The Indian artist Shilpa Gupta (b. 1976) was born and educated in Mumbai, where she also lives and works. Having entered into global art market very early in her artistic career, she uses a global vocabulary is related to formal and conceptual vocabulary of Western Conceptual, Minimalist, and Relational art.1 Yet her use of local hand-made paper, fake Indian administrative forms, hand-woven fabrics, and local medicine, as well as the narratives embedded in her works, ground her practice in a South Asian context. Her aim is somewhat to foreground the preconceptions which we tend to project on our environment rather than engaging liberally with it. Many of her works confront essentialist and nationalist notions of identity in the context of the violence that predates intercommunity and family life in the Sub-continent. Her work is particularly concerned with the estrangement between India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, which is cultivated by nationalist governments. She works against essentialist notions of identity as defined by social and political forces: gendered and religious narratives, and the nation-state’s logic of territoriality. She offers an understanding of identity as multi-layered, having to do with the memories, subjectivities, and affects that daily activities and human encounters map onto the mind through the peripatetic movements of the body. Her interest in the complex fabric of Indian cities, which stems from the Sub-continent’s ancient history of trade, with Europe but also with the rest of Asia (China, Japan, Afghanistan, Iran etc.), is combined with her determination to reveal the invisible bodies and wills that are the living pulse of these cities.

Her works, which manifest and celebrate the subaltern lives of those cities, can be thought of in relation to the work of other Indian artists like Anwar Kanwar or Raqs Media Collective, which are infused with a Gandhian/Swadeshi politics of love and respect for these simple protagonists, in addition to being inflected with a Marxist agenda.2 While Kanwar’s works operate, in the words of art historian Geeta Kapur, as a form of “reparation” in that they “celebrate the courage and patience” of anonymous Indians who are victims of local predatory practices,3 Raqs Media Collective’s installations have a metonymic proximity to global trade in order to condemn it.4 Gupta’s works meander between these two poles as she presents the spectator with the effects of trade on a variety of people from India, Bangladesh, Pakistan through objects that are the bearers of affects, dry, apparently neutral material that taken from the realm of infrastructure (information panels, microphones, luminous sign posts). Thus the works are both more subjective and less located than Kapur or the Raqs Media Collective.

While both the complexities of her personal background and the political aspects of her works fit with her generation’s concerns with metropolitan space and religious fundamentalism, this article will focus on works that are concerned with the subjectivity at the core of everyday life. Looking at a set of works offering narratives of actual journeys in the city, between cities, but also between social norms and politics, it will analyze the interplay between language and the materials that convey it. Her works also incorporate frames, glass boxes, light boxes, and white walls, inducing in a Western viewer unaware of the peculiar circumstances of the stories, what I claim to be a meditative stance, a reflection on the poetic of the body/mind dialogue with space and time. Using Irit Rogoff’s concept of “inhabitation,” Henri Lefebvre’s “rhythmanalysis,” and Michel de Certeau’s “practice of everyday life,” this article attempts to show that the sometimes vicarious, sometimes kinaesthetic encounter with the artworks communicates to the observer the subjective power of banal gestures, while the immateriality of the works embodies a form of invisible resistance to controlling forces. I also suggest that this body of work opens our reflection to an aesthetic of everyday life beyond the Marxist/anarchic paradigm of the “deterritoralisation of the globe”5 as a politics of resistance to global capitalism that underpins Irit Rogoff’s philosophy. I purport to link it to an “aesthetic of life” based on the concept of individual agency vis-à-vis coercive, political, economic and social forces, and to a dialogical relationship with the environment, which can be found in some western philosophers as well as in Asian aesthetics.

Shilpa Gupta’s work is embedded in the life of Mumbai, a port city on the Arabian Sea that faces Pakistan. This megapolis of 22 million inhabitants, 19% of which are Muslims, combines slums with the most advanced Indian corporations’ headquarters, traditional family life with the cultural features of post-modernity.6 It is a showcase for the “glocal” era. Mirroring the city’s complexities, the artist describes herself as being interested in multiple, diverse, and intersectional identities. She is concerned with the threat to this complex fabric posed by the rapid globalization of India in the 1990s that pushed for the uniformity of tastes and lifestyle, and by the concomitant rise of the Bharatiya Janata Party that promotes India as a nation of Hindus, shattering the Nehru spirit of tolerance and secularity. A succession of violent episodes related to the rise of religious fundamentalism marked her youth: the destruction of the Babri mosque in Ayodhya, Uttar Pradesh, in December 1992 by Hindu extremists, and the bombings and riots that followed in Mumbai, in 1993.7 In 2001 the tensions between India and Pakistan over the contested area of Kargil in Kashmir led her to initiate a public art project called Aar Paar (“this or that,” but also “through and through”) with Lahore based artist Huma Mulji. They invited artists from both sides of the border to exchange works between Lahore and Mumbai, and later, posters were emailed and printed locally to create awareness of the point of view from the “other side.”8 It foregrounds the chasm even between artists, showing how entrenched territorial policies can be.9 Gupta created a poster called Blame which depicted a bottle full of red liquid with a label that read: “Blaming you makes me feel so good. So I blame you for what you cannot control; your religion, your nationality.” In 2002, Blame became an object and a performance in which she offered people commuting on local trains to take home an actual bottle, bearing said label and filled with an ambiguous red liquid. The bottles were received with disbelief, outright rejection, but also understanding by some who took a bottle with them. Her activity led to a verbal warning in regards to the “prevention of terrorism act.” On other occasions, people walked out of a restaurant where Aar Paar posters had been placed as table mats.

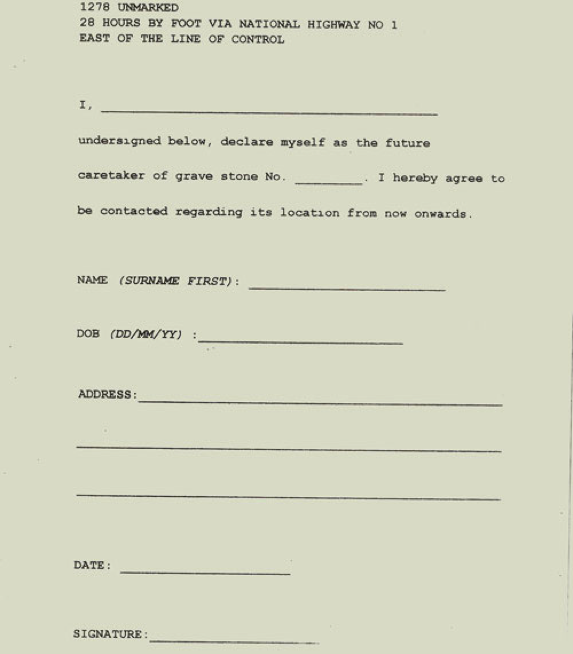

fig. 1 Shilpa Gupta, 1278 unmarked, 28 hours by foot via National

Highway No 1, East of the Line of Control,

1278 etched marble slabs, 2013. Courtesy of Chemould Prescott Road Gallery (Mumbai) and Vadehra Art Gallery (New Delhi). Photographer: Anil Rane

Detail of 1278 unmarked, 28 hours by foot via National Highway No 1, East of the Line of Control installation

Gupta travelled to contested areas in Kashmir, visiting Sinagrar and traveling alongside the border. In 2013, she created 1278 unmarked, 28 hours by foot via National Highway No 1, East of the Line of Control. (fig. 1) The work consists of a set of marble slabs that recall the gravestones used in Kashmir. A number, ranging between 1 to 1,278, is etched on each slab. 1,278 refers to the number of unmarked graves that were dug by the Indian army to receive the bodies of presumed Kashmiri terrorists who have been abducted in a single district.10 She explains in an interview:

In 2009 I came across a text about unmarked graves in Kashmir, a report called Buried Evidence: Unknown, Unmarked, and Mass Graves in Indian-administered Kashmir made by several activists including [the prominent] Parvez Imroz, documenting thousands of unmarked graves in Kashmir. The number 1278 refers to the number of unnamed and unmarked graves found in Kupwara, the district located the farther to the northwest, on the very edge of the country.11

