By Genevieve Flavelle

Photo credit: Allyson Mitchell, Lesbian Rule, 2013. Courtesy of the Artist.

On a warm fall evening in 2015 a lesbian feminist entity known as KillJoy opened her fang bearing mouth in the center of Los Angeles’s Plummer Park. Inviting audiences into her inner sanctum, the maligned matriarch elicited delight, horror, fear, sentimentality, laughter, and reverence for lesbian feminist herstories1 Viewers grouped together in line with friends, or perhaps friendly strangers, awaiting their turn to experience the novelty of a Lesbian Feminist Haunted House. Reaching the front of the line, visitors’ introduction to KillJoy’s Kastle was brusque as Valerie Solanas was back from the dead and working the door!2 Brandishing her infamous S.C.U.M. Manifesto, a ghoulish Solanas instructed groups that what they were about to experience would not be “part of the ordinary.” As a group was being informed about nudity and instructed not to take flash photography, I joined in time to be advised that the “KillJoy’s Kastle is best viewed by the light of your pussy—if you have one.” I quickly explained, as I was in costume as a Riot Ghoul, that I had left my post as a performer in the Kastle to do the tour as a participant.3 Solanas instructed us to select a group name. After deciding on a suitably gory yet gay name my group was ushered through the large fangs that adorned KillJoy’s Kastle’s entrance by a series of handsome undead security personnel. We were seated inside a courtyard on camping chairs arranged on a green plastic lawn facing a stage; large pink letters above the stage unapologetically proclaimed that we were now in the realm of “LESBIAN RULE.” On stage, a zombie-lesbian folk band performed. The two zombies openly bickered about their past relationship as lovers and proclaimed they had been resurrected together to perform as a form of purgatory after murdering each other when their personal and professional relationships turned sour. Playing their own repertoire, as well as covers of lesbian folk classics, the zombies performed their anachronism self reflexively, making snide comments about current political affairs and comparing their experiences of the 1990s lesbian heyday “when it was possible to have a lesbian band” with current culture, which they seem to regard as a dystopic failure of their vision for a feminist future. Other performers watched or circulated through the crowd, singing along and providing additional sympathetic or goading commentary. After a short performance that left me feeling both entertained and berated, my group was summoned to meet our “demented” women studies tour guide. We assembled in front of an aggressively colorful entrance bearing the title of the “Emasculator” to begin our journey through KillJoy’s Kastle.

Allyson Mitchell and Deirdre Logue, KillJoy’s Kastle (2015), view of entrance. Courtesy of the artists.

KillJoy’s Kastle: A Lesbian Feminist Haunted House was created by contemporary Canadian artists Allyson Mitchell and Deirdre Logue in collaboration with over a hundred artists and performers. First installed in the fall of 2013 in Toronto, KillJoy’s Kastle was resurrected for a second time in Los Angeles by the ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives.4 KillJoy’s Kastle drew on the form of Evangelical Christian Hell Houses, that dramatically act out scenes of sins such as homosexuality, abortion, drug use, drunk driving, and suicide in an attempt to guide viewers, especially teenagers, towards the path of Evangelical Christianity.5 In her examination of the motivations that structure the creation and performance of evangelical Hell Houses, scholar Ann Pellegrini suggests that to understand how Hell House performances work critics need to move beyond the “overt content or theology of Hell Houses (what Hell Houses say) and focus instead on the affectively rich worlds Hell House performances generate for their participants (what Hell Houses do).”6 For my analysis of KillJoy’s Kastle I will similarly focus on what KillJoy’s Kastle did and the affectively saturated world that it created for its participants and performers.

Allyson Mitchell and Deirdre Logue, KillJoy’s Kastle (2015). Courtesy of the artists.

KillJoy’s Kastle employed a similar performance format as Hell Houses but toured its audiences through a reanimation of lesbian feminist herstory designed to “pervert, not convert.”7 Simultaneously utopic and dystopic, KillJoy’s Kastle was advertised as a, “sex positive, trans inclusive, queer lesbian-feminist-fear-fighting celebration”.8 The Haunted House brought “dead” theories, ideas, movements, and stereotypes back to life with queer flair as “Riot Ghouls”, “Paranormal Consciousness Raisers”, “Zombie Folk Singers”, “Ball Busting Butches”, “Four Faced Internet Trolls”, and “Polyamorous Vampiric Grannies”. KillJoy’s Kastle drew on Mitchell’s “Deep Lez” philosophy/methodology to weave past forms of lesbian feminism together with contemporary queer politics. Styled with Mitchell’s signature maximalist art aesthetic, KillJoy’s Kastle was an immersive experience that brought both initiated and uninitiated audiences on a campy jaunt through the complexities of lesbian feminist herstory. Drawing viewers in through the promising novelty and theatrics of a “lesbian feminist haunted house,” Mitchell and Logue utilized in turn humor and discomfort to negotiate audience engagement with difficult, politically and emotionally charged lesbian feminist content.

The creation of KillJoy’s Kastle as an immersive performative space allowed the work to operate on an affective level by drawing on the personal and collective emotions and experiences of viewers. KillJoy’s Kastle specifically drew on the analysis of negative affects by queer theorists as an embodied site for interrupting and challenging narratives of liberal progress. Theorists such as Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick (2003), Heather Love (2009), José Estaban Muñoz (2006), Sara Ahmed (2004, 2010), and Ann Cvetokich (2003, 2012) have positioned negativity (shame, anger, depression, and unhappiness) as a starting point to theorize resistance to hegemony and imagine other ways of being in the world. Ahmed traces how claims to happiness makes certain privileged forms of personhood valuable while labeling those who do not conform as, “troublemakers, dissenters, killers of joy”.9 KillJoy’s Kastle positions the stereotype of the feminist killjoy as its starting point for exploring fraught feelings around lesbian feminism. The Haunted House attempted to resurrect ‘lesbian’ as a potential site of radical identification, rather than one of de-politicized apathy or shame. Mitchell and Logue grappled with some of the harmful and problematic aspects of lesbian feminism that caused the movement to lose relevance while also exploring how dominant society actively maligns otherness to maintain supremacy.

