Written by John Roberts

I. Introduction

In a dimly lit home office, a writer gets to work: taking notes while screening home movies and hoping (needing desperately, in fact) to make sense of the footage somehow, to scrutinize the screen until it yields a meaningful, self-evident explanation of its visual contents. The writer is Ellison Oswalt, protagonist of Sinister (Derrickson, 2012), but this description, with slight modifications, could just as easily fit the (post-)cinematic spectator of Paranormal Activity (Peli, 2007), who examines that film’s home movies with the same level of investigatory intensity, and with similar outcomes: both will be fascinated and frightened by the images they see, and also be made palpably anxious by the evidentiary truths those images do and do not disclose. Shifting frames again, the description could apply as well to the spectator of Sinister (academic or otherwise), engaging in processes of narrative hypothesis-testing and thematic construction: a forensic construction of narrative that pieces together coherent meaning from a flow of audiovisual data in time.

This essay explores how Sinister, in its incorporation of processes of forensic spectatorship within the film’s narrative diegesis, stages a pair of dialectically interrelated cultural and technological oppositions: on the one hand, the film figures Ellison’s activity of spectatorship and forensic reconstruction narratively as a form of precarious labor that is necessary for him to support his family in a time of economic hardship, coming as it does on the heels of the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent recession. On the other hand, the film also figures this activity as a form of (de-)securitizing surveillance, the ethical and existential anxiety of which is produced through the haunted media object’s ability to reverse the flow of surveilling control from object to perceiving subject. Sinister articulates the relationship between these two forms of anxiety in regards to economic/domestic and national security respectively, which is also to say between the speculative labor of surveillance as a defense of the homeland and the creative labor of economic speculation as an act in defense of the property value of one’s home-land. Crucially, however, the film’s stages this dialectical opposition through its diegetic interrogation of the status of audiovisual media in moments of technological transition from celluloid film to digital video. This emphasis on digitization in turn provides the unifying sublation between the two forms of domestic and national speculation in Sinister, providing a new conceptual ground upon which to speculate about the state of speculation itself that extends beyond the diegetic narrative of the film to directly implicate the film’s spectator.

Since the remarkable and unlikely success of Paranormal Activity, which was produced in 2007 but did not see wide theatrical release until 2009, the American horror film genre has undergone a significant shift towards films that resemble the surprise hit both in terms of style and content. Most pointedly, the influence of Paranormal Activity has been felt through both the use of found footage aesthetics as an organizing stylistic and narrational feature, and through a renewed emphasis on narratives of supernatural possession. In particular, in addition to the six films in the Paranormal Activity franchise (2007-2015), REC (Balagueró and Plaza, 2007), Cloverfield (Reeves, 2008), Diary of the Dead (Romero, 2008), the anthology film V/H/S (2012), and Europa Report (Cordero, 2013) represent only a small sample of the horror and science fiction films that have appropriated the aesthetics of found footage video, and have done so across relatively diverse generic contexts.

Critical scholarship on this cycle of films has emphasized two significant features: on the one hand scholars have examined the appropriation of documentary aesthetics as a both compelling and problematic aspect of the cycle, insofar as the films seem to appeal to the credible veracity of documentary in order to depict incredible, supernatural occurrences. On the other hand, scholarship has also emphasized the cultural anxieties embedded in this very tension between documentary style and fantastic, supernatural content, particularly as it relates to the processes of mediation involved in producing such images. As the introduction to a recent edited collection of essays on horror cinema in the digital age attests, “digital horror is a cinema of anxiety embodying, in its ‘shaky-cam’ cinematography, verisimilitudinous mise-en-scène, paranoid narrative propensities and often startling visual imagery, a range of concerns regarding the technologically-mediated and globally capitalized subjectivity of the present.”1 Both of these analytical prongs are present in Barry Keith Grant’s article on what he terms “verité horror and sf film,” which he defines as a cycle in which “the camera exists within the diegesis, often with much of the story unfolding in real time, as if it were there recording actual not fictional events, as in the documentary tradition of cinema verité.” Grant further contends that “the realist aesthetic of these films, in combination with their fantastic and frightening elements, reveal a postmodern anxiety about the indexical truthfulness of the image that has been exacerbated by the ubiquity of digital technology.” He identifies the core anxiety in the cycle as a tension between the digital image and its ability (or lack thereof) to indexically affirm evidentiary reality, a worry which is articulated in the context of the emergence of reality television in the years after 9/11’s traumatic televised documentation.2

Caetlin Benson-Allot similarly argues, regarding what she terms as “faux footage horror,” that these films “dramatize the risks of finding media files in the twenty-first century.” She links the ‘seemingly found’ aspect of the cycle to an ethical dilemma regarding the status of pirated media images in the contemporary digital era of easy and immediate access. The documentary aesthetics of such films suggest that they have been “unethically obtained, that we are not supposed to be watching these images [emphasis in original].” Reading these films as contemporary media industry morality tales, Benson-Allot claims that the ethical crisis of spectatorship precipitated in this cycle gestures towards a cultural and industrial fear regarding media piracy and the unauthorized dissemination of digital images beyond the control and economic exploitation of the media industries.3

I want both to press these arguments further and, at the same time, bring their central claims closer together by suggesting that the ruinous consequences of the unauthorized circulation of images allegorize the unauthorized, unethical circulation of wholly digitized finance capital through global markets, before finally coming home to roost in the traumatized body itself. If Grant’s concern is about the inability of the verité image to secure the indexical real, and Benson-Allot’s is a social anxiety about unauthorized circulation, then the site where both of these concerns meet is the image as a form of financialized monetary abstraction, securely tied neither to the (commodity) body nor to appropriate regulatory oversight. As Fredric Jameson has pointed out, the global flow of capital has undergone a second process of abstraction beyond the initial abstraction necessary to produce the money-form of capital. The digitization of finance capital through globally interconnected markets enables these abstractions of the money form, as complex financial instruments, to exchange for each other without ever passing through the commodity form of Marx’s general formula for capital.4 Along somewhat similar lines, W.J.T. Mitchell has argued that the ‘reproduction’ in Walter Benjamin’s ‘age of mechanical reproduction’ has now taken on a biological meaning, in which “[r]eproduction and reproducibility mean something quite different now when the central issues of technology are no longer “mass production” of commodities or “mass reproduction” of identical images, but the reproductive processes of the biological sciences and the production of infinitely malleable, digitally animated images.”5 In this sense, then, the question of ‘authorization,’ or a lack thereof, takes on a double valence in raising a question about the efficacy of regulations and legal protections on intellectual property, but also asserting the ambiguous authorship of digital images that circulate virally in ways that echo the dizzying abstractions of wholly digitized financial instruments. In Sinister, this disjunction of figured as a kind of action at a distance, in which such images do in fact possess a supernaturally vitalistic ability to disrupt and ultimately destroy the human body.