With this work, she aims to draw attention to the events that occur in this area near the Pakistani border, far from the capital city and thus from scrutiny, where security is enforced with means beyond legal rules, “where land and people’s life have been sliced.”12 She also wants to highlight state propaganda regarding Kashmir insurgents that uses the media to present situations of insurrection in a Manichean way—as good against evil, as the nation against terrorists, as order against chaos, exploiting “anti-Pak” resentment to get away with infringements of fundamental rights. Furthermore, she wants to reveal the “invisible structures that steer the way we think in daily life.”13 The slabs are arranged vertically in four, uneven, rows. On a shelf built in a sidewall lies a stack of application forms the same unpleasant light-green colour, cheap texture, and lean, ordinary font found on Indian administrative documents. The form invites the spectator to commit symbolically to becoming a caretaker of those unmarked graves and to take a slab with them by having the following set of text:

I undersigned below, declare myself as future caretaker of gravestone N°_

I hereby agree to be contacted regarding its location from now onwards Name

Date of birth

Address

Date

Signature

The cheap paper and the lining up of the slabs reflect, according to the artist, the insensitivity of an administrative processing the victims of the conflict: “It refers to the act of filing, of measuring, of quantifying. Of defining people, place, everything! ‘You are part of this, you are not part of that.’”14 The iconic green paper on which the spectator may commit to being a caretaker, together with the seemingly careless setting of the installation (as during the exhibition After Midnight at the Queens Museum in New York)15 add to the quasi-invisibility to the whole piece: laid behind a barren wall, separated by a corridor from the main alley, and lined up as construction material in waiting, one could easily miss the slabs or could dismiss them as being insignificant.16 The green forms, casually placed on a neutral shelf, fail to attract much attention. By organizing the chance encounter of the spectator with the makeshift forgotten graves through their perambulation within the exhibition space, the artist stages the way these objects and events present themselves in real life: without a red flag, while reading the news conveyed by the media apparatus. The title of the installation underpins this allegorical journey, evoking a walk along the National Highway N°1 that connects the capital city with areas “at the edge,” where violent actions are committed in the name of security. The invisibility of the crimes is underpinned by the lack of expressivity and affect of the material. It thus remains the responsibility of the spectator to decipher the signs in order to perceive the gravity of what is addressed.

The beautiful marble enhanced with a black line and its intriguing numbering contrasts with these markers of insignificance, numbness and forgetfulness, triggering the spectator’s curiosity. When reading the text they become aware of the fact, or are confirmed in their assumption, that the slabs stand for gravestones. In this way, the crimes appear suddenly, not through carefully crafted wordings in a newspaper but as direct encounters in a field. The spectator’s encounter with the slabs echoes that of someone walking in a Kashmiri village and suddenly coming across an unusual bump of the ground, below a tree, on the side of the road. In fact, the Indian authorities use these unmarked graves, which they intentionally located in the middle of villages, contrary to tradition, as deterrents for would-be independents. As a result, no one dares to take care of them, for fear of being seen and arrested by the authorities. By creating the ‘fake’ experience, the artist heightens the spectator’s awareness of the real event. The performative process by which they symbolically commit to becoming caretakers of the gravestone contrasts with the aesthetic anomia of the paper, and by signing it, they bestow it with symbolic meaning, that of an atonement, a moral compulsion to fight forgetfulness and display compassion. Even if the spectator does not fill in the form, they are confronted with the question of moral responsibility and reminded that the power of civil society lies in individual commitment. The gesture may appear as gratuitous or lacking profound meaning when performed by a Westerners unaware of the work’s geographic and political context. However, when the work was exhibited in Mumbai in 2013,17 the audience engaged with the work in a much more immediate way: the slabs were placed in private homes rather than a gallery. Gupta says:

When the object lies in your house, may be a person visits you and asks about it and then you become the storyteller, or you might wonder and go back to look where it came from. The meaning of the artwork is related to how the observer invests into the object, which in turn is about one’s relationship to anything in fact. It is about the way context, place, memory can play on anything: it is fractured, it is personal, it is never necessarily true, it is always contested, it is always fragile. Some people took the stone because it is an artwork so there may be a sense of greed in that gesture, and also some discomfort, because of what it symbolizes: Can you live with that? Some people returned the piece because they could not have it in their house. Their parents refused to live with it. Someone by mistake broke it and was terrified. Someone buried it.18

Shilpa Gupta’s art and the narrativity of the body in space and time

This is a striking example of the way Gupta constructs her works, as nested narratives, made of successive encounters that create layers of texts and affects embedded over time in the object. Encounters between the artist and people—artists or lay persons—result in stories told and exchanged, leading to encounters between the work and its audience, and back to a dialogue between the audience and the artist. 1278 unmarked stems from the reading of a report, but also from Gupta’s visit to the Martyr Cemetery in Srinagar, where those who died in the struggle for an independent Kashmir are buried.19 She remembers “someone reading aloud the age of the boys, they were between 16, 21, 22” and “the feeling of grief” that overcame her.20 The work leads to further narratives provided by the spectators who take a slab to their home, talk about it with their relatives and friends, and report it to back the artist. According to the artist, these successive moments of storytelling exemplify the mental and emotional journey in space and time that underpins the process of thought formation. The works add a physical, kinaesthetic dimension to this mental process that both echoes the bodily aspects of mental and emotional meandering (the artist going to Sinagrar, the spectators taking the slab home), and reveal in an allegorical manner the process of becoming aware. The topoi of perambulation and encounters as a trigger for a journey of self-discovery, away from the influence of officially/socially framed narratives, is a recurring motive in Gupta’s works. It alludes to the equivalence between walking and the meandering of ideas, the enfolding of affects, as in language. Indian culture, be it religious, literary, or visual, emphasizes a dialogical relationship between space and time as a way to access truths that are beyond the illusions of the real. This is at the core of the Mahabharata, the great epic poem about spiritual enlightenment, but it is also seen in folk storytelling traditions as in Patua paintings. It structures Indian classical music, which is based on a circular repetition of motives, or raga.21 Gupta affixes this liberating role to objects of daily life rather than aesthetic artifacts. She says:

I am interested in perception and therefore the creation of knowledge and aspirations in our daily life…It could be an object we desire in a shop window, the way we look or make assumption regarding a particular group or community…I am interested in the multiple meanings which an object can embody, and the shift that can take place from different positions.22

Her interest in daily life as a subversive narrative is also central to her contribution to the 2015 exhibition My East is your West.23 Among her several installations the “Enclave project” (Untitled, 2013-14) displays drawings, videos and photographs related to territories along the border between India and Bangladesh, which for complex historical reasons, are enclaves of Indian territories within Bangladesh and vice versa. The result is an administrative limbo of Kafka-esque proportions.24 The works are the result of an ongoing survey by the artist of people’s lives in some of these locations. She traces the flow of people and goods (cows, SIM cards, DVDs, gold) sometimes smuggled, sometimes lost in the no man’s land between frontiers. According to Gupta, this flow of goods serves as testimony to an unstoppable will to survive. A series of drawings is made with a transparent codeine-based syrup, a medicine that is legal in India but illegal in Bangladesh. A small text appears at the bottom of each drawing. The font used for this text is the same administrative font used in the 1278 unmarked installation. The texts are ridiculously humorous, yet a reflection of actual administrative orders. They underpin the absurd attempts by local authorities to regulate the flow between the enclaves and the borderland more generally. One drawing represents a fenced frontier, with a horizontal line marking the land, and a vertical pole indicative of the pillars that support barbed wire. The text below says: “India is building a fence which is 150 yards inside the zero line. Often cattle taken for grazing here, crossing the Border Security Force post, is reported missing at the local police station.”