Audiences at Killjoy’s Kastle were introduced to the figure of the feminist killjoy at the beginning of the tour, when a demented women’s studies guide explained that while feminist are commonly portrayed as “happiness murderesses,” it is more than understandable to be in a bad mood after “millennium upon millennium of persecution, ridicule, erasure, and abject misunderstanding.”10 In the Promise of Happiness, Ahmed theorizes the feminist killjoy as an outsider figure whose agency is stripped by the discourse of happiness as an unhappy subject, a subject whose “failure to be happy is read as sabotaging the happiness of others.”11 Ahmed draws on the work of feminist, black, and queer scholars to construct an alternative history of happiness, one that centers unhappy subjects. KillJoy’s Kastle attempted to position unhappiness as a viable political position while critiquing the social portrayal of feminists as unhappy subjects. It was also at this early moment in the tour that guides attempted to articulate KillJoy’s Kastle double portrayal of lesbian feminists; as wrongful maligned, and as truly monstrous. Demented women’s studies professors gave an explanation along the lines of this;

let me get this crooked for you- some lesbian feminists are maligned- pushed into corners and intentionally wounded by lesbophobes, misogynists and the like…there are other lesbian feminists who are indeed monstrous. Ones who would rather stomp their own movement, resting comfortably in race and class privilege, than budge on stale ideas about gender and sex and bodies. Let’s face it, it can all be very confusing even if you are an insider like me…chained to this duty.12

The haunted house attempted to contend with both the historic and contemporary racism of White Feminism, and the transphobia of trans exclusionary brands of radical feminism.13 By animating lesbian feminist stereotypes as undead characters the haunted house grappled with how the past haunts the present and used satire to make problematic figures at times funny and at other times genuinely scary. This approach asked a lot from audiences, for some the work was experienced as a enlightening theatrical romp through a history only experienced second hand and for others it was a path truly haunted by violence.

Allyson Mitchell, KillJoy’s Kastle (2013), Ballbusting Dykes smashing plaster cast truck nutz. Photo Lisa Kannakko, courtesy of the artists.

KillJoy’s Kastle took feelings both as its subject and its material by twisting and queering the subjective and the social, the past and the present.14 Feminism as a social, political, and intellectual movement has been fraught with schisms, losses, infighting and feelings. Ahmed theorizes feelings as the site of embodied meaning making, social ordering, and perhaps most importantly the process in which the very boundaries of individuals and communities are drawn and redrawn.15 Mitchell’s work has consistently drawn on the collective feelings that surround feminism and lesbian feminism. In 2009 she penned a manifesto for her methodology titled “Deep Lez I Statement.” Deep Lez is a queer critique of lesbian feminism’s essentialism, transphobia, and whiteness. As a methodology it attempts to weave together elements of lesbian feminism and contemporary intersectional queer politics to create a both/and sensibility that embraces multiple histories and perspectives. Mitchell conceptualized Deep Lez as an experiment, a process, an aesthetic, and a blend of theory and practice that aims to acknowledge and address histories of conflict and erasure in feminist and queer movements. Such negotiations are far from simple and Deep Lez is meant to be “a macraméd conceptual tangle” that questions how art and politics integrate.16 Deep Lez was conceptualized to acknowledge the urgent need in contemporary queer and feminist movements “to develop inclusive liberatory feminisms while examining the strategic benefits of maintaining some components of a radical lesbian theory and practice.”17 Deep Lez works such as KillJoy’s Kastle are carefully situated not “to simply hold on to history, but rather to examine how we might cull what is useful from lesbian herstories to redefine contemporary urban lesbian (and queer) existence.”18

Allyson Mitchell and Deirdre Logue, KillJoy’s Kastle (2015), Lesbian Feminist Graveyard. Courtesy of the artists

In her Deep Lez practice Mitchell’s aesthetic choices express and manipulate her theoretical subjects. Employing devalued and discarded handicraft materials such as macramé, crochet, and fun fur to create immersive works Ann Cvetkovich describes Mitchell’s choice of physical materials as an extension of her conceptual materials, arguing that Mitchell uses “that which has been rejected as outmoded or déclassé” as a trigger for deep feelings.19 Cvetkovich elucidates that for Mitchell, “the strong and frequently negative feelings that are attached to objects that are sentimental, cute, garish, cheap, or excessive resemble the feeling associated with both fat girls and feminisms, and this reservoir of shame, abjection, and mixed feelings is a resource for queer reparative strategies.” 20 The hand crafting of all of the elements of KillJoy’s Kastle with kitsch materials such as papier-mâché, yarn, and fun fur reflect the bygone eras being reanimated and set the camp tone of the work.