Therefore, I want to suggest that the critical and cultural significance of this cycle of horror and science fiction films discloses substantial concerns with digital mediation and its role in culture more broadly. This, then, provides ample reason for the close study of a second cycle of horror films‒of which Sinister is one of the key constituents‒that appears to be reflecting critically on the wave of verité/faux footage horror by self-reflexively incorporating the act of spectatorship, an act previously reserved for the viewing audience, within the diegetic world of the films’ fictions. 6 In particular, Sinister, a Blumhouse production starring Ethan Hawke, directed by Scott Derrickson, and written by Derrickson and C. Robert Cargill, distinguishes itself from its antecedents by shifting narrative and stylistic emphasis away from the verité image as such, and towards the narrativized act of viewing such images, which is figured as deeply fraught by ambiguity regarding the empirical status of digital images, their authorship, and loss of control over both their circulation and value. Unlike Paranormal Activity and other similar films, in which the fraught activity of spectatorship is performed by the spectator of the film, Sinister narrativizes that anxiety diegetically. In doing so the film aptly articulates a broad cultural fear regarding the loss of home value and economic stability during the post-2008 era to a specific concern regarding the pervasiveness and effectiveness of surveillance technologies in the digital era, and in doing so is exemplary of the second cycle of verité horror. Crucially, the film renders these anxieties around the economy and surveillance commensurable through the presentation of surveillance as economic labor, and indeed as the creative labor of narrative authorship itself, anticipating the professionalization of supernatural detection in The Conjuring (Wan, 2013).

Julia Leyda has perceptively argued that the Paranormal Activity films function as “an ongoing post-cinematic allegory of debtor capitalism” in which “the digital is the link between the nightmare of debtor capitalism and the horror of the camera as non-human agent that captures the malevolent actions of the non-human demon.” She demonstrates how the franchise’s use of digital technologies and narrative concern with the haunted house allegorize and explore the post-cinematic condition of contemporary capitalism, focusing specifically on credit and debt under transnational finance capital.7 Likewise, Annie McClanahan has recently argued that contemporary gothic horror films express economic anxieties regarding post-crisis financial precarity by “explicitly link[ing] the formal trappings of horror to the context of real estate lending, mortgage speculation, and foreclosure risk.”8 While these perspectives are astute, and much the same could be argued regarding Sinister, this essay focuses more centrally on the relationship that the film constructs between images, labor, and value, as opposed to an emphasis on anxiety regarding debt obligations and risk as sources of precarity, though this is undoubtedly a crucial factor in the way the film’s narrative and affective horror is constructed. What makes Sinister distinctive is the way the film figures the articulation between concerns regarding surveillance labor and property value in terms of the ontological transition from analog 8mm film to digital video, a transition which is accompanied by an attendant loss of control over the image that occurs in the process. The way in which these media ontologies seem also to mediate between national and economic forms of speculative securitization is especially prominent in the film’s use of rhythm and texture, in both its visual and sound design. Sinister braids intertwining economic, cultural, and technological anxieties pervading the contexts of the recession, the family, and the parallel ontologies of both digital images and digitally circulating finance capital. The structure of this analysis follows the film in this respect, attempting to follow the threads and knots of historical figuration at work in the film, beginning by establishing the film’s status as a narrative of anxiety regarding imagistic and economic control.

II. Recession Anxiety, or the Haunted House

Sinister’s narrative begins with true crime writer Ellison Oswalt (Ethan Hawke) moving his wife and two children from a spacious, expensive home funded by Ellison’s book profits into a much smaller and humbler one. Unknown to Ellison’s family for most of the film, the previous occupants of the new house, the Stevenson family, were gruesomely hanged in the backyard and are the research topic for Ellison’s new book project. The film’s narrative makes it clear that Ellison is under pressure to repeat the success of his single hit book, Kentucky Blood, after a string of duds has stalled his career as an author. An early exchange of words with the local sheriff (Fred Thompson) suggests that Ellison’s recent failures may have come as a result of a failure to “get it right,” indicating that the author’s research and reconstruction of events was insufficient to produce a viable narrative either ethically or financially. In the sheriff’s words, Ellison’s “bad theory helped a killer go free. [Ellison] ruined people’s lives,” and the sheriff discourages the investigation, asserting that “you can never explain something like this,” suggesting that the Stevenson family murder is something inexplicable and best left alone. Soon after the conversation with the sheriff, Ellison explains to his daughter Ashley that they had to move into the home because Ellison could no longer afford the old one, although he holds out the possibility of moving back to their old home once the book is successful. Later on that night at the dinner table, Ellison’s wife Tracy tells the children, Ashley and Trevor, that they won’t be able to eat out in restaurants much until their old house is sold. When Trevor suggests lowering the asking price on the old home to help sell it faster, Ellison responds by claiming that they have already lowered it as much as possible and that poor market conditions are responsible for their tight budget while also noting that once his new book is written and sold, the family will be “on easy street.”

Ellison’s early conversations with the sheriff and his family not only do the necessary narrative work of characterization, but also connect together the ethical and economic pressures associated with Ellison’s forensic reconstruction and authorship of a coherent and ultimately lucrative narrative out of research data. Since the livelihood of the Oswalt family depends on Ellison’s ability to piece together the story of what happened to the Stevenson family, his investigation into what befell the Stevensons is inextricably linked to preventing his own familial dissolution, even before any overtly supernatural elements come into play in the film. Ellison’s early exchange with the sheriff allows scenes of Ellison screening home movie footage to be understood as a form of research labor inflected by an economic pressure to reproduce an economic success, with the value of such labor framed in terms of the ability to skillfully and accurately produce narrative meaning out of forensic data, and in turn to transform that narrative meaning into valuable media content. Just prior to Ellison’s first examination of the home movie footage, Tracy informs him that if this research project goes as poorly as the last one has, she will take the children to her mother’s house‒a scenario that would resemble a marital separation‒despite Tracy’s self-proclaimed motivation of removing the family from the critical scrutiny of the unfriendly community. In short, the mystery at the heart of Ellison’s investigation is as much about resolving a crisis of diminishing labor value and the disappearance of money, as it is about the murder and disappearance of human beings. For the film, these two exchangeable modes of suffering‒economic and bodily‒are intertwined and causally interconnected by Ellison’s forensic labor, labor which is itself situated as necessary to affirm and maintain the security of the nuclear family in the face of a broader undoing of the social community.

