by Sarah Friedland and Tess Takahashi

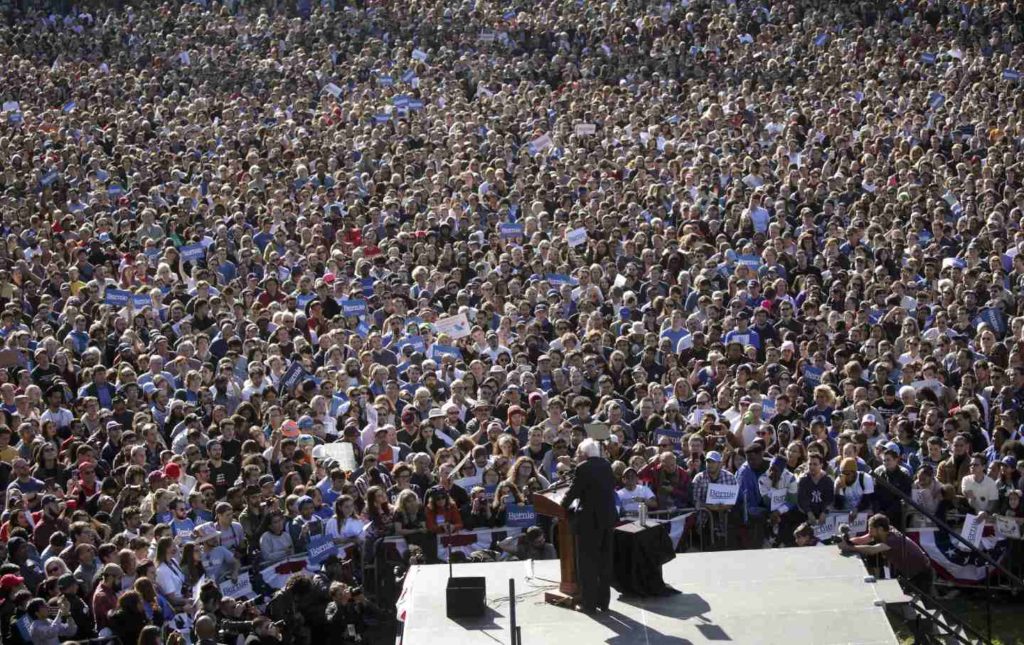

Featured Image: Still from Sarah Friedland, CROWDS, Channel 1.

Curator’s note by Almudena Escobar López:

Sarah Friedland and Tess Takahashi have been in dialogue since they met at the “moving.media@brown” conference in 2016, where they realized that both share an ongoing interest in patterns of movement and their connection with larger cultural formations. As Sarah Friedland and I were working on the development of the exhibition Assembled Choreographies at the Hartnett Gallery (March 29 through April 26, 2021), and thinking about its translation to an online environment, we decided to include a consolidated version of her conversations with Takahashi.

The exhibition centered on the visual language of movement, the typology of the crowd, and the process of how bodies learn from each other. It included a virtual installation of CROWDS (2019) and a screening of Drills (2020) and Home Exercises (2017). CROWDS’ digital interface was designed by Friedland in collaboration with media artist and designer Jonas Eltes, translating the 3-channel installation for an online audience. The CROWDS website opened with “A Score for Distant Viewing” that acknowledged the embodiment of mediated viewing, and closed with “Murmurations,” whose original zigzag format is mimicked here.

The discussion focuses on the choreography of the crowd and its visualization. Friedland discusses her production and research process for her three-channel installation CROWDS, in connection with Takahashi’s research around murmuring and data visualization. The conversation then moves to the political ramifications of the visual language of the crowd in connection with the recent events that took place on January 6, 2021 at the Capitol.

***

This text assembles, excerpts, and condenses our conversations from the last four years of being interlocutors.

Murmuration

Tess Takahashi: You and I were at a conference and I learned that you were also a mover, as well as a filmmaker and a thinker. We were both thinking about murmuration, like the starling murmurations that you see on YouTube with birds flying in incredible patterns, but for different reasons. You were thinking about the phenomenon of murmuration in relation to CROWDS when you were looking at lots of images online, and thinking about both the grammars of crowds and their representation as you got ready to head to Italy to work on the film during a residency. I recently learned that starlings murmurate in response to a predator, like a hawk or an eagle. That’s not something you usually look for in the frame, but very often a much larger bird is visible. Thinking about murmuration as a tactic in response to threat got me thinking about crowds of people, whether in a protest or in terms of how they were represented in data visualization, which I have been working on.

