Table of Contents / Issue 33: After Douglas Crimp

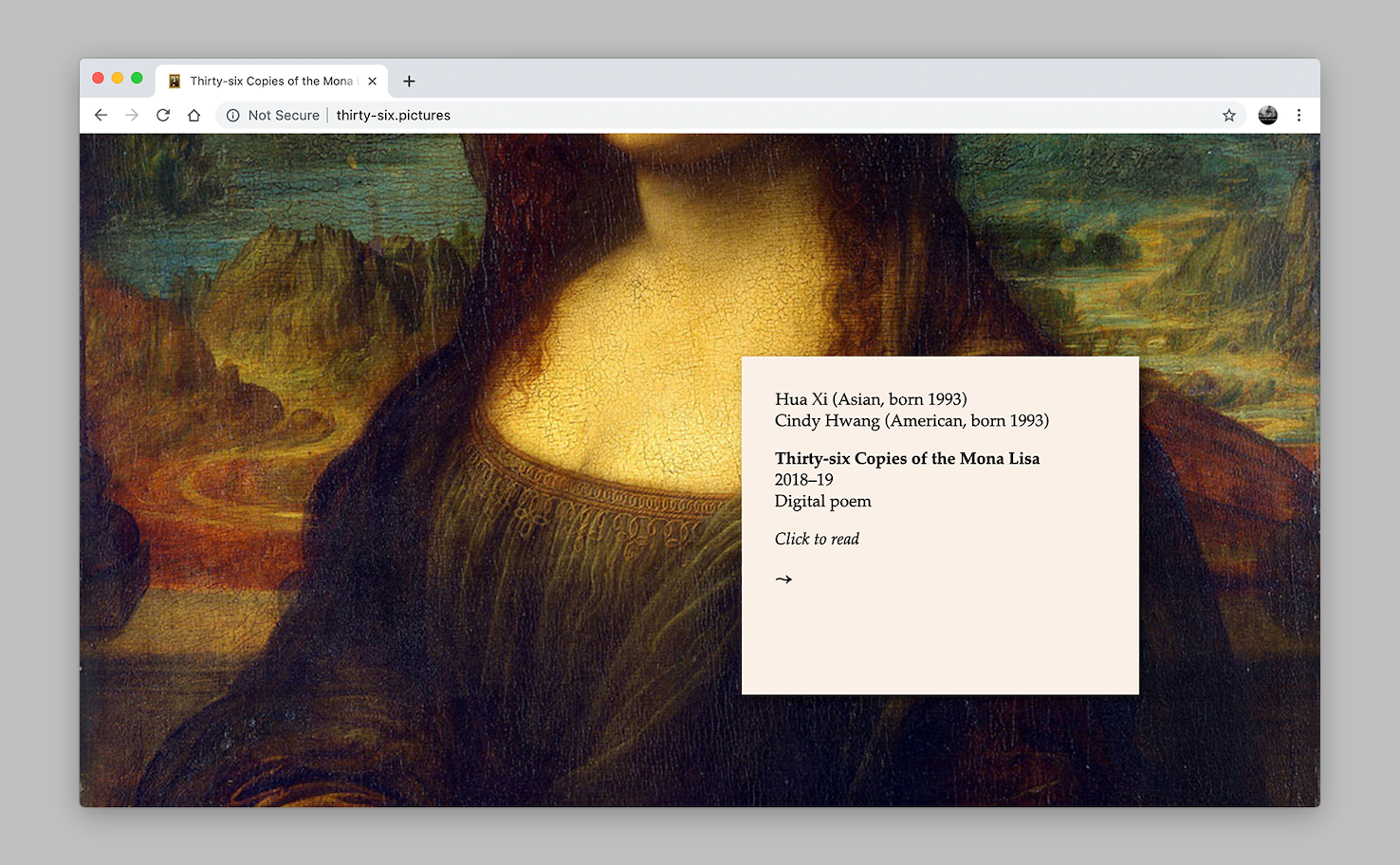

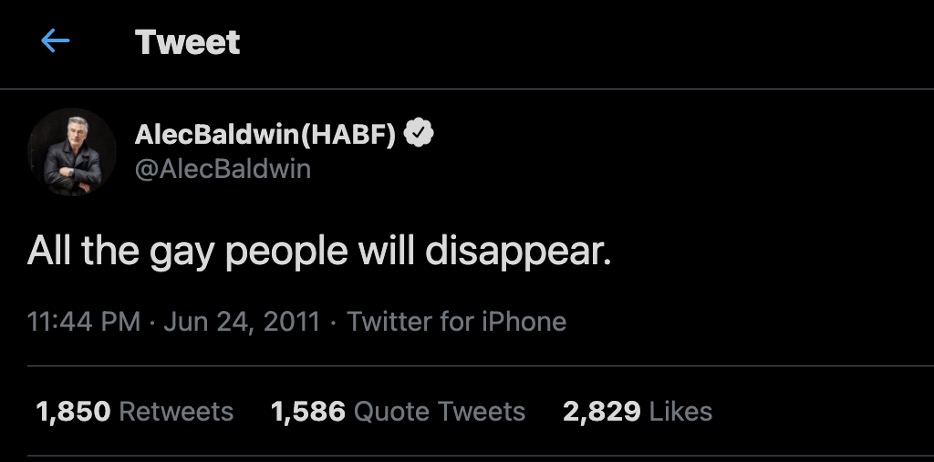

Peter Murphy, “Introduction: After Douglas Crimp” Articles Matthew Bowman, “The Haunting of Modernism Conceived Differently” Theo Gordon, “Re-reading ‘Mourning and Militancy’ and its Sources in 2022” Lutz Hieber and Gisela Theising, “Manhattan-Hanover Transfer” Christian Whitworth, “Mourning, Militancy, and Mania in Patrick Staff’s The Foundation“ Artwork Cindy Hwang and Hua Xi, “Thirty-Six Copies of the Mona Lisa” Dialogues Benjamin Haber and Daniel J Sander, “All the Gay People Will Disappear” Xiao (Amanda) Ju, “Reading Douglas” Peter Murphy, “Learning From Douglas: A Course Schedule” Questionnaire Daly Arnett, Kendall DeBoer, Bridget Fleming, Peter Murphy, “After Douglas Crimp: Questionnaire” Tara Najd Ahmadi Tiffany E. Barber Nicholas Baume Peter Christensen Amanda Jane Graham Rachel Haidu Kelly Long Shota T. Ogawa T’ai Smith TT Takemoto Gaëtan Thomas Juliane Rebentisch Ann Reynolds Marc Siegel Janet Wolff Zheng Bo Catherine Zuromskis Click here for information on the contributors to this issue.