The economic imperative informing his research becomes a central motivation for Ellison in the film, keeping the Oswalt family in the haunted home even after Ellison begins to suspect he and his family are in danger. The more Ellison learns about the case, the more his family becomes increasingly endangered, while the potential profitability of his book project escalates proportionally. Ellison’s decision to place the economic prospects of the book above his family’s comfort and safety is repeatedly emphasized through the fracturing of his initially happy relationship to his family over the course of the film. Trevor’s night terrors, both children’s troubling drawings of murder victims in inappropriate locations (including on the walls of the new home), and the revelation that Ellison has lied about moving them into a crime scene contribute to the intense straining of the family relationship across the film.

The children’s “number one rule”‒not to go into their father’s office‒also establishes the site of forensic investigation and labor as a forbidden site, marked off for the working father and distanced from the rest of the family. This prohibition also figures the site and scene of surveillance labor as both invisible and inaccessible, and to the extent that Ellison’s speculative labor resonates with the speculative securitization of geopolitical surveillance, reflects the perceived immateriality and invisibility of both labor and surveillance as something that occurs either ‘over there,’ and/or ‘nowhere in particular,’ and that is performed seemingly by no-one.9

Eventually, Ellison’s research leads him to realize that he has embroiled his family in a mortally dangerous relationship to Bughuul, a Babylonian demon that resides within and haunts images of itself. The structure of Bughuul’s curse, which activates when a family moves into a home previously occupied by the curse’s previous victims, but which propagates by murdering families only after they move out of the cursed home, reinforces the film’s anxious depiction of home ownership, in which the home is formally figured as a container of traumatic possession caught up in the seemingly viral nature of declining property values. The operational logic of the curse connects the families it destroys in a network that geographically spans a wide swath of the United States and reaches temporally backward to the 1960s, when the curse began and when the economic and social fabric of conservative midcentury American society began to unravel. Much of the film’s home movie footage is drawn from the decade of the 1970s, a decade in which many American families experienced economic stagnation while American capital underwent explosively rapid transnational growth through financialization.10 In Sinister, moving out of one’s home and into a home that, as Ellison remarks, “came on the market and was a steal,” seals one’s fate as a victim of familial and, in The Oswalts’ case, existential disintegration. It is as though the trauma of having one’s home lose value, as much as the trauma of haunting and violent death, is what circulates among the interconnected families of victims, and it circulates via the mechanism of moving from one home to another. The film thereby puts an allegorical, and yet oddly literal, twist on the Heideggerian notion of the uncanny as literally “not-being-at-home” in one’s own home, haunted by the specter of “homelessness,” a condition which, in Sinister, leads directly to flight from the literal home followed immediately by an encounter with, and the realization of, bodily death.11

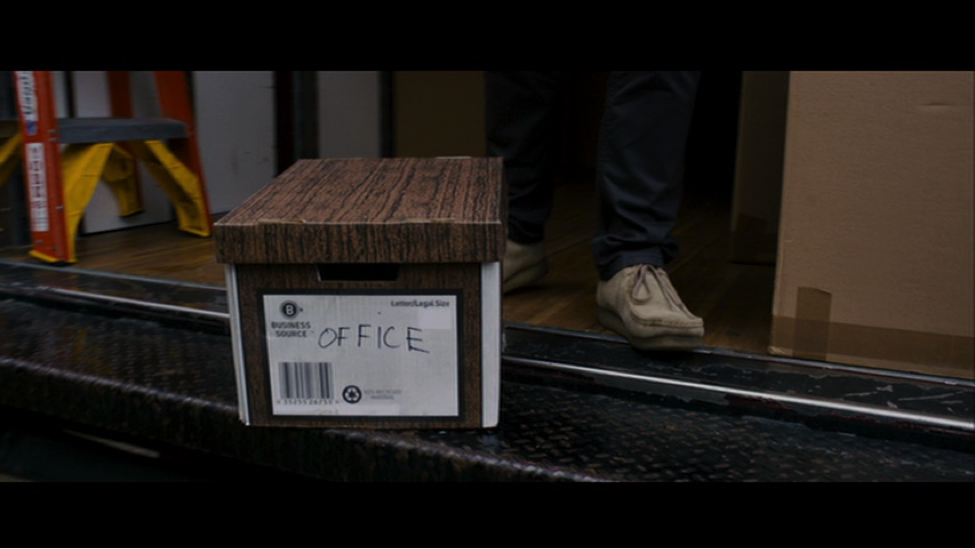

The existential danger of moving is signified prominently through the presence of the cardboard moving box, which functions as a recurring element of the film’s mise-en-scène. After the film’s opening title credit image of the prior family hanging, the first image of the Oswalts moving into their new home is a steadicam shot of the home and a moving truck that introduces a document box being slid by Ellison’s foot, which the camera emphasizes and that the viewer sees before seeing Ellison’s face (Fig. 1). Cinematographically, the box itself is emphasized in the shot, while the closely recorded sound of the box rubbing against the floor of the moving truck singles it out as sonically important, especially coming on the heels of the aurally intense title credit. The curse of Bughuul is transmitted to Ellison and his family evidently through Ellison’s screening of the film, which he finds in a moving box in the attic. In this respect, the moving box becomes more than a literal container for film images and their apparatus, but a kind of media object and apparatus itself insofar as it functions not only as a storage container for images, but also plays a crucial role on communicating the material effects of those images to unsuspecting victims. In this sense the moving box also operates as a figure for exchange-value itself, as a container that abstracts its specific contents into a nondescript and homogenous form in order to mediate exchanges between use-values. The box therefore engages, albeit in a domestic rather than a commercial and transnational register, what Alberto Toscano and Jeff Kinkle have termed a “poetics of containerization,” insofar as the process of moving homes is “marked by a certain fixation on the ‘box’ as refractory to feeling and cognition, but also as the possible source, when cracked open, of an insight into the freight of bodily suffering that the seamlessness of circulation renders invisible.”12 This transmitting function of the box becomes especially apparent when Ellison destroys the 8mm film bearing Bughuul’s image and moves his family back into their old home, only to find that the box of film has mysteriously persisted, and is sitting in his attic in the same position as it was in the other home. The box thus functions both metonymically and metaphorically as a symbol of the anxiety attached to moving as a feature of home ownership (and also as a marker of anxieties surrounding media, insofar as it functions as media, as I discuss below).

