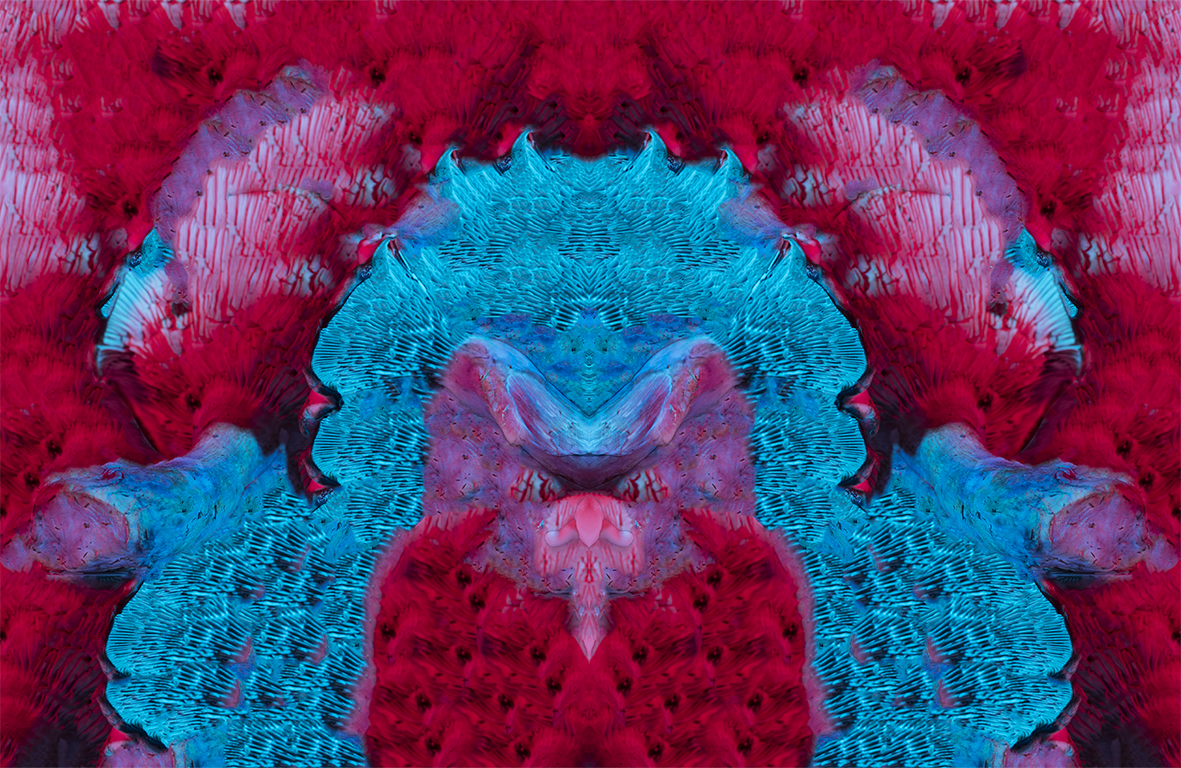

Artwork by contributor Julie Tixier.

For Issue 27, the editorial board of InVisible Culture is honored to present a special introduction by Dr. Jeffrey Tucker.

“Speculative Visions” is a title rich with denotative and connotative meanings covering the scope of this issue of (In)Visible Culture and of Cultural Studies more generally. It is a formulation that parallels “speculative fiction,” an umbrella term for writing that addresses any of a number of topics–augmentations of the human body, journeys through space and time, the wonder and warnings attached to technological developments, utopias and dystopias, alien encounters, and more; it also covers a range of genres–e.g. science fiction, fantasy, and horror–belonging to what the late Tzvetan Todorov called The Fantastic.1 It is in this latter sense particularly that such coverage is warranted; look closely at the content, production, or reception of “genre” literature or film and you will see boundaries a-blurring. Horror film director John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982) is based on the novella “Who Goes There?” (1938) by legendary science fiction editor and writer John W. Campbell, Jr. Pulp science fiction pioneer Hugo Gernsback was an influence on DC Comics impresario Julius Schwartz. And it is not unusual for science fiction fans to enjoy fantasy or horror; the genres often share creators and publishers or studios as well.

