Introduction

Dating simulations (dating sims) are a category of video games where players “date” or establish a romantic relationship with a digitally synthesized avatar in a fictional world. In this representation of the lovers’ discourse, players are presented with a series of options when interacting with characters in the game. Taking the form of specific conversational lines or gestures, these options lead to pre-determined effects that contribute to the overall disposition of the character to the player. By following the correct combination of options as programmed into the game’s system, the objective of the game in the dating sim is to achieve a blissful conclusion with the in-game character.1

However, with their apparent trivialization of what is conventionally understood as romantic love, dating sims have inevitably emerged as the subject of much controversy concerning the asocial behavior of typically young and wired adults who allegedly prefer to date a computer algorithm made visible on a gaming console, as opposed to a “flesh and blood” human being. In Japan, where dating sims are particularly popular among the otaku demographic,2 one male gamer nicknamed Sal9000 married Nene Anegasaki, a videogame character in the dating sim LovePlus.3 Although we can never be certain if this wedding ceremony between a man and his game console marked an attempt to legitimize or parody a romantic relationship, such affections according to Dominic Pettman are symptomatic of anxieties and tensions that emerge when “the most ‘human’ of experiences—intimacy or love—are increasingly being mediated by the technologies which link one agent to another.”4

Considering the similarities with the interaction experienced in human relationships, it seems the technology of dating sims involves an affective interaction with the AI (artificial intelligence) of the game system. From pets to romantic partners, these cute yet artificial objects on the screen do not simply breach the divide between the biological and technological, but continue to question the phenomenology of love as well. This is because the mode of interaction afforded by the dating sim is not much different from the communication that occurs between two enamored human lovers, for just as how the words “I love you” in the lover’s confession affects the beloved with the impulse to either reciprocate or reject that particular sentiment, the in-game characters in dating sims are also programmed to respond according to the player’s selected option.

So as opposed to thinking of the dating sim as an insidious object of individualization, there is likewise the post-humanist view that it can be understood as an extension of a technology already embedded in the lovers’ discourse. In other words, the attachment of the player to the in-game character in a dating sim is less the erosion of earlier social configurations shared exclusively between humans, than it is a repetition of the principles and structures that are initially constitutive of such arrangements. While I am in substantial agreement with this technological approach to the phenomenology of love, an emphasis on the interactivity of the romantic relationship as mediated by the dating sim is misleading as it only considers the form, but not the aesthetic conditions present to facilitate such a form of communication.

The problem can be re-phrased with the following question: If the object is to be loved, how exactly is it made to be lovable? In this article, I adopt a post-structuralist approach to critique the interactivity and aesthetics of the dating sim and argue that it exemplifies the lover’s chase for a plenitude that is only alluded to but never attained. In positing love as a technology, one understands the experience of dating sims as a reflection of an openness towards who can or cannot be loved. Revising this formulation, I argue that the design and subsequent computation of the lovable—as exemplified in the systematization of cuteness— is also a technical predetermination that re-territorializes and hence delays the plenitude of the lover’s pursuit.5

Architectures of Interactivity

I meet you. We talk, hold hands, date and fall in love. These symbolic expressions, though clichéd, nonetheless denote the interactivity of a romantic relationship taking place both in and out of the context of the dating sim. In this sense, love is first an outcome of a process, or a thing that is brought about through the application of several techniques, such as a telephone call, the giving of gifts, or the display of physical intimacy. This process is also an interactive one, for it involves communication not with the same person, but with two different individuals. These properties evidently support a technological framework for love, but what makes love—in particular romantic love—different from other communicative events?

Whether it is expressed as a verbal utterance or a physical gesture, love’s vocabulary is not immediately consistent. Because if meaning is that which emerges in the context of the communicative event, it follows that the event would open itself to not one, but a range of possible meanings. With this plurality of meaning in mind, it is not possible to first speak of love’s difference based on thematically connected expressions. Instead, I opt to frame “love” as a primary function of selecting certain meanings over others. As pointed out by Niklas Luhmann:

…communication media are initially defined merely through the naming of a function (and not yet through actual structures or processes). They link selecting mechanisms with motivational mechanisms; they motivate acceptance of the meaning thus chosen through the manner of their selection.6

For Luhmann, it would be inadequate to understand love in terms of intentions that direct behavior, because it first manifests itself as a means to an end. Love in this sense, is not meaning, but the latter’s poiesis that occurs in a subject-object relationship. That is, love as technology conditions and arguably brings forth a certain perspective that is only in relation to a being that is other to the one who holds such a perspective. We observe this in how love designates and is predicated by the “I and you” in a relationship. It is precisely because love makes meaning for someone or something else that its interactive character can be considered.