Fig. 1: The Moving Box

The moving box is a nearly universal component of the contemporary Western experience of changing homes, and its strong visual and textural qualities give sensuous weight to moving as more than merely an abstract concept. Metaphorically, the flickering dichotomy of presence and absence that is present in the box as something that produces anxiety because it can be forgotten and left behind, or as in the case of Sinister, precisely because it cannot be forgotten and relegated to the past, is invoked through the home movies’ supernaturally cursed persistence through time and across national space. Once again, Heidegger’s notion of anxiety is useful here: the moving box, therefore, serves as a signifier of generalized existential anxiety, in the Heideggerian sense, insofar as it indicates both the temporary loss of those household objects, which would normally be ready-to-hand, and an attendant invitation to reflect upon the totality of one’s material “involvements.”13

This anxious relation to personal property reflects the film’s concern with material object loss on the one hand and the plague of that which continues to depress the value of real property on the other. The pressure that it exerts, not only on Ellison but also on the family is especially emphasized when Ellison finds Trevor having a night terror inside a moving box. Although this sequence functions spectatorially in part for shock value, it also resonates with the moving box as a container of terror‒as a medium that holds and transmits uncontrollable effects on the human body and psyche‒and as a marker of the subject reduced to a container and transmitter for spasms of pure affective intensity. This spasmodic intensity is in turn relayed through the formal shock of the “jump scare” to the spectator of Sinister, momentarily collapsing the film’s strata of speculation—economic, surveilling, and narrational—into a momentarily unified affective figure.

The film draws a strong connection between containerization and mediation not only at the level of the body and of the moving box, but also in terms of the house itself, which takes on the functional role of a media object in the film. It serves as a container and conveyor for the demonic curse and its haunted images, but also becomes a text open to processes of inscription. Ashley’s practice of drawing pictures on the walls in her room makes this especially apparent (Fig. 2). Initially, she and Ellison agree that the drawings are to stay inside the room, but as the film progresses, the art spreads beyond the boundary of the room while becoming more explicit in its reference to the Stevensons and the curse. The Oswalts’ new house, and indeed many of the houses in Sinister, are porous, leaky containers that fail to hold their ‘proper’ contents. In this respect, the formal structure of the curse illuminates the problematic disjunction between the form and content of the commodity itself, in which value is never self-contained, but always (and only) established in a movement of exchange that transgresses the material boundary of the commodity object.14 What is distinctive about the curse, and telling of the film’s post-recession context, is that it becomes activated precisely through viral movement, of people from house to house and images from person to person. Therefore, as a figure for the dialectical paradox of value itself, the curse and its related images come to stand not only for home value in a local sense, value that the Stevenson house is unable to retain and the loss of which seems to spread virally from one move to another, but also of a more global and financialized market value, which emerged from subprime home loans, proliferated through markets worldwide, and then leaked out from the market’s every pore during the 2008 financial crisis.15

Fig. 2: House as Medium of Inscription

III. Spectatorship as Surveillance, Surveillance as Labor

Ellison’s research connects anxieties around labor, value, and economic security, but it is also, as I have suggested, fundamentally a labor of surveillance and forensic scrutiny. Ellison’s research takes a decisive turn once he discovers the box of Super-8 reels in the attic of the new home, shifting his attention to a close examination of the footage itself rather than an investigation of the lives of the murder victims or a tracing of the steps of the official police investigation. His labor of narrative reconstruction is intimately connected to a voyeuristic scrutiny of the ostensibly private ‘home movies’ of the previous families of victims, including footage of their grisly murders. In the film, the acts of narrative construction and of surveillance are increasingly blurred and intermingled. Describing what she terms “surveillance cinema,” Catherine Zimmer stresses the “multiple mediations that occur through the cinematic narration of surveillance, through which practices of surveillance become representational and representational practices become surveillant, and ultimately distinctions between the two begin to fade away.” For Zimmer, ‘surveillance cinema’ involves not only the iconographies of surveillance but also the ways in which narrative structure performs the work of joining the form and content of surveillance together.16

Sinister does precisely this work, not by explicitly representing the activity of surveillance as it is conventionally understood (which is to say as involving the visual or auditory monitoring of the activities of others in such a way that they are thereby placed under control) but, instead, through the way in which the film problematizes twin concerns regarding the ability of the image to yield evidentiary truth and the troubled relationship between such imagistic evidence and narrative. Notably, despite Ellison’s deep entanglement in (as it turns out, entirely justified) paranoia, he is in fact not the person who solves the mystery and finally puts the narrative pieces together ‘correctly.’ Rather, it is the apparently oblivious comic-relief character ‘Deputy So and So’ (the only name the character is given) who is able to complete the forensic reconstruction and author the ‘correct’ narrative of how and why the murders took place. For both Ellison and the spectator of Sinister, first-blush appearances deceive and do not provide a firm basis for evidentiary reasoning or narrative construction. The ways in which the film explores and articulates anxiety regarding surveillance can be organized along four distinct modes of anxiety involving activities of surveillance: ethical anxiety, spatial/panoptic anxiety, textural anxiety, and material anxiety, ranging from the largely abstract and impersonal (ethical), to the concrete and medium-specific (material).

In the first, most impersonal sense, Ellison’s surveillance labor is troubled by the ethically compromised nature of the research. Most obviously, Ellison intends to leverage the gruesome suffering and violent deaths of the Stevenson family to turn a profit with which to feed his own family. The ethics of the book project are called into question very early in the film by the sheriff, who adds that moving into the actual home of murder victims is “in extremely poor taste.” The fact that the sheriff’s ethical critique is leveled in the form of an aesthetic judgment is particularly apt, reinforcing the tension between the ostensibly distinct domains of legal justice and commercial production. When Ellison initially realizes that he has found film footage of not just the Stevenson family being murdered but other families as well, his initial response is to call the police department to report the existence of additional evidence. This reaction demonstrates an awareness of the fact that, as Benson-Allot has described, Ellison is not supposed to be viewing these images, and that they are best handled by the proper authorities. As he calls the police, however, he comes face to face with several copies of Kentucky Blood, which seem to prompt him to hang up and fail to disclose the existence of the evidence to the police. Ellison appears to be hamstrung, caught between the economic imperative of writing another bestseller and the voyeuristic exploitation of the suffering of others, and seemingly pinned between the book and the film as two forms of media with competing moral and commercial imperatives.