Despite valid usages of this sort, “speculative fiction” is often invoked to counter the stigma attached to science fiction and other paraliterary genres and media. In The Metamorphoses of Science Fiction (1979), Darko Suvin describes paraliterature as “the popular, ‘low,’ or plebeian literary production of various times, particularly since the Industrial Revolution.”2 As Suvin’s definition suggests, the speculative genres have often found expression in popular media, including mass media accessible to children and the lower and working classes, hence their sub-cultural status. This association has been furthered by matters of both production and content. In The Comic Book History of Comics (2012), writer Fred Van Lente and artist Ryan Dunlavey suggest that film is often considered “art” in part because auteur theory identifies “a personal, individual entity” behind its creation as with a painting or novel, whereas comics, which is really no more collaborative but is perhaps more conspicuously so, “cannot be art and (is) something lesser.”3 Scott McCloud makes a related observation in Understanding Comics (1993): “Traditional thinking has long held that truly great works of art and literature are only possible when the two are kept at arm’s length,” McCloud explains, “words and pictures together are considered, at best, a diversion for the masses, at worst a product of crass commercialism.”4

There are tradeoffs, however, to deploying “Speculative Fiction” to disarticulate its signified from stereotypes of mass-produced pulp culture and nerdy fanboys. For starters, the difference between science fiction and speculative fiction–or, for example, “graphic novel” and “comics”–often dissipates when fundamental matters of form, content, and technique are considered. Moreover, the histories specific to individual genres and media can get lost in the terminological shuffle. And in the 21st Century, there really should not be any need for this kind of fancy footwork. With seemingly constant developments in data science, telecommunications, and molecular biology (to name a few), our world is becoming more science fiction-like every day. Hollywood is flooding theaters with feature films of varying quality, presumably making someone a lot of money, based on original media in science fiction, fantasy, or superhero comics. When the most popular show on television is Game of Thrones and one of the most anticipated, or at least most hyped, films of this year is Blade Runner: 2049, it is clear that what was once nerdy is now cool (if only because the nerds are now in positions of power in the culture industry and/or have disposable income to spend on new iterations of content they enjoyed in the past). More to the point, for years now, scholars have been trained to interrogate the distinction between “high” and “low” culture and to understand that popular culture matters socially, politically, ideologically, economically. To paraphrase Terry Eagleton, the critical apparatuses applied to John Milton can also be applied to Bob Dylan5 (a fact not lost on last year’s Nobel Prize committee), or to bring it up-to-date, we need not be surprised to see allusions to Roland Barthes’s S/Z only pages away from allusions to Jay-Z. And these “speculative” fields are the sites of some of today’s most recent creative and critical work. “Afrofuturism,” for example, identifies science fiction and fantasy-related music (e.g. Sun Ra), writing (Octavia E. Butler), visual art (Wangechi Mutu), and more from across the histories of people of African descent. Science fiction and utopianism are at the heart of recent works by Marxist scholar Fredric Jameson: Archaeologies of the Future (2005) and An American Utopia (2016). Recent anthologies have highlighted inroads by women writers (Pamela Sargent’s Women of Wonder volumes (1995)), visual artists (Cathy Fenner and Lauren Panepinto’s 2015 volume of the same name), and feminist scholars (editor Marleen S. Barr’s Future Females (1981) and Afro-Future Females (2008)) have celebrated interventions into what had been a male-dominated field. Feminism encountered a vital corrective in the form of Donna Haraway’s “A Cyborg Manifesto” (1984), which demonstrated how both its titular metaphor and the cultural field from which it was borrowed are deconstructive and anti-“nature.” In a similar move, science fiction author and critic Samuel R. Delany notes that the paraliterary is that against which a normative category like “literature” defines itself: “Just as (discursively) homosexuality exists largely to delimit heterosexuality and to lend it a false sense of definition,” Delany explains, “paraliterature exists to delimit literature and provide it with an equally false sense of itself.”6 In short, any Humanities scholar who does not take the “speculative” seriously needs to take a second look.

