By heidi andrea restrepo rhodes

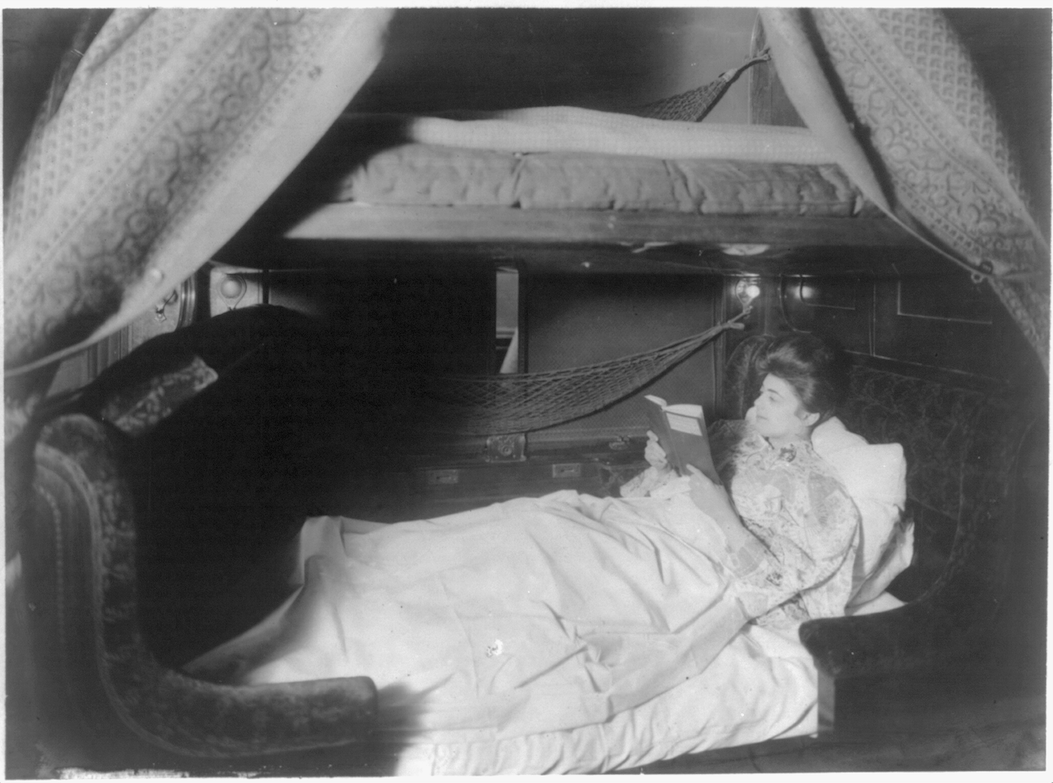

Featured image: “Lady reading in berth with curtains down,” Geo. R. Lawrence Co., c. 1905, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The Brooklyn-based project, Rest for Resistance centers rest as crucial to healing work (it is so much work to heal!), bridging the vital importance of psychological and social support; and of individual and collective wellness for marginalized communities, including “Black, Indigenous, Latinx, Pacific Islander, Asian, Middle Eastern, and multiracial persons” and “LGBTQIA+ …trans & queer people of color, as well as other stigmatized groups such as sex workers, immigrants, persons with physical and/or mental disabilities, and those living at the intersections of all of the above.”1 Published by QTPOC Mental Health, a community justice initiative, the Rest for Resistance Zine features writing and photography that foreground rest as a deeply political activity. In Juhee Kwon’s piece, “We Are Not Machines”, Kwon reminds us that “we’re more complicated than a simple input (x) à output (y) kind of linear function”—questioning the correlations between overworking one’s self and how “success” is measured through whether and how we’ve maximized our productivity. At the expense of our physical and mental health.2

The exhibit Black Power Naps by multi-media artists and activists niv Acosta and (Fannie) Sosa (January 9-31, 2019, Performance Space New York) constructed an installation of a comfortable, restful space where people of color could show up to simply rest, reclaiming laziness and idleness as deeply political expressions of power.

To quote the project’s mission statement:

“Departing from historical records that show that deliberate fragmentation of restorative sleep patterns were used to subjugate and extract labor from enslaved people, we have realized that this extraction has not stopped, it has only morphed.

A state of constant fatigue is still used to break our will. This “sleep gap” shows that there are front lines in our bedrooms as well as the streets: deficit of sleep and lack of free time for some is the building block of the “free world”. After learning who benefits most from restful sleep and down time, we are creating interactive surfaces for a playful approach to investigate and practice deliberate energetic repair.

