mitsrayim. Jerusalem: Israel Museum, 1983. ↩

- In cultural terms, “Sepharad” refers to areas of the Jewish world where the predominant cultural/linguistic influence was rooted in the Spanish heritage of its Jewish population that originated in Spain and migrated to areas such as Bosnia, Turkey, Albania, and Macedonia. In these areas, the Spanish/Hebrew dialect Ladino was spoken by Jewish populations in other areas in Europe). ↩

- Raphael Loewe, The Rylands Haggadah: A Medieval Sephardi Masterpiece in Facsimile: An Illuminated Passover Compendium from Mid Fourteenth-Century Catalonia in the Collections of the John Rylands University Library of Manchester, with a Commentary and a Cycle of Poems (London: Thames and Hudson, 1988). ↩

- G. L. Schrijver, Seder Hagadah Shel Pesah: Altonah, Ashkenaz 498 (1738), Katav e-tsiyer Yosef Ben David Mi Laipnik (Tel Aviv: V. Turnowsky, 1987). ↩

- Chaya Benjamin, Copenhagen haggadah: Seder Hagadah Shel Pesah Ke-minhag Ashkenazim Ukhi-minhag Sefaradim Asher Lo Nir’eh Me-olam Ka-dimyon Ha-zeh ’em Perush Abravan’el U-pera, ‘a.p. Ha-sod Ve-tsiyurim Na ‘I’m…’ed Ma ‘ase Yadi…Uri Feyvush Ben Yitshak “Ayzek Segal (New York: Rizzoli, 1987). ↩

- Schrijver, “Introduction,” in Seder Hagadah. ↩

- Exod. 20:15, they “saw the voices.” Later in volume 19, it again says, “you have indeed seen me speak from the sky.” Perhaps this use of the apparently inappropriate verb “seeing” with regard to the perception of voices can be explained by the fact that seeing is a much more concrete and unmistakable–and, therefore, more memorable–sense than hearing. For example, it is quite easy to remember exactly how someone who has died looked, but it is virtually impossible to remember how they sounded. (See, for example, the Mechilta on Exod. 20:15-19). ↩

- Save the brief mention in 24:3 that the people answered in “qol echad,” “one voice,” and God’s direct summoning of Moses in 24:16, notably that there and in Exod. 31, the sense of the word qol, or voice, as something awesome or overpowering is conspicuously absent. ↩

- See Exod. 19:16,19. ↩

- NJPS translation, Exod. 20:15. ↩

- T. Shabbat 88a and also the account in Midrash in Avoda Zara 2b. ↩

- For a fuller discussion of this relationship, see Julian Obermann, “Koran and Agada: the Events at Mount Sinai,” The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures 58, no. 1 (1941): 23-48. ↩

- These pages read right to left; the image on the left is the Revelation at Sinai. The captions above the frame (translated): “Moses ascended to God/The Giving of the Torah,” the captions below the frame: “And they stood at the foot of the mountain; and the whole nation trembled/Everything that God speaks we will do and hear.” Today, this Haggadah is on permanent display at the National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina in Sarajevo. ↩

- This grid-like ornamentation is most likely inspired by the artistic tradition of the Mudéjar and the continuing legacy of Islamic art in Spain. It is also possible this is an aesthetic borrowed from contemporary French manuscript illumination, considering the close geographical and political relationship between Catalonia and France at this time. ↩

- Joseph Guttmann, Hebrew Manuscript Painting (New York: George Braziller, 1978). ↩

- Mendel and Thérèse Metzger, Jewish Life in the Middle Ages: Illuminated Hebrew Manuscripts of the Thirteenth to the Sixteenth Centuries (New York: Alpine Fine Arts Collection, 1982). ↩

- Laila Avrîn, Scribes, Script, and Books (Chicago: American Library Association, 2010), 135. ↩

- Cecil Roth, Jewish Art (Tel Aviv: Massadah, 1961), 443; and Schubert, Jüdische Buchkunst, 83. ↩

- Schrijver, see also Ha’Mitzayer b’yiziyat Mitzraiim, Haggadot Metzuyarot min ha’mayah ha’18, 20. Merian is well known for his Icones Biblicae (1625), and was, in turn, inspired by Han Holbein’s (1497-1543) famous biblical illustrations. ↩

- The Amsterdam Haggadah was printed in both 1695 and 1712. ↩

- The choice of placing the text in the sun is an intriguing one–perhaps because the creation of light was the first recorded consequence of Divine sound (namely, the utterance, “let there be light,”) as described at the very beginning of the Biblical account of the creation of the world. ↩

- The Hallel sections is a festival prayer of thanks, comprised of five Psalms. Each psalm expresses ecstatic praise of God. This section is famous for its musical imagery and the melodies it has inspired over the generations. ↩

- The Moravian Haggadah so proclaims this on the frontispiece, the commonly used formulation “In Amsterdam lettering.” ↩

- The three figures could be Aaron and two of his sons, the three patriarchs, or perhaps simply the elders described in the text. ↩

- Little is known about this 1718-19 Haggadah, see Heb. MS 80 5573 of the collection of the Four Quatre Haggadot. The artist is otherwise known as Meshullam Simmel Sofer of Polna, Moravia. ↩

- The important relationship between sound and circles for Pythagoras should also be noted here; later philosophers such as Al Ghazali also emphasize the divine quality of circular imagery. ↩

- Uri Pheibush was the son of Isaac Eisik Segal, also known as “Philip” Isaac Levy (1720-1795). ↩

- A classic example of this phenomenon is how in the scene of the Five Rabbis in Bnei Braq Pheibush emphasizes the five rabbis, whereas the Amsterdam Haggadah bases this scene on Merian’s portrayal of Joseph feasting with his brothers. ↩

- The Copenhagen Haggadah, like the Amsterdam Haggadah and so many others, uses the Divine-text-in-sun motif in its version of the David-kneeling-before-God scene. Here, even more than in the Amsterdam Haggadah (where at least there are awesome rays emanating from the sun with the divine inscription), the transcendent element is almost subdued to the point of neglect: the sun is timidly set behind imposing marble pillars and a drawn crimson curtain on the right. Also in terms of scale, the sun is dwarfed by the size and scale of the ambient elements of David’s palatial interiors. King David–called in rabbinic literature “the sweet singer of Israel”–is clearly shown here in his palace “workroom” with the tools of his work–the lyre and the pen and parchment with and upon which he wrote and sang the very poems of praise to God that are contained in the Hallel section of the Haggadah. And, even more significantly, the visual focus of this picture is toward the Sun (a visible manifestation of the invisible God), toward which David gazes worshipfully. ↩

- The Aaron figure may be Joshua. ↩

- These attempts to venture beyond the knowable recall the way the Amsterdam Haggadah “exceeds” the frame in depicting the same scene. ↩

- Sigmund Freud, Moses and Monotheism, trans. Katherine Jones (New York: Vintage Books, 1967), 144-5. ↩

- Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, trans. J. M. D. Meiklejohn (London: Bell and Daldy, 1872). ↩

- The author would like to thank Kathleen Bloch, collections manager at the Spertus Institute of Jewish Studies, Chicago, for her assistance with reproducing images. An earlier version of this article received the 2011 Goldenberg Prize for Best Essay in Jewish Studies from the University of Minnesota Center for Jewish Studies. ↩