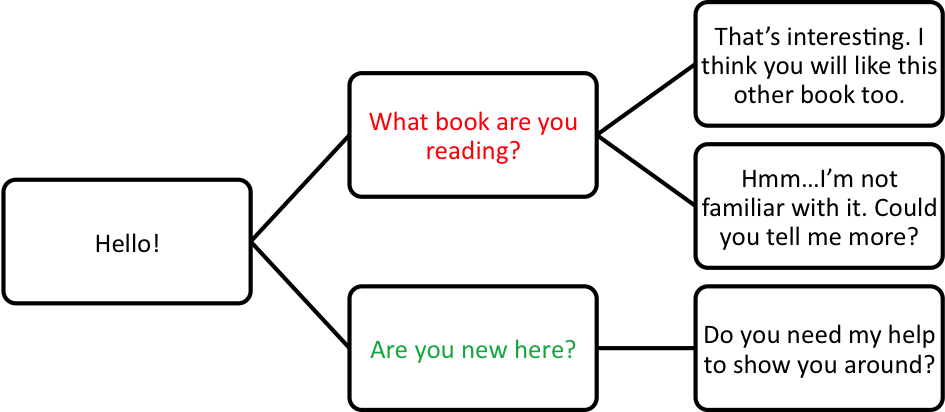

In many ways, the dating sim does not alter, but repeats and even formalizes the interactivity of love with a software construct. By giving players the space to pursue a potential romantic partner, dating sims visibly deliver a form of interactive story-telling, where players’ avatars situated in a fictional world, must navigate through various interactional scenes to find “love.” Much like the algorithmic structure of the game engine, these scenes—which come up with options that the player has to select in order to proceed in the game—are part of a dialogue tree where the options and results following the players’ selections are already programmed or written before the game begins [Fig. 1]. Players in complying with these rules are free to select any option, but can neither create, nor alter the options and their corresponding effects. Hence, the pre-determination of these options and effects is possible only through a formalization of symbolic expressions that are already intrinsic to the lovers’ discourse.

Figure 1: Basic structure of a dialogue tree showing different routes, or series of effects if either the red or green question is selected (Source provided by author).

At the same time, dating sims do not just pre-determine the means by which one repeats the lover’s discourse but also the object of one’s affections, as exemplified in the design and development of cute, digital characters that populate the narrative of the game and often function as interactive agents that have to be acquired and used. These images with their humanized artificiality, also highlight two important points concerning the affective capacities of the dating sim. First, affect emerges through a contact of difference, for if two things were identical or the same, there will be no subject-object relation to speak of. This again supports the notion that the “I and you” in the lover’s confession is dependent on both the presence of the lover and the beloved. Second, the quality of affect is dependent on its semblance to the object being simulated. As elegantly theorized by Benedict Spinoza, “If we imagine a certain thing to possess something which resembles an object which usually affects the mind with joy or sorrow, although the quality in which the thing resembles is not the efficient cause of these affects, we shall nevertheless, by virtue of the resemblance alone, love or hate the thing.”7 Cuteness in its semblance to and simulation of a lovable thing draws us to the technology in use, but it should also be noted that this particular simulation also involves a modification of the biological human that paradoxically facilitates humanization by way of a visible dehumanization. As such, there is not only a visible difference in the appearance of the object, but an emotional familiarity, even closeness that is experienced in the subject’s attachment. Both the game mechanics and cute characters are thus in my view, major components of an affective system that changes or differentiates love by extending its symbolic expressions into the digital domain.

Upon converting these symbolic expressions to computer code, the makers of dating sims effectively concretize the linguistic dimension of love itself, for such an interaction can now proceed only if the appropriate elements or symbolic expressions are in place. As observed in the myriad of romantic relationships both online and offline, love may not be the same for everyone, but its symbolic expressions do indeed form the basis of its interactivity, insofar as they have evolved to hold meaning between two agents. Non-reciprocal love too, is also a result of the exchanges that are mediated by symbolic expressions, for in deciding to reject the lover’s proposition the beloved does not fail to recognize, but is affected by the interaction.

Yet, I still contend that key features of the dating sim present several ambiguities regarding this pursuit of love. For one, the conditions making up the context of these symbolic expressions are not dependent on an autonomous subject-object relationship, but are already designed and computed before the game is played. One may claim that this pre-determination of variables in the dating sim is a form of virtualization, a position based on the philosophy of Gilles Deleuze who theorizes that “the reality of the virtual consists of differential elements and relations.”8 Adopting this Deleuzian approach, Pierre Lévy affirms the virtual’s potential for difference when he argues that virtualization is “a change of identity, a displacement of the centre of ontological gravity of the object considered.”9 These points resonate with Pettman’s idea of love as a nomadic technology and I do not refute the possibility of the dating sim as a differential maneuver. However, this difference also needs to be juxtaposed with the repeatability and pre-determination of the dating sim’s overall architecture, which includes the cute digital character.

Cute Bodies

Common to all iterations of the dating sim is the presence of the cute character, which as far as the player is concerned, designates the “you” or the lovable other in the relationship. How then do these artificial entities with generally infantilized features and body structures affect, or even interact with the player? In response to this question, we must acknowledge beforehand that the adjective of cute in this instance, no longer applies to the anatomy of biological organisms, but explicitly refers to a particular mode of character design that anthropomorphizes and animates what would otherwise be an inanimate object. Most characters in dating sims in particular, rely on the hand-drawn and highly stylized images common to Japanese manga and anime. For example, the three female protagonists, or digital partners in the dating sim LovePlus are animated as anthropomorphized caricatures, but are not in any way photorealistic representations of the human body [Fig. 2].

Figure 2: Dialogue and event scenes of the characters in LovePlus (Source: Konami)

Figure 2: Dialogue and event scenes of the characters in LovePlus (Source: Konami)

On this note, I propose that cuteness—particularly in the context of character design—is not only caricature, but also a stylized augmentation of the human body. This is an important basis, for if cute (as defined in the OED) is used to describe that which is attractive in a pretty or endearing way, then it follows that the primary objective of designing a cute object is to make it non-threatening enough for the user to protect and look after it.10 The affect engendered by cuteness is not random or undetermined, but pertains to a positive anthropomorphism deliberately controlled and aligned with commercial imperatives, as commented by Gary Genosko:

Commercial concerns always threaten to remake the cute body, to make it communicate and circulate more intensely through the transfer, extension, and diminishment of particular attributes, giving everyone a chance to be a kind of nurturer through consumption.11