And looking is what “Speculative Visions” is all about, not only in terms of how the pertinent objects of study are perceived, but also in terms of looking into–imagining, guessing at–the future, to “speculate” about what is to come. Delany identifies the future as a “paraspace,” where the rules of nature and/or those constructed by human beings do not necessarily apply.7 Whether near or far-off, the future is a popular setting for speculative visions, although other settings–the past, other planets, alternate realities–can also demonstrate how the putatively natural structures of the world with which we are familiar are often historically contingent conventions. For example, if hierarchical thinking is at least partly a result of our experience with gravity, what might happen if we left Earth for weightless and directionless outer space?8 This example suggests why Carl Freedman sees science fiction itself as a kind of critical theory.9 To “speculate” also means to take risks in order to make a profit, which prompts questions about who benefits from thinking so much about the future, or as Barbara Christian put it to black feminist scholars, “What do we think we’re doing anyway?”10 In whose interest do we produce such work, and toward what ends? These are questions that scholars should ask of themselves, and answer.

To do so requires looking into not only the future, but also the past, to engage with history, that of our nation, our fields, and our profession. That history is often “spectral,” embedded in the present, neither dead nor past. Science fiction author Nalo Hopkinson has noted that representations of futuristic space travel are shaped by histories of colonialism and expansionism.11 Gene Roddenberry, for example, imagined the original version of television’s Star Trek series as “a wagon train to the stars.” Moreover, the way the future was imagined in the early 20th Century, in terms of architecture and fashion as well as technology, differs from more recent visions. The designs of the Chrysler building and the Hoover Dam summoned the future, but 21st-century hotels and diners invoke art deco stylings for purposes of postmodern nostalgia. The future is not what it used to be.

“Speculative” also approximates “spectacle,” which suggests Guy DeBord’s analyses of mass media and commodity fetishism. In the Trump era, “the society of the spectacle” takes on additional meanings as the President barrages the public with demagoguery, atrocious behaviors, and headline-grabbing tweets that at times appear to be weaponized, designed to distract and exhaust any opposition. But we might choose instead to focus on the plural noun form, “spectacles,” as in corrective lenses. Delany has famously called science fiction “a significant distortion of the present that sets up a rich and complex dialogue with . . . (the) here and now.”12 Speculative visions, therefore, function as commentary on current issues by way of indirection or allegory. These lenses are “corrective” in the sense that they are a key step in the process of socio-political change: imagining what change, for good or for ill, would look like. For this reason, utopias and dystopias, in (para)literature, film, television, or other media–e.g. Metropolis, 1984, The Hunger Games, The Handmaid’s Tale–are newly-popular speculative modes. In 1967, Lyman Tower Sargent identified “The Three Faces of Utopianism,” which included (along with literature and the history of intentional communities) “utopian thought or philosophy.”13 Since Sargent’s inauguration of this interdisciplinary field, therefore, Utopian Studies has consistently engaged with critical theory, including anti-utopian thought deployed against fascism and violence (Theodor Adorno, Karl Popper) as well as utopianisms such as Ernst Bloch’s The Principle of Hope (1954, 1955, 1959), a psychological and hermeneutic principle14 for confronting our species’ numerous and often self-made challenges in the present and the future. This principle enables analysis and activism; it informs a refusal to accept things as they are and a belief that things can be better. Its combination with other workings of the spirit–sympathy, creativity, and the critical thinking common to scholarship in the Humanities–is necessary if our highest ideals are to be realized. The demonstration of such faculties in these contributions to (In)Visible Culture, and the cultivation of such amongst its readers, contribute to making this issue truly spectacular.

– Jeffrey Tucker, PhD. 2017

Issue 27: Speculative Visions

When the issue committee for Speculative Visions met for the first time, there was an excitement in the room as we attempted to craft a call that would be both specific and broad, inviting scholars, artists, and fans. We expected papers that centered on pop-culture media; we received that and so much more. In our call, we state that the last decade has seen a rise in popularity among science fiction, fantasy, and horror. These genres encourage the capacity to imagine post-human bodies, extraordinary worlds, techno-utopias, and claustrophobic spaces of violence. In their reliance upon the imagination, these speculative visions provide a space to consider contradictions and a carnivalesque interaction between popular culture and critical theory. The articles and artworks that constitute issue 27 defied our expectations in the best possible ways, forcing us to reconsider our own positions and investments as they shifted our understandings of the term “speculative.”