Ellison is corralled by these contradictory impulses, and this ethical confinement is reflected formally in the film’s mise-en-scène through the spatial layout of Ellison’s office space (Fig. 3). This room in the Oswalts’ new home is separated from the rest of the house, kept under lock and key, and like Marx’s factory in Capital, access to the room is clearly restricted to admittance on Ellison’s business only. The room is structured with a screen hanging on one wall, on which Ellison projects the home movies, and an arc of bulletin boards on the opposite side of the room, onto which Ellison posts photos, documents, maps, and other bits of evidence and some of which, true to the conspiratorial nature of the investigation, are connected to each other with generically and iconographically appropriate lengths of string. This circular research space, in which Ellison is centrally positioned at the seat of projection, simultaneously evokes a panoptic structure while confining Ellison by surrounding him with images. The relationship between central viewing position and peripheral image evokes a panoptic set of subject/object relations that would place Ellison at the controlling center of the scenario, ideally positioned to survey the evidence and make appropriate connections between disparate facts. The rectangular shape of the bulletin boards, with both images and text pinned to them and which Ellison can manipulate, suggests the boards as a material extension of Ellison’s laptop screen, and in this sense he is surrounded by screens containing various types of visual media. If the ability to panoptically survey media is initially aligned with empowerment and control, this position quickly becomes troubled, and ultimately reversed over the course of the film. The supernaturally haunted image seems to increasingly possess power over Ellison and the family, effectively inverting the power relations of the panoptic position, since the image is capable of looking back at the viewer, returning the gaze from a variety of spatial positions.

Fig. 3: Ellison’s Office

The reversal of the panoptic gaze is literalized in the film when an image of Bughuul, in a paused digital video, turns its head to stare directly at Ellison, who is looking away and does not notice (Fig. 4). This moment in the film, which is presented as a ‘jump scare’ for the audience, does more than simply demonstrate the haunted image’s supernatural, frightening sense of liveness through an unexpected reversal of subject/object relations. It also transforms the relationship between surveiller and surveilled as it becomes clear in this moment that while Ellison was looking for the mysterious murderer of families, Bughuul has been surveilling Ellison, and from a heretofore unknown position.17 The reversal thus enacts a form of what Steve Mann, Jason Nolan, and Barry Wellmann have termed “sousveillance.” As opposed to surveillance, in which power is asymmetrically held by the surveilling authority, sousveillance (‘sous’ meaning “under” in French, rather than the “over-sight” of surveillance) designates a mode of surveillance that makes use of “panoptic strategies to help [individuals] observe those in authority.”18 Sousveillance is theorized as a tool with which to hold powerful entities accountable by effectively surveilling the exercise of panoptic authority. Here, however, it is deployed as a troubling and vertiginous mise-en-abyme of power relations, which undermines the visual authority of the gaze through its reversibility. Like the anamorphic skull in Holbein’s “The Ambassadors,” Bughuul’s gaze functions as an annihilating trap for the surveilling gaze, insofar as it transforms the surveilling subject into the object of an even more comprehensive and controlling vision.19 If Lacan’s point about the skull, however, is that it figures the anchor of the unrepresentable real at the core of the imaginary-symbolic matrix, then in Sinister this disruption of the real possesses an animate vitality that goes beyond the static gaze of Holbein’s skull, since Bughuul’s agency as a destructive force is tied directly to movement, of the head within the supposedly static image, and of the curse through the supposedly stable home and its value. Bughuul is, in W.J.T. Mitchell’s twist on Walter Benjamin, a wholly biocybernetic image, straddling the paradoxical lines between movement and stasis, vitality and inertness, and subject and object.20

Fig. 4: Bughuul Stares Back

As with Benjamin’s original formulation, Bughuul, as a cybernetic image, also, and in a new register, embodies the paradox of value, with its dialectical tensions of movement, vitality, and circulation on the one hand, and stasis, inertness, and objectification on the other.

The status of Bughuul’s existence as verifiable visual evidence is also troubled in the film, both in the scenes leading up to this pivotal scare and in the scares involving the demon that happen afterwards. Ellison initially notices the presence of the demon in one of the home movies, entitled “Pool Party.” As Ellison watches first-person handheld footage of a family being drowned, he notices the demon as a human figure underwater in the pool, who turns his head towards the camera. (Retrospectively, it is unclear whether Bughuul’s direct address is supposed to take place in the event depicted, or whether this is his first attempt to surveille Ellison.) Ellison stops the projector, holding the image as a still on the screen, and walks up to investigate the image more closely, but the film, as though of its own will, suddenly catches fire, destroying the film frame with Bughuul most clearly visible. Although the fire is ostensibly the consequence of the highly flammable film stock, or perhaps of Bughuul’s supernatural ability to destroy the image in order not to be seen and exposed, it is striking that the image catches fire not once Ellison sees it but once the shadow of his hand crosses the demon’s face. Although Ellison does not touch the image, his shadow does, and this transmedial interaction between different types of images (and different forms of indexical signifier) is suggested as the true cause of the fire. This moment is the first but not the last in which competing ontologies of media, identified principally through texture, come into tactile conflict with disturbing results. Each jump scare in the film involving Bughuul, including the one previously described in which the image seems to move to look at Ellison, involves an ontological and textural transgression between forms of media.

The last and most strongly material form of concern surrounding surveillance is produced through Ellison’s response to the rupture of the film medium, which is to physically splice the film back together. After the fire that ruptures the film, Ellison watches an online instructional video to learn how to edit film, then splices the Super-8 film back together. He also splices film much later in the film when he discovers the “extended cut endings” to the home movies, which reveal the fact that the families’ children are in fact the killers. Montage, as a material and narrative practice, is closely imbricated with the logic of surveillance. Garrett Stewart begins his recent study of surveillance and media by declaring that “[a]ll montage is espionage.”21 Stewart goes on to heavily complicate this relationship, but the connection between the narrative logic of editing practice and the informatic logic of surveillance remains closely imbricated. Similarly, Zimmer also notes that the innovation of continuity editing was developed to handle chase scenes, which are themselves predicated on visualizable crime and discipline.22

The suggestion here is that continuity editing operates on a logic of motivated viewing of particular events in space and time‒that events are viewed for some particular reason. Likewise, surveillance as a mode of information gathering is also motivated by the presumption that surveillance images produce factual information or intelligence that can be narrativized and made meaningful. Surveillance and narrative cinema both assume motivation, and reply on practices of forensic spectatorship (frame scanning, inference making, hypothesis-testing) in order to produce a causal chain of events, that is, a narrative.