I’d been thinking about the movement of starling murmurations in relation to murmuring as a form of vocal protest for weak or vulnerable human subjects. The murmur is figured as more of a continuous vibration than a sound object. Even more so than Mladen Dolar’s examples of the prelinguistic voice (such as the child’s cry, the cough, the hiccup, and the scream), a murmur is indistinct, blurry, and continuous.1 Rather than a sharp, differentiated, identifiable sound, the murmur suggests temporal continuity and potential endlessness, coming in the form of a “hum, humming, buzz, buzzing, thrum, thrumming, drone, sigh, rustle.”

You were also thinking about starling murmuration, but specifically in relation to gesture and the physical movement of crowds.

Sarah Friedland: My first encounter with murmuration, and the initial inspiration for this project, was about 25 years ago, as a kid living in Italy. There are these starlings that murmurate over Fiumicino airport in Rome that I used to see. I think what fascinated me about them is that they have this nonhierarchical structure in which there is no decay in the transmission of information. If you’re looking at the edge of the flock, it’s just as precise in its coherence to the bodies around it as the middle. It appears as if it’s constantly folding in on itself; at any point that you look at it and see its form, it mutates again. So it never really reaches this static place, which was how I was thinking about the structure of CROWDS’ choreography: of constant folds, slips, and mutations in the choreographic identity of the crowd so that it never reaches stasis.

I’ve been thinking about your idea of murmuration as continuous vibration and am curious how we might think about the safety enabled through embodied or choreographic murmuration. How might continuous vibration be happening in the dance studio, as a relay of information between dancers with minimal decay? Dance scholars, such as Erin Brannigan, who was my mentor and had a big influence on my work, have written about forms of “gestural exchange” between dancing bodies.2 Many of the vibratory exchanges occurring between dancers happen too simultaneously and quickly to see its staged progression in real time. I wonder if information lag or decay is also reduced in crowds because the bodies entering into them know the choreographies expected of them. Coming into the crowd don’t we already know the moves we’re going to do?

In CROWDS’ rehearsals, we contended with these shared, already-known rules and logics that aid the synchronous emergence of movement within a crowd. Until I read your article, in which you describe the murmur as “an almost unintelligible utterance,” I didn’t realize one of the other ways I was thinking through this project and its relation to murmuration: part of my intent was to bring a group of people together to try and utter what the choreographic language of crowds might be. Because its coding and grammar is not readily apparent to most of us. It’s so ubiquitous, yet so rarely named or deconstructed. And so the space of the dance studio was where we could attempt and practice that utterance without the pressure of immediate legibility.

Takahashi: In terms of voice, as it relates to your practice, I had started thinking about murmurs as vocal articulations that at first seem nonsensical or illegible. Even if a murmur isn’t speech in the way we usually think of it, a murmur is a kind of vibratory communication, for example between a parent and child or between lovers. In those contexts, a murmur communicates presence and intimacy. But then, I was also thinking about what a murmur could communicate in public space, in relationship to various kinds of crowds. There’s the distracted public murmur of the coffee house, but that’s of little consequence. What about where there’s more at stake? If you have a single voice raised in protest, that person stands out and is more at risk. But if you have a number of people murmuring, saying the same thing, or saying things to each other, it’s much more difficult to pin down. This kind of murmur can become more public, operating like gossip or a rumor, something initially said cautiously and discretely, as in “they began to murmur of an uprising.” Here, the murmur of discontent has an object. Maybe it’s directed at others who are unhappy, or maybe it’s directed to the state itself. In the case of public protest, the murmur’s lack of a distinct origin can be a protective strategy for those discontented subjects.

In terms of legibility, I’ve been thinking about how, after the Hong Kong government outlawed literal signs with protest speech on them, protesters would hold up blank sheets of paper and cardboard en masse.

