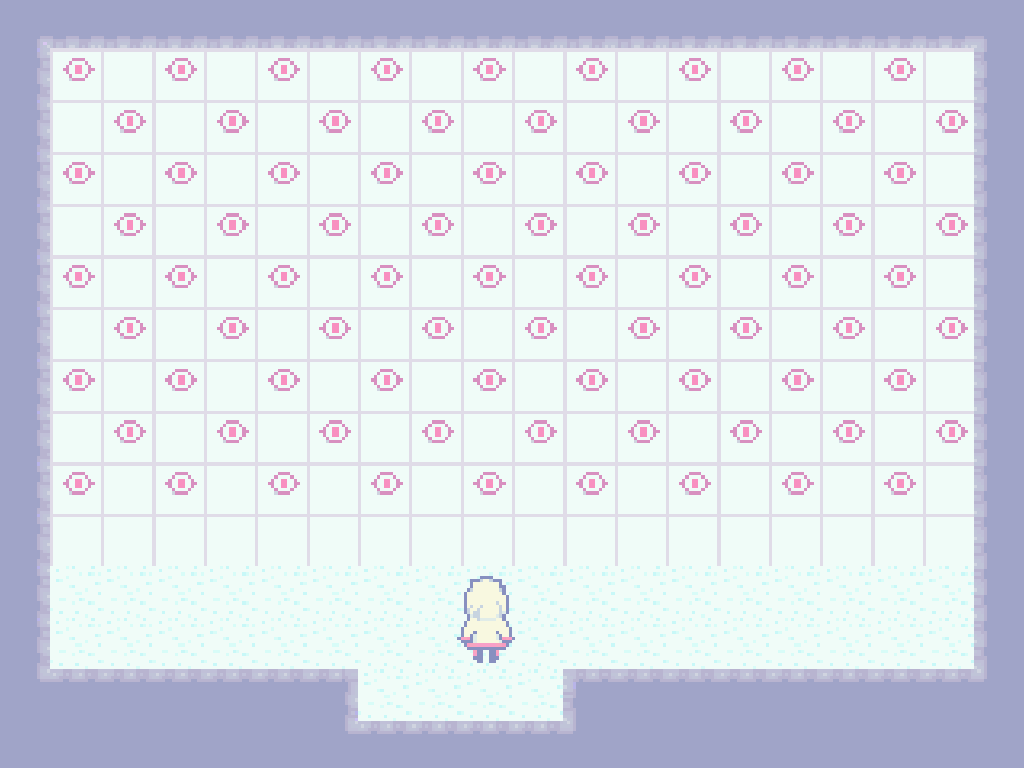

Artwork by contributor Iasmin Omar Ata.

For Issue 30, the editorial board of InVisible Culture is honored to present a special introduction by Dr. Aubrey Anable.

In my book, Playing with Feelings: Video Games and Affect, I make the claim that video games are the most significant art form of the twenty-first century.1 It was meant as a provocation and, by settling the matter, a call to move the discussion away from the question: are video games art? And toward the more interesting one: What do video game aesthetics do in the world now? This move takes its inspiration from Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s definition of “reparative reading.” Interrogating the critical habits in the humanities that keep us fixated on taxonomies, ontologies, and what they hide, Sedgwick compels us to instead ask, “What does knowledge do—the pursuit of it, the having and exposing of it, the receiving again of knowledge of what one already knows? How, in short, is knowledge performative, and how best does one move among its causes and effects?”2 Paraphrasing Sedgwick we might ask: How do video game aesthetics produce knowledge? How is this knowledge performatively made “across history, bodies, hardware, and code.”3 And how does one best navigate amongst the causes and effects of video games as expressive forms? The essays in this issue of InVisible Culture ask these and other questions. In doing so they contribute to the now well-established field of game studies, they also offer their own provocations to the field and to media studies, visual studies, and cultural studies more broadly.

