September 2 – October 3, 2020

35 E 67th Street

Written by Peter Murphy, University of Rochester

Stepping into Petzel Gallery on the Upper East Side, I felt beside myself. Months had passed since I last visited a gallery; would I remember how to behave amongst Nicola Tyson’s wondrous paintings? Fortunately, Tyson seems to be a kindred spirit for those unsure of themselves. She states in the press release that that her “center of gravity had shifted” during the pandemic. Tyson started a series of new paintings prior to lockdown, only to abandon them as the world came to a halt. She returned to eight canvases this past summer and found that “what had begun as an exploration of relationship to another, refocused instead on relationship with self.” This turn toward the self is standard for Tyson—her oeuvre is filled with vibrant and exaggerated self-portraits in which she is identifiable by her familiar auburn hair. What is not standard, of course, is the current state of the world and our presence within it. With this exhibition, Tyson asks how our sense of self changes amidst a global crisis.

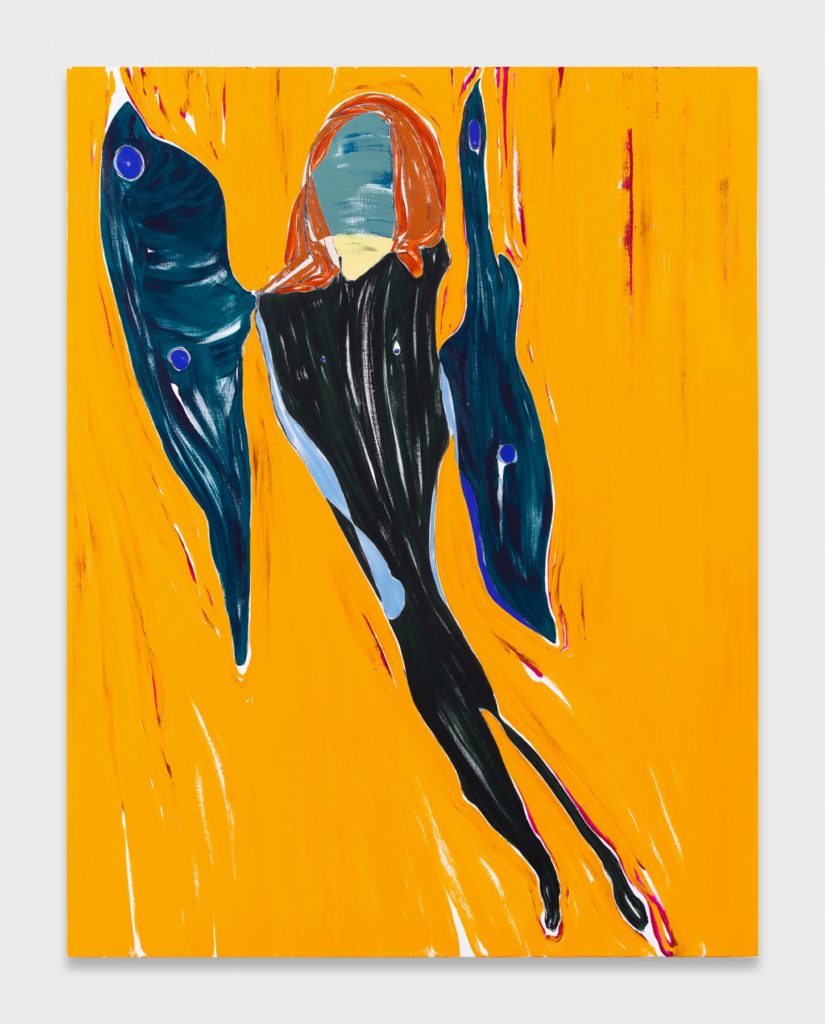

Perhaps due to the seriousness of the pandemic, Tyson continues her don’t-take-yourself-seriously approach and uses humor to address her subjects. A remarkable way in which she does this is through the construction of space surrounding the figures. In Self Portrait: Wings, for example, we find the artist as an insectoid creature. Although the wings point the figure toward the top left corner, the orange space, crimson lines, and strands of white canvas create an impenetrable surrounding. We find the figure in media res, encased in amber. Is this stasis not apropos of how we experience our lives as the world comes to a sudden halt? The self-deprecating sense of failure is precisely the point here. Humor lies in the uncomfortable, claustrophobic position the figure is entrapped in: surely anyone who had plans, ideas, or even a basic schedule prior to lockdown could relate to this struggling creature. It’s a spectacular moment for Tyson to capture, made funny and endearing by details like the royal blue circles that form her nipples and make up the details of her wings.