As Afro Latinx artists, we believe that reparation must come from the institution under many shapes, one of them being the redistribution of rest, relaxation, and down times.”3

The poignancy of this installation’s architecture rendered available specifically for downtime for people of color inside the “city that never sleeps” is also not lost on me. If what me and Tala, as chronically sick queer non-black femmes of color are calling “bedlife” is the insistence that bedboundedness is not deathboundedness but an onto-epistemological set of differences that make possible practices of world-building; this exhibit highlights how life is made possible in and by the bed as a location symbolizing the possibility of rest: how the differential distribution of bedtimes, and time in bed, is a racially-configured violence in a political economy and national spirit founded on anti-blackness and slavery. Of black life in the wake, and black life awake.4 How “quality sleep is really only given to rich, white people” and how the hustle has been glorified through US-American individualism that ignores the racist conditions on which our notions of independence and dependency have been constituted, while white institutions economize on the struggles of people of color. The connections between chronic violence, chronic illnesses that disproportionately affect black, indigenous, and people of color, and the structuring of work’s chronicity (the long work day, the lack of vacation, the non-stop of emotional labor of contending with racism), must be attended to. Black Power Naps takes this up, noting too, how rest’s threat to the order of things is a vital part of liberatory endeavor: that fully rested, fully self-possessed black life is, to quote niv Acosta, “the white man’s worst nightmare.”5

Rest is a cultivated absence, the choreography of the body’s collapse. A wrench in Capitalism’s droving of laboring bodies like robot machines of endless supply. Rest, like poetry, is not escape or luxury or relinquishing political life and accountability to the world.6 Can rest be a reorientation toward modes of being that refuse the infinite sourcing of extraction? We view rest as political indeed, an evasion of what Jasbir Puar has called “liberal eugenics of lifestyle programming” to which we are subject in its intensifications of neoliberal marketization of everything in existence.7 Under this neo-eugenic programming, every action and interaction, every word spoken, every expression of the body, every minute of every day, should be geared toward symbolic and material profit. This is how we are told to measure our value, whether or not we’ve lived up to the “well-born” as a constant and perpetual bootstraps birthing of ourselves into a wellness that is meant to function only and precisely for the grind of capitalism’s wheel in ever-expanding profit. Rest refuses the totalizing hold of this economy on the body that is struggling to flourish in its own fleshly ruins wrought by the vicissitudes of capital’s legacy — of total depletion, toxicity, and annihilative violence. Rest is preservation of individual and collective selves for a radical and undisciplined wellness; and destruction of industry as a compulsory and natural law. Rest is the reclined and purposeful disinclination to capital’s insistence on our orientation toward the incline. Not limited to the bed and its reclinations, rest is also playfulness, the reach for pleasure and expressions of want outside of and away from the commodification of our bodies as perpetual and simultaneously configured labor, product, and marketplace.

***

This post is excerpted with permission from the section titled “rest” in Tala Khanmalek and Heidi Andrea Restrepo Rhodes, “A Decolonial Feminist Epistemology of the Bed: A Compendium Incomplete of Sick and Disabled Queer Brown Femme Bodies of Knowledge,” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 41, no. 1 (2020): 35-58. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/755339.

Header image: Geo R. Lawrence Co., Lady reading in berth with curtains down, c. 1905.

- Rest for Resistance, QTPOC Mental Health, https://restforresistance.com/ (accessed January 1, 2019). ↩

- Juhee Kwon, “We Are Not Machines,” in Rest for Resistance Zine, ed. Dom Chatterjee, Kofi Opam, and OAO, (QTPOC Mental Health, 2017), 4-5. ↩

- niv Acosta and Fanny Sosa, Black Power Naps, https://blackpowernaps.black/ (accessed January 1, 2019). ↩

- Black life “in the wake” references Christina Sharpe’s notion of the wake as the total climate of anti-blackness in the afterlives of slavery. Through the brilliance of Acosta and Sosa’s Black Power Naps, we can also read the chronic lack of sleep for black people—the over-extension of working hours as waking hours—as another manifestation of slavery’s wake. See Sharpe, Christina, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016). ↩

- niv Acosta, quoted in Michael Love Michael, “If You’re Black, Rest is Power,” Paper Magazine, http://www.papermag.com/black-power-naps-2626998633.html (accessed January 1, 2019). ↩

- See Audre Lorde, “Poetry is Not A Luxury” in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Freedom: The Crossing Press, 1984), 37-39. ↩

- See Jasbir K. Puar, “Coda: The Cost of Getting Better: Suicide, Sensation, Switchpoints,” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, 18, no. 1 (2012): 149-158. ↩