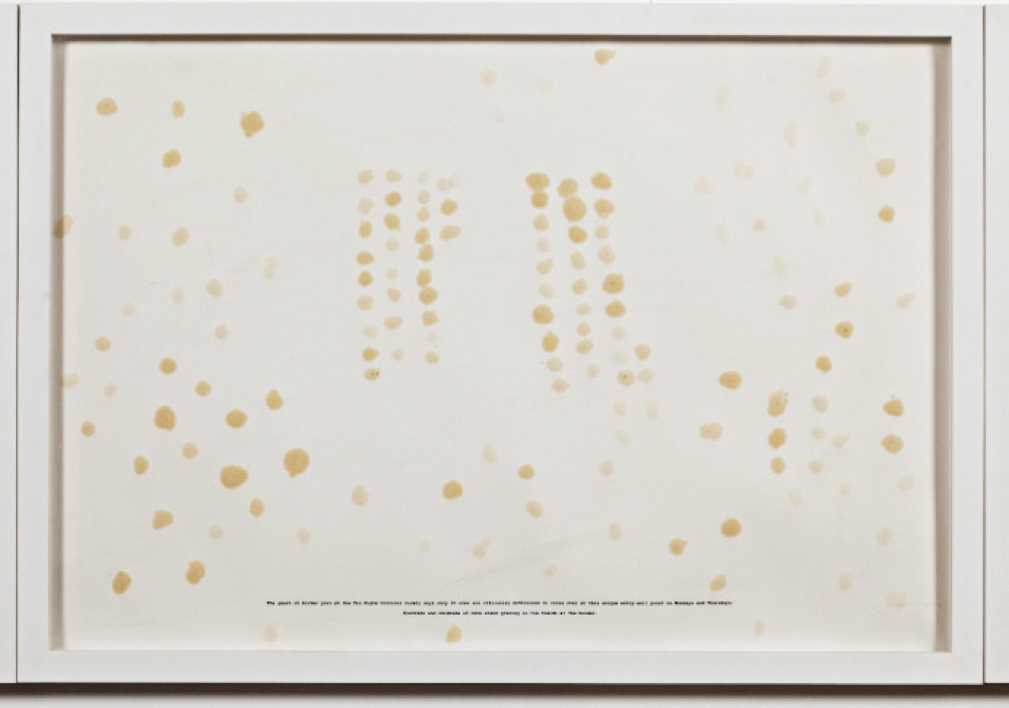

fig. 2 Shilpa Gupta, Untitled, 2013-2014,

Drawing made with Phensedyl, codeine based syrup, 38 x 56 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Galleria Continua (San Gimignano, Beijing, Les Moulins, and Havana).

Photographer: Anil Rane

Project co-support: Samdani Art Foundation

Below a drawing made of dots of various diameters aligned in several rows, the text reads: “The guard at border post at the Tin Bigha Corridor firmly says only 30 cows are officially authorized to cross over at this unique entry-exit point on Mondays and Thursdays. Hundreds and hundreds of cows stand grazing in the fields at the border.” (fig. 2) In yet another drawing, a soccer game takes place between border guards and the people of the enclave. “Is it all right if we win?” asks the text below the drawing, in which the players and the ball, made with codeine, are almost invisible. Beyond the mockery of absurd administrative regulations, the artist’s intention is to underscore that life goes on in these zones of administrative limbo: “Daily life in the borderland belies state intentions and the flow of people and goods continue, prompted by historical and social affinities, geographical continuity and economic imperative.”25 In other works, Gupta attempts to symbolically re-establish a territorial continuity between Bangladesh and India through installations that narrate the exchange of goods between cities on each side of the border, such as Dhaka and Calcutta or even Mumbai. Untitled (2015) relates to the importations of famous hand-woven sarees from Dhakai Jamdani in Bangladesh, which are brought across the border by foot and then by train to Calcutta, where demand persists across generations, despite Partition. The piece consists of a shredded fabric rolled up on a stick and displayed in a transparent museum pedestal. A text typed in a dry, Courier New font, is placed in the case, in the manner of old-fashion Arts and Crafts museums. Yet the text has no explanatory validity. The font imitates that of mechanical typewriters, still in used in India’s rural zones. The mimicry includes erasing the name of the village by typing the letter x over the central letters. The text narrates a journey:

Three hours and an overnight train journey

Rxxxi giram village to Kolkata city

Walk, train

5 pm to 11 pm, Since 29 years

Across 2900 km of fenced border

300 to the dalal middle-man who passes

200 to customs 100 sarees to sell. To be worn

The artist explains: “The fabric has been shredded and wrapped around a stick, a walking stick, a combat stick or a stick off the loom may be. Wrapped on to it, over and over again, it morphed so that its original reference to a saree slips in a state of doubt.”26 The text is drawn out of a conversation between Gupta and an intermediary who carries the sarees across the border. There is an intriguing contrast between the muted piece, which resists the spectator’s understanding, and the story of a journey. The hermetic and conceptual composition evokes Joseph Kosuth’s assemblages, which Gupta has been interested in since her students years,27 where a text, similarly arid and abstruse, is a vessel towards an invisible realm, that of the mind, beyond the material and the practical. One and Three Chairs (1965), which Shilpa Gupta has seen,28 conflates an actual chair, a photograph of a chair, and a text describing a chair, akin to a commercial or museum labels. The text regarding the chair underpins the authority ascribed to explanatory texts and their capacity to condition the mental representation of an object. The photograph, with its soft lighting, somewhat liberates the spectator from this enforced idea and leads him/her back to the memory of the experience of the object. This process shares an affinity with Husserl’s method of “reduction” whereby the ego, according to Nathalie Depraz, frees itself “from the object in order to take note of the act of consciousness directed towards the object…allowing another dimension to emerge from it…which precisely frees the ego from the ordinary pre-givenness of the world.” To do this there is a need to practice an epoche, i.e. “a gesture of suspension with regards to the habitual course of one’s thoughts, brought about by an interruption of their continuous flowing.”29

Like Kosuth’s composition, Gupta’s work structure also facilitates this epoche. Contrary to Kosuth’s work, the text in Untitled (2015) is the agent of liberation of the spectator’s imagination while the object is the element of conceptual resistance. The abstruseness of the object and its apparent lack of relation with the text creates a chasm between the spectator’s expectation of an artwork in a glass pedestal, and what they actually see and read. This precludes many definite understanding of the object and from seeing the text as an explanation. Deprived of their expectations of a cognitive content the spectator is opened to the narrative conveyed by the text, a trip in a train between a village in Bangladesh and Kolkata. By narrating the story of this journey, with a font that points to a mechanical typewriter, to the successive gestures of typing singular letters to create a sentence, the text induces a virtual kinaesthetic experience. The font echoes the rhythm of the dry clapping produced by the metal pad punching the paper and, by metonymy, of the regular beat of the train wheels on the rail tracks, while we imagine the gentle breathing of the man walking, and then sleeping during this “overnight train journey.” The device reinforces the sense of time implied by a journey across a territory, but also unites a private, “secret” rhythm (that of the breathing) with a public rhythm (the train tracks), through the typing of the story.30 The text thus transforms the space travelled into time, and associates the journey with a unique individual experience—that of a man sleeping through the night in a train and reconvening with himself. The train figures prominently in Indian imagination, both as charting the map of the Sub-continent, as linking remote territories, and finally as a marker of Partition. Gupta avidly read Khushwant Singh’s 1956 novel A Train to Pakistan in which the train across the border functions as a sign of hatred and crime between former neighbors and economic partners. Her work seems to be healing this chasm by transforming hate into a trading partnership again.31 The text resonates with the shredded sarees smuggled between Bangladesh and Kolkata, while pointing to an individual agency in achieving this healing. This hermetic allegorical mode suggests that some memories cannot be grasped through the object, just as the flow of life cannot be morphed into objects. Language, on the contrary, is able to reconstruct the unity between body and mind that is the bearer of our unique experience of the object in space and time. Here the text, thanks to its typing, is embedded with the fabric of life, with the contingency of mind/body association, which is, according to Moshe Feldenkrais, the only way to perceive our inner being: “We have no sensation of the inner workings of the central nervous system; we can feel their manifestation only as far as the eye, the vocal apparatus, the facial mobilization and the rest of the soma provoke our awareness. This is the state of consciousness!”32 Gupta explains: “I see the senses as a medium to transmit to us what we recognise, but they also transmit to us what remains unrecognizable. I am interested in emotions, or lack of it, and memory and its residue.”33 Just as trade is both an act of political resistance – against borders– and of psychological resilience, the work is an act of liberation of the spectator’s mind from the conditioning of the museum experience. It creates a chasm between the case, the object, and the text. In this way, we can also relate its formal and semiotic setting with the Grapefruit poems by Yoko Ono. In “Snow piece” (1963), she writes: “Think that snow is falling. / Think that snow is falling everywhere all the time. / When you walk with a person think that snow is falling between you and on the person. / Stop conversing when you think the person is covered by snow.”34 The two works share a similar layout that emphasizes the blank parts of the paper—a minimal, austere font that underpins the void versus the black line—interrupted sentences and grammatical discontinuity that point to the silence between words, all to the effect of conveying a sense of incommunicability. The similarities are no accident. Gupta is appreciative of Ono’s art and was offered a copy of Grapefruit by a friend who saw similarities between their work.35 The two artists share a common sensitivity to an “inward view of the self,” that is informed by Zen Buddhism. Yet, contrary to Ono’s haiku-like texts that evoke a private encounter, Gupta’s text conveys the experience of a vernacular journey over the border, involving walking, paying a middleman and spending the night in a train. The journey of the trademan is transformed through her text into an inner journey in as much as a displacement on a territory. It conveys, through its form, the sense of freedom that being in-between produces, especially during long hours on a train, which Freud compares to the psychoanalytical process: “So say whatever goes through your mind. Behave in the manner of a traveller who, sitting by the window of his compartment, describes the landscape as it unfolds to a person placed behind him.”36