Friedland: I was listening to an interview with some Hong Kong protesters who shared the motto they repeat to one another which translates as “never sever ties” or “no cutting of ties,” referring to their collective agreement to not break their unity, even if positions over tactics differ. In a way, these words reflect the logic of murmuration, and flocking patterns in general: each must remain connected to the next and reproduce its movement; group coherence and flow is dependent upon individual movement. Which is manifest in the “flocking” exercise used in Viewpoints theater practice, which we used as a sort of container for our own improvisation within the studio in which we would articulate a set of rules or logics that the dancers would adhere to before slowly loosening, mutating, and breaking them. In thinking through the strategies of those protests, the motto “never sever ties” also articulates the choreographic logic that enables a group of people to occupy public space and be present with one another. It’s a description of politics as a collective, kinesthetic relationship. It reminds me of André Lapecki’s essay on choreopolitics in which he describes “imagining and enacting a politics of movement as a choreopolitics of freedom.”3

Takahashi: That makes me think of Adriana Cavarero, who talks about the political possibility when bodies are in the same space when they speak to each other. For Cavarero, whether articulate or not, the voice is distinctly human, in that it references the materiality and individuality of the body from which it is emitted. Cavarero insists that the literal expression of embodied voices revealing their uniqueness in proximity to one another functions as a charged moment of political possibility.4 There’s something very compelling about speaking in physical proximity to others and their bodies in a crowd. In many cases, it is important to be together in a place physically as opposed to just registering your presence digitally.

That said, being together physically in a crowd of protest always has at least two audiences. The first time that I’d ever been part of a crowd marching in protest (versus marching in a parade carrying a clarinet in a high school band) I remember wondering how much of our gathering together physically was for the purpose of authorities seeing us together en masse—and how much was for us in terms of being together, walking together through the streets, chanting, clapping, and marching together.

Friedland: In my rehearsals with the dancers, it was also important for us to play with certain rhythms of speech and clapping, both in terms of how they influence the body, but also how they can shape the sense of time and rhythm within the crowd. For example, while we were rehearsing there were independence protests happening in Catalunya in which there was this escalating clapping pattern that kept being reproduced in documentation. I shared this footage and clapping pattern with the dancers and some of the Italians in the room were immediately like, “No, no, no. In Italy we do it like this.” And they shared with us the anti-war clapping pattern from protests they had been to, which rhythmically accompanies the words “Noi la guerra non la vogliamo,” meaning “we don’t want the war.” And then everyone started sharing different clapping patterns from protests that they had been in, which started fusing together. The clapping became a way of coming together around a certain rhythm, but it also offered the opportunity for escalation. This is indicative of how we worked, bringing in found movement and rhythms from protests we had been in or seen, that began to cross-pollinate.

Language and Codes: Gestures and Views

Takahashi: Can you talk more about your process of choreographing CROWDS? Part of what you seem to be doing in taking apart the gestures of crowds is asking questions about how a shift in gesture works to change the kind of crowd it is, say from a march to a protest to a riot. What are arms and legs doing? What’s their tone, their slackness? How are they connected to the rest of the body’s posture, to the speed of its locomotion?

In your choreography, you also seem to be thinking about if and how the gestures of crowds can be separated from a particular context and intention—and then stitched back together to evoke those historical moments. How do those gestures travel through time and across space—both through representation and in our very bodies? How do those gestures operate in other historical moments, or in the service of other ideologies?

Friedland: In the process of choreographing, I engaged two archives simultaneously. First, there were the embodied memories of the dancers and myself, and second, there was the moving image documentation of crowds we had not been in. It felt important to put these two archives into contact with one another, through the movement and performance of our bodies where, inevitably, these two sources of crowd choreography intermingle and co-determine what we know as the choreographic language of crowds. This choreography, when enacted or articulated, draws on both sources, complicating their distinguishability.

I’ve been influenced by the writing of dance scholar Susan Leigh Foster, who writes about the idea of kinesthetic empathy. That, due to the mirror neurons in our brains, we replicate the movement we see in our own bodies. When watching dance we “dance along” even if our bodies remain outwardly still.5 If we take this idea seriously, then there is a physical trace—an embodied memory—of every image we have seen documenting crowds we have not been in.