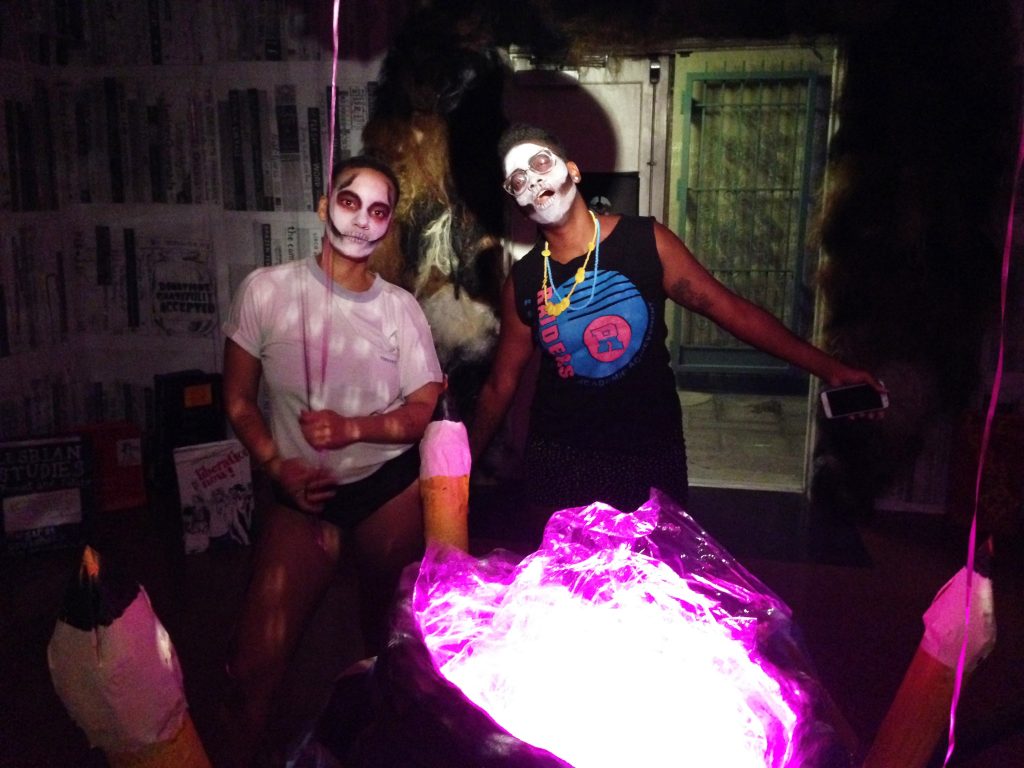

The original construction of the Toronto haunted house involved 558 hours in the studio with 15 artists making the work from 9:00 am to 4:00 pm between May and September, as well as an additional 352 hours installing the exhibition in the space.21 Mitchell and Logue spent weeks installing and creating new rooms for the LA iteration with local LA artists. Often the crafting of the room extended onto the bodies of the performers. In the yarn cobwebbed den of the Polyamorous Vampiric Grannies the live performer was almost indistinguishable from her panty hose doll coven counterparts—until she moved and scared the audience that is. KillJoy’s Kastle draws on elements from Mitchell’s earlier immersive installations such as Hungry Purse (2004-ongoing) her series of macraméd vagina dentata room. Works such as Big Trubs, a 12 foot tall feminist fun fur deity, and hand drawn Lesbian Herstory Archive wallpaper that depict the bookshelves at the archive also make appearances. In KillJoy’s Kastle the wallpaper outfitted a feminist library in which Riot Ghouls, an undead twist on the 1990s feminist Riot Girl movement, held an intimidating “Women Studies Dance Party”. The Riot Ghouls, of which I was a member for a weekend, danced around a cauldron adorned with oversized pencils and crystals under the light of a disco ball while brandished oversized papier-mâché queer and feminist theory texts. While some audience members were immediately intimidated by the sweaty scene, others tried to join the dance party or were quickly drawn to the texts on display. The Riot Ghouls intervened to make audience members feel unsettled by brandishing confrontational stares, frenzied dance moves, academic jabs such as “have you actually read this?” and disdain streaked laughter. The Riot Girl movement, widely celebrated and historicized as the beginning of Third Wave Feminism in the US, was activated in this incarnation as a troubled space of insiders and outsiders. The context of the library/archive further questioned whose work we celebrate, teach, and cite, and the inaccessibility of academic spaces.

Allyson Mitchell and Deirdre Logue, KillJoy’s Kastle (2015), Riot Ghouls gathered around their cauldron. Image by author.

KillJoy’s Kastle created an experience that operated on both affective and intellectual levels, inviting viewers to “dare to be scared by gender-queer apparitions, ball-busting butches, and never-married, happy-as-hell spinsters.”22 Viewers were warned that KillJoy’s Kastle is a haunted house of “freaky feminist skill sharing and paranormal consciousness-raising,” which “reanimates the archive of lesbian herstory with all its wonders and thorny complications.”23 Employing the form of a haunted house to exploit its participants’ good and bad emotional connections to lesbian feminism, KillJoy’s Kastle celebrated lesbian feminism’s legacies while critiquing how they operate in the present. Like evangelical Hell Houses, the Haunted House utilized its audience’s common understanding of the horror genre and haunted house format to set a certain tone of address that did not scorn the serious but situated it within a performative and humorous fiction. Pellegrini notes that for evangelical Hell Houses the, “engagement with popular culture provided an idiom and affective style that could transcend simple denominational divisions within Protestantism.”24By packaging itself as a novel performative art event, KillJoy’s Kastle drew in a diverse audience with a mix of personal, cultural, and educational associations to lesbian feminism. While KillJoy’s Kastle was not constructed to scare in the same way as a Hell House, it was designed to make audiences feel things. KillJoy’s Kastle drew on the intensity of affective sensibility, and used a participatory performance format to transform its audiences.