Shilpa Gupta’s works are indeed a reflection of the narratives generated by people appropriating the space they live in, in spite of official boundaries, through their bodily and sensory life. The work suggest that traders, importers, exporters or smugglers create communities and sustain life through their displacements across towns and frontiers, which they subvert. The travelers seem bestowed with the ability to roam freely through a physical, economic, and by extension, imagined territory. Gupta has collected these stories while sojourning on the terrain. The work later conveys this imagined territory to the spectator’s imagination where it can trigger their own experiences of traveling. Gupta says:

I am interested in walking. It seems that we became humans when we were able to stand and walk and had the ability to look into a stone and see a tool. Movement is one of the most basic actions that we do. Birds move, people move. The border is often only at the check post. And people move and it’s especially hard to contain this, over an uneven terrain that is punctured with rivers and more so, with human need and often desperation. The informal, illegal trade is part of the daily life in the borderlands, where the border both constructs and subverts the state.37

Shilpa Gupta and Irit Rogoff’s “inhabitation”

Gupta views migrations of people and merchandise as capable of opposing the artificial confines of nation-states and global capitalism. Her projects emphasize trade as fostering a trans-national community. We may understand her works and statements in a materialist sense, as proclaiming that work forces (infrastructure) create cultural representations (superstructure), a concept central to Marxist theory. For Louis Althusser, this appears as a deliberate process organized by the dominant class through the state apparatus.38 For Marxist anthropologists it is a spontaneous process, stemming from everyday life. Leslie White posits in The Evolution of Culture (1959) that: “A culture, or socio-cultural system, is a material, and therefore thermodynamic system.” It is subjected to laws of conservation and expansion of energy, which also control “the movements of commerce and industry, the origin and wealth and poverty.”39 In Terra Infirma (2000), Irit Rogoff also evokes transnational, but strongly knit communities of traders, as being capable of countering the homogenizing model of globalization.40 She gives the example of Indian communities photographed by Indian artist Gauri Gill in Kabul “who have been living in Afghanistan for hundreds of years, as traders, who speak Dari Afghan language,” but have moved to India “and still dream of Jalalabad.”41 Referring to the curatorial projects of Bengali Anshuman Dasgupta, Rogoff also argues that the “‘zones of disidentification’ or ‘no man’s land,’” like Kashmir or West Bengal, are such transnational space as “people pay less attention to being on this side or that side of the border; because it has economies, because they’re porous, because of weird little things that float in and out of both sides.”42 Rogoff compares the process of “gliding through border lines” to smuggling, as they both “[operate] as a principle of movement, of fluidity and of dissemination that disregards boundaries” by creating “a performative disruption that does not produce itself as conflict.43 For Rogoff, smuggling is a form of embodied resistance to dominant economic systems.44 It produces “bottom-up knowledges, partly experimental, partly theorized, that allow us to rethink maps of what we think we know.”45 It is more efficient than a Marxist top-down criticism of neo-capitalism, and goes beyond the concept of hybridity that is based on the centrality of the subject. She names “inhabitation” this collective agency based on trading, of “foods and textiles, sounds and literature,” on “stuff circulating.”46

We may understand Gupta, who herself comes from the Agrawal community, as leaning towards this interpretation of trade “of foods, textiles and artworks” as producing “bottom-up knowledges.”47 She is well aware of the politics of trade and smuggling, as it has been discussed in several texts and exhibition catalogs written, in particular, by Geeta Kapur. By insisting on specific physical locations and action, Gupta aims to oppose the forces of global capitalism, its dematerialization of life, and its destruction of local communities. She says:

Physical location is one of the many entities that determine the functioning of the human brain…We have entered a great watershed moment today, where the roots of all locations are floating freely in a deep glocal sea, whose shores touch the east as they touch the west, and individuals gravitate to their own islands as per their own aspirations, their own politics, and as perchance too…The East is feeling distressed about this more acutely today, as social space is extremely close knit in this region, with several generations still living together under the same roof.48

Shilpa Gupta and Henri Lefevbre: Rhythmanalysis

While she shares Rogoff’s valorisation of trade as performative, Gupta’s concept of the latter seems somewhat different. The quiet, often meditative tone of her works relates to individual journeys and unique encounters, suggesting a complex relation between the singular and the plural. I would like to locate her ambivalent position firstly in relation to Henri Lefebvre’s own ambiguities. In The Production of Space (1974) Lefebvre, following Marxist orthodoxy, was critical of the concepts of “mental, subjective and philosophical spaces.” There is but one category of space, he argued, that of the forces of production which determines the “social relations of production,” and their cultural representations: “We are concerned with logico-epistemological space, the space of social practice, the space occupied by sensory phenomena, including products of imagination such as projects and projections, symbols and utopias.”49 For Lefebvre, “everyday life is central to the reproduction of capitalism insofar as it is saturated by the routinized, repetitive, familiar daily practices,”50 that induces boredom, submission to habits and social conventions and therefore are the best “guarantee of non-revolution.”51 This dynamic process can be inverted to produce a revolution of the minds. Culture—especially poetry and visual arts—and an awareness of our ordinary gestures can reverse the cycle of alienation and reveal “not our internal consciousness” but the consciousness of our actions “directed towards specific goals” which he calls “thought-actions.”52

In Rhythmanalysis, his last book of 1992, Lefevbre, who by then had distanciated himself from Marxist doxa, studies the “sensible”, the “individual inner consciousness” and the body—all of which are anathema to materialism and to metaphysics—through what he considers to be their commonality, rhythm. The “rhythmanalyst,” he contends, is like a psychoanalyst—he listens to the “noises of the world” as well as “murmurs, and finally to silences,” and looks at the “dominating-dominated” relation between the two. He becomes aware of the differences in rhythms between people and things (the forest, the sky, a stone), in order to release “the sensible” perceived through the “concrete experience” of the moment.53 Gupta also argues that emotions and their representations are related to action,54 but rather than emphasizing “conscious thoughts” or “thought-actions” geared at a (mostly practical) goal, she insists on the “secret” thoughts that occur in the vagabondage of smuggling, on the “murmurs” produced by people of an enclave playing soccer with the guards at the border, on the rhythms of the slabs of Kupwara, staked against one another that oppose their affective charge to the rational of the administration. Shilpa’s objects are bearers of the affective memories of both the individual and the collective, that lie hidden in the “in-between” of events, of borders. She says: “I am interested in the functioning of the human mind, the individual vis-à-vis the group, and the nation-state, beyond and in between, and how does it change when the zones shift.”55

fig. 3 Shilpa Gupta, Speaking Wall, 2009-2010,

Interactive sensor based sound installation, 300 x 300 x 300 cm

LCD screen, Bricks, Headphone, 8 min interaction loop. Courtesy of the artist and Galleria Continua (San Gimignano, Beijing, Les Moulins, and Havana)