Thus, the fact that Ellison materially handles the film medium and physically splices the film back together evokes the relationship between continuity as a system of formal rules, technology as a prosthetic means, and knowledge as a governing goal. This knowledge is troubled by the structure of the home movies themselves, which in each case but the last feature two sections, separated by a jarring cut. The films open with evidently pedestrian footage of the families engaging in mundane daytime activities, meaningful only to the families themselves, before cutting to the more disturbing and valuable footage of those same families being hanged, drowned, and burned alive. In each case, Ellison is never able to see the murderer, nor is he able to understand the motivation for the murders. The one instance of Bughuul that appears on film makes an exception that proves the rule, since the immolation of the medium enacts the disappearance of the motivating force from the film image, at precisely the point where a suturing edit is located. The “extended cut endings” finally provide the necessary visual evidence, but do so only after they are edited into, and onto the film at a material level as a form of narrative surplus. Ellison’s labor of meaning construction, ‘prodused’ through the physical act of editing, is therefore intimately tied to the presence or absence of visual evidence from which to make inferences and draw conclusions via processes of surveillance. His ability or inability to author, or forensically reconstruct, a narrative, and in turn to ensure his family’s financial stability, is inseparable from his ability, quite literally, to be a successful content creator.

IV. Media Transition and the Hauntology of the Digital

The two primary threads of speculative anxiety that are articulated in and by Sinister‒the trauma of economic recession and its deleterious effect on property value and the troubled nature of an economically necessary surveillance that bears witness to such familial trauma‒are united together in Ellison’s spectatorship of the home movies footage, especially through its remediation as digital video. The film stages the linkage between these two concerns through a series of textural and ontological transgressions, involving both the film/video image and its associated sound design, the medium-specific affordances of video compared to film, and the loss of control over the proliferation of digital images that sits at the core of the logic of haunting presented in the film. In this attention to texture and to the sensuous qualities of the film as highly significant stylistic parameters for understanding the stakes of the film’s narrative and thematic content, I draw on Ian Garwood’s study of hapticity and sensuousness in relation to narrative sense. Garwood claims that in certain films, “sound and images acquire a ‘living’ texture that engages the viewer’s senses in a particularly intensive way,” which Garwood identifies with the “sensuous quality of film.” He argues that “a film’s sensuous qualities can be intimately connected to its storytelling processes.” In other words, the sensuous and textural qualities of film can function as highly relevant stylistic parameters that shape an audience’s understanding of a film’s story, and especially its story as a kind of aesthetic world unto itself. Following this lead, we can see how qualities of aural and visual texture articulate thematic concerns regarding the status of media in the film, and how the film’s use of texture connects to its concerns with property and surveillance.23

The very first image in Sinister, prior to the steadicam shot of Ellison pushing the moving box, is a title sequence shot that shows the Stevenson family being hanged on 8mm film (Fig. 5). The perpetrator is hidden from sight behind a tree, barring visual access to the cause of the violence. Indeed, it may seem initially that there is no material, causal agent responsible for the hanging, as the image is composed to suggest that the pole saw used to hang the family is moving on its own, rather than being manipulated by an unseen entity. The image contains a number of aspects that gesture towards its status as a film image, including its noticeable grain, the extension of the image beyond the visible scene to the edges of the celluloid strip on both the horizontal and vertical axes. The image also seems to lack its own synched soundtrack. The sound design during this opening section consists of multiple overlapping scratching noises and sounds of static, which are eventually replaced by the dominant sound of a film projector’s rapid clicking, the latter of which enters the mix when the title of the film appears and the moving image freezes to a static frame. The image and sound relations here establish the film’s first kind of textural transgression through the intermingling of scarcely distinguishable noises of analog and digital media technologies. The audio mix features three distinctive sounds of static, one a very high-frequency piercing sound, one a lower-frequency sound that evokes the sound of television static, and one an even lower pitched sound recalls the sound of an overworked hard-disc drive on a computer. Of each of these sounds, none properly belongs to the film image, either diegetically or technologically, a point that is forcefully clarified when the sound of a projector is finally made audible. Rather, this opening uses the sound of media other than film, and sounds which suggest media in a form of mechanical distress (a television without a signal, computer components operating at maximum capacity), to produce a disturbing soundscape of media under duress. If the film image here can be said to possess the kind of “living texture” that Garwood supposes, that texture is skittish and anxious, evoking the sound of television static, and the connotation of a media transmission without content‒an empty container. From the outset of the film, the mixing of media is associated with trouble, death, and an inability to identify the source of the problem.

Fig. 5: Sinister’s Title Credit

Later in the film, when Ellison first cues up the film of this incident, this sound design is largely repeated, with the diegetic sound of the projector in Ellison’s office added as a component of the sound mix. The sounds of dysfunctional media, evoked through scratching sounds that would generally indicate the possibility of damage to the media object itself (celluloid being etched, a hard drive burning out), draw specially close attention to the materiality of the media as an object that is subject to damage, that does not persist immaculately through time but can (and in the case of the celluloid does indeed), like the film’s cursed families, come to a sudden and violent end. The emphasis on the material frailty of the image is also reflected through the visibility of the screen’s surface during projection. Ellison’s makeshift screen consists of a bed sheet safety-pinned to the wall, and while the film footage is projected, wrinkles in the screen material are clearly visible. These wrinkles give the image a textural quality that forces the viewer to see, as well as hear, the image as having a material presence, embodied in a particular form of materiality. The physical embodiment of the image, coupled with its distressed sense of ‘liveness,’ are crucial elements in establishing the credibility of the supernatural entity that haunts the image itself and transcends the ontological boundary between an imagistic netherworld and normal, lived reality.