Though loosely associating with the horror genre, KillJoy’s Kastle’s direct negotiation of abjection and the female grotesque take the form of a carnivalistic spectacle. Analyses of the grotesque have existed in art and aesthetics for centuries and in the contemporary age the grotesque has been primarily theorized in two discursive frames: the uncanny and the carnivalesque.25 The carnival grotesque is associated with outrageousness, humor, and comedy, while the uncanny is associated with horror, strangeness, and the tragic. The uncanny is interior while the carnival is exterior—both rely on the trope of the body. Conceived of first and foremost as a social body, the grotesque is associated with degradation, death, filth, and, importantly, rebirth. KillJoy’s Kastle is positioned as a carnival grotesque, a spectacle that invites viewers to participate in its subversive form. Scholar Mary Russo wrote The Female Grotesque: Risk, Excess, and Modernity (1994) in response to the normalizing strategies and rhetoric of 1990s feminism. Revisiting earlier risk-taking feminist works, Russo draws on the work of Mikhail Bakhtin to theorize the female grotesque as an important location to approach the question of difference and the counter production of knowledge. She theorizes the female grotesque as a body that is, “open, protruding, irregular, secreting, multiple and changing; it is identified with non-official ‘low’ culture or the carnivalesque, and with social transformation.”26 Russo asserts that making a spectacle of oneself is an inherently female transgression and an important and potentially transformative intervention into the social. In Killjoy’s Kastle participants enter the public body of the maligned and abjected lesbian feminist killjoy. Constructed as a site of queer feminist insurgency the haunted house produces, reflects, and deconstructs cultural anxieties, threatening excesses, and “dangerous” affects rather than defensively opposing them. For example, social anxieties about unmarried spinsters, predatory lesbians, and the dangers of non-monogamy are embraced through the production of the Polyamourous Vampiric Grannies who relax a in fear inducing cobweb adorned den of domestic non-normativity.

Allyson Mitchell, KillJoy’s Kastle (2013), Polyamorous Vampiric Granny coven. Photo: Lisa Kannakko, courtesy of the artist.

Important for the affective dimension of this analysis is the role and participation of the audience. Russo describes the relationship of the audience to the grotesque body of carnival festivity as not distanced or objectified in relation to its audience, but rather that the audience becomes part of the spectacle. Russo states that in a carnival;

Audiences and performers were the interchangeable parts of an incomplete but imaginable wholeness. The grotesque body was exuberantly and democratically open and inclusive of all possibilities. Boundaries between individuals and society, between genders, between species, and between classes were blurred or brought into crisis in the inversions and hyperbole of carnivalesque representation.27

KillJoy’s Kastle not only blurred the boundaries between such distinctions, it also invited its audience to participate in its performance. Participants touched various props, sang along with Zombie Folksingers, smelled the pussy juice of the Paranormal Consciousness Raisers, punched the pillars of oppression, danced with Riot Ghouls, drank witch piss with Stitch Witches, and verbally processed their experiences with real life Killjoys. The audience was active in its witnessing of and participation in KillJoy’s Kastle as a queer space and spectacle.

Allyson Mitchell and Deirdre Logue, KillJoy’s Kastle (2015), view of the Pillars of Society that the Intersectional Activist fights. Image courtesy of the artists.

Functioning as site of insurgency Russo argues that the carnival and the carnivalesque “suggest a redeployment or counter production of culture, knowledge, and pleasure.”28 She argues that through its “multivalent oppositional play” the carnival “refuses to surrender the critical and cultural tools of the dominant class.”29 Camp similarly is a tradition of queer performance that redeploys dominant culture from a position of debasement. Camp, like affect, is difficult to define or to pin down with any sort of specificity.30 I suggest that KillJoy’s Kastle uses camp as a style of artifice to perform anachronisms, the outmoded, and stereotypes as humorous characters. Feminist theorist Pamela Robertson argues that the “camp effect” occurs at the moment when cultural products of an earlier moment of production have lost their power to dominate cultural meanings and become available for redefinition. She argues that camp “redefines and historicizes these cultural products not just nostalgically but with a critical recognition of the temptation to nostalgia, rendering both the object and the nostalgia outmoded through an ironic, laughing distanciation.” 31 Art historian David Getsy cautions that it is,

important to remember that camp is never just about fun. It values the devalued, and its energy comes from its rejection of “commonly accepted” worth. For this reason, the object or image appropriated as camp becomes a site for the interrogation of the ways in which cultural and economic values are assigned. This comes from the brazen and intentional misuse and misreading that camp perpetrates. Camp’s valorization of culturally derided objects and images upholds the weak as the strong, the bad as the good, and the useless as essential. Its love of obsolescence is a form of resistance to normative values.32

KillJoy’s Kastle used camp in this critical mode, playing on nostalgia and deep feelings without collapsing into a depoliticized sentimentality, while also making space to valorize the non-normative. For example, one of the first scenes audiences encountered inside of KillJoy’s Kastle is the mirrored den of the Paranormal Consciousness Raisers. Guides introduced the group of tie-dye wearing ghosts writhing on piles of furs and pillows while examining their genitals in hand mirrors, as the “Great spirits of y’or who come together to share truths about their lives – a valuable strategy gleaned from civil rights activism – now desperately trapped in a cultural stereotype about lonely uptight suburban white women gazing at their own vaginas.”33 The Paranormal Consciousness Raisers revived the stereotype of the pussy gazing consciousness raisers as a over the top sex positive show and tell, moaning “my pussy…my pleasure” and “cunt cunt cunt.” Like the Riot Ghouls, the Paranormal Consciousness Raisers performed a campy counter production of lesbian and feminist stereotypes to question dominant feminist narratives and engage audiences intellectually, emotionally and physically.