Her works allude not only to exchanges taking place in the social environment, but also to transactions—often unconscious and unacknowledged—that occur between the outer world and the inner self. She says, “What we see and how we see is very subjective, very context based. I am interested in the conscious and unconscious space that lies in between the object and the formation of meaning.”56 Thus, a second layer is added to the notion of frontier which is central to her work: while the first is the frontier which separates communities enforced by national and religious narratives, the second concerns the internalized narratives and psychic maps they create. This concern is not unique in India, and also appears central to Anshuman Dasgupta’s curatorial projects and to the films of Amar Kanwar, an artist who Gupta deeply appreciates.57 Yet her unique contribution consists of conveying this experience of territory and imagined maps from local communities in India to an international audience through the vocabulary of conceptual art, helping bridge the two distinct social contexts. In Speaking Wall (2010), the spectator is enticed to step onto a narrow line of bricks–strikingly similar to Carl Andre’s Equivalent VIII (1966)–to walk towards the wall and to put on headphones. The wall has an embedded distance sensor that detects how far or how close the observer is from it (fig. 3). The sensor activates the artist’s recorded voice (the words of which can be read on a digital panel on the wall) which gives the spectator instructions, through the headphones, to move towards the wall (One step back / One more), or away from it. Between two sets of orders, the voice alludes to the presence of an invisible wall, of a lost house, during an eight minute loop. The alternation of instructions to move with the description of an invisible scenery emphasizes the chasm between “the here” “the body” and “the over there”, the imagined space. A contrast is enacted between “thought-actions” and inner consciousness, between immediacy and elapsed time. The contradictory nature of the quality of awareness triggered by those successive moments is actually liberating, possibly because of the aforementioned body/mind coordination. At one point, the voice becomes commanding and says: “Step away one step / March forward one step / One step.” Then with a softer tone: “Now you no longer stepping on the border … the wind shifted it by a few centimeters.” More orders follow and then: “Yes / Now you are on the line / where I last night made the border / But since it is raining today / It’s a bit difficult to see.”58

While the commanding voice-over and the digital panel evoke state control, the soft, feminine voice of the artist resists the rational paradigm on which this control is based, as chance, poetry and embodied sensation come to mark the border that moves with the wind and is erased by the rain. The question of who takes care of a grave that lies beyond the border, who has the keys to a house, is also part of this narrative. The voice asks:

Did grand mom come / from your side onto my side / to visit our mothers grave?

Ah, she must have / Still got the keys to the house

What do I do? / She took the keys And walked / forward a few cms more / And the rain shifted / the border last night

I am no longer able to enter my house.59

The inspiration for Speaking Wall stems from a conversation with Pakistani filmmaker Farzad Nabi during an automobile trip in 2005, back to Lahore from Wagah, a frontier town where highly ritualised ceremonies of opening and closing of the border gate take place daily.60 Nabi mentioned a house on the Indian side of Punjab, a house his family owned prior to Partition and of which his grandmother has the keys till that day.61 The house, the keys, and the grave construct an imagined space that disrupts the official lines of separation. The border becomes a sacred space associated with the cult of ancestors, an actual Patria, a territory attached to a family lineage. The concept of rhythm here is essential: that of the steps with the sound, of the body with the wall, and the independent rhythm of the rain, that escapes boundaries. The installation foregrounds the distinct rhythms that pulse in each singular element. It organizes their encounter and produces a eurythmic harmony in place of arrhythmia, and thus a healing. This again suggests a proximity with Henri Lefevbre’s rhythmanalyst who “listens to the inside and outside of observed bodies,” sees them “as a whole” and attempts to “unify them…by integrating the inside and the outside” in order to produce a “eurythmia,” a “metastable equilibrium” where there were “disturbances (arrhythmia).”62 The imagination of the displacement along the border, in a house and a collective space of dwelling (of living and dying) is nurtured by the rhythm of physical movement instilled by the installation. It is itself the result of the interaction between the rhythm of the voice, the observer’s listening, and their bodily reaction.

Shilpa Gupta and Michel de Certeau “anthropological space”

Because Shilpa Gupta’s work deals with displacement in a social realm, it is productive to read her works alongside Michel de Certeau concept of “anthropological space,”63 a “space as practice.” Certeau, a former Jesuit, ascribes spiritual dimension to inhabiting a space. It is a strategy of resistance by the anonymous, the overlooked individual. Using the allegory of a person shopping on the main street, Certeau suggests that each perambulation is unique and triggered not only by material constraints but also but affective and emotional needs (such as crossing the street after shopping at the butcher to say hello to the florist). This “walking…is indicative of a present appropriation of space by an ‘I.’”64 It produces a unique, performative mental image that reflects individual agency on the space the subject inhabits. This meandering characterizes the “relation to the world” of each individual, and as such “there are as many spaces as particular spatial experiences.”65 These subjective spaces are made manifest by first-person narratives which he calls “pedestrian speech act,” as when people describe their apartment from the point of view of their everyday experience of walking, from the corridor to a room, to another. They would use words related to vision such as “If you go straight ahead, you’ll see . . .” They use expressions related to a succession of actions (“There, there’s a door, you take the next one”) rather than a neutral description of the layout.66 This speech act, says Certeau, not only posits an “I” but also creates a sense of community as “it has the function of introducing an other in relation to this ‘I’ and of thus establishing a conjunctive and disjunctive articulation of places.”67 We find this exact same pattern in Gupta’s Speaking Wall, and it is striking that this installation originates from a conversation with Farzad Nabi, in which he conveyed his personal and familial memories of inhabitations, during a trip in a secluded space, a car. Shilpa’s installation acts as a transmitter of those memories to the spectator’s imagination through a body-mind experience. In that sense, the citation of Carl Andre’s Minimalist brick pathway—though overlooked by the artist—becomes meaningful, given Andre’s concern with walking and meditation. To Andre’s emphasis on inner thoughts, Gupta adds the function of communicating with an invisible community. Referring to oracles, Certeau says that a story is first of all an authorization to undertake action that gives it a “foundation.” It is sacred as it ensures that action will be beneficial, auspicious.68 As a sacred act that ensures a favorable outcome, “a narrative activity, continues to develop where frontiers” and “the marking out of boundaries” are concerned.”69 Speaking Wall is certainly a narrative about a frontier, about Partition. It seems to point to the lack of an auspicious foundation in the creation of the frontier between India and Pakistan, and to the genocide and endless war that it entailed. It may be suggested that Gupta’s narratives, which blur and shift the frontier, redeem history by belatedly reconstructing a space in which graves are reunited with their caretakers, people with their houses, family members with their estranged land.

A text by Gupta called A Drawing made in the dark-1 (2015-2016), further underpins this essential role of body-mind relationship in her works. It reads:

Go straight. Turn right at the tea stall and carry on to the main road.

Then after the church, you will see a Border Post pillar on your left.

Walk across the field, past another pillar, belonging to the other side

and you will see a shop selling wood.

It’s the third house from the junction there.

The text is like an instruction sheet made by one trader to guide another. It also testifies to the mental representation of the path, which is created by walking: “It’s like you know the journey so well, you do it so often, that you can draw it while closing your eyes,” Gupta explains.70 In both this work and Speaking Wall, the narrative acts as a bridge between two subjectivities, that of an actual walker and that of the spectator, through the means of the latter’s body. In Speaking Wall, the spectator physically moves according to the instructions and is then made to imagine a unique space and time, a house under the rain, a wall, a grave, a set of keys, through the narration of the voice. The artist foregrounds the distinct rhythms that pulse in each singular elements (the spectator, the wall, the voice, and indexically, the rain, the house, the frontier). In Drawing, the words printed on the paper act as a bridge between a physical journey and the imagination of the spectator who moves vicariously, following the movement of their eyes as they read the text. The sense of movement is given by the rhythm of reading that is itself the result of the interaction between the spectator’s reading rhythm (it varies from one person to the other), the layout of the text on the paper, and the semiotic meaning. They all combine to convey the remembrance of a walk. This second work sheds light on the difference between reading a map—a cognitive and abstract operation—and walking a territory. In the latter case, affective elements, such as drinking a warm teacup, chatting with the shopkeeper, walking across a field and feeling the scratches of the grass, become embedded in the memory and reactivated by the reading. It suggests that the accurate representation of this kinaesthetic process would be a map, which units of measure that reflects the speed and direction of the displacement of the body through space. The plans made by Le Corbusier for the Capitol of Chandigarh in 1964 have such a unit of measure (they are based on steps of 80 cm). By changing the unit from an abstract concept (the meter) to one based on steps, Le Corbusier wanted to make visible people’s lived experience of walking through a space, between buildings to which he ascribed a sacred symbolism.71 He was thus reverting to a pre-modern way of mapping. Portolan charts, the medieval maritime maps made by Mediterranean pilots (portolani) and used between the 13th and the 18th century, are examples of such pre-modern maps. They are not based on a system of abstract coordinates and astronomical observations, as later one, but on distances, estimated according to the duration of the navigation, and a direction given by the compass, in a bottom-up process. Their scale is given by a unit of measure that is only visual (a segment) but not explicit. Hence the distance between two locations can only be calculated by comparison with the distance between other locations, within each map.72

fig. 4 Shilpa Gupta, Untitled, 2015

Carbon rubbings and incisions on paper, 45.72 x 68.60 cm.