This was clearly evident in the rehearsal process. When I would ask the dancers how a certain type of crowd moved, they could elaborate its choreography with great ease and proficiency, irregardless of their past participation. This doesn’t resolve the complicated ethics of working with found movement—one friend challenged me, asking why I thought it was okay to “extract” movement from experiences and histories not my own. However, this phenomenon of knowing in our bodies something we’ve only seen complicates the bounds of embodied memory and experience.

There’s a way in which our bodies feel like they know the choreography of experiences that are not ours, including choreographies of violence. In a way, I wanted to try and address the problematic choreographic knowledge that our bodies have, that don’t belong to us yet are present. What is it that our bodies know about these collective and crowd experiences, both of historically specific moments, and of broader categories or types of crowd events and identities, such as congregations, riots, protests, etc.? What is invoked when our bodies have an understanding of a choreography without past physical experience?

Takahashi: I was also thinking about CROWDS as a choreography that references the gestures of crowds, takes them out of context, and reorganizes them. At the same time, your choreography of gestures invokes the situations from which they emerged, whether it’s a funeral procession or military procession, for example. There’s both a clear structure to CROWDS, and an inherent instability because the gestures you incorporate are always in flux, moving from one thing to another so that the gesture doesn’t always become recognizable through repetition. Since each gesture is always in the process of becoming something else, your morphing crowd doesn’t always have a legible identity. That’s a really interesting tension in the piece—the tension between structure and flow, clarity and illegibility. Additionally, it seems like the points of view through which you shoot your crowd of dancers, whether long shot or close up, really changes what becomes legible to a viewer at different moments.

Friedland: One of the sources of clarity and structure is the reproduction in CROWDS of repeated views from documentation of crowds: of the bird’s eye view, the face in the crowd, and what I had been calling on our shotlist the “sideline” view. A big part of my research was tracking not only the choreography of crowds, but the cinematographic tropes and frames that are repeated in their documentation. I’m fascinated by the fact that representations of contemporary protests rely upon similar cinematography as fascist propaganda, particularly in their use of the overhead shot, also known as the bird’s eye or god’s eye view. That shot of the crowd, whose prototype we see in Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will, is used for populist documentation on both the left and right.

During and after Bernie Sanders’ 2019 rally in Queens, an overhead image of the large crowd was continually reposted with phrases such as “we’re gonna win.” The unspoken logic of this shot is that in its wideness you can see the sheer number of people present—the masses—who are visible from this perspective. At a glance, they evidence the will of the people. What’s interesting, though, is that this perspective is usually impossible for most individuals to access without a drone or helicopter. And this comes back to your work on the anxieties of loss in representations of magnitude: when you are in a crowd, you are aware of this overhead perspective that you don’t actually have access to in the moment. You know you are part of its magnitude. What is the significance of the shared appeal of this viewpoint for both fascist propaganda, big data, and left-wing populism?

Takahashi: This is an age in which political action often occurs at a distance rather than in physical proximity. I wondered how we might think about the ways those murmuring “voices” of protest travel across various forms of mediation, like email, text, images, and phone? And, as you say, today there’s both a real faith in vast numbers as giving evidence of the truth, on the one hand, and seeing something with your own eyes, on the other hand. The bird’s eye view seems to invoke the all-at-once view of data visualization’s vast numbers and the hand-held shot makes you feel as if you’re there, at least by proxy.

Friedland: The allure of the overhead shot is also replicated from an adjacent angle. In the many mass protest movements we’ve seen globally in recent years, cell phone footage shot from rooftops, balconies, and windows often shares the logic of the bird’s eye view, even if not quite reaching the extremity of angle and height—of god. Last year, one of the dancers I worked with, who is from Chile, sent me videos shot by protesters which included a shot from a high window like this and it still succeeds in speaking to the numbers and mass body of the crowd. I’ve seen similar shots in cell phone footage posted on twitter and facebook from Beirut, Hong Kong, Haiti, Belarus, and Puerto Rico, among others. And in these shots I do feel both that sense of proxy, because of the hand-held, cell phone footage, and the all-at-once-ness of it, because of the angle. And I think we saw the duality of those two views in the videos of Black Lives Matter protests that circulated this summer.