Allyson Mitchell, KillJoy’s Kastle (2013), the Paranormal Consciousness Raisers. Photo:Lisa Kannakko, courtesy of the artist

Scholar Jayne Wark notes that queer artists are often engaged in a sustained negotiation with popular culture and use camp and drag to assert the visibility of queer and marginalized identities. Wark argues that the use of parody and other forms of humor function both as a means of rebellious effrontery and as an empowering transformation.34 In KillJoy’s Kastle camp humor and performance was used to disarm a potentially hostile audience composed of participants that perhaps take lesbian feminism too seriously, or alternatively take their disavowal of lesbian feminism too seriously. KillJoy’s Kastle did not use camp to parody dominant culture directly but used camp to intervene in dominant culture’s portrayal of lesbian feminists and other queer subjects with a knowing self-mocking humor. Killjoy’s Kastle is a Deep Lez parody of lesbian feminism as it is perceived by both outsiders and insiders to the movement. Additionally, the very form of the haunted house, as noted earlier, is a co-optation and parody of a recognizable form of pop cultural entertainment. Wark suggest that queer artists’ appropriations of popular culture has enabled them “to avail themselves of its pleasures and artifice, and to enact a critical mimesis of its entertainment strategies so as to expose and politicize those power relations.” 35 Wark suggests that through this form of critical mimesis camp performances “not only rely upon modes of popular entertainment, but also actively assault these modes by way of the excess of queer camp, the intertextual meanings of parody, the exaggerations of satire and the defiance of self-mocking humor.”36

KillJoy’s Kastle is a camp performance that simultaneously stages a queer assault on a mode of popular culture entertainment while using its form to stage a self-mocking humorous portrayal of dominant culture’s dismissal of lesbian feminism. The Haunted House speaks back to dominant culture while also engaging its audience in the difficulties of navigating nostalgia. The performance engages critically with both the external oppression of dominant culture, and the internalized oppression and conflicts of movement building to create a work that is not simply reactive but builds an active space of memory and self-reflexive critique.

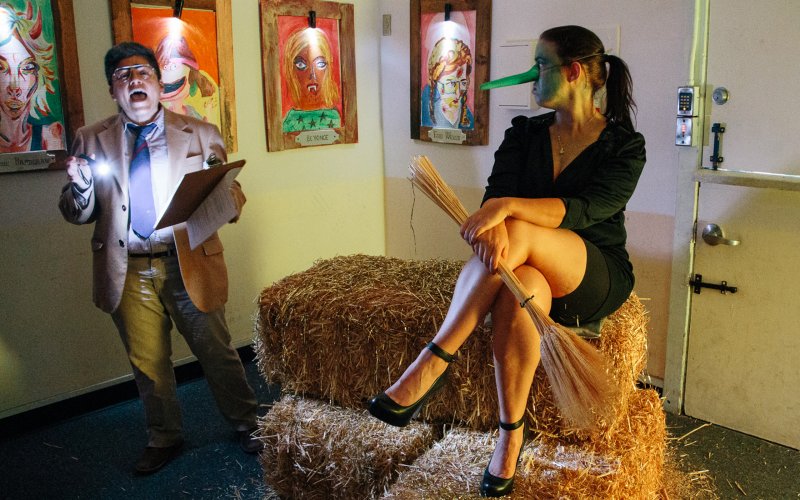

Allyson Mitchell and Deirdre Logue, KillJoy’s Kastle (2015), Straw Feminist Hall of Fame. Image courtesy of the artists.

To give KillJoy’s Kastle broader context it is important to situate traditions of gay and lesbian theatre and performance within the lexicon of political struggle. The history of queer theatre is very much invested in the idea of community and the assumption that community is a political necessity and viable possibility. Queer playwright Tim Miller notes, “the history of lesbian and gay theatre accepts the notion of community as axiomatic and stages the struggle to sustain and expand community as one of its primary objectives.”37

As the topic of KillJoy’s Kastle and its Deep Lez methodology is the negotiation of queer and feminist movements and political feelings, the feelings of its audience are an important aspect of the piece. Miller posits that queer audiences bring a specific social paradox to theatrical occasions. The support of much of the audience results from a desire to be in a crowd of other queer people:

And, yet, on the other hand, many spectators also attend community-based events in order to defy the politics of sameness. Rather than upholding an uncritical stance towards the notion of queer community, many queer spectators set out to put pressure on this concept. This desire never rests, but rather prefers to unsettle the comforts of identity politics in the very space of its enactment. Thus, the impulse to seek community comes out of a series of relational and often contradictory tendencies ranging from the desire to be part of a community, however fabricated or temporal that concept of community may be, to the desire to test individual identity in opposition to the very concept of lesbian and gay community itself.38

Some of this paradox may be glimpsed through participant’s recorded reactions to KillJoy’s Kastle and the community debates that took place online during both the 2013 and 2015 incarnations.

Allyson Mitchell and Deirdre Logue, KillJoy’s Kastle (2015), Four Faced Internet Troll. Image courtesy of the artists.

