Issue 19: Blind Spots (Fall 2013)

Invisible: Art About the Unseen 1957-2012. London, Hayward Gallery. 12 June – 5 August 2012 / Gallery of Lost Art, an online exhibition curated by Tate. 2 July 2012 – 2 July 2013.

Invisible: Art About the Unseen 1957-2012 is a unique attempt to consider the meaning of “how to look at art.” The show, comprised of invisible artworks by twenty-six artists, foregrounds a notion that so-called invisible art has little to do with identifying the invisible with the ontologically absent. Its interest lies rather in the way to suspend ‘visibility’ as the most predominant condition for the production and appreciation of works of art. Granted, viewers still found some amount of the visible in the gallery space despite the presumable emptiness suggested by the exhibition’s title. Nonetheless, most of the presentations in the show recounted the absence of conventional art as a tangible object, particularly artworks that documented things and events no longer available or showed only themselves as empty containers rather than explicit content – white walls, frames, pedestals, blank papers, etc. Following the show’s organizational ethos, invisible art creates, then, an experimental site with a mixture of hope and concern about what emerges by rendering something invisible.

In his essay for the exhibition catalogue, Hayward Gallery Directer Ralph Rugoff writes: “[the exhibition] brings together key moments and agendas that have led artists to engage the invisible, the unseen, and the hidden.”1 However, measuring invisible artworks through these indistinguishable concepts is difficult. Understanding issues posed by the works provide a framework to discuss their mutual significance and interrelation. These issues surface mainly through making what has been visible invisible and making what is often invisible (or unseeable) perceptible. Yves Klein’s 1957 exhibition at the Galerie Colette Allendy simultaneously pursued both practices. It consisted of unpopulated white walls (the absence of visible art) and their infusion with “the pictorial sensibility in the raw state” (the presence of the unseen); hence Rugoff positions Klein as a progenitor of invisible art.2 Regarding Klein’s presentation of the concept of ‘invisible’ as a point of departure, Invisible traces a rich history of invisible art from the late 1950s to the present by focusing on works, including those mentioned in what follows, that ‘invisualize’ crucial elements – artist, object, medium – in conventional art making.

Works by James Lee Byars (1932-1997) and Chris Burden (1946- ) included in Invisible engage the idea of the invisible or disappeared artist. Byars’s The Ghost of James Lee Byars (1969/1986) is an empty room full of darkness, representing the impossibility of doing anything but being haunted by the specter of the artist. In White Light/White Heat (1975) performed at Ronald Feldman Fine Arts in New York, Burden played an invisible artist by remaining on an elevated platform in the gallery for twenty-two days; while offering nothing seeable, these works attend to the invisible presence of the artist as well as the space and time surrounding them, perhaps even increasing their proprioceptive capacities.3

A withdrawal from presenting art as a tangible object is a common thread that runs through projects by Yoko Ono (1933- ), Terry Atkinson (1939- ), Michael Baldwin (1945- ), and Tehching Hsieh (1950- ) included in Invisible. Ono’s Hand Piece (1961) makes viewers primary producers; the piece offers only instructions typed on a sheet of paper and its manifestation is completely dependent on viewers’ arbitrary enactions. In 1972, Atkinson and Baldwin, founding members of the conceptual art group Art & Language, first presented The Air-Conditioning Show at the Visual Arts Gallery in New York. The exhibition consisted of an empty air-conditioned room in which a temperature was kept moderate to emphasize the “abnormal normality”4 of the show. Similar to Ono’s Hand Piece, The Air-Conditioning Show included ‘nothing’ but a series of lengthy assertions concerning the condition of artistic production, suggesting that (reading) texts could also comprise the realization and experience of an artwork. In contrast, Hsieh’s self-repressive performance work is a case of making or exhibiting ‘no’ art. In one of his One Year Performances (1985-1986), Hsieh stopped making, speaking, reading, and seeing art for one year; in Tehching Hsieh 1986-1999, he refrained from publicly showing what he had produced during the thirteen-year period.

Magic Ink (1989) by Gianni Motti (1958- ) is a drawing made with invisible ink whose images vanish from the very moment they are drawn. For Motti telepathy is another invisible medium, and in Nada por la fuerza, todo con la mente (1997) he used it to contact and persuade the then Colombian president Ernesto Samper to resign in atonement for the country’s social unrest. In turn, a drawing material Song Dong (1966- ) uses to write in his diary is water in order to impregnate his inner self with a hard stone: “Although it is just a stone, it has become thicker day by day, with my own thoughts added on it.”5 Photographs documenting Dong’s practice of writing show the process of meditative absorption rather than mere evaporation, just as invisible paintings by Bruno Jakob (1954- ) create latent images by representing immaterial energies such as light, air, and brainwaves.

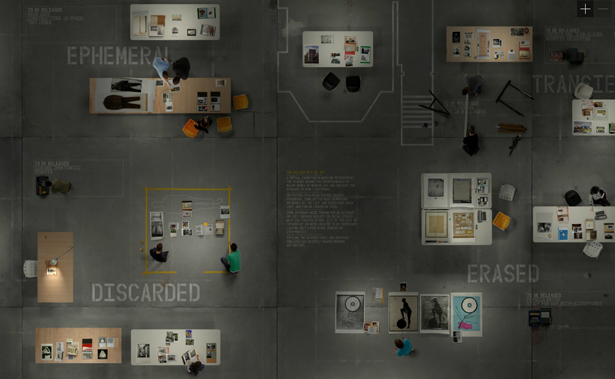

With the above and other invisible art works, Invisible ably demonstrates the critical importance of exploring “the actuality of art”6 through various invisible processes. Meanwhile, it seems less able to attend to the fact that artworks can also be rendered invisible outside artistic creation. As a possible corrective, art that has repeatedly experienced forced disappearance under violence inspired another exhibition of invisible art launched in July 2012. Gallery of Lost Art, a yearlong virtual exhibition curated by Tate, “tells the stories of artworks that have disappeared. Destroyed, stolen, discarded, rejected, erased, ephemeral—some of the most significant artworks of the last 100 years have been lost and can no longer be seen.”7 When invisible art matters, one may think not only of how to look at art, but also of the unsettling reality of the conditions that make art invisible. Art can be made invisible or ‘non-existent’ by irrational behaviors, and even its potential storytellers can become vulnerable to terror, war, and political oppression. As such, Tate’s virtual exhibition does not position invisible art as an interrogation of conventional artistic practices dedicated to the production of ‘visible’ objects per se; rather its fundamental proposition is quite opposite to that of Invisible. Gallery of Lost Art centers on the profound creativity of being invisible, the survival of art and resistance against its undesirable disappearance.8

- Ralph Rugoff, “How to Look at Invisible Art,” Invisible: Art about the Unseen 1957-2012 (London: Hayward Publishing, 2012): 5; emphasis added. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- See Kristine Stiles, “Burden of Light,” Chris Burden (London: Thames & Hudson, 2007): 24. ↩

- “Art & Language,” Invisible, 39. ↩

- Quoted in “Song Dong,” Invisible, 63. ↩

- Rugoff, “Invisible Art,” 27. ↩

- “The Project,” http://galleryoflostart.com/ (accessed on 26 July 2013). ↩

- Incidentally, Lost Art was “live for 12 months before being lost itself.” For remnants, see http://galleryoflostart.com/. ↩