In this sense, the design of the cute object is not predicated on a straightforward construction of the subject as a consumer despite the underlying commercial imperative. Rather, cuteness is directed towards the development of a “nurturing” consumer, whereby the latter’s acquisition of the object is arguably translated into a form of fetishism that elicits an affectionate form of control. Hence, the relationship between the subject and the cute object also highlights a difference of power, whereby an active subject exerts direct control over a passive, vulnerable object. This difference is power is in turn, reflected in the deformed, yet anthropomorphized appearance of the cute object. As described by Sianne Ngai:

For in addition to being a minor aesthetic concept that is fundamentally about minorness (in a way that, for instance, the concept of the glamorous is not), it is crucial to cuteness that its diminutive object has some sort of imposed-upon aspect or mien—that is, that it bears the look of an object not only formed but all too easily de-formed under the pressure of the subject’s feeling or attitude towards it.12

If cute is construed as a simulation, it is also a simulation that repeats a particular differentiation between the subject and object. With this artificiality—or perhaps more specifically, artificial deformity—cuteness not only erases any uncanny familiarity in anthropomorphism, but also serves to render a sterilized object that innocuously reflects the subject’s control and even mutilation on the object. Ngai aptly remarks that the aesthetic of cute points to an aphetic paradox, for while in other cases a shortened word would not lose its initial meaning, cute (as an aphaeresis of acute) “exemplifies a situation in which making a word smaller, more compact…results in an uncanny reversal, changing its meaning into its exact opposite.”13 In other words, this reversal can be understood as a form of de-verbalization that further reduces the object’s capacity for retaliation.

Given this basis, cute design is not simply a means to make the object non-threatening, but to effectively control and even pre-determine the subject-object relation. While it is agreed that love both online and offline is essentially interactive, I also contend that the former (as expressed in technologies like the dating sim) occurs within a space of controlled interactivity, not just with respect to how one can, but also who or what can be loved. Perhaps the question that one should ask is not about how love may be transformed in the context of the dating sim, but how the latter brings about a play of signifiers that allude to, but represent a love that is absent. By way of explanation, I do not intend to think of the attachment to the digital character in the dating sim as a form of paraphilia whereby any cute object can be substituted for a human lover. Rather, I maintain that the design and development of the cute character is both parallel to and compatible with the software architecture of the dating sim, and that this compatibility relies on a play of elements that writes off love’s absence rather than its differentiation.

Affective Systems

As mentioned earlier, dating sims are populated with numerous cute characters, synthesized through a repetition of style while seemingly differentiated by a surface narrative. Digitalization has certainly enhanced the systematization of cute design, but in reference to Hiroki Azuma’s observations on otaku culture, I would broadly highlight two features that have enabled cuteness to be applied as a computable system. There is firstly the production and distribution of “derivative works,” a term for the re-interpretation of original works by fan communities.14 In Japan, doujin games are video games made by hobby groups using existing characters in official ACG (animation, comics and games) works. Despite the fact that they are a violation of copyright laws, licensed producers do not frequently take legal action against them because these works—in fostering a more active fan community—indirectly contribute to the popularity and sale of the originals.

Still, fan prosumption aided by digital techniques and social networking sites continues to blur the difference between the original and the copy. According to Jean Baudrillard, the pervasiveness of this intermediary situation, where an object is no longer an exact original or copy is characteristic of the simulacrum or “process of simulation”:

A model is “built” by combining features or elements of reality, and an event, a structure or a future situation is “played out on” those elements, and tactical conclusions are drawn from this with which to operate on reality.15

In contrast with the creation of “original” content, the “model” Baudrillard mentions functions as a system that determines the type of goods and meaning that go into circulation. In the ACG industries, processes of production and consumption assume a bilateral pattern when fans eventually become licensed producers, or when the latter get to be involved in fan-derivative work. This instability in the status of a “fan” and “creator” also means that various design principles are less the unique property of a single creator than a collective of aesthetics emerging from a communicative, cultural space. Cute design in particular, is neither the result of a single creator, nor despite its relative nuances, an aesthetic exclusive to a particular culture. Rather I argue that its repeatability across a broad spectrum of cultural products shows that it is structurally like a language, with its intrinsic grammar and vocabulary. It is this linguistic dimension that undermines the authenticity of the cute object, for the category of “cute” is neither derived from nor applied to a single object, but can be used on other objects that adopt similar features.

The effacement of the distinction between original and copy is also connected to the second characteristic, which is the space of fiction afforded by the aesthetic. Commenting on otaku culture, Azuma claims that parallel to such an effacement is the decline of “value standards of social reality,” which is a reflection of the loss of a grand narrative. The otaku Azuma explains, are distinctively postmodern, because their immersion in the fiction of anime, manga, and related paraphernalia such as dating sims does not point to the presence of an overarching belief system, but the use of simulacra (or what Baudrillard would refer to as “features or elements of reality”) to construct their own beliefs.16

Hence sans the game mechanics, the difference or affection of the dating sim lies in its fictional contents and what these contents represent. On that note, cuteness is not just a part of the dating sim’s fiction, but is a design principle that is asymmetrical to biological morphology because of the fiction’s aesthetic and commercial concerns.

At the same time, however, these concerns do not suggest greater semantic flexibility, but are becoming systematized to the extent that certain variations of cuteness are made more visible than others. By way of explanation, a system is to be contrasted with open-ended units containing disconnected or differential properties. In the words of Ian Bogost, systems “seek to explain things in an unanlienable order,” whereby phenomena are explained and expected to comply with a static, immutable order. The concept of a system, Bogost goes on to explain, can be understood as structures controlled by rules that are pre-defined before a particular event is actualized.17 As opposed to a system that is defined only in relation to the specific and perhaps singular arrangement of its elements, the commercialization of cuteness in platforms like the dating sim indicates a move towards systems that are fixed according to factors of market demand.