After the opening night of KillJoy’s Kastle in 2013 a significant amount of critique and dialogue began taking place on the Facebook event page. Mitchell made the show as easy to attend as possible; the installation was not in a museum or gallery, it was free and accessible by public transit, and so—though only performed for one night—a broad range of visitors (not just those immersed in the art world) experienced the work. In my research I found a range of personal reviews on blogs and a huge amount of discussion on Facebook. It is interesting to note that the installation garnered far more attention and discussion from feminist and queer media sites than contemporary art sites. A blog post by Toronto based multimedia artist Kamplex’s was one of the first critiques posted publically, and had a significant impact on the discussion of the installation. The review was posted on Kamplex’s blog and cross-posted to the Facebook event page for KillJoy’s Kastle.39 In their review, Kamplex was critical of the lack of diversity of the performers and audience they encountered. Kamplex also discussed being adorned with unwanted glitter, feeling unwelcome by the anti-male sentiments, and the cultural appropriation parodied by a white zombie tree hunger wearing a dreadlock wig. While Kamplex noted that they appreciated the gesture of the processing room, they felt they could not just leave their feelings in the space and thus choose to make their experience public. This review triggered a large response in the form of other visitors posting critiques, a large amount of discussion then took place in the form of comments on these posts. I have chosen not to include these posts, even anonymously, as they for the most part are referential to each other, but I identified that the majority of the dialogue centered on critiques of trans misogyny, the maintenance of the structural whiteness of feminism, the consent of visitors, and the accountability of the artist. As artist Mary Tremonte aptly identifies in her discussion of the installation, “the barrage of criticism for the LFHH(Lesbian Feminist Haunted House) centered on representation and identity politics, an example of difference within difference; how multifaceted and various the identities of “lesbian” and “feminist” are, and how a diverse audience responded to the project’s provocations.”40

While the amount of discussion generated demonstrates the affective resonance of the piece, and brings up the very challenges and negative feels that KillJoy’s Kastle is attempting to work through, a discussion of the controversy is tricky. As Miller notes, the queer audiences that attend works such as the KillJoy’s Kastle are “dynamic social groups that cannot readily be reduced to a monolithic, static whole.”41 The audience brings a range of expectations, experiences, desires, and criticisms, which interact with the affect staged in KillJoy’s Kastle and produce a complex range of experiences. It is also difficult to discuss the controversial nature of an artwork without centering the negative or dismissive reactions to a work. Jennifer Doyle discusses exactly this issue in Hold it Against Me: Difficulty and Emotion in Contemporary Art (2013), arguing that genuine discussion of how controversial art practices actually work is often sacrificed in favor of sensationalist stories about shock.42 This certainly took place with the KillJoy’s Kastle and many people I spoke to who had not seen the piece were often dismissive based on what they had heard of the controversy. This reaction is especially present when discussing lesbian feminist discourse in contemporary queer or feminist contexts. As Elizabeth Freeman notes, in many academic and activist circles any mention of lesbianism seems “to somehow inexorably hearken back to essentialized bodies, normative visions of women’s sexuality, and single-issue identity politics that exclude people of color, the working class and the transgendered.”43 I often witnessed a thoughtful understanding of how Mitchell was trying to negotiate the difficulties of different feminisms as the subject of KillJoy’s Kastle bypassed in favor of quick dismissive opinion.44 One aspect that was most often cited in the critiques of KillJoy’s Kastle I encountered was with regards to one of the hand painted signs in the entrance. The sign was one of many which advertised the various attractions of the Haunted House and gave warnings. The specific sign that caused outrage read, “Don’t trip on the severed penises”, which was cited as being oppressive to trans women and evoking the transmisogyny of many older feminists. This sign was actually countered within the installation by a sign that read “Beware: No transphobic satanic humans allowed”. For the LA installation, rather than completely discard the controversial sign Mitchell and Logue changed the sign to read “Don’t trip out, there’s no severed penises”. Doyle notes that it may seem counterintuitive to shift our attention from the controversy surrounding the work to the work itself, as it makes sense to view the scandalized reactions to a work as an important point in understanding how it challenges its viewing public. Doyle argues, however, that “when we allow our thinking to be oriented by the terms and values of controversy, we take our cues from people who have not seen the work or who have seen it and rejected it with the force of a violent allergy” and this suppresses the existence of the work’s core audience who seek out and support, and invest in the artist’s work.45 Controversy in art is also tricky because many artists who become embroiled in public controversy purposely, such as Mitchell, set forth to challenge their audiences. Doyle argues that the ways in which these kinds of works may affect viewers and, “make us angry or leave us unsure how to react, confused about our own emotions and the place of those feelings in relation to the work itself” is actually part of the work. She argues that, the audience’s limits figure explicitly in such works, and clearly we need to think carefully about how these limits ought to inform our critical practices. The defensive critical posture we adopt in the face of controversy fails us because it does not give us room to acknowledge how much failure, refusal, and rejection inform the poetics of the work in question.46

Responding to the volume of criticism voiced over Facebook in 2013, Mitchell made her own Facebook post in which she acknowledged KillJoy’s Kastle had the limitations of her own “shortcomings, blind spots, humor, passion, creativity and privileges.”47 Mitchell clarified that she attempted to create a non-oppressive and inclusive space, however admits that the space inside KillJoy’s Kastle was still informed by the problems and politics of the outside world, and intentionally the Kastle was “built to be a place of horror for many people for many reasons. This includes the horror of whiteness, and the horror of cis-genderedness”. She notes that with limited success she and her collaborators attempted to create a non-racist and trans inclusive, accessible space. Evident in the post is the contradictions of trying to make a safe space in which oppressive ideas are examined. In her post Mitchell refused to name all of the identities and subjectivities of her collaborators, in an effort to avoid falling into a pit of identity politics, however, she noted that in the construction of the Kastle she attempted to “replace essentialist representations of vaginas and vulvas with unexpected ones as well as work with a diverse crew of performers and representations of bodies in order to undermine whiteness.” Mitchell acknowledged “the space and concept are haunted by the undead ghosts and spirits of the whiteness and transmisogyny of feminisms past and present” while also drawing attention to “the iconographies of queer and feminist art histories and activist spirits that will not die.” On the whole, she stated that the project, “is meant to be an apt and symbolic funeral for dead and dying lesbian feminist monsters as well as a place to cathartically face fears, self-critique, and contractions.” In a later published response to a published art review that criticized KillJoy’s Kastle for being not welcoming enough to a diverse audience and focusing too heavily on the difficult attributes of feminism, Mitchell articulated that feminism is a sticky place and it was her intention as an artist to have her audience question their own place within feminism. She asserts that feminism should not be a place of comfort, nor “a secure, stagnant engagement.”48 She also reiterated that as a haunted house KillJoy’s Kastle is meant to be scary, and as an art piece it is meant to be critically engaging. Throughout both of these response Mitchell situated KillJoy’s Kastle as an artwork and herself as an artist repeatedly. She encouraged a continuation of the dialogue but offered no solutions.