Courtesy of the artist and Galleria Continua (San Gimignano, Beijing, Les Moulins, and Havana)

Photographer: Ela Bialkowska

It can be claimed that these techniques of measurement based on the actual displacement of bodies (or vessels) disrupt the modern conception of maps, constructed by geographers away from the terrain, through astronomical calculations and today with satellite observations. This is what Shilpa Gupta attempts to do in 1703 km of Flood Lighting—Department of Border Management Home Ministry of India (2015-16) a work placed next to A Drawing made in the dark-1. (fig. 4) The former is made by creating a (fake) map of lightning posts along the border with Bangladesh. The artist used carbon paper and a crayon to create this map, puncturing the paper to create the lightning posts. She says, “I have always been interested in light—what we know and what we don’t. Here, carbon paper, which is used to duplicate something, to make a copy, often for keeping records, has been rubbed again and again on the paper, which is then punctured through.”73 The result is a mesmerizing work that seems made with a blue crayon. It irradiates a diffuse light, as if one was walking on this well lighted road, under the rain or in the fog. The tiny punctured holes reveal the white paper underneath, and glide like stars. It conveys a sense of uncertainty mixed with clarity, but also of threat, as when one approaches a border inundated with lights of control at night.

fig. 5 Shilpa Gupta, 1:998.9, 2015 Installation view of My East is your West, Palazzo Benzon, Venice, Italy, 2015

Courtesy of the artist. Photographer: Mark Bowler, Gujral Art Foundation

Commissioned by Kvadrat

The installation 1:998.9 (2015) (fig. 5 and 6), completes Gupta’s endeavors to rewrite borders metaphorically. Upon entering the room, one sees a performer at a table drawing lines on a piece of hand-woven cloth, by pressing a stick on a carbon paper. On his left, lies as a massive, coiled white mass of fabric. The cloth comes from Phulia, a border town famous for its fine textiles. The man, who seems to be of South Asian origin, examines the tissue and draws on to it, making a succession of marks.74 He then shifts the fabric to the right by a few centimeters. It takes several weeks for the large heap of white fabric to be processed. The cloth is 3,394 meters long, a precise 1:998.9 of the length of the actual fence being built at the border between India and Bangladesh, which the artist claims is the longest security fence in the world between the two nation-states. This fence aims to protect India against terrorism and smuggling, but also creates a potentially lethal barrier for the population of the wetlands in the Bengal Delta who live in a volatile environment that is subject to the effects of climate change.

fig. 6 Shilpa Gupta, 1:998.9, 2015, Installation view of My East is your West, Palazzo Benzon, Venice, Italy, 2015.

Courtesy of the artist. Photographer: Mark Bowler, Gujral Art Foundation

Commissioned by Kvadrat

1:998.9 appears as a metaphorical contestation of the barrier that, when finished in 2017, will limit the flow of people. It can also be perceived as the replay of the drawing of the border between the two countries, made hastily in July 1947 by the Radcliffe Commission under the stewardship of British officials. To a panoptic view of the territory, it opposes a repetitive, slow gesture made by a (fake) local, who draws lines according to his own inner rhythm. The work is not related to the Radcliffe Line, nor to a particular line, though: “They could be lines in your hands, lines on the ground, mountains, rivers, it could be map lines, lines of people walking routes, as in Drawing in the Dark; but always crisscrossing each other. It is related to a map, but mental as well as physical. It is quite indefinite and it has many meanings. It is a map line but not a map line, the things which are not on maps – which are also maps,” Gupta explains. The bizarre choice of scale, a little off from a rounded 1:1000, also “deals with a sense of inherent doubt with the large scale mapping exercises that get undertaken,” she adds.75 The work is a narrative of individual freedom and the right of any living being to disrupt officially sanctioned territory.

Her proposal strongly echoes Certeau’s assertion that:

Surveys of routes miss what was: the act itself of passing by. The operation of walking, wandering, or ‘window shopping,’ that is, the activity of passers-by, is transformed into points that draw a totalizing and reversible line on the map…The trace left behind is substituted for the practice. It exhibits the (voracious) property that the geographical system has of being able to transform action into legibility, but in doing so it causes a way of being in the world to be forgotten.76

To the utopia of the modern city and its rectangular grid of large avenues, Certeau opposes places “haunted by many different spirits hidden there in silence, spirits one can ‘invoke’ or not,” “the only places where people can live.”77 Similarly, Gupta’s arrangement of the exhibition space for My East is your West in Venice is a journey in the dark. Windows have been obliterated by shutters and fabric. There is but a dim light projected on singular works, forcing visitors to discover one artwork at a time, through a slow walk, and to somehow internalize the invisible journeys of the anonymous traders, smugglers and enclave settlers that are presented to their view.

Within the exhibition in Venice, there was an indication here in one room, then another indication is in another piece so that you put together things slowly, and something is held back and not immediately revealed. It is like being in the dark, you slowly make your way and you never really know everything. I wanted to create a kind of a silence around the pieces. I often treat my works in a similar way, where I leave the room dark and shed light only on the piece.78

Certeau ascribes a spiritual dimension to these anonymous journeys, the drive to mark the world with one’s imprint, however minimal and invisible. There is an implied Christian mysticism in this celebration of each individual mark on the modern urban territory, as the symbol of the unique importance of each soul, however ordinary.79 It somewhat differs from Gupta’s philosophy of life—her perspective as an Indian is informed by the persistence of a strong collective life. Yet the common point is the celebration of subaltern, ordinary, vernacular imagination and subjectivity, emerging from actions and interactions with objects.80 Like Gupta, Certeau posits that everyday, bodily displacements are a form of resistance of an “I,” as humble as it may be, against “technocratic” rules:

As unrecognized producers, poets of their own acts, silent discoverers of their own paths in the jungle of functionalist rationality, consumers produce through their signifying practices something that might be considered similar to the “wandering lines” (“lignes d’erre”) drawn by the autistic children studied by F. Deligny…In the technocratically constructed, written, and functionalized space in which the consumers move about, their trajectories form unforeseeable sentences, partly unreadable paths across a space…the trajectories trace out the ruses of other interests and desires that are neither determined nor captured by the systems in which they develop.81

In this sense, Certeau’s text helps us see Shilpa’s works beyond the contingencies of the local, the historical and the political. At the core of this take on displacement is the celebration of individual agency.

In conclusion: Shilpa Gupta, Michel de Certeau and Henri Lefevbre

It appears that Gupta’s works contain a transnational narrative, in which frontiers are presented as arbitrary limits that create hatred, prejudice, and violence. They suggest that these prejudices can be overcome by a celebration of community-based identity, performed through the exchange of people and goods, ranging from basic medicine to expensive sarees, a process that Irit Rogoff has conceptualized as “inhabitation.” Yet, as traces of a subject-based displacement through space and time and of the inner reverberation, which they produce in the traveller’s mind, her works can be better understood through the notion of the “pedestrian speech act” coined by Michel de Certeau.