Central to the film’s concern with technologies of surveillance is the fact that Bughuul, whose living embodiment resides within images of himself, is only ephemerally detectable on film, but is consistently visible on digital video. It is only on his Macbook that Ellison is able to detect the presence of Bughuul in each of the other (non-swimming pool) home movies, whereas they were undetectable when projected on film (and in fact, as Sinister’s director and producer attest in on the DVD commentary track, simply not present in the film image at all).24 It is only through the digital video camera’s surveillance of the act of film projection, and through the affordances of digital video in terms of the ability to pause a video, enlarge an image, adjust image contrast, and ultimately through the ability to print physical copies of the image, that Ellison is able to secure documentary evidence that Bughuul exists and was involved with the family murders. Citing films such as The Blair Witch Project (Sánchez and Myrick, 1999) and Paranormal Activity, Zimmer notes that found-footage horror films tend to employ competing logics of image quality and texture with respect to film versus video, with the cinematic image rendered as clear and transparent, while the video image tends to be rendered as low-grade, unclear, and ambiguous.25

Sinister, interestingly, reverses this dichotomy, at least initially, by presenting celluloid film footage as heavily textured and material, while the digital image appears not only clean and transparent, but actually enhances the viewer’s powers of observation by making evident aspects of the image that were obscure and invisible on film. However, rather than identifying this visual documentary faculty with security and verification, the film depicts the technological capacities of video in terms of a terrorizing surplus value, effectively exchanging materiality of celluloid montage and its extended duration for the resolution, enhanced access, and temporal flexibility of the digital image.

In Sinister, the video image carries something extra, a deadly dangerous kind of surplus visibility, which in turn produces a surplus of value in the form of Bughuul. Insofar as Bughuul persists through time, and across the series of exchanges of images from one family to another, and one haunted house to another, the demon represents what Derrida calls the ‘hauntological’ aspect of value: the commodity’s distinct being of ‘time out of joint,’ since it carries within it the congealed form of labor-time.26

The commodity form is haunted by the ontological transgressions of exchange between time and space, between quality and quantity, and between present and past. Bughuul literally embodies this hauntological quality of the digital image, which is stylistically manifested precisely at moments of transition and confusion between analog and digital media ontologies. Bughuul stands ultimately as a figure for the immateriality of value itself, and especially of its increasingly digital form in the 21st century global economy. The demon figures a hauntologically unstable surplus value, both formally in terms of its excessive presence within the image and in a literal economic sense, insofar as Ellison’s discovery of Bughuul forces him to accept far more than he has bargained for in investigating the Stevenson murders, ironically rendering the real true crime story Ellison never gets to write, one in which evidence of supernatural demons exists, both immensely valuable and potentially apocalyptic, given Bughuul’s ability to spread through images of itself.

Anxiety associated with the surplus value of digital video is also identified with a transgression of conventional frame boundaries associated with visual media forms. If the spontaneous combustion of Bughuul’s effigy indicates an evacuation of the film image, and his ability to take possession of the video image and move within it indicates a dangerous surplus, then this logic of the frightening danger of media ultimately extends to Sinister itself, qua media object, through Bughuul’s two jump scares that come late and at the very end of the film, respectively. In each instance, the frame encourages the viewer to focus attention on an object deep in the represented space, while Bughuul’s face pops out into the side of the frame, much closer in the visual field than the focus of attention, producing a particularly startling bodily jolt. These scares extend the logic of the curse’s transmediality, that it moves from medium to medium, from film to video, video to house, house to movie screen, gaining strength with each new embodiment, eventually seeming to homologously take possession of Sinister itself, and even perhaps to seem to extend into the viewer’s own home-viewing space, once again temporarily collapsing the strata of speculating relations that structures the film before retreating back into the image within the image.

V. Conclusion: Speculation, Theory

Sinister’s greatest virtue as a commentary on the cycle of found footage/faux footage/ verité horror may be its ability and willingness to explore the complex and changing relationships between media platforms and narrative construction, and between surveillance and labor, and perhaps most importantly of all, its attempt at mutually framing these sets of activities in terms of each other, generating a productive and valuable moment of conceptual and theoretical exchange between ostensibly discrete social and economic realms. In doing so the film, like its protagonist, reveals a cultural, technological, and economic epistephilia at its core, which is also perhaps to say a desire for cognitive mapping, or even of cognitive forensic surveillance. In an entertainment economy and cultural ecology that is dominated by transmedia franchising and cinematic universes, Sinister represents a localized attempt to think the place of small films within the vast and unrepresentable totality, both within the context of entertainment, and within the broader economic context of finance capitalism, the financial crisis, and its continuing aftershocks. It seeks to do both for the entertainment industry and for domestic security what Fredric Jameson’s conspiracy films did for the capitalist world system, namely to “constitute an unconscious, collective effort at trying to figure out where we are and what landscapes and forces confront us” under the present economic and political circumstances.27 Low-budget horror, with its media-industrial ephemerality and disposability, is perhaps not a ‘poor’ but only a precarious person’s cognitive mapping, whose images of traumatic circulation are, in this instance, quite literally and meaningfully ‘degraded’ in form.

Sinister attempts to trace and map out the shifting social and economic forces of post-crisis financialized capitalism, and does so by foregrounding the parallel structures of the viral circulation of digital images and of the commodified financial abstractions that constitute finance capital as such. As Peter Osborne has argued, “[i]n the digital image, the infinity of exchange made possible by the abstraction of value from use finds an equivalent form.” The ontology of digital photography therefore echoes the commodity form, since neither makes visible its referential value, evincing no necessary bond between use and exchange value. De-realized digital images, like commodities, are therefore subject to infinite exchangeability, and indefinite degrees of abstraction.28

Sinister figures not only this ontological homology and potential exchangeability, but of its consequences for the body exposed to them, a body forced into the precarious self-employment of the neoliberal gig economy in which speculation, and its ambiguously productive and destructive vicissitudes, can be imagined as compensated and creative labor, as an explanatory theoria that helps capital circulate freely, in exchange for one’s life. In this sense, Ellison’s speculative labor, in its domestic and traumatic context, becomes a kind of dialectical inversion of the global and seductively glamorous, if also problematized, Wall Street financial speculation depicted in The Wolf of Wall Street (Scorsese, 2013), and one that refuses to disavow the body of the observer in the processes of narrative construction and financial valorization.