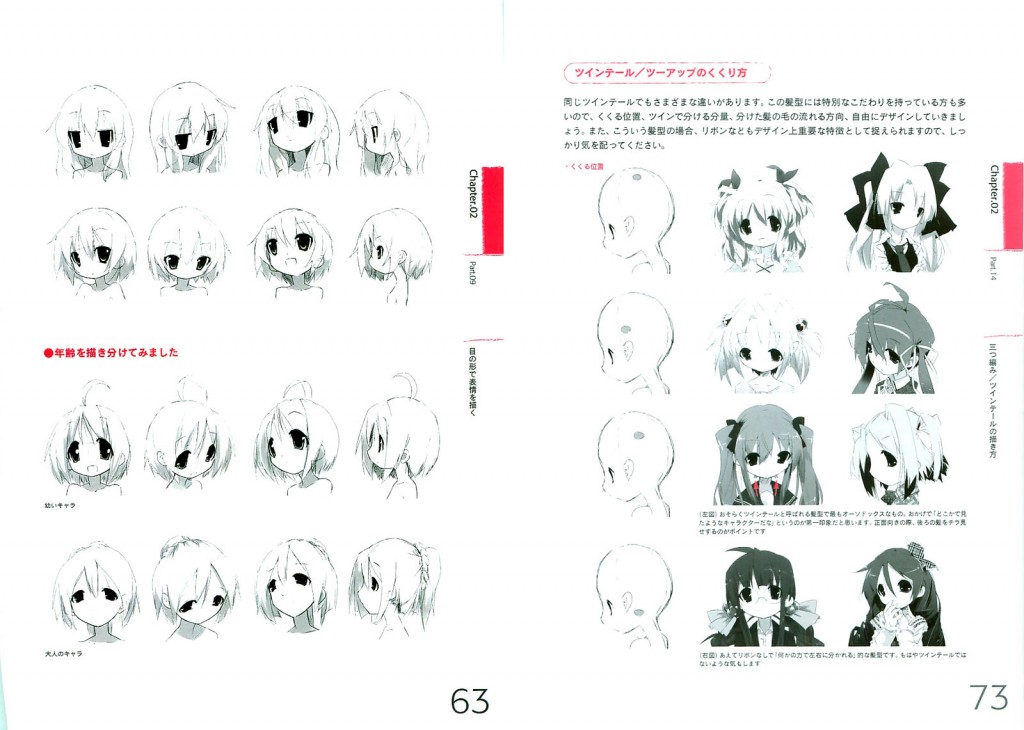

Azuma does not specifically compare or differentiate between the versions of cuteness, but he provides a detailed analysis of how one variant known as moe (萌) has been extensively systematized into a database that is used to develop dating sims and other ACG products. With the disintegration of a grand narrative, products have no independent value; that is they are not judged by a standard of “originality” but are assessed for their conformity to this particular database, or what in other terms could be regarded as “style.” Figure 3 below provides more details on how moe is applied in character design, by showing how a particular form of visual grammar (notably the shapes and proportions of the face and the eyes) can be repeated across different characters.

Figure 3: Facial compositions for moe characters (Source: “How to draw better moe characters” by Kamiyoshi, Kuroba and Shiratama Dango, Publisher: Seibundo Shinkosha)

Building on these largely hand-drawn images, the Kisekae Set System or KiSS is a non-commercial freeware program that allows users to customize their own animated characters by using preset features or elements such as apparel and accessories [Fig. 4]. Although Azuma does not explicitly discuss this in his conceptualization of the database, I note that the KiSS program exemplifies this systematization of elements that has become an important factor with respect to the design of characters in ACG products. As opposed to drawing or animating a character from scratch, each data set in the KiSS program comes with pre-designed elements that users can play and mix with other elements from other data sets. Users with the relevant technical expertise can also contribute to the KiSS database by designing and programming their own or editing other users’ data sets.

Figure 4: Screenshot of KiSS system with all interchangeable items in a data set (Source provided by author)

The function of the KiSS doll is for the most part ornamental; besides looking cute, most of the characters lack the level of interactivity and animation most dating sims afford. However, the interchangeability between elements of varying data sets underscores a basic formalization of cuteness that not only compromises the distinction between original and copy, but renders these simulacra, or copies without an original as repeatable units of information observable across various media. Once a particular feature (e.g. facial composition, voice, clothing, accessory) is accepted by producers and consumers as “cute,” it becomes incorporated into what Azuma would call a “database” of elements that can be accessed and re-mixed by anyone who intends to design or animate a cute character. These units or elements, according to Azuma are not individual unique designs that are attributed to one or a few individuals, but are an “output generated from preregistered elements and combined according to the marketing program of each work.”18 Indeed, the use of such a database spares very little room for creators to express their own interests, especially if these interests are not in agreement with what was initially systematized.