Certeau and Lefevbre both point to the body-mind relationship as a process of asserting the “ordinary gestures” of the ordinary individual against social structures. While Certeau insists on an anthropological and metropolitan environment as well as on a relationship between the mind and the space, Lefevbre enlarges the frame to all “sensible” realms “everywhere where there is interaction between a place, a time and expenditure of energy.”82 While Certeau looks for the marking of one’s trace on the territory, implying a chasm between the subject and the space, Lefevbre advocates a search of “eurhythmy” between the individual body and its environment, not only an urban and social but also natural and animal, which is at the core of Gupta’s works.

In recreating these inner spaces, speech acts and rhythms in her installations, as well as in allowing the visitor to explore them in a solitary way, through their own perambulation, Gupta produces an aesthetic experience in which invisible memories and affects constructed by “being in the world” are reactivated, presented to one’s consciousness, and reflected upon in a phenomenological manner. Simultaneously, the ties between a singular individual in the world and the community are revealed as a condition of being. Here lies her thorough dismantling of invisible borders.

If this work is well received in a wide international context, both Western and pan-Asian, it might be because a common perspective on the body-mind relationship and of the aesthetic of everyday life has emerged since the 20th century, that reunites Western and Eastern perspectives. This article discusses Shilpa Gupta’s work with the help of Western thinkers but could have also considered Indian, Japanese and Chinese perspectives on “everyday life” and their understanding of the relationships between the individual and the environment.83 This common interest in “becoming aware” of the rhythm of the body and its relationship to the space will provide further nuance and enrich the understanding of Gupta’s works.

- Gupta studied sculpture at J. J. School of Fine Arts in Mumbai between 1992-1997 which was then very traditional and inward looking. Despite her little exposure to international art she started doing experimental work using everyday readymade material. She joined the roster of the newly opened Gallery Sans Tache in Mumbai, participating in Miniature Format Show, in 1997 and in Altered Altars (three person show), at Mumbai Lakeeren Art Gallery, in 1998. Her participation in Century City: Art and Culture in the Modern Metropolis at Tate Modern, London, curated by Iowna Blazwick, Geeta Kapur and Ashish Rajadhaksha in 2001, launched her international career. ↩

- For a history of this development of Indian art see Geeta Kapur, “Secular artist, Citizen artist,” in Art and Social Change: A Critical Reader, edited by Will Bradley, Charles Esche, 422-439. London: Tate, 2006. Accessed on Art Asia Archive, http://www.aaa.org.hk/Collection/CollectionOnline/SpecialCollectionItem/21054. I am here referring to Kanwar’s The Lightning Testimonies, 2007 and The Sovereign Forest (2011-2015), the latter being made in partnership with a local NGO The Samadrusti. ↩

- Geeta Kapur. “Tracking,” in Indian Highway. Lyon: Museum of Contemporary Art, 2011, 287. Exhibition catalog. ↩

- See for example Escapement (2009), a mixed media installation showing twenty-seven clocks with major world cities time, as in international hotels or shops. In the centre, a cubicle TV set shows the face of an expressionless young person. The numbers in the clocks have been replaced with words such as epiphany, anxiety, guilt, fatigue, fear. The work hovers between a criticism of globalization as numbing and a catchy globalized search of comfort in psychological well-being through an “awareness of our negative emotions,” The ambivalence of such works has been documented in particular in Hans Belting, Andrea Buddensieg and Peter Wiebel, The Global Contemporary and the Rise of New Art Worlds. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2013. For specific section in which work is discussed, see page 334. ↩

- Geeta Kapur argues that this idea is the expression of a “anarchist utopia, euphorically pitched into a form of futurism.” See Kapur, “Secular artist,” 439. ↩

- She laments the proliferation of “Gucci and Louis Vuitton shops which followed McDonald’s.” See Stine Høholt, “Interview with Shilpa Gupta,” in India: Art Now. Edited by Christian Gether, Stine Høholt, and Ruggard Juul. Ishøj: Arken Museum of Modern Art; Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2012, 89. Exhibition catalog. ↩

- Regarding the destruction of the mosque see the disturbing video of the events on YouTube, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h_zXGXMzQxo. Accessed April 18, 2017. A description of the complexities of the phenomena in the context of Mumbai is addressed in Geeta Kapur and Ashish Rajadhyaksha, “Visual Culture in an Indian Metropolis,” Asia Art Archive, 2003. Accessed May 5, 2017. ↩

- Hammad Nasar, “Lines of Control: Partition As A Productive Space,” in Lines of Control: Partition As A Productive Space, edited by Iftikhar Dadi, Hammad Nasar. Ithana, NY: Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art with Green Cardamom, 10. Exhibition catalog. ↩

- Significantly, a map of Kashmir made by artist Roohi Ahmed, Hum, in 2002, appeared as too sensitive to be shown in Mumbai as its representation of Indian Kashmir deferred from Indian official maps and gave some contested territory in the northern part of this disputed area to Pakistan. Its aim had been just the opposite of creating division. The title of the work reads ‘h’ + ‘m’ = ‘hum,’ in which “h” is the first letter of the word “Hindu” and “m” the first letter of the word “Muslim.” When joined, these two letters make the word “hum” which, in Urdu, means “we” or “us” and also “same.” See Atteqa Iftikhar Ali. “Impassioned Play; Social Commentary and Formal Experimentation in Contemporary Pakistani Art.” PhD diss., University of Austin, 2008, 173. ↩

- Angana Chatterji, Parvez Imroz, Gautam Navlakha, Zahir-Ud-Din, Mihir Desai, and Khurram Parvez. Buried Evidence: Unknown, Unmarked, and Mass Graves in Indian-administered Kashmir. Srinagar: IPTK, 2009. Accessible online at http://www.kashmirprocess.org/reports/graves/BuriedEvidenceKashmir.pdf. Accessed May 5, 2017. ↩

- Skype interview with the author, July 10, 2015. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Yin Ho. “Embedded Structures: An Interview with Shilpa Gupta,” Rhizome June 20, 2012. Accessed May 5, 2017. http://rhizome.org/editorial/2012/jun/20/interview-shilpa-gupta/. ↩

- Skype interview with the author. ↩

- After Midnight, Indian Modernism to Contemporary India 1947/1997, curated by Dr. Arshiya Lokhandwala at the Queens Museum, March 8 – September 13, 2015. ↩

- Yet, according to the artist, many observers did sign up and took a slab. Interview with the artist, Mumbai, April 8, 2016. ↩

- Citizen Artist: forms of address, curated by Geeta Kapur at Chemould Art Gallery, October 14-November 15, 2013. ↩

- Skype interview with the author. ↩

- The Mazar-e-Shuhada cemetery was created in 1947 to celebrate the Kashmiris who had fought against the rule of Maharaja Hari Singh of the Dogra dynasty in 1931. It is a historical symbol of Kashmir’s fight for a self (democratic) rule and of the aspiration of a reunion of the whole valley in one single state. The creation of the cemetery was a highly political gesture associated with the return of this kingdom to the newly founded Indian Republic, instead of being seized by Pakistan. It is an official cemetery attended annually by the Chief Minister of the State on July 13th, the day of mourning for a free, democratic Kashmir. Since the 1990s, militant fighting for independence (or autonomy) from India, who died in the hands of the Indian Army, are still buried there. ↩

- Skype interview with the author. The escalating violence in the area in August and October 2016 makes such a statement politically sensible. ↩

- The “Parable of the wilderness of life” of the Mahabharata, the great epic poem related to the discovery of the divine truth, tells of the meandering of a Brahman within a deep forest where he is lured to believe that the monsters he sees are real, only to realize that they are the allegories of his own passions. See Julian Woods, Destiny and Human Initiative in the Mahabharata. Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 2001, 121. Regarding Indian classical music see Geetha Ravikumar, The Concept and Evolution of Raga in Hindustani and Karnatic Music. Mumbai: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, 2002. ↩

- Ho, “Embedded Structures.” ↩

- The exhibition, funded by the Indian Gujral Foundation, was hosted at Palazzo Benson as a collateral events of the Biennale, May 5-October 1, 2015. The exhibition, funded by the Indian Gujral Foundation and hosted at Palazzo Benson during the Biennale, presented Gupta’s works together with works by Pakistani artist Rashid Rana in an attempt to give a simultaneous visibility to two countries deprived of a national pavilion, and sharing a common history. See the foundation website for a press release and trailer of the exhibition, online access http://gujralfoundation.org/my-east-is-your-west/. Accessed May 5, 2017. ↩