Scholar Jenn Cole turns our attention towards the horrors of the sacred in her analysis of the performance of the Eucharistic celebration in “Horrific Flesh, Holy Theater.” Read dramaturgically, the Eucharistic celebration pairs demonstration and invisibility in ways that embellish the aporetic, producing a theatre that demands total faith. The liturgical celebration of the Catholic communion in mass can be read against the demonstrative televangelical meeting or the certain proof of the Lanciano miracle, in which the communion elements transformed into “living” flesh and clotted blood, in that, while communion features a demonstrative assertion “This is my Body,” the demonstration itself, especially read theatrically, presents itself as a lack. The Eucharistic theatre features a play of absences and contrary “evidence,” profound distancing effects, which function as incitements to faith. In the Eucharistic rite, the leading actor fails to appear, the dramatic miracle fails to take place, and the dramaturgical framing exacerbates artifice rather than conceal it. The Eucharistic theatre is one in which all dramaturgical signs point one way and lead another, in a play of concealment and revelation, producing radical faith.

Cinematic speculations about the future of capitalism are the focus of Barbara Ferguson’s article, “The Branded Future: Brand-Placement Implications for Present Viewers and Future Narratives.” Drawing on film theory and recent studies of consumer behavior, as well as research into the methods of corporate product placement, Ferguson analyzes the appearances of contemporary brands like Lexus and Budweiser in speculative fiction films like Blade Runner, Minority Report, and Star Trek. These films’ future worlds suggest that, whatever humanity’s developments in travel, architecture, or fashion, we will nonetheless retain a recognizable market economy in which corporations continue to advertise their wares through visual, public displays. Ferguson argues that onscreen representations of commercialized futures implicate their audiences, and that every such representation, in essence, “safeguards the future for a political/economic system” very close to our current model. In perpetuating the mechanisms of the current market climate, Ferguson finds, visibly branded speculative futures reinforce brand constancy and endurance, crowding out other potentialities.

Drawing our attention to the intersection of feminist theory and the speculative, in “KillJoy’s Kastle: A Lesbian Feminist Haunted House,” independent curator and writer Genevieve Flavelle examines the collaborative installation and performance art experience produced by artists Allyson Mitchell and Deirdre Logue. KillJoy’s Kastle was first produced in fall 2013 in Toronto, and installed and performed for a second time in Los Angeles during October 2015. Modelled on Evangelical Christian Hell Houses that depict various scenes of sin intended to guide viewers toward the path of Christianity, KillJoy’s Kastle tours its viewers through a reanimation of lesbian feminist herstory intended to “pervert, not convert”. At once utopic and distopic KillJoy’s Kastle is a space in which “dead” theories, ideas, movements, and stereotypes are brought to back to life and problematized as riot ghouls, paranormal consciousness raisers, zombie folk singers, and ball busting dykes. Drawing on my first hand experience as a spectator and a performer in the LA iteration, I explore how KillJoy’s Kastle used negative feelings, direct audience engagement, and camp performance to create a carnivalesque space that provoked wide ranging responses to queer and feminist pasts and futures.

In ““Your Bad Theory Helped a Killer Go Free”: Recession Anxiety, Surveillance Labor, and Media Transition in Sinister,” John Roberts finds that within the genre of found-footage horror cinema, the viewer has typically been figured as a surveilling investigator who spectates and speculates on terrifying images. His essay explores how Sinister (Derrickson, 2013) incorporates these processes of speculative found footage surveillance within the film’s narrative diegesis. In doing so, the essay argues, Sinister effectively stages this forensic surveillance as labor within the context of the precarious post-recession U.S. economy, and articulates twin anxieties regarding economic recession and the securitizing function of surveillance as a dialetically interrelated pair of mutually co-constitutive forms of speculation. The essay argues that within the film, these two forms of speculation and the anxieties surrounding them are joined at the site of technological transition between analog and digital media, which the film figures as a hauntological specter of both the indexical photographic image and of monetary value. This in turn, the essay suggests, produces a new conceptual ground for theorizing about the form of speculation itself.