Allyson Mitchell and Deirdre Logue, Killjoy’s Kastle (2015), Danger Rangers.

In her discussion of the carnival, Russo argues that the extreme difficulties of producing lasting social change should not diminish the usefulness of these symbolic models of transgression. She suggests that the histories of marginalized people and alternative cultural activity are never as neatly closed as structural models might suggest.49 The grotesque body is always an “open, protruding, extending, secreting body”, it is the messy body of “becoming, process, and change.”50 While the carnival has suggested some preliminary “acting out’” of the dilemmas of femininity, Killjoy’s Kastle acts out the dilemmas of feminist herstory, and it’s messy. The piece raises the question of how to negotiate the complex histories and the haunting of movements. It proposes both humor and also discomfort as legitimate methods of accessing and opening up difficult conversations. KillJoy Kastle’s feminist queer camp performance is complex as it takes on both dominant and internalized stereotypes of feminists and queers while also creating a new form of haunted representation. KillJoy’s Kastle seeks to problematize the viewer’s understanding of both the past and the present. By mixing high and low culture, theory and craft, humor and trauma, Killjoy’s Kastle presents a range of subjects mediated through camp performance, and draws on the feelings of its performers and audience to becomes a site of insurgency and openness in which dialogue and transformation may take place.

Entering into the cool blue light of the processing room, my tour of KillJoy’s Kastle had ended and I pulled up a white fur stool perfectly stained with fake menstrual blood to begin processing the reactions and feelings of my tour group. My group’s processing session was mediated by three real life killjoys, most of whom were feminist academics. They introduced themselves and we did a name and pronoun go-around before they asked us about our feelings and reactions to the piece. They responded to viewer’s concerns and questions, and posed questions of their own when the conversation stagnated. The space was not uncritical and often the killjoys expanded on and complicated the questions and reactions viewers put forth. The audience was not expected to leave their feelings in this room; it was a space of accountability, and though the artists and other performers were not present, the killjoys shared the audience’s reactions and feelings with the larger whole and this feedback shaped the performances to come. This was KillJoy’s Kastle’s version of a Hell House Heaven Room where viewers recommit to God and pray, but in lesbian feminist heaven everyone’s voice is heard and afforded critical value. After being thanked for attending and speaking, my group exited through the Ye Old Lesbian Gift Shoppe. I bought t-shirts emblazoned with queer and feminist slogans for all my dearest queer kin and then looped back to my post as a sweaty laughter-wielding Riot Ghoul.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to Dr. Kirsty Robertson for her encouragement and support as my supervisor. Also I am immensely thankful to Allyson and Deirdre for inviting me to LA and encouraging me to participate in KillJoy’s Kastle. Thanks also to the incredible performers of both iterations of KillJoy’s Kastle for creating such a spectacular queer spectacle.

- Herstory is history written from a feminist perspective, emphasizing the role of women, or told from a woman’s point of view. The term was widely used in the feminist movement in the 1970s. ↩

- Valerie Solanas, S.C.U.M. Manifesto, (New York: Olympia Press, 1968). ↩

- This system was devised and implemented on the second night of the performance after some difficulties on the first night keeping groups together throughout the entire tour. It also allowed the audience further participation and identification with the piece. Interestingly many of the names were quite campy and some even came very close to the names of the characters in the haunted house. ↩

- The ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives is the largest LBGTQ archive in the world. The ONE Archives at the USC Libraries and the ONE Archives Foundation together organize a range of exhibitions on queer art and culture at ONE’s main location near the University of Southern California and at the ONE Archives Gallery & Museum in West Hollywood. For KillJoy’s Kastle The ONE Archives facilitated the use of an unused building in Plummer’s Park in West Hollywood. ↩

- Ann Pellegrini, “’Signaling Through the Flames’: Hell House Performance and Structures of Religious Feeling”. American Quarterly 59.3(2007): 912. ↩

- Pellegrini, 912. ↩

- “KillJoy’s Kastle: A Lesbian Feminist Haunted House”, ONE Archives, last accessed 06/07/2017, <http://one.usc.edu/killjoys-kastle/>. ↩

- ONE Archives. ↩

- Sara Ahmed, The Promise of Happiness, (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2010.) 17. ↩

- Allyson Mitchell, Performance Script for Killjoy’s Kastle, Courtesy of the Artist, 2013. ↩

- Ahmed, The Promise of Happiness, 66 ↩

- Mitchell, Performance Script for Killjoy’s Kastle ↩

- The most extreme version of transphobic and transmisogynistic feminists have been termed TERFS (Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminists), see this list of common hateful behavior performed by TERFS against trans women such as outing trans women to their employers, Christian Williams, “You Might be a TERF if”, <http://transadvocate.com/you-might-be-a-terf-if_n_10226.htm>. ↩