Game studies emerged over the past twenty years. Initially, it was shaped by debates about the ontological status of “games” and a wariness about applying the methods of other humanistic disciplines to them. No longer wary, the new wave of scholarship on video games, of which these essays are a part, is defined by a commitment to radical interdisciplinarity and ontological promiscuity. Along the way, game studies scholars have produced genuinely original concepts and theoretical insights: the military-entertainment complex, procedural rhetoric, gamer theory, and the charmed circle of play, to name only a few.4 The new wave of game scholarship has been especially shaped by theories of embodiment, affect theory, critical race theory, and queer theory.5 There is still much to be done: on race, on spectatorship, on games and gaming beyond North America, Europe, and Japan, on decolonizing games, on disability, on trans frameworks for making and critiquing games, etc. All of this work needs also to attend to the lessons of visual and cultural studies: that video games are historically, discursively, and technologically linked to other media, art, and to culture more broadly.

But, what do video game aesthetics do in the world right now? For those who do not play video games (though most people do, perhaps without even realizing it, in some form or another) this may seem like an uninteresting or even frivolous question. In these times of multiplying and compounding political, humanitarian, and environmental crises, who has time to play, let alone think critically about, video games? How do the “Poetics of Play” speak to “Contending with Crisis,” the theme of another recent issue of InVisible Culture? In response to these questions, and to introduce some of the topics explored in this issue, I offer a few possible answers.

Video games make technocultural conditions perceptible—as in available to the senses and available to critique—in unique ways. Since their origin in Cold War computer labs, they have been the primary affective interface of personal computing. Besides learning from the fields I mention above, game studies also has lessons to teach these fields. Video games are sites through which to grasp the aesthetic and ideological shifts of the last few decades. They are digital spaces where our more mundane digital applications and their corresponding attitudes (email, social media, typing words into open Word document) are imbued with the possibilities of fantasy and play. They offer unique insights into how computers have transformed politics, emotions, sociality, and play over the last half century. As such, they have become the most significant space in culture both for a kind of aesthetic attunement to digital life and for important interventions and disruptions in the ways power works through digital systems. The essays in this issue attest to the new avenues that video games open in debates about realism, technology and embodiment, queer theory, posthumanism, time studies, affect theory, and pedagogy.

This issue’s insistence on poetics of play (rather than of games) compels us to hold acts of making together with acts of playing. Here, poiesis—making art, games, theory, and other possible futures—is fused to play,as part of the performance of meaning that any game, artwork, or theory makes. In the Practice of Everyday Life, Michel de Certeau argues that the ordinary activities of poiesis in life—making dinner, walking through the city, reading a book—“create…play in the machine” by making the rules and structures of these systems open to new possibilities.6

—Aubrey Anable, 2019.

Issue 30: Poetics of Play

Oscar Moralde’s “Wait Wait… Don’t Play Me: The Clicker Game Genre and Configuring Everyday Temporalities” investigates the link between video game genres, aesthetics of duration, and the temporalities of everyday life by examining a relatively young genre predominantly defined by duration: the clicker game, also known as the idle game or incremental game. The genre, whose primary gameplay consists of clicking to make a number go up and activating automated processes to make the number go up faster, was initiated by satirical and absurdist games such as Cow Clicker (2010) and Cookie Clicker (2013), but has been quickly followed by dozens of (mostly) sincere imitators. Discussion of the genre has focused on the seemingly-paradoxical popularity of games with little to no gameplay; however, I argue that the genre’s dominating aesthetic strategy is in recasting the act of waiting as a form of active gameplay through activating both very short durations (scattered momentary gameplay actions) and very long durations (the accumulation of those actions into progress over days, weeks, and months). To function, the clicker genre requires a technocultural environment where individuals have near-continuous access to computing power; in the ways that clicker games reshape temporality through those computing devices, they make visible a technocratic neoliberal logic of extracting value from ever more granular segments of time.

Grant Bollmer’s “The Kinesthetic Index: Videogames and the Body of Motion Capture” intertwines three themes: the inscription of human bodies in digital media, realism in digital animation, and the indexicality of kinesthetic traces produced through motion capture. It positions representation as reliant on material techniques of inscription through the examination of a transitional moment in the history of digital animation: the use of motion capture and video in the graphic adventure gaming genre. This history points to the emergence of a different sense of realism than either that of the photographic index or dismissals of computational simulation, one that relies on a kind of kinesthetic indexicality that does not inherently require visual verisimilitude. It depends the reperformance of “real bodies” through the technical extraction and encoding of gesture, and only indirectly appeals to the visual, though it provokes questions about the politics of representation and identity in games and digital animation.