Daniel Grinberg brings the virtual to our attention in “A Tour of the Tactical Subjunctive: Virtually Visiting the Guantanamo Bay Museum of Art and History.” This article discusses Ian Alan Paul’s collaborative art project, the Guantanamo Bay Museum of Art and History, as a work that employs the tense of the ‘tactical subjunctive.’ By taking a ‘tour’ through this speculative museum space, I argue that its speculative mode can help visitors alternatively visualize the invisibilized sights of the Guantanamo Bay detention complex and circumvent the information suppression that constrains more representational modes. In addition, the Museum, which primarily exists as a website, enables a different mode of viewer engagement through its invocations of virtuality and imagination.

According to Anthony Vidler, the human subject is in the midst of a radical transformation from a modern, physical subject to a digital subject floating in cyber space. Patrick Brame’s “Ghosts are Real: Subjective Digitality within Analog Space in Crimson Peak” seeks to investigate this shift. To account for this subjective transformation and begin to describe it, he proposes we look towards cinema and the moving image. What can contemporary cinema’s nostalgic longing for a more analog aesthetic, i.e. a physical geography that holds a physical place in space, instead of utilizing a more digital one, i.e. a non-geography, a place without physicality, inform the spectator of their present condition? Indeed, if bodily humans are caught between modernism’s conception of space and the new cyberspace, a space where physicality is no longer necessary, what then, happens to film spectatorship? In order to unpack and explain the transformation of a modern, analog subject and spectator to a digital one he provides a close reading of Guillermo Del Toro’s latest film, Crimson Peak (2015). He begins by elaborating on Del Toro’s and his production designer, Thomas Sanders’s, very conscious design strategy and aesthetics for the film, specifically the primary setting: a gothic revival mansion. Del Toro’s emphasis on gothic tropes and materially realistic aesthetics presents the spectator with several representations of Sigmund Freud’s uncanny, specifically inorganic animation and doubling. It is within the gothic revival mansion that the spectator is made aware of their fractured spectatorship: caught between a physical, materialistic mode of spectating and a digital one. He then highlights the spectator’s confused positionality within, he argues, a monstrous feminine space inhabited by crimson red ghosts that mirror the fractured and unanchored experience of contemporary film spectatorship.

In “The Utopian Failure of Constant’s New Babylon” scholars Darren Jorgenson and Laetitia Wilson reconsider Constant Nieuwenhuys’ New Babylon and Situationism, urbanism and utopia. According to Jorgenson and Wilson, for nearly twenty years, Constant Nieuwenhuys proposed a revolutionary vision of a new world and a whole new way of life. In the near future, automation would free human life to dedicate itself to collectivity and play. New Babylon was the architectural form of this freedom, a series of interconnected platforms that would host different environments for living. Today, the remains of this long-abandoned project are stored in museums and exhibited in galleries. As relics, they suggest a doubled sensibility. They are a part of the utopian project of the 1960s, and also symbolize the failure of this decade to realise utopia. The legacy of New Babylon lies not in social change, but as with the avant-gardes themselves, in an ongoing scholarship that surround their creations and propositions.

The artwork of Darrell Black introduce us to “definism” which portrays various differences in human nature, from life’s everyday dramas to humankind’s quest to under-standing self. The main focus of the artworks, is transporting viewers from the doldrums of their daily reality, to a visual world where images coexist in an alternate reality that everyone in contact with the artwork can interact through touch while simultaneously interpreting and understanding with one’s own power of imagination.

