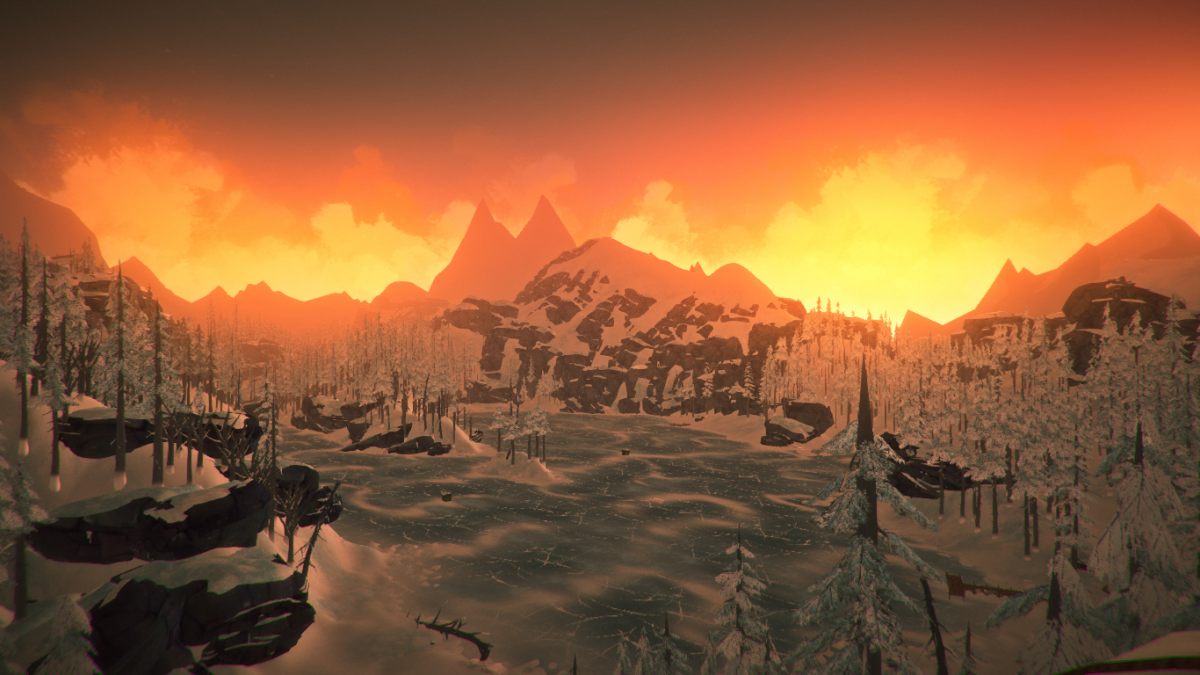

Set on a remote island on the northwest coast of Canada, The Long Dark is a survival-exploration video game that offers an ostensibly regional vision of an otherwise global apocalypse. The player confronts the aftermath of a mysterious geomagnetic event that has rendered most modern technology inoperative and effected an extreme shift in climate. The essential task is to navigate a desolate rural environment without succumbing to starvation, cold weather or aggressive wildlife.1 Since its initial release in 2014 the game has gained a devoted following of players who prize its open-ended gameplay, permanent death system, and immersive atmosphere.2 Indeed, in response to a public survey question of “What is the 1 thing you enjoy most about The Long Dark?” one poster on the developer’s forums replied: “It’s like being in a group of seven painting, the artwork is fabulous…”3 Although expressed here with a heightened degree of specificity, the general sentiment speaks to a key aspect of The Long Dark’s appeal. Played in first person, the game employs a minimal HUD (Heads Up Display) and unobtrusive interface system in order to maximize the user’s direct interaction with a virtual space that is designed for aesthetic appreciation. The art style is relatively abstract, simplifying the details of objects and stylizing their shapes in order to create a cohesive world that is further enlivened by a host of dynamic weather and lighting effects. A bright and vibrant colour palette is used throughout. This visual presentation is further aided by map designs that deploy topographical features in a way that affords a highly pictorial experience, whether by using trees and hills to frame views of larger areas or including accessible, elevated vantage points from which one can survey their surroundings.