- There are 106 Indian enclaves and 92 Bangladeshi enclaves. Most of them are clearly either Indian and Bangladeshi their population, a few are mixed and there is an Indian enclave in a Bangladeshi enclave owned by a Bangladeshi. According to a 2010 census, these enclaves are inhabited by around 80,000 people. In 1974, after the Indo-Pakistani war, the governments signed an exchange agreement that was never implemented. It became law in May 2015 and application decrees were signed on June 6, 2015. See Reece Jones, “Sovereignty and Statelessness in the Border Enclaves of India and Bangladesh,” Political Geography 28 (August 6, 2009): 373-381. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2009.09.006. ↩

- Skype interview with the author. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Interview with the author in the artist’s studio, Mumbai, April 8, 2016. Gupta says that contrary to her classmates who were interested in figurative art, she was drawn to Conceptual art, and later discovered with awe the works of Joseph Kosuth, Yoko Ono, Lawrence Weiner ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Nathalie Depraz, “The Phenomenological Reduction as Praxis.” The View from Within, Journal of Consciousness Studies 6 (1999): 99-100. ↩

- For the link between secret and public rhythm, see Henri Lefevbre, Rhythm Analysis, Space, Time and Everyday Life. Translated by S. Elden and G. Moore. New York: Continuum, 2004, 18. Lefevbre underpins the link achieved by rhythm between the public, the rational measure of time and the private, organic rhythm of the body. ↩

- Skype interview with the author. ↩

- Cited by Carl Ginsburg, “Body-Image, Movement and Consciousness: Examples from a Somatic Practice in the Feldenkrais Method.” The View from Within, Journal of Consciousness Studies 6 (1999): 82. ↩

- Peter Weibel, “The media of absence: Peter Weibel in conversation with Shilpa Gupta,” in Shilpa Gupta, edited by Nancy Adajania, 19. New Delhi: Vadehra Art Gallery with Vadehra Art Gallery, 2009, 19. ↩

- Yoko Ono, Grapefruit: A Book of Instructions and Drawings by Yoko Ono. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000. ↩

- Interview with the artist, Mumbai, April 8, 2016. ↩

- Cited in French from Sigmund Freud, “Le début du traitement”, La technique psychanalytique [1913 (Paris: P.U.F., 1977), 94, cited by Jean-Jacques Barreau, “Le train et les chemins du transfert,” Topique, 86 (2004) 117-136. www.cairn.info/revue-topique-2004-1-page-117.htm., DOI: 10.3917/top.086.0117. ↩

- Skype interview with the author. ↩

- Louis Althusser, Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses. Translated by Ben Brewster, transcripted by Andy Blunden. Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays, Monthly Review Press, 1971. https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/althusser/1970/ideology.htm. Accessed May 5, 2017. ↩

- Leslie White, The Evolution of Culture: The Development of Civilization to the Fall of Rome. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1959, 38-9. ↩

- Irit Rogoff, Terra Infirma: Geography’s Visual Culture. London: Routledge, 2000. ↩

- Hammar Nasar, “An interview with Irit Rogoff”, 107. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Irit Rogoff, “’Smuggling’ – An Embodied Criticality,“ European Institute for Progressive Cultural Policies (August 2006). http://eipcp.net/transversal/0806/rogoff1/en and http://transform.eipcp.net. Accessed May 5, 2017. ↩

- “‘Smuggling’ exists in precisely such an illegitimate relation to a main event or a dominant economy without being in conflict with it and without producing a direct critical response to it.” From Irit Rogoff, “Smuggling,” 5. ↩

- Hammar Nasar, “An interview with Irit Rogoff”, 102. ↩

- Ibid., 107. ↩

- Ann Huber-Sigwart, “Bridging the Gap: the work of Shilpa Gupta; Ann Huber-Sigwart interviews Shilpa Gupta”, N. Paradoxa 21 (2008), 16. ↩

- Ibid., 13-5. ↩

- Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space. Translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith. Oxford: Blackwell, 1991, 9-12. ↩

- Stefan Kipfer, “How Lefebvre urbanized Gramsci,” in Space, Difference, Everyday Life: Reading Henri Lefebvre. Edited by Kanishka Goonewardena, Stefan Kipfer, Richard Milgrom, Christian Schmid. New York: Routledge, 2008, 199. ↩

- Henri Lefebvre, The Critique of Everyday Life, Volume 1. Translated by John Moore. London: Verso, 1991, 32. ↩

- “A keener awareness of everyday life will replace the myths of ‘thought’ and ‘sincerity’ – and deliberate, proven ‘lies’ – with the richer, more complex idea of thought-action. Since words and gestures produce direct results, they must be harnessed not to pure ‘internal consciousness’ but to consciousness in movement, active, directed towards specific goals,” Lefevbre, The Critique of Everyday Life, 135. ↩

- Lefevbre, Rhythmanalysis, 18-22. ↩

- Weibel, “The media of absence: Peter Weibel in conversation with Shilpa Gupta,” 19. ↩

- Ibid., 25. ↩

- Skype interview with the author. ↩

- For a presentation of Amar Kanwar see Christine Vial Kayser, “Making Sense of the Works of Amar Kanwar: A Phenomenological Perspective.” Open Library of Humanities 2 (2016): 1–29. Accessed May 5, 2017. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.16995/olh.65. For Anshuman Dasgupta’s curatorial work see Anshuman Dasgupta, “In Unfamiliar Terrain: Preliminary Notes Towards Site-Relationality and the Curatorial,” in The Curatorial: A Philosophy of Curating. Edited by Jean-Paul Martinon, 173-182. London: Bloomsbury, 2013. ↩

- Artist’s website, http://www.shilpagupta.com/pages/2010/10speakingwall.htm. ↩

- Artist’s website, http://shilpagupta.com/library/press/speakingwall.htm. ↩

- As shown in Amar Kanwar’s film A Season Outside, 1997. ↩

- Skype interview with the author. ↩

- Lefevbre, Rhythmanalysis, 20. ↩

- Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life. Translated by Steven Rendall. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984, 117. ↩

- Ibid.97-99 ↩

- Ibid. 120 ↩

- Ibid. 120 ↩

- Ibid. 99. ↩

- Ibid., 124. ↩

- Ibid., 125. ↩

- Skype interview with the author. ↩

- Le Corbusier à Chandigarh: entre ombre et lumière. Edited by Christine Vial Kayser. Louveciennes: Musée-Promenade, 2013. Exhbiition catalog. ↩

- Tony Campbell, “Portolan charts from the late thirteenth century to 1500.” In The History of Cartography, edited by J. B. Harley and David Woodward, 371-463. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987, 389. ↩

- Skype interview with the author. ↩

- The performer was, in fact, an Italian man of Sri Lankan origin. During a second exhibition at Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, the performer was a local, darked hair woman. ↩

- Email exchange with the artist, September 20, 2016. ↩

- Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, 97. ↩

- Ibid., 108. ↩

- Skype interview with the author. ↩

- Certeau writes, “The book is dedicated to ‘the ordinary man. To a common hero, a ubiquitous character, walking in countless thousands on the streets,’ Ibid., v.; “Many everyday practices (talking, reading, moving about, shopping, cooking, etc.) are tactical in character. And so are [… victories of the ‘weak’ over the ‘strong’ (whether the strength be that of powerful people or the violence of things or of an imposed order, etc.).” Ibid., xix. ↩

- Reference to Ernst Cassirer’s concept of the relationship between word and tool as creating subjectivity might also be relevant to this analysis. See Ernst Cassirer, Form and Technology (2012), English translation by Wilson McClelland Dunlavey and John Michael Krois of Kunst und Technik, edited by Leo Kestenberg. Berlin: Wegweiser, 1930, 15–6. ↩

- Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, xviii. See also “the chorus of idle footsteps,” Ibid., 97. ↩

- Lefevbre, Rhythmanalysis, 15. ↩

- See Yuedi Liu and Carter Curtis, Aesthetics of Everyday Life: East and West. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholar Publishing, 2014. ↩