Headcounts, data, and the aesthetics of epistemology

Friedland: Your essay on data visualization really spoke to me because I think the wide, overhead shot operates similarly to the data visualization you’re writing about. You write of the magnitude of data visualization as offering “the illusion of immediate knowing.” There’s a similar allure to the wide overhead shot.

Takahashi: Yes, data visualization seems to “speak to the eye.” It has an epistemologically calming effect, making us feel as if we’ve mastered the otherwise unwieldy mass of information generated about the big world. The crowd points to the specificity of individual numbers and individual voices that comprise it, but the crowd can also speak with the single voice. Data visualization, like the overhead shot, produces an illusion of wholeness: it strives to contain its own unstable, often ignored, desirous voices through the power of visual abstractions, an abstraction that turns messy specificities into neat numbers, clear lines, and bright colors. Graphic forms of data visualization produce some of the most coherent, authoritative, and “audible” arguments about the world today.

Despite data visualization’s illusion of wholeness and certainty, like the overhead drone shot of the crowd, it can efface the individual textures of the horde of embodied human perspectives that it claims to represent. What of those voices, those perspectives? While it’s imperative to amalgamate data in order to render a multiplicity of voices singular, data visualization inevitably points to a disparate range of individual experiences. How then, can this emphasis on multiplicity shift the way we understand individual “testimony?”

Friedland: The cliché of the “face in the crowd,” enacted usually through a close-up shot with a long lens through which the other faces fade out of focus, visually claims that individual testimony. Yet from the perspective of the overhead shot you see both that the crowd’s composed of many bodies, and also the emergence of a unified crowd body. Part of the desire for the bird’s eye view is its production of a headcount. From above, heads become individual data points.

Takahashi: The head is like a dot.

Friedland: Exactly. And part of the efficacy of the fascist salute is that even from above, you see the clarity of that arm. So you get both the sense of a singular voice and its testimony in the unique performance of the gesture (how high is the arm? How straight is the elbow? etcetera) and the compression to a dot, providing evidence of a unified mentality en masse. I think there’s something about the straight line of the arm, the directionality of the gesture, that fortifies the headcount.

Takahashi: It’s a vector. It’s a moving vector that would be a strong contrast to the point of the head when shot from above. It’s interesting that one could also say that about the Black Power Fist, which would be visible from any angle, whether overhead or straight on. Both the Nazi Salute and the Black Power Fist suggest a directional political unity amongst the crowd in the sense that it lets you know what they stand for immediately. Such gestures also make it easier to count individuals. One of the things about numbers is they make democracy possible because they allow people to communicate at distances. At the same time, numbers inspire the fear of becoming only a number or losing one’s individuality.

Friedland: And that’s where John Durham Peters’ link between counting and numbers in democracy really clicked for me: “Numbers in all their impersonality are democracy’s ideal language, suited for gods, machines, and collectives.”6 Part of why I think this shot is continually reproduced in documenting progressive and pro-democracy protests is that, in this moment of rising authoritarianism and neo-fascism, the headcount provides evidence of democratic and populist power. There’s a comforting contrast for the liberal and anti-fascist imaginations, and perhaps also, such as in the case of Bernie’s rally documentation, a direct speaking back to Trump’s obsession with crowd numbers. In 2016, a split screen image was widely disseminated showing the lackluster crowds at Trump’s inauguration in comparison with the massive turnout of Obama’s.

Takahashi: When Trump’s falsification of the numbers at his inauguration became public, senior advisor Kellyanne Conway told Chuck Todd on Sunday’s Meet the Press that he wasn’t lying. He was simply giving “alternative facts.” In 2016, the year in which Trump was elected, the Oxford dictionary word of the year was “post-truth.” Throughout the beginning of the Twenty-first Century, politicians increasingly seemed to choose amongst the many facts available and select those they deemed most useful for their own agendas. We have seen the dismissal of “inconvenient facts” under the Bush administration in 2004 and the introduction of “alternative facts” under the Trump administration in 2017 conveniently employed to steer policy, cut funds, and start wars. But, as you say, the overhead photographic view of those crowds shows the truth of things.