Hence for most content creators of dating sims, it is not the originality of the narrative, but the input and arrangement of various elements like character design and world settings that are of major concern. I also argue that “narratives” are in a way, structured together by these units of simulacra, which paradoxically are also traces of these narratives. So as opposed to greater flexibility in what could be classified as cute, the integration of the aesthetic into such a system implies the lovable is not de-territorialized, but made more recognizable through the machinery of a system. Azuma’s object analysis is therefore an application of the theories of Baudrillard, who writes:

[Simulation] … is a question of substituting the signs of the real for the real, that is to say of an operation deterring every real process via its operational double, a programmatic, metastable, perfectly descriptive machine that offers all the signs of the real and short-circuits all its vicissitudes.19

Baudrillard’s use of the term “machine” deserves further consideration, for Azuma’s database theory fits Baudrillard’s description squarely by demonstrating that cuteness as an instantiation of the lovable is no less technological than the interactivity of the lovers’ discourse. Moreover, cuteness can be understood as a technology that displaces the primacy of any meta-narrative by way of its virtualization, or potential to be copied and differentiated. One can also claim that the dating sim and all other character-based goods implicate an open-source aesthetics, where anyone who comprehends the given code or database may use it to produce similar work.

Given their ubiquity and extensive use in the development of ACG characters, cute elements certainly elude any exclusive claim of originality. However, their increased systematization as a visual language also means that cuteness—in describing the lovable—already pre-determines the conditions for what, or who can be loved. In other words, one does not come to love the cute object, but that the cute object is a thing that has to be loved. This pre-determination opens a space for us to examine the link between cuteness and the pursuit of love in its own absence.

Machine-Based Traces

To recapitulate, the difference that enables the dating sim to affect the player is a technological difference and this affection implies a form of interactivity, which according to Pettman is based on a cybernetic program. This program, it should be noted, positions the sender and the receiver as co-producers of meaning, for the sender does not simply compose and transmit the message, but is also sensitive to and responds accordingly to the feedback from the receiver. More importantly the positions of the sender and receiver are not discrete, but interchangeable variables, which is to say that they are structured and determined by their difference that materializes through the interaction.

The basis for such an approach treats culture as a linguistic construct and an outcome of technology, where “culture” in this instance involves the structure of language embedded in all forms of cultural production, including popular media like film, animation, and even video games. Hence, the cute object in more abstract terms is no less a written object than the words on a page, for it communicates the idea of the lovable even though the sender or original love object is not present. In the case of the dating sims, these in-game characters are but representations of the player’s beloved brought about by a system that names, orders and designates the positions of sender and receiver; of subject and object. Also, this positioning again involves a systematization of the lovable, displacing it from an experience of the interaction to that which is pre-determined, ordered and exploitable prior to any interaction.

As an artificial entity, the cute character in the dating sim is indeed virtualized as information that is repeated, but not differentiated in experience. This is because the systematization of cuteness as a design principle pre-determines the object’s difference and ensures the presentation of an identical image to every player. Despite the fact that cute elements are used to construct what would evidently be an endless variety of characters, their repeated visibility is not only a negation of the original, but to a more significant extent, bears witness to a complete erasure of originality itself.

Moreover, if we follow Azuma’s argument that there is no a priori cute object but only simulacra (copies with no originals), then the synthesis of an already simulated object and its subsequent reproducibility in digital form means that players are engaged in a repetition without differentiation. As Bernard Stiegler posits, “Information is not, in principle, repeatable: its repetition is an exhaustion of its value, as opposed to knowledge which, in principle, must be repeated and can never be exhausted through repetition…repetition exhausts information’s difference.”20

With regards to the systematization of cuteness, it seems to me that this particular synthesis of the lovable in the dating sim is a means to regulate, but not transform the ways in which love can be creatively played out. The technology of the lovable is fundamentally different from the interactivity of love, because the lovable comes before and hence forecloses the possibilities of such an interaction. Rather than think of love as a connection to the other and the mutual, on-going transformation of different individuals, the player of the dating sim bears more semblance to a romance addict who not only indulges in the repetition of play, but is also fascinated with the fiction of symbolic expressions because it is “easier to predict and control and does not involve real commitment or real change.”21 This repetition then points to a pursuit of the lovable in the absence of love, for although the lovable is made to represent love, it is by definition not an authentication of it. In other words, inasmuch as this play with simulacra pre-determines and repeats what or who can be loved, it nonetheless only deprives the subject of the object alluded to. As Baudrillard remarks, “Somewhere there is a “remainder”, which the subject cannot lay hold of, which he believes he can overcome by profusion, by accumulation, and which in the end merely puts more and more obstacles in the way of relating.”22

To reiterate, the avid player of the dating sim may not be much different from the romance addict, for the latter does not fall in love with anyone, but merely indulges in the process of acquiring the object of his or her pursuit. And while the cute character sets out to represent the beloved, it also signifies—as a remainder—the pursuit for a love lost, for in its pre-determination as simulation, it communicates the lovable in the absence of an authentic love object. Yet, if there is no love object to begin with, what remains for the player to pursue? Could the cute character in the dating sim be said to have charted a course that is apart from the interactivity of love?

Ludic Objects

In Azuma’s point of view, consumers of cute objects display desire without any form of inter-subjectivity. That is, the love for the cute object is not conceived as an outcome of an interaction, for the object is built to understand and display love in a certain way. Dating sims, for Azuma, can be viewed as a form of gratification symptomatic of the commodification of desire, because “objects of desire that could not be had without social communication such as everyday meals and sexual partners, can now be obtained very easily.”23 Consumers, in particular the otaku, adopt a more “animalistic” approach to satisfying their desires, by consuming such objects without any tangible regard for the other.

As such, this particular programmability of desire contains an important difference between the interactivity between two enamored lovers and the experience of the dating sim, but there is a need to refrain from making a direct connection between the consumption of a cute object to the desire for physical connection. To have an interest or to be attached to these cute objects is not necessarily a result of an addictive mis-recognition and to claim that these objects can be treated as immediate substitutes for a living companion would be to overlook their consumption as objects of fiction. If the otaku, as Azuma understands them, are able to distinguish between fiction and “reality,” then it is equally necessary to understand how such a fiction may specifically exert a material force different from a fetish object in “reality” that gratifies a desire anterior to consumption.