The Long Dark (Screenshot). Credit: Baukster77 on www.hinterlandforums.com

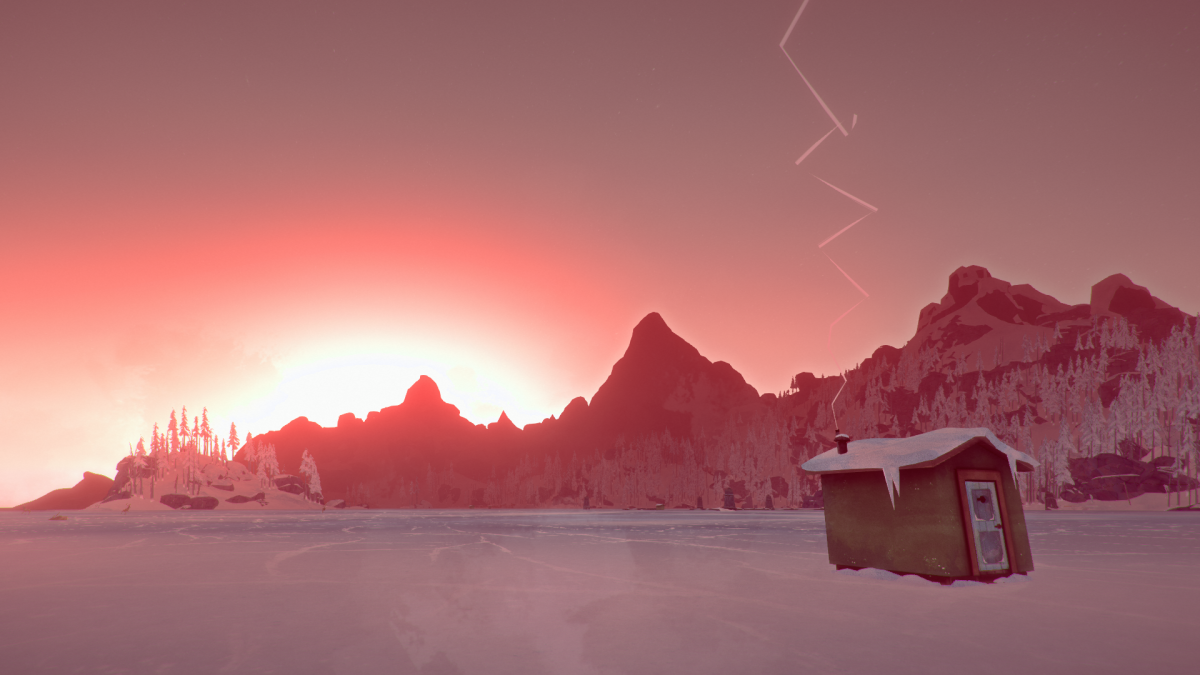

But for all its beauty the player who moves through this world is never far from death’s door as they are constantly reminded of its fundamentally inhospitable nature by the freezing temperatures and scarcity of resources. The resulting experience fluctuates curiously between a sense of urgency inspired by the imperative of securing food and shelter, and a detached appreciation of particularly striking arrangements of scenery: the sweeping vista that appears upon cresting a hill or emerging from the forest suddenly occupies one’s senses and eclipses the objective of a given expedition; a breathtaking sunrise briefly offsets the prospect of a stockpile-depleting, week-long storm. The contemplative aestheticism that thus punctuates the salience of The Long Dark’s goal-oriented gameplay replaces action with stillness, immediacy with distance.4 Exposing the viewer to an overwhelmingly vast and ultimately indifferent landscape, it is a sublime beauty that visually recapitulates the game’s apocalyptic logic.5 The Long Dark depicts the end of civilization, if not humanity: faced with inevitable death, the player’s powerlessness before their fate is articulated by the contrast between their tenuous individual position and the enduring, immutable space of their surroundings. During these moments of apprehension they are separated from the environment by their interpolation as a viewer (insofar as these moments depend upon the player’s ideal placement in time and space so as to observe eye-catching optical phenomena).

The Long Dark (Screenshot). Credit: Warsaw on www.hinterlandforums.com

In this sense the game’s likening to a group of seven painting is apt: reviving the romanticizing trope of landscape in the same way as the latter, it takes part in a tradition of sublime representations of a notional nature from which human agency is fundamentally distinguished.6 But it is even more appropriate as a formal, rather than thematic, comparison: the relationship that The Long Dark’s interfaces and graphics facilitate between the player and the world is, of course, a mediated one—putting them in contact not with the environment but its representation. This is exactly like “being in a painting.” The player engages with a preprogrammed model of the world whose primary condition of possibility is the foreclosure of radical change.7 Its appearance is premised on the absence of any human intervention beyond that which occasioned its creation in the first place.8 That said, unlike in the tradition of Western landscape painting, this absence does not refer to a metaphysical division between nature and culture that makes the former the object of the latter’s prospective self-realization via the mediation of concepts. Rather, it is the speculative absence of any such future viewer, a reflection on the limits of human imagination that gives us a fixed vision of climate change as a zero-sum game.9 The paradox of a human conception of a human-less space reveals the self-destructive form of apocalypse that is operative in The Long Dark. The overwhelming force of the sublime is in this case less natural than historical. Its source is eminently cultural: painting as an abstracting engine of representation. From the perspective of the present in which The Long Dark was made, the romanticized image of the landscape appears almost malign due to the environmentally damaging technological encroachments that its conjuration of an untapped pristine wilderness replete with endless natural resources has historically authorized.10 The specific motifs of this sublime are, accordingly, less the purportedly ‘natural’ features of the landscape than their catastrophic interaction with human infrastructure and settlement: rockslides that have buried roads and tunnels, the burned-down, snow-choked shells of houses, defunct factories from boom-bust resource industries, and trains derailed by warped railroad tracks.