Speculation itself, therefore, becomes the common term that unites Sinister’s economically and nationally allegorical tendencies, and in a manner that formally and aesthetically draws together the spatial components of Ellison’s detective work through his surveillance of the visible image and the temporal components of the investigation through his failed attempt at narrative construction. Speculation, as Sinister shows, stands as the unifying conceptual intersection at which questions about the relationships between economy and culture, as well as historical events and their aesthetic representation, can and must be reconsidered and rearticulated within the political-economic, historical, and aesthetic moment of the present. This is because, as the film adamantly shows, speculation cannot be divorced or abstracted away from the laboring body that performs it, nor from the material body in which the abstractions of financial speculation ultimately land. Hence, the film figures speculation, in the form of Ellison’s active spectatorship, as a concept in a way that necessarily synthesizes both the figurative sense of the speculative, as well as the concrete, embodied, and laboring subject of speculation, and of a speculative economy.

Yet, as the final image and closing jump-scare of the film reminds us, we too are perceptually, affectively, and economically implicated, both as embodied spectators and as speculators. In doing so, the film once again collapses its speculative strata into an affective figure, and moves beyond a representational practice of cognitive mapping and into the realm of what Steven Shaviro theorizes as affective mapping, by productively expressing the speculative relation between observers and images as a relation between the audience and the film.29

- Blake, Linnie and Xavier Aldana Reyes, “Introduction: Horror in the Digital Age” in Digital Horror: Haunted Technologies, Network Panic and the Found Footage Phenomenon (London: I.B. Tauris, 2016), 11. ↩

- Grant, Barry Keith. “Digital Anxiety and the new Verité Horror and SF Film,” Science Fiction Film and Television 6:2 (2013): 153-175. ↩

- Caetlin Benson-Allot, Killer Tapes and Shattered Screens: Video Spectatorship from VHS to File Sharing (Berkeley: UC Press, 2013), 168, 171, 184. ↩

- Fredric Jameson, “Culture and Finance Capital,” Critical Inquiry 24:1 (Autumn 1997): 252. ↩

- W.J.T. Mitchell, What do Pictures Want? The Lives and Loves of Images (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), 318. ↩

- This loosely designated second cycle of found-footage horror films would include, among others, V/H/S (2012), Oculus (Flanagan, 2013), Unfriended (Gabriadze, 2015), in which the investigation of found footage plays a substantial narrative role, as well as immensely financially successful The Conjuring (Wan, 2013) and The Conjuring 2 (2015), in which aural and visual surveillance technologies play a less central, but still significant role. In these latter two films, the clairvoyant capacities of paranormal investigator Lorraine Warren (Vera Farminga) also take on a somewhat similar surveilling function. ↩

- Julia Leyda, “Demon Debt: Paranormal Activity as Recessionary Post-Cinematic Allegory,” Jump Cut 56 (Fall 2014). Accessed March 1, 2017. https://www.ejumpcut.org/archive/jc56.2014-2015/LeydaParanormalActivity/text.html. ↩

- McClanahan, Annie. Dead Pledges: Debt, Crisis, and Twenty-First Century Culture (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2017), 143. ↩

- I owe this latter observation to Cameron Kunzelman. Oculus (Flanagan, 2013) also contains the forbidden father’s office as a trope for the danger and uncertainty of labor, and makes it a much more central aspect of the narrative of the film. ↩

- See Giovanni Arrighi, The Long Twentieth Century: Money, Power, and the Origins of Our Times (London: Verso, 1994), 300-24. ↩

- Martin Heidegger, Being and Time, trans. John Macquarrie and Edward Robinson (New York: Harper and Row, 1962), 233. ↩

- Toscano, Alberto and Jeff Kinkle. Cartographies of the Absolute (Winchester: Zero Books, 2015), 200. ↩

- Toscano, Alberto and Jeff Kinkle, 200 ↩

- David Harvey, A Companion to Marx’s Capital (London: Verso: 2010), 17. ↩

- The film’s narrative also makes an oddly astute psychoanalytic connection between the economic and psychoanalytic senses of foreclosure. Lacan defines foreclosure (verwerfung) as a hole or lack in the Name-of-the-Father, which prevents proper signification and the functioning of the symbolic order, contributing directly to the condition of psychosis. In Sinister, the literal psychosis and absence of the father, and his symbolic role in maintaining structure of the household, leads to Ashley’s failure to adopt appropriate behaviors, and eventually to her demonic possession. This prevention of proper symbolic and psychic functioning is seemingly caused by Ellison’s inability to make payments on the Oswalts’ original, larger home. (See Jacques Lacan, Ecrits, trans. Bruce Fink, (New York: Norton, 2006), 465-6, 479. ↩

- Catherine Zimmer, Surveillance Cinema (New York: NYU Press, 2015), 2. ↩

- This moment in the film also seems to literalize the moment in Paranormal Activity when Katie, who is being similarly haunted by a demon, explains to her husband Micah that the entity can hear everything they say, a moment that similarly enacts a reversal of the relationship between surveiller and surveilled. The reversal is extended in Oculus, where the agency of the mirror as an image-object is of primary narrative interest. ↩

- Steve Mann, Jason Nolan, and Barry Wellman, “Sousveillance and Using Wearable Computing Devices for Data Collection in Surveillance Environments,” Surveillance & Society 1(3): 322. ↩

- See Jacques Lacan, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis (New York: W.W. Norton, 1981), 88-9. ↩

- Mitchell, What do Pictures Want?, 318. ↩

-

Garrett Stewart, Closed Circuits: Screening Narrative Surveillance (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), ix. ↩

- Zimmer, Surveillance Cinema, 7. ↩

- Ian Garwood, The Sense of Film Narration (Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh Press, 2015), 3. ↩

- Robert Cargill and Scott Derrickson, “Commentary,” Sinister, DVD, directed by Scott Derrickson (Santa Monica, CA: Summit Entertainment, 2013). ↩

- Zimmer, Surveillance Cinema, 77. ↩

- Jacques Derrida, Specters of Marx, trans. Peggy Kamuf (New York: Routledge, 1994), 201-2. ↩

- Fredric Jameson, The Geopolitical Aesthetic: Cinema and Space in the World System (Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1995), 2-3. ↩

- Peter Osborne, “Infinite Exchange: The Social Ontology of the Photographic Image,” Philosophy of Photography 1:1 (January 2010): 67. ↩

- Steven Shaviro, Post-Cinematic Affect (Winchester, Zero Books, 2009), 2-3. ↩