Friedland: Stand-ins have featured prominently in both Trump’s election campaign and presidency: background actors hired and paid to perform as individuals within the crowd. When the extra or stand-in is cast to be in a crowd that we know will be shot from above, they are, in a way, being cast in order to be transformed, immediately, into a data point within the visual headcount. It further affirms the performative nature of data visualization as enacted by the crowd. I’m really interested in the history of extras and stand-ins and the labor they perform, something I’m starting to research for a new installation project.

Takahashi: Data visualization can be a kind of stand-in. I mean this in the sense that data visualization is linked to a particular form of indexicality, in which sensors read elements of the material world and translate them into numbers that stand in for material objects and bodies. The evidentiary force of indexicality comes from both the image’s likeness to that thing in the world and the idea that it was indeed “there then” when the image was taken. In the case of the background actors cast as stand-ins to fill out Trump’s campaign crowds, the image indexes their bodies there in the crowd. They’re really standing there, but in standing-in for Trump supporters, they’re false representations. They show us how images and numbers need context to be read correctly.

Friedland: In the most recent inauguration we saw a different kind of stand-in present in the crowds, once again witnessed from above. The space previously occupied by the crowds of January 6th and of the prior two inaugurations, was transformed into a “Field of Flags” filled with 200,000 flags meant to represent those that might have attended the inauguration were there not a pandemic.

Yet to my eyes it appeared not as a stand-in for a crowd of joyous Biden fans, but as a grossly inadequate stand-in and data visualization for the American lives lost to COVID-19. I was immediately reminded of images of Arlington Cemetery, where there is a tradition called “Flag-ins” in which a flag is placed in front of every grave before Memorial Day: mini-flags stand upright in parallel lines to the vertical tombstones, aligned in an endless grid of graves. At Arlington, each flag represents a single, dead soldier. At the inauguration, each flag represented an American who could have contributed to Biden’s headcount, obscuring the body count it inadvertently invoked and conjuring up a speculative fiction of the overflowing masses attesting to Biden’s popular and electoral mandate.

What’s interesting about the scale and ratio of this field is that each flag is meant in this case to represent one person, and yet the American flag is already a graphic and representational compression: a data reduction that segments the population by state (stars) and former British colony (stripes). It speaks to the current state of American nationalism that this object of state power, which graphically maps American colonialism and imperialism, and which functions as a symbol of white nationalism, became an unintentional stand-in for the individual citizens whom the state failed to care for.

In attempting to invoke the power of the headcount, Biden’s administration unwittingly fabricated an under-enumerated graveyard; the flags were less than half the count of those who had died of COVID-19 by inauguration day. If we see this Field as such, the identical flags present a false equivalency, as if to suggest we have all been impacted equally by COVID, as if the dead aren’t disproportionately Black, Brown, Indigenous, old, disabled, and poor.

Takahashi: That’s true. Rather than the specificity of individual lives lost, bodies displayed, and the grief of suffering loved ones, the misrecognition of flags for bodies impacted by COVID-19 is a productive misrecognition that reveals the structure of violence of governmental policies around the virus. Rather than the overwhelming emotion of melodrama, which you have with individual stories and bodies, these flags as data visualizations produce a powerful view of the larger cultural field. At the same time, that overhead view can allow us to distance ourselves, to stand apart.

Friedland: That feeling of distance is part of how I conceptualized the 2nd channel, which is what I called on set our “sideline” view. One of the main logics of crowds, Elias Canetti argues, is that once you enter, there’s an attraction towards one another to fill in and close all spaces between yourself and the other bodies.7 I kept seeing shots in my research that might be varied in framing style, but that all hovered right at the edge of the crowd, at the periphery between where you’re a spectator and a participant, on the verge of giving into that pull or attraction to being surrounded by the crowd that Canetti writes of, and the safety of distance. It’s an invisible threshold. But remaining in the space between is untenable. So the idea behind the second channel—a tracking shot slowly wrapping around the circumference of the piazza—is to place the viewer at the place where they have to make a choice between visual access and participation.

My intention for the installation design’s effect was that you’d experience the agency to move between perspectives, while also carrying the knowledge of loss. In moving in between the three channels you will not, and cannot, see everything. You can never access a totalizing view of the crowd. And so your body enacts the edit between shots, screens, and points of view, in such a way that you have to contend with the privileges and disadvantages of each perspective.