Dialogue options and digital characters are arguably two important features within the fiction of the dating sim, given that they serve as conductors for content that would eventually structure the narrative. As such, these two features can be regarded as subsets or “directories” within Azuma’s larger database of elements. However, these features are not without ambiguity, for while they can be programmed in an arbitrary fashion that would lead to variations in the storyline, they are also aggregates of minor elements that are increasingly standardized. In other words, there is a dynamic potential, insofar as the placing of a certain dialogue option or the insertion of a character may lead to a development of alternative narratives and value judgements, but as described earlier, there is likewise a pervasive pre-determination with respect to the contents and style of these features.

The consequent tension is thus due to the relationship between units and systems. For theorists like Bogost, such dynamism is characteristic of unit operations, which he defines as “modes of meaning-making that privilege discrete, disconnected actions over deterministic, progressive systems.”24 For Bogost, unit operations are essentially variables of difference that are played across all modes of cultural consumption and production. To think of video games, and in particular dating sims as objects built and systematized from unit operations is to re-direct the emphasis from homogenous, rule-based systems to a complex network that derives meaning from the “interrelations of components.”25 Extending Bogost’s propositions to the dating sim, it becomes possible to conceive of the fiction in dating sims as a system that effectively plays with the signifiers of a romantic relationship, without actualizing the experience of a “real” romance or instantiating a substitute for a human partner.

However, I would argue it is this very same notion of play that not only differentiates and thereby nullifies the romantic experience, but also repeats the systematization of the lovable in turn. This repetition, I contend is not simply restricted to the pre-determination of the dialogue options, but is to a significant extent, concerned with the play of elements that make up the cuteness of the in-game character. Although character design can be considered a unit operation, the concretization of various styles like cute point instead to a reaffirmation of systematicity in which the synthesis of the lovable is far from an open-ended actualization. The play that undergirds consumption is therefore not a subversive differentiation of a love object, but a movement denoting its absence. So while cuteness refers to a meta-template of visual features and personality traits that can be played without any finality, I insist that this play is neither a strict manifestation of a perverted desire, nor an uncontrollable and irrational addiction to consumption.

Rather, this play is of a ludic nature, where one is drawn to and enmeshed in this “cybernetic absorption of play.”26 That is, the lovable becomes part of a playable process that fascinates, but indeed falls short in bringing about an authentic experience of love. Cybernetic absorption then, is not just in reference to the interactivity of the dating sim’s mechanics, but also about the surface effects of the cute character amplified by the tangibility of such an interaction.

In my view, this amplification complements the interface of dating sims but at the same time reveals a few problems. There is, in a matter of appearance, the artificiality of cuteness that renders it a positive form of anthropomorphism. As mentioned before, these characters are not in any way a replication of the human body. Instead, they are simultaneously a caricatured deformation of the biological form and a humanized animation of an artificial, non-living object. In other words, the cute character is not a straightforward humanization of the other, but a humanization brought forth vis-à-vis an inherent dehumanization of artificiality. To be lovable or brought close to their human partners, the bodies of cute characters are designed to be clean and child-like, without any biological features associated with excrement or aggression. This, I maintain is how the ludic is complicit with the condition of the lovable, in which play rationalizes all possible outcomes. In the words of Baudrillard: “The ludic encompasses all the different ways one can “play” with networks, not in order to establish alternatives, but to discover their state of optimal functioning.”27

And it is according to this particular rationality of surface effects that cute characters are rendered as passive objects in the interface of the dating sim, for even as they appear onscreen like an object to be pursued, these characters are in turn framed or distanced as targets to be controlled and acquired. This distancing to quote Paul Virilio, pertains to a “defeat of the fact of making love” brought about by the distance of the image, which means that the extent of control over the object is antithetical to the intimacy one can experience with it.28 An irreparable distance thus underlies the lovable, for as the condition that is determined and designed in advance, it undermines the agency of and indefinitely denies the consummation between one and the other.

Hence in this particular game of love, the cute character is not the subject of agency, but an object rigorously manipulated and determined by the preferences of its consumer market. This manipulation is similarly extended to the systematization of cute design; by fragmenting, or reducing the aesthetic of cute into individual, interchangeable units, producers can easily develop different characters and settings to make the dating sim re-playable and repeatable across a broad spectrum of narratives. As a result, there is no need for players to be attached to one character, for they can either play a different character within the same, or another game.

Given this basis, the use of cute characters in the dating sim works against the transformative effects of the lovers’ discourse, because this representation of the lovable is constructed before love is played out or experienced. Such a pre-determination does not mean that players will never be attracted to, or fall in love within the cute character; rather I argue that all interactivity with the dating sim is driven by an illusion of agency on the part of the user. Even as players are free to select any of the options in the game’s narrative, they are neither able to create, nor alter the effects of their selections. In addition, the object of their pursuit is not a singular, distinct other, but a designed permutation derived from a system of characteristics and features that have come to be qualified as “cute.”

In that sense, what largely transpires from such an interaction is not mutual affection, but a technological fascination where users who in being complicit with these technologies, can only encounter themselves in the technology. Since it is eventually manufactured as software, the cute character may affect but is not at all affected, for its difference has been fully incorporated within a determined technical system. And as far as the gameplay is concerned, players’ inputs do not translate into a creative transformative moment, for the corresponding results of all possible selections are already delimited and exhausted by both the design system and the software architecture.