Julie Tixier pulls us into the world of posthumanism in her collection “Extraordinary Conceptions.” This 2016 collection looks at the current genetic modifications on embryos and imagines the future cross-breed new species of laboratories. The relations and boundaries between species are becoming increasingly blurred with the advances of biotechnologies. The current research enables the transfer of genetic material from one species to an other, from animal to human. However, scientists know these practices might slip out of their control and that it is possible to pass down genetic modifications to posterity and even to provoke the emergence of a new species. Genes are composed of informations, interact in complex ways and have multiple functions. Consequently, if we alter their informations, some unexpected secondary effects might be produced, like the emergence of chimeras with multiple genomes.As the perspectives offered question the borders of our human species, ‘Extraordinary Conceptions’ tries to transgress the borders of the imaginary and the representation of human nature. The series builds up a world between fascination and disgust which confronts us to a new language with unexpected structures, asking us which DNA might have been involved. It suggests that if we go beyond the limits, we risk to fall into a world which lacks of coherence.

Scholars Adam Fish, Bradley Garrett, and Oliver Case’s video project “Extended Flight: The Emergence of Drone Sovereignty” considers how concepts of technological autonomy and sovereignty circulate around unmanned aerial vehicles or drones. On the one hand, techno-utopians see drones as autonomous agents capable of extending and liberating the human sensory experience – most importantly sight – into the atmosphere. Conversely, techno-dystopians frame drones as sovereign killing and surveillance robots. This essay interrogates an experiment piloting a drone in southwest Iceland to collect video of artefacts surrounding undersea fibre-optic cables and cable stations. They had an experience wherein the drone usurped its autonomous connection to us as pilots and appeared to be temporarily sovereign. This field experiment complicates the binary outlined above, challenging the one-dimensional interpretations of drone. In their framing, the drone simultaneously extends human senses while informing a dread about technological sovereignty. In conclusion, they speculate on the problems and potentials of sovereignty and autonomy in networked assemblages and consider a situation where the human agent becomes potentially redundant.

And finally, “Pro-Found Objects: The Magick of the Mundane,” by Michael E. Stephen, a visual artist that primarily works in the expanded field of sculpture, considers our affective response towards nostalgia, especially through the mediation of film, and how specifically the genre of Horror can transcend the liminal space of the screen and activate the objects of our daily lives.

- Tzvetan Todorov, The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to a Literary Genre, (Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1975). ↩

- Darko Suvin, The Metamorphoses of Science Fiction, (New Haven: Yale UP, 1979) vii. ↩

- Fred Van Lente and Ryan Dunlavey, The Comic Book History of Comics, (San Diego: IDW, 2012) 109. ↩

- Scott McCloud, Understanding Comics (Northampton, MA: Tundra, 1993)140. ↩

- Terry Eagleton, Literary Theory (Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1983) 205. ↩

- Samuel R. Delany, “The Para • doxa Interview,” 1995, Shorter Views (Hanover: Wesleyan UP, 1999) 205. ↩

- Samuel R. Delany, “Some Real Mothers . . . .” Silent Interviews (Hanover: Wesleyan UP, 1994) 169, 168. ↩

- Samuel R. Delany with Howard Chaykin, Empire (New York: Berkley, 1978) 2. ↩

- See Carl Freedman, Critical Theory and Science Fiction (Wesleyan, UP 2000). ↩

- Barbara Christian, “But What Do We Think We Are Doing Anyway: The State of Black Feminist Criticism(s) or My Version of a Little Bit of History,” 1989, Within the Circle: An Anthology of African American Literary Criticism from the Harlem Renaissance to the Present, ed. Angelynn Mitchell (Durham: Duke UP, 1994) 499. ↩

- Nalo Hopkinson, Introduction, So Long Been Dreaming: Postcolonial Science Fiction and Fantasy, ed. Nalo Hopkinson and Uppinder Mehan (Vancouver: Arsenal, 2004) 8. See also John Rieder’s Colonialism and the Emergence of Science Fiction (Wesleyan UP, 2008). ↩

- Samuel R. Delany, “Dichtung und Science Fiction,” Starboard Wine (Pleasantville, NY: Dragon Press, 1984) 176 ↩

- Lyman Tower Sargent, “The Three Faces of Utopianism,” minnesota review 7.3 (1967): 222-230. ↩

- Carl Freedman, “Science Fiction and Utopia: A Historico-Philosophical Overview,” Learning from Other Worlds: Estrangement, Cognition, and the Politics of Science Fiction and Utopia, ed. Patrick Parrinder (Durham: Duke UP, 2001) 72-97. ↩