The Long Dark (Screenshot). Credit: Sharky on www.hinterlandforums.com

The Long Dark’s regional vision of worldwide apocalypse can thus be read in terms of the totalizing entrainments of economic globalization and human-caused climate change. This fraught relationship between the local and global certainly bears upon the place and time of the game’s making. The province of British Columbia where it is set is also where the developer’s studio is based. For the last few decades, moreover, the province has been wracked by debates over economic development projects that propose to route oil and natural gas from inland Canada to tanker ports on the coast. Environmentalist opposition to these projects has employed a similar logic to The Long Dark in their representation of a British Columbian landscape whose beauty is negatively defined by the possibility of its total destruction. The 2012 exhibition “Canada’s Raincoast at Risk: Art for an Oil-Free Coast,” for example, was comprised of works by over fifty artists whose depictions of otherwise “natural” scenery were taken as the imperiled stakes of a looming decision to allow increased oil tanker activity on the coast. As Beth Carruthers writes in the afterword to the exhibition catalogue, “The threat represented by dozens of VLCCs (very large crude carriers), each carrying some 227,000 dead weight tonnes of diluted bitumen through these wild and dangerous winding waterways, and the inevitable consequences of doing so, provides a terrifying vision.”11 The dangerous technological processes at issue here evoke a similarly dangerous vision of the environment in which they will intervene—the coastal waters of BC become ‘wild and dangerous winding waterways’ only from the perspective of this risk-prone enterprise. Its awe-inspiring magnitude and danger is thereby projected onto the landscape as a property of the latter’s representation.12

Chili Thom, What Lies Beneath. (Exhibited in “Art for an Oil Free Coast”) Acrylic on canvas, 2012.

- The game features a linear, narrative-driven “story mode” (released in 2017) as well as a sandbox style “survival mode” (released in 2014 with the game’s initial launch on Steam Open Access) where the player is free to explore the world. The latter has proved overwhelmingly popular amongst the game’s early adopters. ↩

- The Long Dark automatically saves a player’s game whenever they enter or exit a building, go to sleep, or suffer an injury. While this allows the player to resume an ongoing game session, if their character dies the save file is deleted and they must restart the game from the beginning. ↩

- The comment was posted on January 31, 2018, by the user Cr41g. The Group of Seven was a group of Canadian landscape painters active between 1920 and 1933, and consisted of Franklin Carmichael, Lawren Harris, A.Y. Jackson, Frank Johnston, Arthur Lismer, J.E.H. MacDonald, and Frederick Varley. They are known for collectively pioneering a distinctly “Canadian” school of art characterized by colorful and frequently impressionistic representations of the Canadian landscape. ↩

- As distinct forms of perception, these subjective attitudes correspond to the different modes of engagement described by the terms “survival-exploration” (the official terms used by the developer of The Long Dark in describing the game). Survival is an abstract activity with concrete significance, confined to interfaces and interiors as the player monitors their physical condition, manages items in their inventory and shelters from inclement weather. Exploration is visual and detached, as one takes in long distances, scopes out predators and resources from afar, and apprehends the natural ‘facts’ of the landscape. ↩

- Not only do these aesthetic moments reveal the diminutiveness of the player’s character in comparison to the inhospitable world in which they are placed, but they also highlight the character’s transience relative to this environment. (Because it is the setting of the game that persists, for the human player, between the frequent experience of their character’s death.) ↩

- With its insistent references to a Canadian identity in the objects that fill the world and denote a certain proximity to the outdoors, The Long Dark can also be seen to nationalize nature in a way akin to the group of seven’s attempt to represent the Canadian north in cultural terms (i.e. via a school of painting). ↩

- I.e. of deviation from its initial parameters. ↩

- Whether by creating the video game itself, or by creating the global-environmental state of affairs that has fallen into an irreversible disaster. ↩

- This is to say that The Long Dark’s vision of the environment is homologous with that of an understanding of climate change as a global crisis whose extreme consequences (the end of the environment’s ability to sustain human life) demand an equally extreme response on the part of human civilization (insofar as its very survival is at stake). The increasingly cold and inhospitable landscape of the game (wherein the player’s best efforts only serve to postpone their inevitable death) can be read as a depiction of a moment in which it is now too late—in other words, of a moment in which human agency has lost its ability to decisively shape the future course of the environment on earth. For a discussion of human agency and the crisis of climate change, see Dipesh Chakrabarty, “The Climate of History: Four Theses,” Critical Inquiry 35 (Winter 2009): 197-222. ↩

- See Peter White, “Out of the Woods,” in John O’Brian & Peter White, eds. Beyond Wilderness: The Group of Seven, Canadian Identity, and Contemporary Art (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2007), and David Rossiter, “The nature of protest: constructing the spaces of British Columbia’s rainforests,” Cultural Geographies 11 (2004): 139-164. ↩

- Beth Carruthers, “Cartographies sans bornes: Maps without Borders,” in Canada’s Raincoast at Risk: Art for an Oil-Free Coast (Altona: Raincoast Conservation Foundation, 2012), 148. ↩

- Carruthers identifies this sense of risk as the impetus for the images in the exhibition when she adds that “One of the best responses to terrifying visions is the power of art.” In a significant way, then, the “nature” accessed by the art in the exhibit is not just any nature, but nature seen from the perspective of the processes it opposes. Carruthers, “Cartographies sans bornes,” 148. ↩