Takahashi: The question of loss applies to every form of representation. This is especially true for data visualization, which leaves out so much in order to be immediately graspable, immediately comprehensible. Critics of data visualization often turn to the phenomenological as an antidote to this loss of experience. However, part of what your piece shows us is that all views are partial. All views incorporate loss in our encounters with them. The impossibility of seeing all three screens at once stages a scene of productive frustration.

Elizabeth Cowie writes in regards to expansive time-based documentary installations in the gallery, the multi-hour temporality of time-based installation tends to evoke frustration and anxiety in the spectator. However, as Cowie notes, this “experience of incompleteness…—is itself an achievement of the artwork.”8

Friedland: I think the viewers’ movement between the channels is motivated by trying to escape the anxieties of loss that you write about; by moving in between the channels, viewers act out the fantasy that we might be able to see everything.

postscript 1.6.21: the stakes of reading crowds

Takahashi: Why is it important to consider both how crowds operate and how we read them? In part, it’s important because we need to think about how we understand crowds and their politics—and recently, it feels like there are increased stakes to reading the choreography of crowds. For example, does a Bernie Sanders rally look different from a Trump rally from overhead? From the ground? What about crowds of protest? What about the strangeness of the right-wing protests on January 6th at the Capitol?

Friedland: I think the events of January 6th—the crowd’s slippery choreography and the discursive crisis of naming them and their actions—were a really pointed example of what’s at stake. Watching multiple news channels that afternoon, a common refrain amongst commentators was “Why is no one stopping them?” There was an expectation of arrest. But this expectation not only reflected their anticipation of greater law enforcement presence and the full force of the carceral state we live in, but of a literal arrest, in the sense of putting a stop to that crowd’s movement that we would expect such a presence to produce. In our embodied and visual memories from watching other protests’ documentation, or from being in them, we recall these moments where their motion is arrested by law enforcement. Individuals are immobilized, detained, pushed back, and too often harmed in the process. However, on January 6th, unarrested in their forward motion, this crowd had the space-time to keep moving and keep mutating, shifting in form. With the agency to be mutable, they enacted multiple crowd choreographies, each signifying a different crowd type or identity.

This is a big part of the reason there was a crisis around naming them and what they were doing. I say “part”, because, of course, the naming and typologizing of crowds is not merely a choreographic task. It is raced, gendered, classed, and informed by so many other discourses. They kept mutating as a crowd, slipping between looking like rioters, tourists, carnival revelers, a lynch mob, congregants, and several other corps identities. The disparate choreographies they took up made it impossible for the crowd to be legible as a single type. On Twitter, I watched dozens of videos circulating on the 6th and in the days that followed. By watching and privileging any one of these videos’ perspectives over another, you would name a different crowd type.

In our conversation a few weeks ago, a day or two after January 6th, I remarked that I saw the day as a violent carnival rather than a coup, as it was still being called by major news outlets at the time. You brought in Bakhtin to our conversation and his idea of the carnivalesque.

Takahashi: Bakhtin describes the carnivalesque as set apart from the order of everyday life and turning that order upside down.9 It’s anti-elitist, a popular celebration of the bodily, the vulgar, the humorous, and the nonsensical. Carnival is seen as inherently bringing together opposites, like birth and death, high and low. It’s also seen as both revolutionary, and as staving off revolution.

Friedland: To give one example of the coming together of opposites on January 6th: in one video a man in military gear performs a circular gesture repeatedly to usher people inside with a “go, go, go!” vocal directive. His gesture reads as part of a military siege or invasion. And yet with the frat-like quality of those entering beside him, I couldn’t help but think of the trope within teen party movies where news of a supposed-to-be-just-a-few-friends party leaks and the unsuspecting host opens the door to a flood of raucous non-friends.

It isn’t hard to reconcile the visions of white fraternal raucousness with the more explicitly violent acts witnessed on the 6th, such as the brutal crushing and beating of officers and the pursuit of Eugene Goodman, a Black Capitol police officer, by a mob of white men. The former is not innocent. The casual excesses of white leisure have always been violent, in their racism, in their misogyny, in their imperialism, in their xenophobia. The cavorting we see in one video of that day isn’t at odds with the gruesomeness of another, but rather twinned behaviors of the same crowd. Another expression of this was the proximity of the prayer circle that formed to the looting of the halls and offices of Congress. Congregants become looting rioters. These contrasts—in tone, behavior, affect—show how white raucousness permits itself the fiction of freedom and fun as an alibi for violence.