This sense of being trapped in weighted space appears in several of the exhibited canvases. It is often created by the vertical application of acrylic paint. Not only does this emphasize the flat, inert nature of the picture plane; it also eradicates the conventional dichotomy between figure and ground. The figures don’t appear so much against a ground as enclosed by it. In Big Yellow Self-Portrait, a lime-colored plane composed of vertical brushstrokes hugs the mostly yellow figure. Similarly, in Self-Portrait: Stripes, the stripes of the artist’s outfit echo the upward and downward blue stripes that form the surrounding area. The verticality of the stripes both inside and outside the figure weighs her down, suggesting that movement was thought possible only to discover that it isn’t.

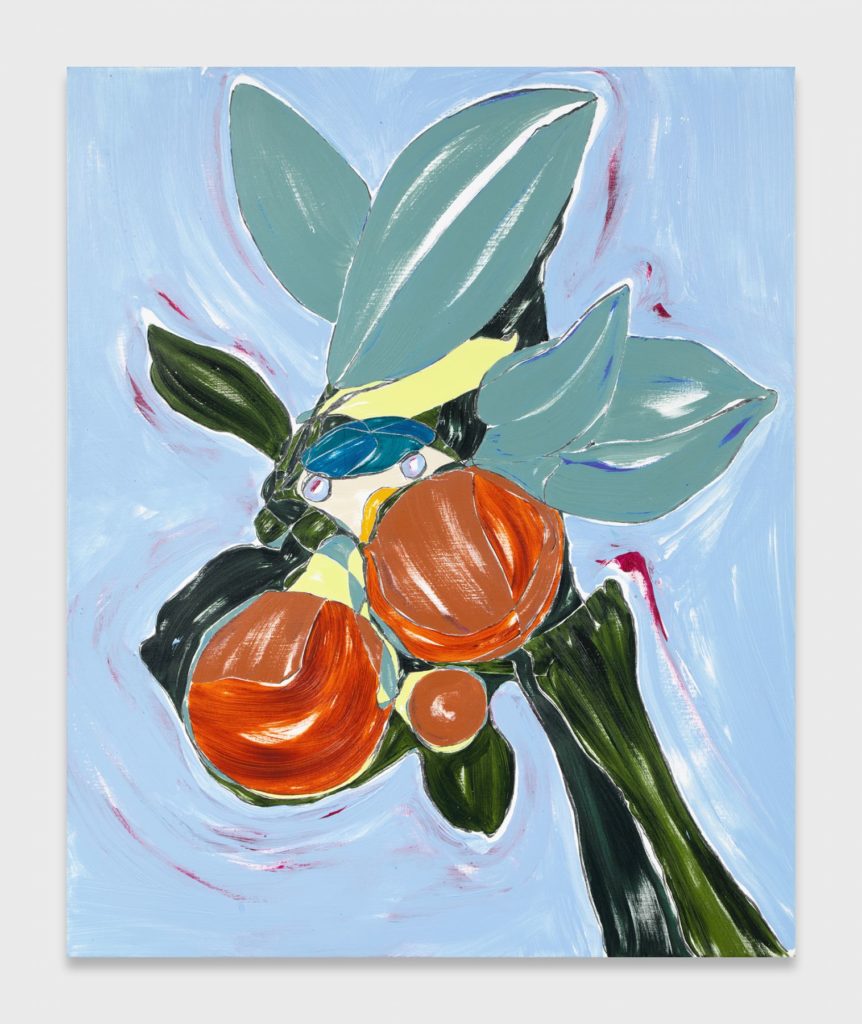

It is no coincidence that verticality, frontality, and a mixture of figuration and abstraction are present throughout these works since Tyson regularly skews these modernist tropes. Take her playful and exquisite reconfigurations of the still life. This genre uses various motifs and symbols to evoke the passing of time, but here that is complicated by the presence of bodily features. Smaller than the portraits, these four works include bulbous and elongated shapes that come together to form the titular bouquet. And yet, something about them is off: we can see leaves, but are those breasts, testicles, and faces within the bunch? Or are we imagining things? In Bouquet 1, two nearly symmetrical circles in shades of reddish-orange starkly contrast the blues and greens that cover the canvas. Although fruit might be unexpected in a bouquet, one is hard pressed not to see these circles as oranges. Tyson knows that fruits have been used throughout the history of painting to evoke the female body, but these oranges may be representative of breasts rather than an evocation of sexuality. This is by no means a reclamation or repetition of modernism’s lustful fruits; it is an engagement with the female body by a lesbian artist who could find the depiction of breasts to be both titillating and something to identify with. Regarding the appearance of seemingly random breasts throughout her work, Tyson states, “You know, that’s what I know. So I draw that.” But rather than let the viewer consume this sexual fruit freely, a face appears in the center of the bouquet (the artist’s?) cheekily gazing back at us.

