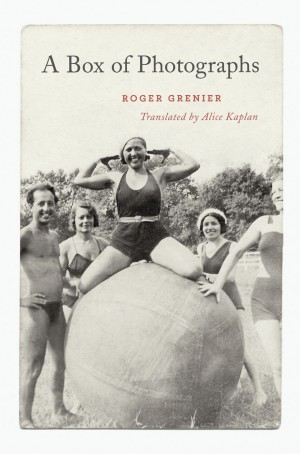

Roger Grenier. A Box of Photographs. Translated by Alice Kaplan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013. 109 pp.

In this slender volume, writer Roger Grenier shares a life well lived, rich in memories, friendship, and historical touchstones. The 95-year-old Man of Letters offers A Box of Photographs as recollection and examination of histories personal, global, and cultural, and photography serves as the North Star in the telling of his story.

Largely chronological, Grenier traces how photographs and cameras intersected with formative instances of his life. Using an economy of words in his vignettes—the shortest a slim paragraph, the longest several pages—he recounts the cameras he’s owned with the heartfelt fondness of someone reminiscing about an old love or a favorite haunt. For Grenier, this relationship began early. His parents were opticians and as a sideline to their business, they added a photo printing service. At age ten, he received his first camera, the 2 x 4½ Baby Box, a small handheld manufactured by Zeiss. In his later adventures, images and reflections are captured by an Agfa Box, a Kodak 6½ x 11, an Agfa 6 x9, a Voigtländer Reflex, and a Rolleicord, among others. Attendant to each of these devices are the stories, by turns elegant and sobering, of the events tethered to each.

Snap! There’s Grenier’s photograph of his sister Odette on the occasion of her first communion, the sunlight from a window caressing her face and the finery in which she’s adorned.

Click! Here’s the newsroom and staff of Combat, a French resistance newspaper. The bespectacled Grenier and the paper’s editor, Albert Camus, are celebrating New Year’s Eve along with the others.

Flash! A tuxedoed Grenier and Sophia Loren are dining in Cortina d’Ampezzo celebrating the Winter Olympics.

Pop! Here’s the estimable photographer Brassaï, Grenier’s longtime friend and confidante, convalescing in a Parisian hospital.

The stories and encounters with notables continue with the author, who has been awarded the Grand Prix de Littératur de l’Académie Française and has penned some thirty novels. The vignettes move from his grueling stints as a World War II soldier and participation in the Paris liberation, which nearly cost him his life, to less volatile scenarios, like an awkward encounter with Giselle Freund many years after she had made his portrait. In each case, the memory is tethered directly to a camera or a photograph. In other instances, he reflects on a host of other image makers’ thoughts about photography to further his own ideas, invoking an eclectic mix that includes Weegee, Diane Arbus, Julia Margaret Cameron, Alfred Eisenstaedt, Germaine Krull, and Inge Morath. In the book’s closing, he evocatively calls on Arbus’ succinct summation of photography: “A photograph is a secret about a secret.”

For his part, Grenier writes honestly and openly. His recollections are elegant and balanced between sweet (without becoming saccharine) and sobering and, at at all times, closely observed. Here, Grenier recalls an uncle whilst looking at his photograph: “Martha’s husband is wearing white gloves, a white bow tie, and a pocket handkerchief, also white. He would die in the First World War, pulverized by a shell.” This spartan use of language is lyrically engaging throughout his jaunty and often humorous recollections. However, on occasion it may leave the reader wanting more, as in this passage: “Like the gardener sprayed with his own hose in Lumière’s silent film, Inge Morath the photojournalist became a victim of the paparazzi when she married Arthur Miller. It was around then that I met her in New York, in December 1967, at that well-known headquarters for intellectual and artistic bohemians, the Chelsea Hotel.” The memory ends abruptly. Grenier leaves this rich, provocative beginning as a conclusion, moving along to his next vignette, a remembrance of an incident involving the surrealist poet Robert Desnos’ funerary urn and a timely quip by the surrealist poet Paul Eluard. His exploits at the landmark hotel receive no further investigations, though the setting and the time frame seem fecund for storytelling. In this instance, a less picaresque approach seems warranted.

A Box of Photographs brings to mind two other touchstone books with photography at their core, Susan Sontag’s On Photography and Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida, fda in that all three contain heartfelt, deeply personal, and astute observations of the medium. Grenier takes a more conversational tone in his writing, but like the other two authors, this too is an effort that bears repeated readings for the lovely prose and provocations it brings forth.