Takahashi: The slipperyness of this crowd’s form has made it difficult for most pundits to talk about why it was so upsetting. However, that sense of unease remains.

Friedland: I feel like this crowd actually embodied what I most fear in a crowd and tried to manufacture for CROWDS. That is, the January 6th crowd was so slippery it defied a moment of static legibility that might permit typologizing, one that disallows our discursive debates to catch up in time to make sense of it. One that constantly re-forms, and reshapes, to fit its goals. This is what terrifies me most about the crowd of 1.6.21: the mutable and chameleonic quality of their movement and ambulation that allows them to pass through undetected. Of course, much has already been written about how their whiteness allowed them to pass through into the building, but it wasn’t only that. They showed how easily the prayer circle can become the lynch mob. And I think this is actually at odds with many popular perceptions of crowds and why we fear them.

I’ve heard a lot of people’s fears about crowds over the last four years of working on this project. I think one of the most common is still colored by the pop-psychology of people like Gustave Le Bon, of fearing the erasure of individuality amidst the overtaking of mob mentality. You might lose yourself, their fears say. I don’t fear losing myself; I fear the unrecognized violence of mutation and the slow slips into a crowd that has yet to be named. Perhaps my fear stems from the intense emphasis on Holocaust memorialization (and singularization) in the education of my generation of American Jews. We were taught to recognize the destructive mob of Kristallnacht as a precursor to the gestapo and SS. And therefore received in the messaging of “never again” this propensity for identification, which is, of course, so tied to naming. As if to suggest, if you spot (and name) the fascist crowd in its infancy you might escape or prevent its fully genocidal form. This crowd of 1.6.21, that we were unable to collectively name, performed this mutation par excellence. And as we continue to debate its name, it will continue to mutate, reshaping without detection.

***

Sarah Friedland is a filmmaker and choreographer working at the intersection of moving images and moving bodies. Her work has been screened, installed, and performed across film, art, and dance venues including New York Film Festival, New Directors/New Films, Ann Arbor Film Festival, BAMcinématek, Performa19 Biennial, La MaMa Galleria, Sharjah Art Foundation, MAM Rio, the American Dance Festival and Dixon Place, among many others. She most recently completed the AIM Emerging Artist Fellowship at The Bronx Museum.

Tess Takahashi is a Toronto-based scholar, writer, and programmer who focuses on experimental moving image arts. She is currently working on two books, Impure Film: Medium Specificity and the North American Avant-Garde (1968-2008), which examines artists’ work with historically new media, and On Magnitude, which considers artists’ work against the scale of big data. She is a member of the experimental media programming collective Ad Hoc and the editorial collective for Camera Obscura: Feminism, Culture, and Media. Takahashi’s writing has been published there as well as in Cinema Journal, the Millennium Film Journal, Animation, MIRAGE, and Cinema Scope.

- Mladen Dolar, A Voice and Nothing More (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2006). ↩

- Erin Brannigan, Dancefilm: Choreography and the Moving Image (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011). ↩

- André Lepecki, “Choreopolice and Choreopolitics: or, The Task of the Dancer,” TDR/The Drama Review 57, no. 4 (2013): 13-27. ↩

- Adriana Cavarero, For More than One Voice: Toward a Philosophy of Vocal Expression, trans. Paul A. Kottman (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005). ↩

- Susan Leigh Forster, Choreographing Empathy: Kinesthesia in Performance (Milton Park: Routledge, 2010). ↩

- John Durham Peters, “‘The Only Proper Scale of Representation:’ The Politics of Statistics and Stories,” Political Communication 18 (2001): 433-49. ↩

- Elias Canetti, Crowds and Power, trans. Carol Stewart (New York: Continuum, 1962). ↩

- Elizabeth Cowie, “On Documentary Sounds and Images in the Gallery,” Screen 50, no. 1 (2009): 133. ↩

- Mikhail Bakhtin, Problems of Dostoevky’s Poetics, trans. Caryl Emerson (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984). ↩