These technological interventions in the dating sim lead to a “one-sided” affair, as love is less an emergent interactive experience than it is a pre-determined and manufactured commodity. Yet to be on one side does not imply that one’s affections are not reciprocated, but that such affections are self-reciprocated. The direct control over a technical object like the cute character of a dating sim, is in Marshall McLuhan’s words an “autoamputation”29 or direct extension of ourselves, for like the myth of Narcissus, the character in the dating sim only reflects the results of our own inputs. The circuit is thus a “narcissistic” one,30 since it fascinates the pursuer not with the beloved, but simply with the pursuit in the game itself. In this digitalization of the lovers’ discourse, love becomes that which the player brings into the game, which means that the encounter with the beloved—insofar as the beloved is regarded as a co-creator of meaning with the lover in the cybernetic loop—is never attained, but effectively delayed.

Conclusion: Absence as Presence

If it is established that the adjective of cute belongs to the domain of the lovable, would it be a quality of a thing, or a response of one who is affected by it? This interminable relationship between cuteness and love calls attention to the question of naming in absence, because if the lover calls unto the beloved, how can one know if that is what the beloved is, or a declaration of the lover’s love? As profoundly described by Jacques Derrida:

…when I call you my love, is it that I am calling you, yourself, or is it that I am telling my love? and when I tell you my love is it that I am declaring my love to you or indeed that I am telling you, yourself my love, and that you are my love. I want so much to tell you.31

The lack of a proper designation for the lover’s claim and the claim of the beloved resonates with the condition of the lovable as simulation. When a player interacts with a cute character, is the character indeed the beloved, or is the beloved made absent by the program? The complexities of this question I note, clearly point to the absence of that which is pursued, for if there was a finality that could be known or made present, then this pursuit would end with cuteness arriving at its appropriate place of understanding. Derrida, however, claims that such a message never arrives, for the very act of writing and interpretation is the possibility of a different reading, of differing and deferring. In the same fashion, the lovable is not able to account for or be an absolute message or substitute for what love is, since it is a fixed abstraction and hence simulation of a dynamic process. Cuteness as a systematization of the lovable may only simulate love’s difference, thus leaving one, at best, to express the longing for love in the object of the lovable. The continuous proliferation of cute characters and the concretization of their features are not simply ways of representing the beloved, but also an example demonstrating that the lovable is an unfinished pursuit of the beloved.

To further connect Derrida’s views with the dating sim, it can be argued that the interactivity of the latter is haunted by the presence of the cute character, which via artificiality, is no less a trace of a love recognized through its own loss. I use the term “haunted” to refer to the affective presence of cuteness and its effects as simulation, because the cute character, by alluding to a love that is not, is similar to a haunted situation that continues to affect, even when the thing itself is absent. With its visibility on the dating sim’s interface, the cute character elicits a non-physical presence that simulates, but fails to replicate the proximity of a real-life partner. In immersing themselves in the fiction of the game, players are tangibly affected by the character’s presence even if this presence is not connected to an actual person. This shows that any cute object, despite being entirely artificial, can still affect because it re-traces sentiments initially expressed in subject-object relations, thus showing that cuteness can evoke a presence founded on absence.

The film Her (directed by Spike Jonze) offers an alternative view of how the fascination with the medium can to some extent be mistaken for the presence of the other. An intelligent operating system named Samantha is able to converse with and adapt to the human Theodore, but this adaptation begins when she responds in a manner that is pleasing only to him. Arguably the “love” that ensues between man and the feminized machine here is also a personalized projection, for Samantha is only able to unreservedly reciprocate Theodore’s affections based on the information she gathers from and about him. Samantha becomes more self-aware and at one point desires to acquire a physical body for Theodore, but it is Theodore who persistently mistakes the medium or operating system of “Samantha” for the tangible presence of a significant other.

Hence Theodore’s love for Samantha is not a simple misrecognition, but a calculated and pre-determined substitute for a mutually transformative encounter. Although Samantha’s in-built curiosity allows her intelligence to develop and evolve, her eventual self-erasure is an example of the lack of a mutually shared finality or telos that can direct and curtail her own development. Ontologically speaking, she is but the means and not the end to the love that Theodore yearns for. Samantha’s absolute sense of self-awareness eventually sets her apart from Theodore and her isolation as an object leaves her without any objective, just as how a tool no longer in use may no longer be regarded as such. And while the lack of a face and a body serves to highlight the software construct of Samantha as communication tool, the cute character in the dating sim completely humanizes the technology with these features. By endowing the lovable with a face and body, the cute character returns the condition of the lovable back to us, by synthesizing not just a voice, but also an anthropomorphic image in the interaction.

The technological reification of cuteness and its subsequent integration with other consumer objects present a critical issue for the increasingly technological milieu: The desire to not encounter the other, but an image of ourselves that can only affect us through the standardization of an idealized difference. As I have argued, cuteness is premised on the systematization and mastery of the lovable as an object different from us, of selectively exorcising the undesirable and thereby precluding the possibilities that are realized when confronted with what is neither known, nor subjected to control.

My position therefore is not a direct refutation of what could be a de-territorialized concept of love, wherein the love object is constantly differentiated through technological innovation. Rather, I conclude that along with the change in the metaphors, there are also corresponding spaces of control whereby love can be represented and hence toyed with. Cute design is no less technological than a software program and as the dating sim clearly illustrates, it is in this expression of the lovable that love is visibly absent, insofar as the combinatorial remediation of love’s symbolic expressions and the lovable work together to pre-determine and not differentiate the object of one’s affections.