Nicole Kurashige’s “Playful (Counter)Publics: Game Mods as Rhetorical Forms of Active and Subversive Player Participation” examines the limitations of procedural rhetoric and RPG generic conventions that downplay or ignore the historical, sociocultural, political, and/or economic realities that impact players outside the game. These issues are further exacerbated through rules that require players to conform to certain ideological norms if they want to “successfully” participate in the game. Procedural rhetoric, in this regard, is a double-edged sword in its educative yet interpellative capabilities. While commercial games leave little room to challenge such preconceived structures, fan-made modifications (colloquially known as “mods”) can be used to not only enhance entertainment, but also encourage players to interrogate their perpetuation of a particular system of beliefs. Pokémon Uranium (2016) and Pokémon Korosu (2016), two unofficial spin-offs of Nintendo’s Pokémon (1996–2017) series, are examples of how mods can be used to subvert the procedurality of the original games and create (counter)public discursive communities via online forums where players converge and collaborate. Understanding the motivation and use of mods as an active form of player resistance is, therefore, essential in unpacking the pedagogical potential that modding has as a subversive act against procedural rhetoric within gaming communities that serve as (counter)public discursive spheres.

In “The Monster Has Kind Eyes: Intimacy and Frustration in The Last Guardian,” Kaelan Doyle-Myerscough mobilizes affect theory and posthuman studies to consider how The Last Guardian creates intimate affects through frustration. In The Last Guardian, the player controls an unnamed boy who must befriend a giant gryphon-like creature named Trico in order to navigate a highly vertical ruined landscape. Doyle-Myerscough examines the formal qualities and affective capacities of Trico and the boy for their differing and yet supplementary frustrations, reads for the ways the two must move together through the highly vertical environment in which they find themselves, and considers how this verticality modulates the forms of frustration with which they must contend. Drawing from Donna Haraway’s notions of companion species and the oddkin, they argue that this frustration creates a complex form of intimacy between the boy, Trico, and the player.

Iasmin Omar Ata’s “Being” is an abstract adventure game that explores, from a future lens, the past and present of the Palestinian lived experience. The player controls an avatar from the distant future of Palestine on a mission to recover artifacts, memories, and messages from a mysterious house near an old border. The game’s aspiration is to convey various aspects of living as a Palestinian during the past century, ranging from perpetual grief to enduring hope.

Nilson Carroll’s “Untitled Dating Sim” considers the abstractions of human bodies in games as more than just a means to score points through (a patriarchal notion). Players follow the logic of visual novels to create the possibility for love/connection rather than a digital exchange between player and game aestheticized by violence. “Boy’s Curse/Boy’s Blessing” is an inversion of the idyllic experience of the dating sim. Whereas the sim is an exploration of tangible themes through everyday, mundane encounters, “Boy’s Curse/Boy’s Blessing” explores thoughts and questions that are far more ambiguous and uncomfortable.

- Aubrey Anable, Playing with Feelings: Video Games and Affect (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2018). ↩

- Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, “Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading, or You’re So Paranoid You Probably Think This Essay is About You,” Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003) 124. ↩

- Anable, Playing with Feelings, xi. ↩

- Tim Lenoir and Henry Lowood, “Theaters of War: The Military-Entertainment Complex,” 2002, http://www.stanford.edu/class/sts145/Library/Lenoir-Lowood_TheatersOfWar.pdf Ian Bogost, Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2007). McKenzie Wark, Gamer Theory (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007). Adrienne Shaw, “Circles, Charmed and Magic: Queering Game Studies,” QED: A Journal in GLBTQ Worldmaking, Volume 2, Number 2, Summer 2015, 64-97. ↩

- See for example Brendan Keogh, A Play of Bodies: How We Perceive Videogames (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2018), Gaming Representation: Race, Gender, and Sexuality in Video Games, edited by Jennifer Malkowski and TreaAndrea M. Russworm (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2017), Queer Game Studies, edited by Bonnie Ruberg and Adrienne Shaw (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017). ↩

- Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984) 30. ↩