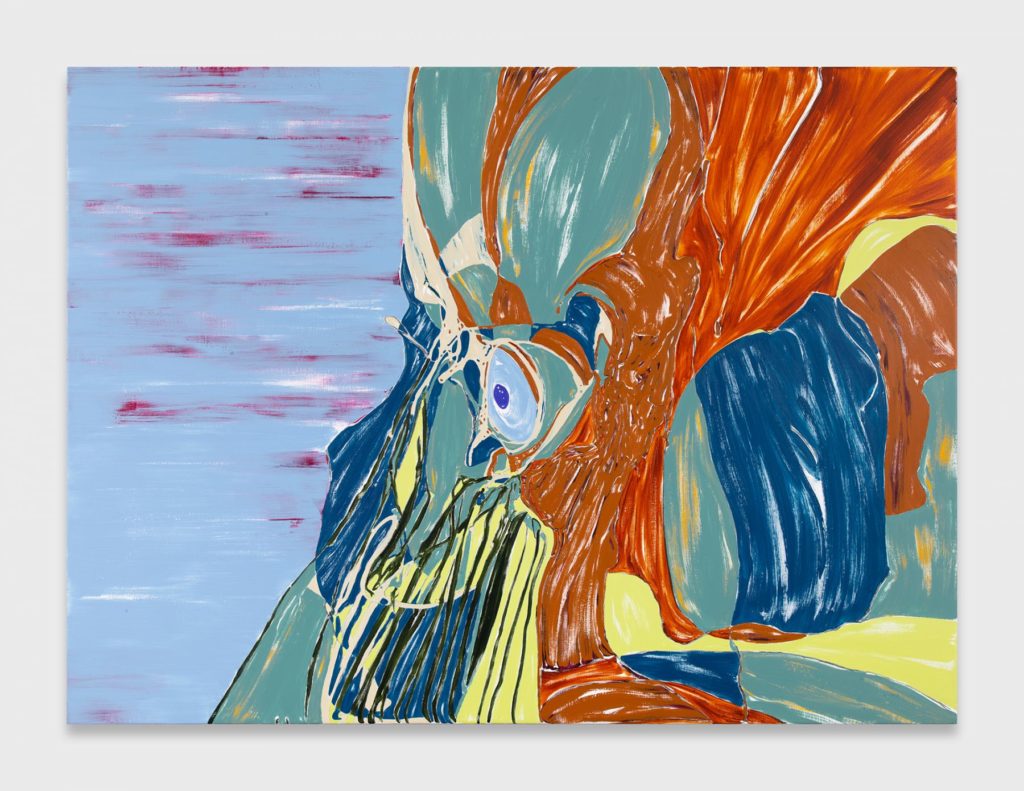

The playfulness and complexities present in the self-portraits and still lifes culminate in the magnificent Don’t Look Back. A flurry of colorful shapes comes together into a large mass that occupies two-thirds of the canvas. The remaining third is dominated by horizontal strokes of light blue, with crimson and the white of the canvas peering through in slivers. The horizontal lines are imbued with the suggestion of movement found in the other self-portraits, but here something else is happening: a face is breaking through the left side of the collected shapes. The breast-like eye (or eye-like breast) manically stares toward the more open space, seemingly shattering the other forms that hold the face in place. Once again Tyson draws us into an uncanny situation: who wouldn’t furiously break through what weighs us down to get to something lighter, even just to get away from ourselves? When viewing the face breaking toward the blue plane, it’s tempting to think “the sky’s the limit,” but Tyson is far too clever for an easy cliché. If there’s any limit, it is the selves we inhabit. Truth be told, I was already unsure of myself prior to the pandemic. But if my center of gravity has shifted like Tyson’s, maybe this is my chance to not think about up and down but rather forward and back. If that’s the case, Don’t Look Back isn’t just a title—it’s an invitation.

1 Comment