So it is in the artificiality of the cute object that the determination of the lovable negates the possibility of love. This is because as a factitious image, the cute character is manufactured from a system that both orders and fragments the notion of cute into repeatable, interchangeable elements, which are in turn, applied onto design templates in the relevant cultural industries. To set down beforehand what can be loved is not a pursuit of the beloved with all its unknown possibilities, but to achieve a mastery of the pursuit itself. It is in this mastery that the problem of mistaking one’s own enunciation for an attribute of the beloved resurfaces, for even though cuteness is attractive, it is no less a structure that is increasingly rationalized along consumer imperatives of self-gratification.

This is why for some, cuteness may no longer be an attribute of the beloved, but simply a disembodied signifier playfully consumed. As this inquiry has explained, the attraction of the dating sim is not specifically based on the interactivity of the game mechanics, but together with the design of the in-game characters, denotes an almost insular structure built to translate and return the results of players’ inputs. To play with the lovable is not quite the same as the play between two lovers, for in its own systematization the lovable may prove to yet be a prosaic freeze-frame of an experience that continues to re-write the rules of its own game. Yet, it is in the reproducibility of these objects and the various characteristics that have come to be understood as “cute,” that all that is longed for can be continuously pursued but never completely attained. We will of course, find a way to love; but as cuteness has made clear there will always be the condition(s) of the lovable to lead us astray.

- The “conclusion” here need not necessarily refer to a particular scene that brings the game to a close, as some dating sims are organized around daily experiences in cyclical time (e.g. LovePlus). Regardless of whether this conclusion takes the form of narrative closure or otherwise, such differences do not negate the primary aim of “being together” with the in-game character. ↩

- Otaku is a Japanese slang term referring to avid consumers of animation, comics and games (ACG). While I acknowledge the majority of otaku are adult males, it is not the aim of this article to focus on a particular mode of consumption as observed within a selected demographic. The structural implications of dating sims I am considering here are not restricted to games targeted at any specific gender or social group. Rather, they are an example of a pre-determined condition of love that is remediated, and “played out” via a certain technological apparatus. ↩

- W. David Marx, “The Love Plus Scourge takes another life: Man ‘marries’ video game” CNN Travel (2005) http://travel.cnn.com/tokyo/none/love-plus-scourge-takes-another-life-man-marries-video-game-687520 (accessed 25 March 2013). ↩

- Dominic Pettman, “Love in the Time of Tamagotchi,” Theory, Culture & Society, 26.2-3 (2009), 190. ↩

- Although this article seems to focus on the problem of romantic love (eros) as presented and experienced in the dating sim, I do not intend to render a precise definition of love, or attempt to differentiate erotic love from other concepts such as storge, philia or agape. However, I will use the representation of eros in the dating sim to question the connection to otherness that all expressions of love allude to. ↩

- Niklas Luhmann, Love: A Sketch (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2010), 6. ↩

- Benedict Spinoza, Ethics (London: Wordsworth, 2001), 111. ↩

- Gilles Deleuze, Difference and Repetition (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994), 209. ↩

- Pierre Lévy, Becoming Virtual: Reality in the Digital Age (New York: Plenum Press, 1998), 26. ↩

- The link between the current definition of cute and the lovable is not explicit in English, but the equivalent of cute in other East Asian languages (particularly Japanese) shares a distinct etymological relationship with love. The Japanese word for cute, or kawaii (可愛い) contains the kanji character for love and both these kanji characters in the Japanese are adjectives borrowed from the Chinese which is exactly translated as “lovable” or “that which can be loved.” ↩

- Gary Genosko, “Natures and Cultures of Cuteness,” Invisible Culture: An Electronic Journal for Visual Culture, 9 (2005), http://www.rochester.edu/in_visible_culture/Issue_9/genosko.html (accessed 1 December 2013). ↩

- Sianne Ngai, “The Cuteness of the Avant-Garde,” Critical Inquiry, 31.4 (2005), 816. ↩

- Ngai, “The Cuteness” 827. ↩

- Hiroki Azuma, Otaku: Japan’s Database Animals (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009), 25. ↩

- Jean Baudrillard, The Consumer Society: Myths and Structures (London: Sage, 1994), 126. ↩

- Azuma, Otaku, 27. ↩

- Ian Bogost, Unit Operations: An Approach to Video Game Criticism (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 2006), 7. ↩

- Azuma, Otaku, 42. ↩

- Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation (Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 1994), 3. ↩

- Bernard Stiegler, Technics and Time 2: Disorientation (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2009), 137. ↩

- Ralph D. Ellis, Eros in a Narcissistic Culture (London: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1996), 158. ↩

- Jean Baudrillard, Passwords (London & New York: Verso, 2003), 5. ↩

- Azuma, Otaku, 87. ↩

- Bogost, Unit Operations, 3. ↩

- Bogost, Unit, 4. ↩

- Jean Baudrillard, Seduction (New York: St Martin’s Press, 1990), 159. ↩

- Baudrillard, Seduction, 158. ↩

- Paul Virilio, Open Sky (London: Verso, 1997), 113. ↩

- Marshall McLuhan, Understanding the Media: The Extensions of Man (London: Routledge, 2001), 46. ↩

- I capture this term within quotation marks to dispute the notion that an attachment to the digital partner is an expression of narcissism as a psychological disorder. The condition of narcissism here is aligned with McLuhan’s understanding of technology as an auto-affective device that is an extension of the human. ↩

- Jacques Derrida, The Postcard: From Socrates to Freud and Beyond (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), 8. ↩