- Queer as an identity, movement, method etc. is not based on binaries and actually promotes a sabotage of “the manifold binarisms (masculine/feminine, original/copy, identity/difference, natural/artifical, private/public, etc.) on which bourgeois epistemic and ontological order arranges and perpetuates itself…the inclusive ‘gesture’ of queer therefore claims to inscribe all subordinations (of class, gender and ethnicity) into a common design while apparently respecting each subordination…in its historical and cultural specificity”. Fabio Cleto, “Introduction: Queering the Camp”, Camp: Queer Aesthetics and the Performing Subject: A Reader, ed. Fabio Cleto (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1999) 14. ↩

- Anu Koivunen, “An affective turn? Reimagining the subject of Feminist theory” in Working with Affect in Feminist Readings: Disturbing Differences edited by Marianne Lijestrom and Susanna Passsonen, (London: Routledge, 2010) 14. ↩

- Allyson Mitchell, “Deep lez I Statement,” No More Potlucks 1 (2009), last accessed 06/07/2017, <http://nomorepotlucks.org/site/deep-lez-i-statement/> ↩

- Mitchell, “Deep lez I Statement.” ↩

- Mitchell, “Deep lez I Statement.” ↩

- Ann Cvetkovich, Depression: a Public Feeling, (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2012) 185. ↩

- Cvetkovich, 185 ↩

- Allyson Mitchell, “Dear Jess Carroll”, C Magazine 123 (2014): 8-9 ↩

- ONE Archives ↩

- ONE Archives ↩

- Pellegrini, 941. ↩

- Mary Russo, Female Grotesque: Risk, Excess, and Modernity (New York and London: Routledge, 1994) 7 ↩

- Russo, 8 ↩

- Russo, 78 ↩

- Russo, 62 ↩

- Russo, 62 ↩

- In his introduction to Camp: Queer Aesthetics and the Performing Subject: A Reader, Fabio Cleto notes that, “the slipperiness of camp has constantly has constantly eluded critical definitions and has proceeded in concert with the discursive existence of camp itself.” Camp has been approached tentatively as “sensibility, taste, or style, reconceptualized as an aesthetic or cultural economy, and later asserted/reclaimed as (queer) discourse”. “Introduction: Queering the Camp”, Camp: Queer Aesthetics and the Performing Subject: A Reader, 2 ↩

- Pamela Robertson 1996, Guilty Pleasures: Feminist Camp from Mae West to Madonna (Durham and London: Duke University Press) 5. As Robertson notes, any discussion of women’s relation to camp will “inevitably raise, rather than settle, questions about appropriation, co-optation, and identity politics” but camp has been used by feminists for some time (9). In Notes On Camp Susan Sontag discusses the way of camp in terms of artifice and stylization. She notes that many of the objects prized by camp are old-fashioned, out of date because the process of “ageing or deterioration provides the necessary detachment and/or arouses a necessary sympathy”(60). She argues that things become campy not simply when they become old, “but when we become less involved in them, and can enjoy, instead of being frustrated by the failure of the attempt”(60). Additionally she posits that camp doesn’t argue that the good is bad or the bad good, what it does is to offer for art and life, is a supplementary set of standards (61). See Susan Sontag, “Notes on Camp” in Camp: Queer Aesthetics and the Performing Subject: A Reader, 53-65 ↩

- David Getsy in conversation with Jennifer Doyle, “Queer Formalisms: Jennifer Doyle and David Getsy in Conversation”, 31/03/2014, Art Journal Open, accessed 15/11/17,<http://artjournal.collegeart.org/?p=4468>. ↩

- Mitchell, Performance Script for Killjoy’s Kastle. ↩

- Jayne Wark “Dressed to Kill”. Canadian Cultural Poesis: Essays on Canadian Culture edited by Petty S, Sherbert GH, and Gérin A. Waterloo (Ont: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2006) 178. ↩

- Wark, 188 ↩

- Wark, 188 ↩

- Tim Miller and David Román, “Preaching to the Converted”, Theatre Journal, 47.2(1995): 174 ↩

- Miller and Román, 176 ↩

- Kamplex.,“Feminist Haunted House Review”, Kamplex.com, last accessed 22/01/2014, <http://kalmplex.com/2013/10/17/feminist-haunted-house-review/> ↩

- Mary Tremonte, “Monstrosities in Killjoy’s Kastle: A Lesbian Feminist Haunted House, from without and within”, marymackfemtech.wordpress.com, last accessed 7/04/2014, <https://marymackfemtech.wordpress.com/2013/12/05/monstrosities-in-killjoys-kastle-a-lesbian-feminist-haunted-house-from-without-and-within/> ↩

- Miller and Román, 176 ↩

- Jennifer Doyle, Hold it against me: difficulty and emotion in contemporary art. (London;Durham: Duke University Press, 2013)13 ↩

- Elizabeth Freeman, 2010, Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories, (London;Durham: Duke University Press) 62 ↩

- One of the best examples of this was actually a published exchange of open letters between an art writer and Mitchell. In an open letter to Mitchell published in Carbon Paper Jess Carroll criticized the Haunted House for being not welcoming enough to a diverse audience and focusing too heavily on the difficult attributes of feminism. Mitchell responded by publishing a response to Carroll’s criticisms and by extension the controversial nature of the piece has a whole in C Magazine. Allyson Mitchell, “Dear Jess Carroll”, cmagazine, (Fall 2014): 8; Jess Caroll, “Dear Allyson Mitchell”, Carbon Paper 2 (February 2014) ↩

- Doyle, 13. ↩

- Doyle, 14 ↩

- Allyson Mitchell, post on KillJoy’s Kastle facebook event page, 28/10/2013, last accessed 14/11/2017, <https://www.facebook.com/events/166258290234212/> ↩

- Mitchell, “Dear Jess Carroll”, 8 ↩

- Russo, 58 ↩

- Russo, 62-63 ↩